Sweet Is Crème Brûlée

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fourth Genre: Creative Nonfiction Joseph Harris Professor of English

The Fourth Genre: Creative Nonfiction Joseph Harris Professor of English Students often read varied and interesting texts in school: stories, poems, plays, speeches, histories, memoirs, accounts of explorations and discoveries, lives of famous people. But what they write tends to be much more limited—usually just paragraphs or brief essays summarizing or analyzing what they’ve read. As a result students often come to see school writing as dull and formulaic, unconnected to what they actually care about. (Or at least this is what many of the freshmen in my college writing classes tell me.) Even those occasional moments when students are asked to compose a story or poem can sometimes seem only to underline the distinction between the fun of creative writing and the routine of most school work. In this seminar we will try to break down the opposition between creative and school writing by looking at what is sometimes called the “fourth genre” of literature. Creative nonfiction is writing about facts—about real people, things, and events. But it is also writing that aims to be as engaging as fiction. The voice of the writer is key. We read a piece of creative nonfiction not only for what it tells us about its subject but also for what we can learn about its author. We’ll approach our study of creative nonfiction in two ways. First, we’ll read and discuss some of the best nonfiction writers at work today—authors like Joyce Carol Oates, Roxanne Gay, Oliver Sacks, Atul Gawande, Ta Nehisi Coates, and Naomi Wolf. -

Creative Nonfiction

WRITING CREATIVE NON-FICTION THEODORE A. REES CHENEY CREATIVE NONFICTION Creative nonfiction tells a story using facts, but uses many of the techniques of fiction for its compelling qualities and emotional vibrancy. Creative nonfiction doesn’t just report facts, it delivers facts in ways that move the reader toward a deeper understanding of a topic. Creative nonfiction requires the skills of the storyteller and the research ability of the conscientious reporter. Writers of creative nonfiction must become instant authorities on the subject of their articles or books. They must not only understand the facts and report them using quotes by authorities, they must also see beyond them to discover their underlying meaning, and they must dramatize that meaning in an interesting, evocative, informative way—just as a good teacher does. When you write nonfiction, you are, in effect, teaching the reader. Research into how we learn shows that we learn best when we are simultaneously entertained—when there is pleasure in the learning. Other research shows that our most lasting memories are those wrapped in emotional overtones. Creative nonfiction writers inform their readers by making the reading experience vivid, emotionally compelling, and enjoyable while sticking to the facts. TELLING THE “WHOLE TRUTH” Emotions inform our understanding all the time. So, to tell the whole truth about most situations that involve people (and most situations do), in the words of Tom Wolfe, we need to “excite the reader both intellectually and emotionally.” The best nonfiction writers do not tell us how we should think about something, how we should feel about it, nor what emotions should be aroused. -

Foundations of ELA Honors 9

PLANNED COURSE OF STUDY Course Title Foundations of High School English Language Arts - Honors Grade Level Ninth Grade Credits 2 Content Area / English Language Arts Dept. Length of Course One Year Author(s) Course Description: Foundations of ELA 9 Honors is designed to take students on a reflective and evaluative exploration of both classic and contemporary texts. Students will have the opportunity to explore the texts independently, as well as in cooperative groups, while demonstrating initiative and comprehension through manipulation of the text. Through the study of core texts—Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, Homer’s The Odyssey, Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese, and William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet-- students will delve into the structure of language with a focus on specific themes, such as the journey as a metaphor, fate vs. free will, trust, coping with change, the struggles of overcoming obstacles, and perseverance in the face of adversity and stereotypes. While actively seeking and recognizing thematic strands within the texts, students will be encouraged to form personal and creative connections to their lives and to the world around them. Students will also engage in a study of selected poems and short works to closely analyze literary devices in connection to the author’s purpose. In addition, Foundations of ELA 9 Honors requires students to analyze literature and rhetoric with intellectual curiosity, persistence, and a readiness to engage in independent risk- taking. ELA 9 Honors students will be expected to process course material with an increased pace and demonstrate critical thinking skills with limited guidance. Course Rationale: Many of the works read in our ninth-grade curriculum are the most celebrated canonical pieces of their time. -

An Analysis of Narrative and Voice in Creative Nonfiction

An Analysis of Narrative and Voice in Creative Nonfiction Michael Pickett1 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Available Online August 2013 This manuscript surveys and analyzes the relationships between 25 Key words: published essays identified in the book In Fact: The Best of Creative Narratological Framework; Nonfiction using Jahn’s (2003) narratological framework in an attempt Narratological Relationships; to identify the narratological relationships between fiction and creative Creative Nonfiction. nonfiction and to analyze creative nonfiction through a narratological framework created for fiction. All of the surveyed stories contained many indicators that contribute to a deepened engagement for the readers, however at the individual writer level; the lowest common denominator is each writer’s ability to forge ahead and continue to create a narrative that develops meaning for the readers beyond the mere reporting of events. Areas identified for further research includes experimental research in the areas of cross-cultural cognitive models that could provide insights concerning the existence of an unreliable narrator within narrative discourse. In addition research could be pursued in the areas of structural discourse of the narrative, much like Jahn’s model, yet somewhat more cognitive juxtaposing the more psychological aspects of narrative discourse to the structural components. 1.0 INTRODUCTION The beginning is the most important part of the work. Plato As with any major undertaking whether it is an anthology, essay, or research project, the beginning is the most difficult part. Therefore, after many hours of research and reading, I had always wondered, what makes creative nonfiction successful? Could it be the story itself, regardless of who the author was? No, that really cannot be the answer because there are many good writers who are not as well recognized as they might have been, even with famous or infamous stories. -

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name

Creative Writing, A.A. - Screenwriting Concentration Fall 2020 Student's Name: Advisor's Name: ENGL049 - Accelerated Reading and RDNG 116 - College Reading and Study Skills Student may need to Writing Skills for ENGL100 OR take the following ENGL098 - Accelerated Writing Skills for MATH 090 - Pre-Algebra courses: ENGL100 MATH 095 - Beginning Algebra Grade Earned Semester Course Requirement Course Title Credits Min. Grade T - Transfer Completed FIRST YEAR FALL ENGL 100 Academic Writing I 1 3 C ENGL 135 OR Short Narrative Film Writing OR ENGL 261 Visiting Writer Series 1 Liberal Arts Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Mathematics Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Social Sciences Elective 3 Unrestricted Elective 2 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 101 Academic Writing II 3 3 ENGL 102 Approaches to Literature 3 3 ENGL 200 Screenwriting 3 ENGL 233 Film Analysis 3 SUNY GEN ED Science Elective 4 3 Total Credits 15 SECOND YEAR FALL ENGL 201 OR Public Speaking OR 3 ENGL 204 Interpersonal Communication ENGL 216 Advanced Screenwriting 3 ENGL 256 Playwriting or ENGL Elective 3 ENGL 274 Marketing the Screenplay 1 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 5 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 16 SPRING ENGL 237 OR Journalism OR ENGL 258 Creative Nonfiction 3 ENGL 255 Writing Television Drama & Comedy 3 5 SUNY GEN ED Foreign Language Sequence Elective 3 SUNY GEN ED Restricted Elective 7 3 Unrestricted Elective 6 3 Total Credits 15 Minimum Credits Required for Graduation: 62 1 A C or better grade is required in ENGL 100. A student exempted from ENGL 100 must substitute a three credit liberal arts elective. -

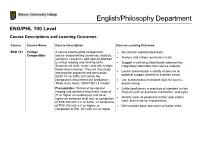

ENG/PHL 100 Level Course Descriptions & Learning Outcomes

English/Philosophy Department ENG/PHL 100 Level Course Descriptions and Learning Outcomes Course Course Name Course Description Course Learning Outcome ENG 101 College A course emphasizing college-level, • Summarize sophisticated texts. Composition source- based writing (summary, analysis, • Analyze and critique persuasive texts. synthesis, research), with special attention to critical reading and thinking skills. • Support a well-articulated thesis statement by Students will draft, revise, and edit multiple integrating information from source material. thesis-driven essays. They will also study • Locate and evaluate a variety of sources as and practice argument and persuasion. potential support material in a written essay. (ENG 101 or ENG 200 satisfy the composition requirement for graduation.) • Use standard documentation style for source- Three class hours. (SUNY-BC) 3 Credits. based writing. Prerequisites: Waiver of Accuplacer • Exhibit proficiency in practices of standard written reading and sentence level tests; score of English (such as grammar, mechanics, and style). 71 or higher on reading test and 82 or • higher on sentence level test; or completion Identify areas of weakness in their own written of TRS 200 with a C or better; or completion work, and revise for improvement. of TRS 105 with a C or higher; or • Demonstrate basic oral communication skills completion of ESL 201 with a C or higher. Course Course Name Course Description Course Learning Outcome ENG Introduction to An introduction to reading and analyzing • Write thesis-driven, evidence-based literary 105 Literature these primary genres of literature: fiction, arguments, using literature as a primary source poetry, and drama. The course may also and relying on textual support. -

Writer's Workshop: Creative Writing 1

Writer's Workshop: Creative Writing 1 WRWS 1500 INTRODUCTION TO CREATIVE WRITING (3 credits) WRITER'S WORKSHOP: An introduction for non-majors in creative writing to the art and craft of writing fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. Follows a workshop format based on individual and group critique of students' writing, discussion CREATIVE WRITING of principles and techniques of the craft, and reading and analysis of instructive literary examples. The Writer’s Workshop mission is to offer creative writing students an Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): ENGL1160 apprenticeship with professional writers. We prepare students to read Distribution: Humanities and Fine Arts General Education course closely, think critically, write professionally and find their voices in poetry, fiction, creative nonfiction, and screenwriting. Students will also sharpen WRWS 2000 SPECIAL STUDIES IN WRITING (3 credits) their capacity for empathy, opening themselves to diverse cultural points of Offers varying subjects in writing and reading for the basic study of special view. forms, structures and techniques of imaginative literature. Consult the current class schedule for the semester's subject. May be repeated for credit Other Information with change of subject. Thesis Option Prerequisite(s)/Corequisite(s): ENGL 1160. Not open to non-degree graduate students. Students whose work is above average and who are considering doing graduate work in creative writing may apply after one Advanced Studio to WRWS 2050 FUNDAMENTALS OF FICTION WRITING (3 credits) pursue the BFA with Senior Thesis. The result is a book-length manuscript A study of the ways in which writers confront the technical choices of their of original work in the student’s area of concentration (e.g. -

Collected Essays a Dissertation Presented

Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight: Collected Essays A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Wesley D. Roj August 2016 © 2016 Wesley D. Roj. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight: Collected Essays by WESLEY D. ROJ has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Eric LeMay Associate Professor of English Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT ROJ, WESLEY., Ph.D., December 2016, English Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight: Collected Essays Director of Dissertation: Eric LeMay Ten Impossible Things Before Daylight is a collection of essays which turn on experiences with the uncanny, including premonitions, visitations, bizarre coincidences, impactful dreams, and lucky charms. My essays seek to explore a side of the uncanny that is not horrific but instead, eerily invigorating. The lead-off essay “Goodnight Noises” is an uncanny elegy for friend that I knew since childhood who tragically developed severe schizophrenia. My essay is about making sense of his somewhat mysterious disappearance and death. “Far and Wee” is the story of the unplanned rescue of a baby goat that my wife and I found in an ocean while on vacation. Our rescue of the goat led us to many moments of prescience regarding the birth of our firstborn son. The collection is a varied and confessional portrait of my evolving sense of the uncanny and its influence over the red letter days of my life. -

Writing Creative Nonfiction Essays Alexis Karsjens Supervisor: Dr

“Coming Home”: Writing Creative Nonfiction Essays Alexis Karsjens Supervisor: Dr. Samuel Martin Department of English The Craft of Nonfiction Abstract LEARNING FROM the Essayists “Coming Home” is a collection of creative nonfiction essays that explore what home can represent. The essays Phillip Lopate’s To Show and To Tell: The Craft of explore the importance of family and finding belonging in the midst of an ever-changing environment. The idea “Travels with Charley: In Search of Literary Nonfiction categorizes the creative and reality of place is at the heart of the collection, in which I reflect on my personal experiences of growing up America” by John Steinbeck nonfiction essay as “tracking the consciousness of on a farm in Northeast Iowa. The essay “Emerald Green Beans” is a reflection on a visit to my grandmother’s the author” (6). home after receiving a suicidal phone call from her, and further exploring her memories of her now-vanished Steinbeck offers what seems to be a series of essays hometown of Eleanor, Iowa. In “When the Grass Speaks,” I weave natural science and my passion for my that are quite simple in style yet poignant. Much of Important aspects of the genre: farm’s yard into an extended metaphor for the ongoing destruction of agricultural lands in the Midwest due to his prose starts with a “Truth” followed by an harmful farming practices. And my essay “Going Home” is an abstract reflection on the COVID-19 pandemic example of that truth on the journey. The overarching • Curiosity and the seasonal change of a small field buffer near my family’s farm. -

TELLING the TRUTH: CREATIVE NONFICTION in CAPOTE's in COLD BLOOD & MAILER's the EXECUTIONER's SONG by James R. Capp A

TELLING THE TRUTH: CREATIVE NONFICTION IN CAPOTE’S IN COLD BLOOD & MAILER’S THE EXECUTIONER’S SONG by James R. Capp A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Wilkes Honors College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences with a Concentration in English Literature Wilkes Honors College of Florida Atlantic University Jupiter, Florida May 2008 TELLING THE TRUTH: CREATIVE NONFICTION IN CAPOTE’S IN COLD BLOOD & MAILER’S THE EXECUTIONER’S SONG by James R. Capp This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor, Dr. Laura Barrett, and has been approved by the members of her/his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Honors College and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Liberal Arts and Sciences. SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ____________________________ Dr. Laura Barrett ____________________________ Prof. James McGarrah ______________________________ Dean, Wilkes Honors College ____________ Date ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Obviously, I need to express my gratitude to Dr. Laura Barrett for her tremendous display of advising skills and for her infinite patience. Additionally, I wish to thank certain persons whose contributions to my work were of great importance: Professor Jim McGarrah, who jumped into this project with great enthusiasm; Mr. Peter Salomone, whose encouraging words and constructive criticism were essential to the completion of this thesis; the lovely Ms. Cara Piccirillo, who stood by me through it all; and finally, all of my professors, friends and family. You were all wonderful for supporting me throughout the years, and you were all especially kind during the home stretch of this project when I broke my right hand. -

Creative Writing Courses

San Diego City College English Department Creative Writing Courses Contacts Chris Baron [email protected] Twitter: @baronchrisbaron Instagram: christhebearbaron Website: Chris-baron.com Patricia McGhee [email protected] Description Are you interested in writing poetry, short stories, or personal narratives? The Creative Writing program at City College offers exciting classes to explore your voice as a writer. City College offers a 15-unit Certificate of Performance in Creative Writing. Our dynamic faculty are poets, fiction writers and essayists who create courses designed to help you to explore different genres of writing. Which courses can I take? (Please note that you do not need to take these courses in sequential order) • English 36 Basic Creative Writing Workshop If you have not taken English 101 yet, you can still take English 36. This class may run concurrently with one of the below sections and is not a transfer level English class. • English 245 A/B Creative Nonfiction This course explores personal essay writing. • English 247 A/B Poetry In this class you will write different Kinds of poems which may include free verse, spoKen word, and formal verse. Rev. April 2021 San Diego City College English Department • English 249 Introduction to Creative Writing This introductory class explores the writing of poetry, fiction and creative non-fiction. You can take this class twice as 249 A and 249 B. You do not need to take this class before taking 245, 252, or 247. In spring semesters, this course edits and produces City WorKs literary journal. • English 252 A/B Fiction In this class you will deepen your exploration of writing fiction, including flash fiction, micro fiction, short stories, and novels. -

Literature 1

Literature 1 Literature LIT 1510. Independent Study. 1-5 Unit. LIT 2510. Independent Study. 1-5 Unit. LIT 3040. Transforming Literature Into Film: Women Novelists and the Male Cinematic Gaze. 3-4 Unit. This course offers an exploration of novels written by women and investigates how they translate into films directed by men. Viewing the films and reading the novels on which they are based, students examine the content, ideas, and meaning of each work of literature and how the film version embellishes or diminishes this meaning. LIT 3100. Modern European Fiction. 3-4 Unit. The early twentieth century marks a time of crisis in Western culture. It was the advent of an era that historian Eric Hobsbawm has labeled the age of extremes. World war laid waste to the empires and social order of the past along with previously unshakeable faith in reason and progress. And it was a time when fixed notions of the self and its place in the world, notions of reality itself, and long-established forms of art collapsed in a radical break with tradition that gave way to an utterly new form language in all of the arts. This course focuses on modernist innovations in the art of fiction by examining four pioneering texts - all of which can be read and reread without exhausting their depths - as seen in this rich and tumultuous historical context: Death in Venice (1911) by Thomas Mann, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1914) by James Joyce, Swann's Way (1913) by Marcel Proust, and To the Lighthouse (1927) by Virginia Woolf.