The History of the Ballpoint Pen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballpoint Basics 2017, Ballpoint Pen with Watercolor Wash, 3 X 10

Getting the most out of drawing media MATERIAL WORLD BY SHERRY CAMHY Israel Sketch From Bus by Angela Barbalance, Ballpoint Basics 2017, ballpoint pen with watercolor wash, 3 x 10. allpoint pens may have been in- vented for writing, but why not draw with them? These days, more and more artists are decid- Odyssey’s Cyclops by Charles Winthrop ing to do so. Norton, 2014, ballpoint BBallpoint is a fairly young medium, pen, 19½ x 16. dating back only to the 1880s, when John J. Loud, an American tanner, Ballpoint pens offer some serious patented a crude pen with a rotat- advantages to artists who work with ing ball at its tip that could only make them. To start, many artists and collec- marks on rough surfaces such as tors disagree entirely with Koschatzky’s leather. Some 50 years later László disparaging view of ballpoint’s line, Bíró, a Hungarian journalist, improved finding the consistent width and tone Loud’s invention using quick-drying of ballpoint lines to be aesthetically newspaper ink and a better ball at pleasing. Ballpoint drawings can be its tip. When held perpendicular to composed of dense dashes, slow con- its surface, Bíró’s pen could write tour lines, crosshatches or rambling smoothly on paper. In the 1950s the scribbles. Placing marks adjacent to one Frenchman Baron Marcel Bich pur- another can create carefully modu- chased Bíró’s patent and devised a lated areas of tone. And if you desire leak-proof capillary tube to hold the some variation in line width, you can ink, and the Bic Cristal pen was born. -

19Th Century Writing Activity: Pen &

Lesson Plan: #NoyesArtatHome 19th Century Writing Activity: Pen & Ink Activity based on letters on display in the Noyes Museum’s Estell Empire Exhibition For ages 12 & up Experience with cursive* writing not necessary Assistance from an adult would be helpful. Overview: Round Hand Script: This was the dominant cursive* writing style among 19th century writing “masters,” whose An account book from John Estell’s general store models were engraved on metal. Letters Circa 1836 – 1837 sloped to the right, and thick lines were © Collection of Stockton University produced on the downstrokes using a flexible, straight-edged (not pointed) pen nib (tip). Thin lines were made by using the corner of the nib. Round hand included decorative swirls referred to as “command of hand.” Copperplate: This type of writing was made with a flexible, pointed metal pen. Copperplate script differs from round hand in the gradual swelling of the broad strokes on curved forms and the narrowness of the backstrokes of b, e, and o. Definitions from Britannica.com: https://www.britannica.com/topic/black-letter Project Description: This lesson provides a brief overview of handwriting in the 19th century and a hands-on writing activity. First, paint with a teabag to make “old” looking paper. To write, use a quill** pen with black ink or watered-down paint, or a marker. Try to read and copy the example of 19th century writing. Can you write your own name, or a whole letter to a friend? Supplies: 8.5 x 11” piece of paper A tea bag; preferably a darker tea such as black tea (Lipton, Red Rose) A watercolor brush Your choice of: a quill** pen and black ink, watered-down black paint with a fine-tipped brush, or a black marker (for example: Crayola – “broad line” or Sharpie – “fine point,” the newer, the better) *Cursive writing is a style of writing in which all of the letters in a word are connected. -

Writing Instruments 1.800.877.8908 93

92 Russell-Hampton Company WRITING INSTRUMENTS www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Waterman Pens Detail 92 Russell-Hampton Company www.ruh.com 1.800.877.8908 93 Serving Rotarians Since 1920 A. R66032 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Features include: newly designed teardrop clip & inlaid feather band, high gloss black lacquer cap, gold accents, fine-point black Roller Ball refill, with full-color slant top Rotary International logo, & handsome display box. Lifetime guarantee. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $32.95 ea. • Buy 6 $30.95 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.95 ea. B. R66040 Quill® Heritage Roller Ball Pen Elegant teardrop clip and inlaid feather band highlight this beautiful brushed chrome, smooth writing Quill® rollerball pen. Rotary International emblem in crown. Lifetime guarantee. Gift Boxed. Unit Price $34.95 • Buy 3 $33.20 ea. • Buy 6 $31.45 ea. • Buy 12+ $29.70 ea. C. R66012 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Pen & Pencil Set • Classic high gloss black lacquer finish complimented with 23.3-karat gold electroplated clip & trim. Die-struck Rotary emblems affixed to the crowns. Ball pen is fitted with a black ink, medium point refill. Pencil is fitted with 0.5mm lead. Waterman Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $107.95 • Buy 2 $102.50 ea. • Buy 3+ $97.25 ea. D. R66011 Waterman® Hemisphere Black Ball Pen • Same ball pen as sold in above set. Water- man Signature Presentation Blue Box with satin lining. Unit Price $51.95 • Buy 3 $49.35 ea. • Buy 6 $46.85 ea. • Buy 12+ $44.55 ea. -

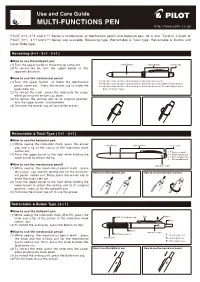

Multi-Functions Pen

Use and Care Guide MULTI-FUNCTIONS PEN http://www.pilot.co.jp/ PILOT 2+1, 3+1 and 4+1 Series-a combination of mechanical pencil and ballpoint pen, all in one. Total of 4 kinds of PILOT 2+1, 3+1 and 4+1 Series are available : Revolving type, Retractable & Twist type, Retractable & Button and Lever Slide type. Revolving (4 +1 . 3 +1 . 2 +1 ) ●How to use the ballpoint pen (1) Turn the upper barrel to make the tip come out. Lower Barrel Upper Barrel Eraser Cap (2) To retract the tip, turn the upper barrel to the opposite direction. ●How to use the mechanical pencil (1) Turn the upper barrel to make the mechanical 2+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen & Red ink ballpoint pen) 3+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen, Red ink ballpoint pen & Blue ink ballpoint pen) pencil come out. Press the eraser cap to make the 4+1 (Mechanical pencil, Black ink ballpoint pen, Red ink ballpoint pen, Blue ink ballpoint pen & lead come out. Green ink ballpoint pen) (2) To retract the lead , press the lead onto the paper while pushing the eraser cap down. (3) To retract the writing unit to its original position, turn the upper barrel anticlockwise. (4) Unscrew the eraser cap off to use the eraser. Retractable & Twist Type ( 3 +1 . 2 +1) ●How to use the ballpoint pen (1) While seeing the indication mark, press the eraser Lower Barrel Upper Barrel Eraser Cap cap and a tip of the colour of the indication mark 0.5 comes out. -

Quill Pen and Nut Ink

Children of Early Appalachia Quill Pen and Nut Ink Grades 3 and up Early writing tools were made from materials people could find or easily make themselves. Children used a slate with chalk and stone to write lessons at schools. They also practiced drawing and writing with a stick in dirt. Penny pencils for slates were available at general stores. Paper was purchased at stores too. Before the invention of pencils and pens, children used carved twigs or goose-quill pens made by the teacher. Ink was made at home from various ingredients (berries, nuts, roots, and soot) and brought to school. Good penmanship was highly valued but difficult to attain. Objective: Students will make pen and ink from natural materials and try writing with these old- fashioned tools. Materials: Pen: feathers, sharp scissors or a pen knife (Peacock or pheasant feathers make wonderful pens, but any large feather from a goose or turkey works well too.) Ink: 10 walnut shells, water, vinegar, salt, hammer, old cloth, saucepan, small jar with lid, strainer. (After using the homemade ink, students make like to continue practicing writing with the quill, so you may want to provide a bottle of manufactured ink for further quill writings.) Plan: Pen: Cut off the end of the feather at a slant. Then cut a narrow slit at the point of the pen. Ink: 1. Crush the shells in cloth with a hammer. 2. Put shells in saucepan with 1 cup of water. Bring to a boil, and then simmer for 45 minutes or until dark brown. -

Pitt Artist Pen Calligraphy !

Pitt Artist Pen Calligraphy ! A new forest project in Colombia secures the livelihoods of small farmers and the Faber-Castell stands for quality wood supply for Faber-Castell – a unique environment protection programme, Founded in 1761, Faber-Castell is one of the world’s oldest industrial companies and is now in certified by the UN. the hands of the eighth generation of the same family. Today it is represented in more than With a socially exemplary and sustainable reforestation project in Colombia, Faber-Castell con- 120 countries. Faber-Castell has its own production sites in nine countries and sales companies tinues to reinforce its leading role as a climate-neutral company. On almost 2,000 hectares of in 23 countries worldwide. Faber-Castell is the world’s leading manufacturer of wood-cased pencils, grassland along the Rio Magdalena in Colombia, small farmers are planting tree seedlings for fu- producing over 2000 million black-lead and colour pencils per year. Its leading position on the ture pencil production. The fast-growing forests not only provide excellent erosion protection for international market is due to its traditional commitment to the highest quality and also the large this region plagued by overgrazing and flooding, they are also a reliable source of income for the number of product innovations. farmers living in modest circumstances, who are paid for forest maintenance and benefit from the Its Art & Graphic range allows Faber-Castell to enjoy a great reputation among artists and hobby proceeds from the timber. The environmental project was one of the first in the world to be certi- painters. -

The Origins of the Musical Staff

The Origins of the Musical Staff John Haines For Michel Huglo, master and friend Who can blame music historians for frequently claiming that Guido of Arezzo invented the musical staff? Given the medieval period’s unma- nageable length, it must often be reduced to as streamlined a shape as possible, with some select significant heroes along the way to push ahead the plot of musical progress: Gregory invented chant; the trouba- dours, vernacular song; Leoninus and Perotinus, polyphony; Franco of Cologne, measured notation. And Guido invented the staff. To be sure, not all historians put it quite this way. Some, such as Richard Hoppin, write more cautiously that “the completion of the four-line staff ...is generally credited to Guido d’Arezzo,”1 or, in the words of the New Grove Dictionary of Music, that Guido “is remembered today for his development of a system of precise pitch notation through lines and spaces.”2 Such occasional caution aside, however, the legend of Guido as inventor of the staff abides and pervades. In his Notation of Polyphonic Music, Willi Apel writes of “the staff, that ingenious invention of Guido of Arezzo.”3 As Claude Palisca puts it in his biography of Guido, it was that medieval Italian music writer’s prologue to his antiphoner around 1030 that contained one of the “brilliant proposals that launched the Guido legend, the device of staff notation.”4 “Guido’s introduction of a system of four lines and four spaces” is, in Paul Henry Lang’s widely read history, an “achievement” deemed “one of the most significant in -

Penmanship Activity Pack

A Day in a One-Room Schoolhouse Marathon County Historical Society Living History Learning Project Penmanship Lesson Activity Packet For Virtual Visits Project Coordinators: Anna Chilsen Straub & Sandy Block Mary Forer: Executive Director (Rev. 6/2020) Note to Participants This packet contains information students can use to prepare for an off-site experience of a one-room school. They may be used by classroom teachers to approximate the experience without traveling to the Little Red Schoolhouse. They are available here for students who might be unable to attend in person for any reason. In addition, these materials may be used by anyone interested in remembering or exploring educational experiences from more than a century ago. The usual lessons at the Little Red Schoolhouse in Marathon Park are taught by retired local school teachers and employees of the Marathon County Historical Society in Wausau, Wisconsin. A full set of lessons has been video-recorded and posted to our YouTube channel, which you can access along with PDFs of accompanying materials through the Little Red Schoolhouse page on our website. These PDFs may be printed for personal or classroom educational purposes only. If you have any questions, please call the Marathon County Historical Society office at 715-842-5750 and leave a message for Anna or Sandy, or email Sandy at [email protected]. On-Site Schoolhouse Daily Schedule 9:00 am Arrival Time. If you attended the Schoolhouse in person, the teacher would ring the bell to signal children to line up in two lines, boys and girls, in front of the door. -

Handwriting Today . . . and a Stolen American Relic

Reviews Handwriting Today... and A Stolen American Relic WILLIAM BUTTS FLOREY, Kitty Burns. Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwriting. Brooklyn: Melville House Publishing, 2009. 8vo. Hardbound, dust jacket. 190pp. Illustrations. $22.95. HOWARD, David. Lost Rights: The Misadventures of a Stolen Ameri- can Relic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010. Small 4to. Hardbound, dust jacket. 344pp. $26.00. If you’re anything like me, handling handwriting from many eras on a daily basis, you get sick and tired of the endless refrain from the general public when viewing old documents: “People all had such beautiful handwriting back then!” or, conversely, “No one writes like that today!” Et cetera—ad nauseum. I’ve almost given up refuting these gross generalizations, but “in the old days” I’d pull out letters from, say, Horace Greeley, the Duke of Wellington, a Civil War soldier and other notori- ously illegible scribblers to prove that every age has its share of beautiful penmanship, horrid penmanship and mediocre pen- manship. And as for modern penmanship, most of the examples of current penmanship I see are in the form of personal checks MANUSCRIPTS, VOL. 62 235 NO. 3, SUMMER 2010 236 MANUSCRIPTS (thankfully), and there too I find a mix of beautiful, horrid and mediocre penmanship. The more things change, the more they you-know-what. Which is one beef I have with Kitty Burns Florey in her oth- erwise enjoyable Script and Scribble: The Rise and Fall of Handwrit- ing. Other than the uninitiated general public cited above, the other group that unfairly bemoans current penmanship are the handwriting snobs (which I don’t consider Florey)—elit- ists whose devotion to pseudo-Palmerian calligraphy or other esoteric specialties blinds them to the simple, honest, unsophis- ticated attractiveness of the day-to-day script of ordinary persons who’ve never studied calligraphy. -

Making a Quill Pen This Activity May Need a Little Bit of Support However the End Project Will Be Great for Future Historic Events and Other Crafting Activities

Making A Quill Pen This activity may need a little bit of support however the end project will be great for future historic events and other crafting activities. Ask your maintenance person to get involved by providing the pliers and supporting with the production of the Quill Pen. What to do 1. Use needle-nose pliers to cut about 1" off of the pointed end of the turkey feather. 2. Use the pliers to pluck feathers from the quill as shown in the first photo on the next page. Leave about 6" of feathers at the top of the quill. 3. Sand the exposed quill with an emery board to remove flaky fibres and unwanted texture. Smoothing the quill will make it more pleasant to hold while writing. 4. If the clipped end of the quill is jagged and/or split, carefully even it out using nail scissors as shown in the middle photo. 5. Use standard scissors to make a slanted 1/2" cut on the tip of the quill as shown in the last photo below. You Will Need 10" –12" faux turkey feather Water -based ink 6. Use tweezers to clean out any debris left in the hollow of the quill. Needle -nose pliers 7. Cut a 1/2" vertical slit on the long side of the quill tip. When the Emery board pen is pressed down, the “prongs” should spread apart slightly as Nail scissors shown in the centre photo below. Tweezers Scissors Keeping it Easy Attach a ball point pen to the feather using electrical tape. -

Pen and Ink 3 Required Materials

Course: Pen and Ink 3 Required materials: 1. Basic drawing materials for preparatory drawing: • A few pencils (2H, H, B), eraser, pencil sharpener 2. Ink: • Winsor & Newton black Indian ink (with a spider man graphic on the package) This ink is shiny, truly black, and waterproof. Do not buy ‘calligraphy ink’. 3. Pen nibs & Pen holders : Pen nibs are extremely confusing to order online, and packages at stores have other nibs which are not used in class. Therefore, instructor will bring two of each nib and 1nib holders for each number, so students can buy them in the first class. Registrants need to inform the instructor if they wish to buy it in the class. • Hunt (Speedball) #512 Standard point dip pen and pen holder • Hunt (Speedball) # 102 Crow quill dip pen • Hunt (Speedball) # 107 Stiff Hawk Crow quill nib 4. Paper: • Strathmore Bristol Board, Plate, 140Lb (2-ply), (Make sure it is Plate surface- No vellum surface!) Pad seen this website is convenient: http://www.dickblick.com/products/strathmore-500-series-bristol-pads/ One or two sheets will be needed for each class. • Bienfang 360 Graphic Marker for preparatory drawing and tracing. Similar size with Bristol Board recommended http://www.dickblick.com/products/bienfang-graphics-360-marker-paper/ 5. Others: • Drawing board: Any board that can firmly hold drawing paper (A tip: two identical light weight foam boards serve perfectly as a drawing board, and keep paper safely in between while traveling.) * Specimen holder (frog pin holder, a small jar, etc.), a small water jar for washing pen nib) • Divider, ruler, a role of paper towel For questions, email Heeyoung at [email protected] or call 847-903-7348. -

2021 Premium Business Gifts Advertise with Lamy

2021 Premium Business Gifts Advertise with Lamy Fountain pens Ballpoint pens Rollerball pens Mechanical pencils Multisystem pens Notebooks Set offers Lamy’s wide range of promotional articles is available solely to commercial enterprises, businesses and Contents freelancers. Private sale is not possible. Sending a lasting message ................... 3 LAMY AL-star EMR ......................... 44 Taking responsibility – shaping the future ....... 4 LAMY twin pen ............................. 46 From Heidelberg into the world ............... 8 LAMY tri pen ............................... 48 LAMY safari . 10 Notebook assortment from Lamy ............. 50 LAMY AL-star .............................. 12 Sets ....................................... 54 LAMY xevo ................................ 14 Cases ..................................... 55 LAMY noto ................................ 16 LAMY ideos ............................... 56 LAMY logo ................................ 18 LAMY studio ............................... 58 LAMY tipo ................................. 28 LAMY scala. 60 LAMY econ ................................ 30 LAMY 2000 ................................ 62 LAMY pur .................................. 32 LAMY 2000 M ............................. 64 LAMY swift ................................ 34 LAMY dialog cc ............................ 66 LAMY cp1 ................................. 36 LAMY dialog .............................. 68 LAMY pico ................................ 38 LAMY imporium ............................ 70 LAMY