Creative Nonfiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vocabulary Growth Using Nonfiction Literature and Dialogic Discussions in Preschool Classrooms

Digital Collections @ Dordt Faculty Work Comprehensive List 8-2014 Vocabulary Growth Using Nonfiction Literature and Dialogic Discussions in Preschool Classrooms Gwen R. Marra Dordt College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citation Marra, G. R. (2014). Vocabulary Growth Using Nonfiction Literature and Dialogic Discussions in Preschool Classrooms. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.dordt.edu/faculty_work/69 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Collections @ Dordt. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Work Comprehensive List by an authorized administrator of Digital Collections @ Dordt. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vocabulary Growth Using Nonfiction Literature and Dialogic Discussions in Preschool Classrooms Abstract The preschool years are a crucial time for children to develop vocabulary knowledge. A quality preschool environment promotes large amounts of language usage including picture book read alouds and discussions. There is growing research to support the use of nonfiction literature in preschool classrooms to promote vocabulary growth and knowledge of the world for preschool children. This research study compared vocabulary growth of preschool children using fiction and dialogic discussions ersusv vocabulary growth of preschool children using nonfiction and dialogic discussions following a six week study of autumn and changes that happen during this season to the environment and animals. The quasi- experimental design used the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-4, a curriculum-based measure for receptive vocabulary, and a curriculum-based measure for expressive vocabulary to assess vocabulary growth. -

The Fourth Genre: Creative Nonfiction Joseph Harris Professor of English

The Fourth Genre: Creative Nonfiction Joseph Harris Professor of English Students often read varied and interesting texts in school: stories, poems, plays, speeches, histories, memoirs, accounts of explorations and discoveries, lives of famous people. But what they write tends to be much more limited—usually just paragraphs or brief essays summarizing or analyzing what they’ve read. As a result students often come to see school writing as dull and formulaic, unconnected to what they actually care about. (Or at least this is what many of the freshmen in my college writing classes tell me.) Even those occasional moments when students are asked to compose a story or poem can sometimes seem only to underline the distinction between the fun of creative writing and the routine of most school work. In this seminar we will try to break down the opposition between creative and school writing by looking at what is sometimes called the “fourth genre” of literature. Creative nonfiction is writing about facts—about real people, things, and events. But it is also writing that aims to be as engaging as fiction. The voice of the writer is key. We read a piece of creative nonfiction not only for what it tells us about its subject but also for what we can learn about its author. We’ll approach our study of creative nonfiction in two ways. First, we’ll read and discuss some of the best nonfiction writers at work today—authors like Joyce Carol Oates, Roxanne Gay, Oliver Sacks, Atul Gawande, Ta Nehisi Coates, and Naomi Wolf. -

Genre and Subgenre

Genre and Subgenre Categories of Writing Genre = Category All writing falls into a category or genre. We will use 5 main genres and 15 subgenres. Fiction Drama Nonfiction Folklore Poetry Realistic Comedy Informational Fiction Writing Fairy Tale Tragedy Historical Persuasive Legend Fiction Writing Tall Tale Science Biography Fiction Myth Fantasy Autobiography Fable 5 Main Genres 1. Nonfiction: writing that is true 2. Fiction: imaginative or made up writing 3. Folklore: stories once passed down orally 4. Drama: a play or script 5. Poetry: writing concerned with the beauty of language Nonfiction Subgenres • Persuasive Writing: tries to influence the reader • Informational Writing: explains something • Autobiography: life story written by oneself • Biography: Writing about someone else’s life Latin Roots Auto = Self Bio = Life Graphy = Writing Fiction Subgenres • Historical Fiction: set in the past and based on real people and/or events • Science Fiction: has aliens, robots, futuristic technology and/or space ships • Realistic Fiction: has no elements of fantasy; could be true but isn’t • Fantasy: has monsters, magic, or characters with superpowers Folklore Subgenres Folklore/Folktales usually has an “unknown” author or will be “retold” or “adapted” by the author. • Fable: short story with personified animals and a moral Personified: given the traits of people Moral: lesson or message of a fable • Myth: has gods/goddesses and usually accounts for the creation of something Folklore Subgenres (continued) Tall Tale • Set in the Wild West, the American frontier • Main characters skills/size/strength is greatly exaggerated • Exaggeration is humorous Legend • Based on a real person or place • Facts are stretched beyond nonfiction • Exaggerated in a serious way Folklore Subgenres (continued) Fairytale: has magic and/or talking animals. -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

Science Fiction

Science Fiction The Lives of Tao by Wesley Chu When out-of-shape IT technician Roen Tan woke up and started hearing voices in his head, he naturally assumed he was losing it. He wasn’t. He now has a passenger in his brain – an ancient alien life-form called Tao, whose race crash-landed on Earth before the first fish crawled out of the oceans. Now split into two opposing factions – the peace-loving, but under-represented Prophus, and the savage, powerful Genjix – the aliens have been in a state of civil war for centuries. Both sides are searching for a way off-planet, and the Genjix will sacrifice the entire human race, if that’s what it takes. Meanwhile, Roen is having to train to be the ultimate secret agent. Like that’s going to end up well… 2014 YALSA Alex Award winner The Testing (The Testing Trilogy Series #1) by Joelle Charbonneau It’s graduation day for sixteen-year-old Malencia Vale, and the entire Five Lakes Colony (the former Great Lakes) is celebrating. All Cia can think about—hope for— is whether she’ll be chosen for The Testing, a United Commonwealth program that selects the best and brightest new graduates to become possible leaders of the slowly revitalizing post-war civiliZation. When Cia is chosen, her father finally tells her about his own nightmarish half-memories of The Testing. Armed with his dire warnings (”Cia, trust no one”), she bravely heads off to Tosu City, far away from friends and family, perhaps forever. Danger, romance—and sheer terror—await. -

Foundations of ELA Honors 9

PLANNED COURSE OF STUDY Course Title Foundations of High School English Language Arts - Honors Grade Level Ninth Grade Credits 2 Content Area / English Language Arts Dept. Length of Course One Year Author(s) Course Description: Foundations of ELA 9 Honors is designed to take students on a reflective and evaluative exploration of both classic and contemporary texts. Students will have the opportunity to explore the texts independently, as well as in cooperative groups, while demonstrating initiative and comprehension through manipulation of the text. Through the study of core texts—Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Homer’s The Odyssey, Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese, and William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet-- students will delve into the structure of language with a focus on specific themes, such as the journey as a metaphor, fate vs. free will, trust, coping with change, the struggles of overcoming obstacles, and perseverance in the face of adversity and stereotypes. While actively seeking and recognizing thematic strands within the texts, students will be encouraged to form personal and creative connections to their lives and to the world around them. Students will also engage in a study of selected poems and short works to closely analyze literary devices in connection to the author’s purpose. In addition, Foundations of ELA 9 Honors requires students to analyze literature and rhetoric with intellectual curiosity, persistence, and a readiness to engage in independent risk- taking. ELA 9 Honors students will be expected to process course material with an increased pace and demonstrate critical thinking skills with limited guidance. Course Rationale: Many of the works read in our ninth-grade curriculum are the most celebrated canonical pieces of their time. -

An Analysis of Narrative and Voice in Creative Nonfiction

An Analysis of Narrative and Voice in Creative Nonfiction Michael Pickett1 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Available Online August 2013 This manuscript surveys and analyzes the relationships between 25 Key words: published essays identified in the book In Fact: The Best of Creative Narratological Framework; Nonfiction using Jahn’s (2003) narratological framework in an attempt Narratological Relationships; to identify the narratological relationships between fiction and creative Creative Nonfiction. nonfiction and to analyze creative nonfiction through a narratological framework created for fiction. All of the surveyed stories contained many indicators that contribute to a deepened engagement for the readers, however at the individual writer level; the lowest common denominator is each writer’s ability to forge ahead and continue to create a narrative that develops meaning for the readers beyond the mere reporting of events. Areas identified for further research includes experimental research in the areas of cross-cultural cognitive models that could provide insights concerning the existence of an unreliable narrator within narrative discourse. In addition research could be pursued in the areas of structural discourse of the narrative, much like Jahn’s model, yet somewhat more cognitive juxtaposing the more psychological aspects of narrative discourse to the structural components. 1.0 INTRODUCTION The beginning is the most important part of the work. Plato As with any major undertaking whether it is an anthology, essay, or research project, the beginning is the most difficult part. Therefore, after many hours of research and reading, I had always wondered, what makes creative nonfiction successful? Could it be the story itself, regardless of who the author was? No, that really cannot be the answer because there are many good writers who are not as well recognized as they might have been, even with famous or infamous stories. -

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name: ENGL049 - Accelerated Reading and RDNG 116 - College Reading and Study Skills Student may need to Writing Skills for ENGL100 OR take the following ENGL098 - Accelerated Writing Skills for MATH 090 - Pre-Algebra courses: ENGL100 MATH 095 - Beginning Algebra Grade Earned Semester Course Requirement Course Title Credits Min. Grade T - Transfer Completed FIRST YEAR FALL ENGL 100 Academic Writing I 1 3 C ENGL 135 OR Short Narrative Film Writing OR ENGL 261 Visiting Writer Series 1 Liberal Arts Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Mathematics Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Social Sciences Elective 3 Unrestricted Elective 2 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 101 Academic Writing II 3 3 ENGL 102 Approaches to Literature 3 3 ENGL 200 Screenwriting 3 ENGL 233 Film Analysis 3 SUNY GEN ED Science Elective 4 3 Total Credits 15 SECOND YEAR FALL ENGL 201 OR Public Speaking OR 3 ENGL 204 Interpersonal Communication ENGL 216 Advanced Screenwriting 3 ENGL 256 Playwriting or ENGL Elective 3 ENGL 274 Marketing the Screenplay 1 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 5 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 237 OR Journalism OR ENGL 258 Creative Nonfiction 3 ENGL 255 Writing Television Drama & Comedy 3 5 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Restricted Elective 7 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 15 Minimum Credits Required for Graduation: 62 1 A C or better grade is required in ENGL 100. A student exempted from ENGL 100 must substitute a three credit liberal arts elective. -

Sweet Is Crème Brûlée

4.3 Letter from the Editor As I write this, we're still in April—National Poetry Month. In the Tampa area, there will have been at least 17 readings this month, including a number sponsored by community groups and held at local coffee shops and bars—a surfeit of poetry. Social media is exploding with links to great poems. A friend hosted a party for which we were encouraged to show up in pajamas and read a favorite poem or two. (For the record, my sleepwear was an old t-shirt of Ira's and a pair of comfy shorts, but the apartment was so deeply air-conditioned that I envied those who had worn their fuzzy slippers.) What a time to be a poet, or a reader of poetry! And yet...there are moments when even I am a little overloaded with poetry. When it comes to feel like an obligation. It's mid-month, and I've only made it to three poetry events so far. Yes, sometimes during the events I'm doing my own necessary work. But sometimes I'm watching Dr. Who on Netflix and eating Cadbury chocolate eggs, letting my brain flatten out like the surface of a swimming pool when everybody's finally gotten out and grabbed their towels. I'm distressed by my own behavior. After all, I belong to the church of poetry. Poetry is the closest I get to religion. It's what connects me to the mystery, to people, to the world. I'm finally coming to understand it, though. -

The Effectiveness of Fiction Versus Nonfiction in Teaching Reading to Esl Students

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 The effectiveness of fiction ersusv nonfiction in teaching reading to ESL students Becky Kay Appley Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Appley, Becky Kay, "The effectiveness of fiction versus nonfiction in teaching eadingr to ESL students" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3754. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5639 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Becky Kay Appley for the Master of Arts in English: TESOL presented July 11, 1988. Title: The Effectiveness of Fiction Versus NonFiction in Teaching Reading to ESL Students. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Marjorie Terdal, Chairman Shelley .H Charles LeGuin ~ In recent years with the growing emphasis upon communi- cative activities in the classroom, controversy has risen as to which type of reading material is best for teaching reading in the ESL cla3sroom, fiction or nonfiction. 2 A study was conducted with 31 students of which 15 were taught with non-fiction and 16 were taught with fiction. Both groups were taught the same reading skills. Each group was given three pre-tests and three post-tests in which improvement in overall language proficiency and reading comprehension in the areas of main idea, direct statements and inferences was measured. -

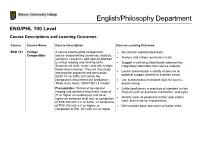

ENG/PHL 100 Level Course Descriptions & Learning Outcomes

English/Philosophy Department ENG/PHL 100 Level Course Descriptions and Learning Outcomes Course Course Name Course Description Course Learning Outcome ENG 101 College A course emphasizing college-level, • Summarize sophisticated texts. Composition source- based writing (summary, analysis, • Analyze and critique persuasive texts. synthesis, research), with special attention to critical reading and thinking skills. • Support a well-articulated thesis statement by Students will draft, revise, and edit multiple integrating information from source material. thesis-driven essays. They will also study • Locate and evaluate a variety of sources as and practice argument and persuasion. potential support material in a written essay. (ENG 101 or ENG 200 satisfy the composition requirement for graduation.) • Use standard documentation style for source- Three class hours. (SUNY-BC) 3 Credits. based writing. Prerequisites: Waiver of Accuplacer • Exhibit proficiency in practices of standard written reading and sentence level tests; score of English (such as grammar, mechanics, and style). 71 or higher on reading test and 82 or • higher on sentence level test; or completion Identify areas of weakness in their own written of TRS 200 with a C or better; or completion work, and revise for improvement. of TRS 105 with a C or higher; or • Demonstrate basic oral communication skills completion of ESL 201 with a C or higher. Course Course Name Course Description Course Learning Outcome ENG Introduction to An introduction to reading and analyzing • Write thesis-driven, evidence-based literary 105 Literature these primary genres of literature: fiction, arguments, using literature as a primary source poetry, and drama. The course may also and relying on textual support. -

Writer's Workshop: Creative Writing 1

Writer's Workshop: Creative Writing 1 WRWS 1500 INTRODUCTION TO CREATIVE WRITING (3 credits) WRITER'S WORKSHOP: An introduction for non-majors in creative writing to the art and craft of writing fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Follows a workshop format based on individual and group critique of students' writing, discussion CREATIVE WRITING of principles and techniques of the craft, and reading and analysis of instructive literary examples. The Writer’s Workshop mission is to offer creative writing students an Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): ENGL1160 apprenticeship with professional writers. We prepare students to read Distribution: Humanities and Fine Arts General Education course closely, think critically, write professionally and find their voices in poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and screenwriting. Students will also sharpen WRWS 2000 SPECIAL STUDIES IN WRITING (3 credits) their capacity for empathy, opening themselves to diverse cultural points of Offers varying subjects in writing and reading for the basic study of special view. forms, structures and techniques of imaginative literature. Consult the current class schedule for the semester's subject. May be repeated for credit Other Information with change of subject. Thesis Option Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): ENGL 1160. Not open to non-degree graduate students. Students whose work is above average and who are considering doing graduate work in creative writing may apply after one Advanced Studio to WRWS 2050 FUNDAMENTALS OF FICTION WRITING (3 credits) pursue the BFA with Senior Thesis. The result is a book-length manuscript A study of the ways in which writers confront the technical choices of their of original work in the student’s area of concentration (e.g.