Taylor, Michael a (2015) Rediscovery of an Ichthyosaurus Breviceps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

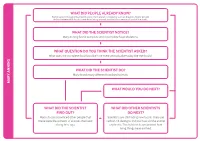

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

JOHN HUNTER: SURGEON and NATURALIST* by DOUGLAS GUTHRIE, M.D., F.R.C.S.Ed

JOHN HUNTER: SURGEON AND NATURALIST* By DOUGLAS GUTHRIE, M.D., F.R.C.S.Ed. " " Why Think ? Why not try the Experiment ? Professor John Chiene,*^ whose apt maxims of surgical practice still ring in the ears of those of us who were fortunate to be his pupils, was wont to advise us to avoid becoming mere " hewers of wood and drawers of water." Such counsel would have delighted John Hunter who, with a vision far ahead of his time, laboured to prevent surgery from becoming an affair of carpentry and plumbing. In the present era of specialism and super-specialism it is indeed salutary to recall this great figure of medical history, and although the work of John Hunter has been the theme of a dozen biographers and nearly a hundred Hunterian Orators, the remarkable story remains of perennial interest. Parentage and Youth John Hunter, the youngest of a family of ten children, was born on 14th February 1728, at the farm of Long Calderwood, some seven miles south-east of Glasgow. His father, already an old man, died when John was ten years old, and he remained in the care of an indulgent mother and appears to have been a " spoiled child." It is indeed remarkable that such a genius, at the age of seventeen, could neither read nor write. But, as is well known, the brilliant schoolboy does not always fulfil the promise of early years, and, conversely, the boy who has no inclination for scholarship may grow to be a clever man. John Hunter was one who blossomed late ; nevertheless his education did progress, although along unusual lines, for in " his own words he wanted to know all about the clouds and the grasses, and why the leaves changed colour in autumn : I watched the ants, bees, birds, tadpoles and caddisworms ; I pestered people with questions about what nobody knew or cared anything about." His sister Janet, eldest of the surviving children, had married a Mr Buchanan, a Glasgow cabinet- maker. -

Nature [February 11, 1928

210 NATURE [FEBRUARY 11, 1928 The Bicentenary of John Hunter. By Sir ARTHUR KEITH, F.R.S. ONSIDER for a moment the unenviable position to buy Hunter's museum for £15,000. The collec C.) of John Hunter's two executors in the year tion was handed over to the Corporation of Surgeons 1793-his nephew Dr. Matthew Baillie and his in 1800; that body obtained at the same time a young brother-in-law, Mr. (later Sir) Everard Home. new charter, became the College of Surgeons, and Hunter's sudden death on Oct. 16, 1793, in his established itself and its museum on the south side sixty-sixth year, left, on their hands a huge estab of Lincoln's Inn Fields-where both still flourish. lishment running The two ex from Leicester ecutors continued Square to Charing to believe in Cross Road-just Hunter's great to the south of ness, as may be the site now oc seen from the fol cupied by the lowing quotation Alhambra Music taken from the Hall. The income issue of the Col of the establish lege calendar for ment had sud the present year : denly ceased; a "In the year sum of more than 1813, Dr. Matthew £10,000 a year was Baillie and Sir needed to keep it Eve rard Home, going. A brief Bart., executors of search showed John Hunter, 'be them that the place ing desirous of was in debt ; bills showing a lasting mark of respect ' to had to be met. the memory of the Hunter's carriage late Mr. -

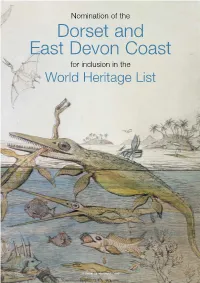

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

the Papers Philosophical Transactions

ABSTRACTS / OF THE PAPERS PRINTED IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, From 1800 to1830 inclusive. VOL. I. 1800 to 1814. PRINTED, BY ORDER OF THE PRESIDENT AND COUNCIL, From the Journal Book of the Society. LONDON: PRINTED BY RICHARD TAYLOR, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. CONTENTS. VOL. I 1800. The Croonian Lecture. On the Structure and Uses of the Meinbrana Tympani of the Ear. By Everard Home, Esq. F.R.S. ................page 1 On the Method of determining, from the real Probabilities of Life, the Values of Contingent Reversions in which three Lives are involved in the Survivorship. By William Morgan, Esq. F.R.S.................... 4 Abstract of a Register of the Barometer, Thermometer, and Rain, at Lyndon, in Rutland, for the year 1798. By Thomas Barker, Esq.... 5 n the Power of penetrating into Space by Telescopes; with a com parative Determination of the Extent of that Power in natural Vision, and in Telescopes of various Sizes and Constructions ; illustrated by select Observations. By William Herschel, LL.D. F.R.S......... 5 A second Appendix to the improved Solution of a Problem in physical Astronomy, inserted in the Philosophical Transactions for the Year 1798, containing some further Remarks, and improved Formulae for computing the Coefficients A and B ; by which the arithmetical Work is considerably shortened and facilitated. By the Rev. John Hellins, B.D. F.R.S. .......................................... .................................. 7 Account of a Peculiarity in the Distribution of the Arteries sent to the ‘ Limbs of slow-moving Animals; together with some other similar Facts. In a Letter from Mr. -

Thomas Colby's Book Collection

12 Thomas Colby’s book collection Bill Hines Amongst the special collections held by Aberystwyth University Library are some 140 volumes from the library of Thomas Colby, one time Director of the Ordnance Survey, who was responsible for much of the initial survey work in Scotland and Ireland. Although the collection is fairly small, it nonetheless provides a fascinating insight into the working practices of the man, and also demonstrates the regard in which he was held by his contemporaries, many of them being eminent scientists and engineers of the day. Thomas Colby was born in 1784, the son of an officer in the Royal Marines. He was brought up by his aunts in Pembrokeshire and later attended the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, becoming a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in December 1801.1 He came to the notice of Major William Mudge, the then Director of the Ordnance Survey, and was engaged on survey work in the south of England. In 1804 he suffered a bad accident from the bursting of a loaded pistol and lost his left hand. However, this did not affect his surveying activity and he became chief executive officer of the Survey in 1809 when Mudge was appointed as Lieutenant Governor at Woolwich. During the next decade he was responsible for extensive surveying work in Scotland and was also involved in troublesome collaboration with French colleagues after the end of the Napoleonic Wars, connecting up the meridian arcs of British and French surveys. Colby was made head of the Ordnance Survey in 1820, after the death of Mudge, and became a Fellow of the Royal Society in the same year. -

A Memoir of William and John Hunter

time and the bodies were dissected, or “an anatomy was held” in a hall crowded with eager witnesses, by a demonstrator, the students having no chance to do any practical dissection with their own hands. In 1752 an act was passed providing for the dissection of the bodies of all persons executed for murder in Great Britain. The ostensible purpose of the Act was to make the penalty of homicide more infamous and similarly, in order to diminish the increasing prevalence of burglary and highway robbery, then still punishable with death, a Bill was introduced into the House of Commons in 1796, providing that the bodies of persons executed for those crimes should also be handed over for dissection. But, on the ground that it annihilated the difference between murder and the lesser forms of crime (though the older grants had failed to recognize any such difference) the Bill failed to secure acceptance. It was not until 1832 that the so-called Warburton Anatomy Act was passed providing a legal way in which an ample supply of anatom- ical material could be secured by all reputable schools and teachers. Peachey gives a list of the private teachers of anatomy in England between 1700 and 1746 with some account of their activities. It is inter- esting to Americans to find Dr. Abraham A Memoir of Will iam and John Hunt er : By Chovet among those mentioned, because he George C. Peachey, William Brendon and Son, came to this country and attained a distin- Plymouth, G. B., 1924. guished place in the profession in Philadelphia. -

JOHN HUNTER AS a GEOLOGIST Lecture Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England on 10Th December, 1952 by F

JOHN HUNTER AS A GEOLOGIST Lecture delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England on 10th December, 1952 by F. Wood Jones, F.R.S., F.R.C.S. MORE THAN A DOZEN full-length biographies of John Hunter have been published; over eighty Hunterian Orations have been delivered in this College and a Society to perpetuate his memory has been in existence for more than a hundred and thirty years. Hunter has been lauded as a surgeon, as a comparative anatomist and as a physiologist. Full tribute has been paid to his skill as an experimenter and to his industry and discrimination in building up his vast collection of specimens. But with all this outpouring of genuine appreciation of his great attainments, John Hunter remains practically unknown as a pioneer in the study of geology and paleontology. No mention is made of Hunter, or his contribution to geological knowledge, in any of the standard works dealing with the history of geology and paleontology. Starting with the great work of Karl Alfred Von Zittel, published in 1899, and until the recent monograph by Charles Coulston Gillespie in 1951, we seek in vain for any reference to the man or to his work on paleontology. It is perhaps more remarkable that his contributions to geological science are not mentioned by Dr. R. G. Willis in his paper on " The Contributions of British Medical Men to the foundations of Geology," published in 1834. In this review, Willis gives a full account of the work of James Parkinson (1755-1824) whose three monumental volumes entitled " Organic Remains of a Former World" were published from 1804 to 1811. -

Priorities in Scientific Discovery: a Chapter in the Sociology of Science Author(S): Robert K

Priorities in Scientific Discovery: A Chapter in the Sociology of Science Author(s): Robert K. Merton Reviewed work(s): Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 22, No. 6 (Dec., 1957), pp. 635-659 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2089193 . Accessed: 10/11/2012 19:21 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Sociological Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.224 on Sat, 10 Nov 2012 19:21:07 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions American SOCIOLOGICAL December Volume 22 1957 Review Number 6 OfficialJournal of the AmericanSociological Society PRIORITIES IN SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY: A CHAPTER IN THE SOCIOLOGY OF SCIENCE * ROBERT K. MERTON Columbia University W E can only guess what historians of the A Calendar of Disputes over Priority. We future will say about the condition of begin by noting the great frequency with present-day sociology. But it seems which the history of science is punctuated by safe to anticipate one of their observations. -

John Hunter's Letters by WILLIAM RICHARD LEFANU, Librarian, Royal College of Surgeons of England, London W.C.2

John Hunter's Letters By WILLIAM RICHARD LEFANU, Librarian, Royal College of Surgeons of England, London W.C.2 N EVER ask me what I have said or what I have written, but if you will ask me what my present opinions are, I will tell you," John Hunter once said to a pupil. Some of Hunter's 'present opinions,' the current thoughts which he wrote down with no inten- tion of publishing, can still be read in his letters. But his letters have to be looked for in a number of biographies and other books. When Hunter died in October 1793 he had published only a frac- tion of his work. One book which was ready for publication, A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation, and Gun-sbot Wounds, was edited the next year by Everard Home, the brother-in-law who for nine years had been his private assistant. It is well-known that Home kept Hunter's other manuscripts for thirty years and then burnt them in 1823. The little that Home allowed to survive was garnered by William Clift and Rich- ard Owen and published piecemeal between 1830 and 1861, chiefly in the Catalogues of the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons. Besides these papers of his own, many of Hunter's pupils had kept notes of his lectures, from which two versions of the Lec- tures on Surgery were published in 1833 and 1835. About the same time Hunter's letters began to be generally known. For the last twenty years of his life Hunter corresponded regularly with Edward Jenner, his favourite pupil, who had gone back to a country practice in Gloucestershire, and was not brought to London again by his discovery of vaccination till several years after Hunter's death. -

(1991) 17 Faraday's Election to the Royal Society

ll. t. Ch. ( 17 References and Notes ntbl pnt n th lhtt dplnt ll th prtl thr t rd fr r pprh 0. It hld b phzd tht, fr 1. H. n n, The Life and Letters of Faraday, 2 l,, vh, th t r fndntl prtl nd tht hl nn, Grn C,, ndn, 86, t r pnd f th h plx pttrn f fr 2. , ndll, Faraday as a Discoverer, nn, Grn ld b d t nt fr "ltv ffnt" nd fr th rlrt C., ndn, 868, f rtl. , Gldtn, Michael Faraday, Mlln, ndn, . A, Faraday as a Natural Philosopher, Unvrt f 82, Ch, Ch, I, , 4. Sn I rd th ppr t th ACS, I hv xnd ll th 2. Gdn nd , , d., Faraday Rediscovered, vl f th Mechanics Magazine nd d nt fnd th lttr Mlln, ndn, 8, Gldtn ntnd. t hv nfd th zn th . G, Cntr, Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist, nthr jrnl tht I hv nt dvrd. Mlln, ndn, , . S, , hpn, Michael Faraday: His Life and Work, Mlln, Yr, Y, 88, 6. Mrtn, d,, Faraday's Diary (1820-1862),7 l., ll, L, Pearce Williams is John Stambaugh Professor of the ndn, 6. History of Science at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850 . Wll, Michael Faraday, A Biography, Chpn and is author of "Michael Faraday, A Biography" and "The ll, ndn, 6, Origins of Field Theory" He has also edited two volumes of 8. M. rd, Experimental Researches in Electricity, l,, "The Selected Correspondence of Michael Faraday" Qrth, ndn, 88, l , p, . 9. Ibid., l, 2, p. -

SIR EVERARD HOME Address, 1822-25 Reel M604

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT SIR EVERARD HOME Address, 1822-25 Reel M604 Royal College of Surgeons of England 35-43 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3PE National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1951? BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Sir Everard Home (1756-1832), 1st Baronet, was born at Hull, Yorkshire, the son of a former army surgeon. After attending Westminster School, he became a pupil of his brother-in-law, the eminent surgeon John Hunter, at St George’s Hospital, London. He qualified as a surgeon in 1778, was a staff surgeon in the Army for a few years, and then re-joined Hunter as his assistant in teaching, research and clinical practice. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1787. Following Hunter’s death in 1793, Home became surgeon at St George’s Hospital, a position that he held until 1827. In 1799 the Government purchased Hunter’s collection of anatomical and pathological specimens and it was presented to the College of Surgeons. When the Hunterian Museum opened in Lincoln’s Inn Fields 1806, Home was appointed chief curator. He gave the first Hunterian Oration in 1814 and again in 1822. Many of Home’s books and papers, generally published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, were based heavily on Hunter’s unpublished writings. Home was appointed Professor of Anatomy and Surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1814 and he was president of the College in 1821-22. He became surgeon to the Royal Chelsea Hospital in 1821. He was a friend of the Prince Regent, who made him a baronet in 1813.