Of Vice and Men: an Ethnographic Content Analysis of the Manosphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: to Stop the Defamation of the Jewish People and to Secure Justice and Fair Treatment for All

A report from the Center on Extremism 09 18 New Hate and Old: The Changing Face of American White Supremacy Our Mission: To stop the defamation of the Jewish people and to secure justice and fair treatment for all. ABOUT T H E CENTER ON EXTREMISM The ADL Center on Extremism (COE) is one of the world’s foremost authorities ADL (Anti-Defamation on extremism, terrorism, anti-Semitism and all forms of hate. For decades, League) fights anti-Semitism COE’s staff of seasoned investigators, analysts and researchers have tracked and promotes justice for all. extremist activity and hate in the U.S. and abroad – online and on the ground. The staff, which represent a combined total of substantially more than 100 Join ADL to give a voice to years of experience in this arena, routinely assist law enforcement with those without one and to extremist-related investigations, provide tech companies with critical data protect our civil rights. and expertise, and respond to wide-ranging media requests. Learn more: adl.org As ADL’s research and investigative arm, COE is a clearinghouse of real-time information about extremism and hate of all types. COE staff regularly serve as expert witnesses, provide congressional testimony and speak to national and international conference audiences about the threats posed by extremism and anti-Semitism. You can find the full complement of COE’s research and publications at ADL.org. Cover: White supremacists exchange insults with counter-protesters as they attempt to guard the entrance to Emancipation Park during the ‘Unite the Right’ rally August 12, 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. -

Gynocentrism As a Narcissistic Pathology

24 GYNOCENTRISM AS A NARCISSISTIC PATHOLOGY Peter Wright ABSTRACT Gynocentrism is defined as the practice of prioritizing the needs, wants and desires of women. Examples of gynocentrism are found in the culture of social institutions, and within heterosexual relationships where men are invited to show deference to the needs, wants and desires of women, a practice otherwise referred to as chivalry or benevolent sexism. This study compares gynocentric behaviors with clinical descriptions of narcissism to discover how closely, and in what ways, the two concepts align. The investigation concludes that narcissistic behavior is significantly correlated with behaviors of gynocentrically oriented women, and that gynocentrism is a gendered expression of narcissism operating within the limiting context of heterosexual relationships and exchanges. Keywords: Gynocentrism, chivalry, benevolent sexism, narcissism, narcissistic personality inventory, gender NEW MALE STUDIES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ~ ISSN 1839-7816 ~ Vol 9, Issue 1, 2020, Pp. 24–49 © 2020 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF MALE HEALTH AND STUDIES 25 INTRODUCTION Gynocentrism has been described as a practice of prioritizing the needs, wants and desires of women over those of men. It operates within a moral hierarchy that emphasizes the innate virtues and vulnerabilities of women and the innate vices of men, thus providing a rationale for placing women’s concerns and perspectives ‘on top’, and men’s at the bottom (Nathanson & Young, 2006; 2010). The same moral hierarchy has been institutionalized in social conventions, laws and interpretations of them, in constitutional amendments and their interpretive guidelines, and bureaucracies at every level of government, making gynocentrism de rigueur behind the scenes in law courts and government bureaucracies that result in systemic discrimination against men (Nathanson & Young, 2006; Wright, 2018a; Wallace et al., 2019; Naurin, 2019). -

![Arxiv:2001.07600V5 [Cs.CY] 8 Apr 2021 Leged Crisis (Lilly 2016)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6394/arxiv-2001-07600v5-cs-cy-8-apr-2021-leged-crisis-lilly-2016-86394.webp)

Arxiv:2001.07600V5 [Cs.CY] 8 Apr 2021 Leged Crisis (Lilly 2016)

The Evolution of the Manosphere Across the Web* Manoel Horta Ribeiro,♠;∗ Jeremy Blackburn,4 Barry Bradlyn,} Emiliano De Cristofaro,r Gianluca Stringhini,| Summer Long,} Stephanie Greenberg,} Savvas Zannettou~;∗ EPFL, Binghamton University, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign University♠ College4 London, Boston} University, Max Planck Institute for Informatics r Corresponding authors: manoel.hortaribeiro@epfl.ch,| ~ [email protected] ∗ Abstract However, Manosphere communities are scattered through the Web in a loosely connected network of subreddits, blogs, We present a large-scale characterization of the Manosphere, YouTube channels, and forums (Lewis 2019). Consequently, a conglomerate of Web-based misogynist movements focused we still lack a comprehensive understanding of the underly- on “men’s issues,” which has prospered online. Analyzing 28.8M posts from 6 forums and 51 subreddits, we paint a ing digital ecosystem, of the evolution of the different com- comprehensive picture of its evolution across the Web, show- munities, and of the interactions among them. ing the links between its different communities over the years. Present Work. In this paper, we present a multi-platform We find that milder and older communities, such as Pick longitudinal study of the Manosphere on the Web, aiming to Up Artists and Men’s Rights Activists, are giving way to address three main research questions: more extreme ones like Incels and Men Going Their Own Way, with a substantial migration of active users. Moreover, RQ1: How has the popularity/levels of activity of the dif- our analysis suggests that these newer communities are more ferent Manosphere communities evolved over time? toxic and misogynistic than the older ones. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

What Is Gab? a Bastion of Free Speech Or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?

What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber? Savvas Zannettou Barry Bradlyn Emiliano De Cristofaro Cyprus University of Technology Princeton Center for Theoretical Science University College London [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Haewoon Kwak Michael Sirivianos Gianluca Stringhini Qatar Computing Research Institute Cyprus University of Technology University College London & Hamad Bin Khalifa University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn University of Alabama at Birmingham [email protected] ABSTRACT ACM Reference Format: Over the past few years, a number of new “fringe” communities, Savvas Zannettou, Barry Bradlyn, Emiliano De Cristofaro, Haewoon Kwak, like 4chan or certain subreddits, have gained traction on the Web Michael Sirivianos, Gianluca Stringhini, and Jeremy Blackburn. 2018. What is Gab? A Bastion of Free Speech or an Alt-Right Echo Chamber?. In WWW at a rapid pace. However, more often than not, little is known about ’18 Companion: The 2018 Web Conference Companion, April 23–27, 2018, Lyon, how they evolve or what kind of activities they attract, despite France. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3184558. recent research has shown that they influence how false informa- 3191531 tion reaches mainstream communities. This motivates the need to monitor these communities and analyze their impact on the Web’s information ecosystem. 1 INTRODUCTION In August 2016, a new social network called Gab was created The Web’s information ecosystem is composed of multiple com- as an alternative to Twitter. -

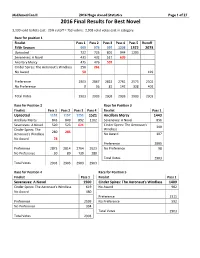

2016 Statistics Document

MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novel 3,130 valid ballots cast. 25% cutoff = 753 voters. 2,903 valid votes cast in category. Race for position 1 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Pass 5 Runoff Fifth Season 969 973 997 1208 1372 2073 Uprooted 722 725 801 944 1203 Seveneves: A Novel 431 432 517 609 Ancillary Mercy 475 476 507 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 256 261 No Award 50 429 Preference 2903 2867 2822 2761 2575 2502 No Preference 0 36 81 142 328 401 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 2 Race for Position 3 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Finalist Pass 1 Uprooted 1152 1157 1251 1521 Ancillary Mercy 1443 Ancillary Mercy 843 849 892 1102 Seveneves: A Novel 856 Seveneves: A Novel 520 523 621 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's 399 Cinder Spires: The Windlass 280 285 Aeronaut's Windlass No Award 107 No Award 78 Preference 2805 Preference 2873 2814 2764 2623 No Preference 98 No Preference 30 89 139 280 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 4 Race for Position 5 Finalist Pass 1 Finalist Pass 1 Seveneves: A Novel 1500 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 1409 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 619 No Award 902 No Award 480 Preference 2311 Preference 2599 No Preference 592 No Preference 304 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novella 3,130 valid ballots cast. -

7. Not So Romantic for Men

DENNIS S. GOUWS 7. NOT SO ROMANTIC FOR MEN Using Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe to Explore Evolving Notions of Chivalry and Their Impact on Twenty-First-Century Manhood THE NEED FOR A NEW MALE STUDIES The New Male Studies offer an alternative to conventional gender-based scholarship on boys and men.1 Unlike Men’s-Studies research, which is fundamentally informed by gender feminism, New-Male-Studies research focusses on boys’ and men’s lived experiences and shares its concern about gender discrimination against all people with equity feminism.2 The New Male Studies are embodied and male positive (male affirming): their approach to manhood, which results when one “configure[s] biological masculinity to meet the particular demands of a specific culture and environmental setting,” not only celebrates males’ experience of different manhood cultures and subcultures, but also critiques—and suggests strategies for overcoming—systemic inhibitors of masculine affirmation (Ashfield, 2011, p. 28; Gilmore, 1990). An acute attentiveness to how manhood is inscribed in texts, textual criticism, and pedagogy is central to their methodology. In much of Western culture and literature, gynocentric (women-centered) and misandric (male-hating) value judgments have adversely influenced boys’ and men’s lives. For example, pervasive stereotypes of manhood that rely on gynocentric and misandric assumptions about males infer that it is acceptable to regard them as little more than pleasers, placaters, providers, protectors, and progenitors; such stereotypes assume the male body is primarily an instrument of service rather than the dignified embodiment of a sentient boy or a man (Nathanson & Young, 2001, 2006, 2010). -

"If You're Ugly, the Blackpill Is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board

University of Dayton eCommons Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies Women's and Gender Studies Program 2020 "If You're Ugly, the Blackpill is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board Josh Segalewicz University of Dayton Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/wgs_essay Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons eCommons Citation Segalewicz, Josh, ""If You're Ugly, the Blackpill is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board" (2020). Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies. 20. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/wgs_essay/20 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Women's and Gender Studies Program at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. "If You're Ugly, the Blackpill is Born with You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board by Josh Segalewicz Honorable Mention 2020 Joyce Durham Essay Contest in Women's and Gender Studies "If You're Ugly, The Blackpill is Born With You": Sexual Hierarchies, Identity Construction, and Masculinity on an Incel Forum Board Abstract: The manosphere is one new digital space where antifeminists and men's rights activists interact outside of their traditional social networks. Incels, short for involuntary celibates, exist in this space and have been labeled as extreme misogynists, white supremacists, and domestic terrorists. -

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Bridget Christine Gelms Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Dr. Jason Palmeri, Director ______________________________________ Dr. Tim Lockridge, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Michele Simmons, Reader ______________________________________ Dr. Lisa Weems, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT VOLATILE VISIBILITY: THE EFFECTS OF ONLINE HARASSMENT ON FEMINIST CIRCULATION AND PUBLIC DISCOURSE by Bridget C. Gelms As our digital environments—in their inhabitants, communities, and cultures—have evolved, harassment, unfortunately, has become the status quo on the internet (Duggan, 2014 & 2017; Jane, 2014b). Harassment is an issue that disproportionately affects women, particularly women of color (Citron, 2014; Mantilla, 2015), LGBTQIA+ women (Herring et al., 2002; Warzel, 2016), and women who engage in social justice, civil rights, and feminist discourses (Cole, 2015; Davies, 2015; Jane, 2014a). Whitney Phillips (2015) notes that it’s politically significant to pay attention to issues of online harassment because this kind of invective calls “attention to dominant cultural mores” (p. 7). Keeping our finger on the pulse of such attitudes is imperative to understand who is excluded from digital publics and how these exclusions perpetuate racism and sexism to “preserve the internet as a space free of politics and thus free of challenge to white masculine heterosexual hegemony” (Higgin, 2013, n.p.). While rhetoric and writing as a field has a long history of examining myriad exclusionary practices that occur in public discourses, we still have much work to do in understanding how online harassment, particularly that which is gendered, manifests in digital publics and to what rhetorical effect. -

What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels?

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters Peace Studies 5-15-2019 What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels? Olivia Young Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/peace_studies_student_work Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Social Media Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Young, Olivia, "What Role Has Social Media Played in Violence Perpetrated by Incels?" (2019). Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters. 1. https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/peace_studies_student_work/1 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace Studies at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace Studies Student Papers and Posters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peace Studies Capstone Thesis What role has social media played in violence perpetrated by Incels? Olivia Young May 15, 2019 Young, 1 INTRODUCTION This paper aims to answer the question, what role has social media played in violence perpetrated by Incels? Incels, or involuntary celibates, are members of a misogynistic online subculture that define themselves as unable to find sexual partners. Incels feel hatred for women and sexually active males stemming from their belief that women are required to give sex to them, and that they have been denied this right by women who choose alpha males over them. -

Open Chindhade Final Dissertation

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School Department of German PRESENTING AND COMPARING EARLY MARATHI AND GERMAN WOMEN’S FEMINIST WRITINGS (1866-1933): SOME FINDINGS A Dissertation in German by Tejashri Chindhade © 2010 Tejashri Chindhade Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 The dissertation of Tejashri Chindhade was reviewed and approved* by the following: Daniel Purdy Associate Professor of German Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas.O. Beebee Professor of Comparative Literature and German Reiko Tachibana Associate Professor of Japanese and Comparative Literature Kumkum Chatterjee Associate Professor of South Asia Studies B. Richard Page Associate Professor of German and Linguistics Head of the Department of German *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract In this dissertation I present the feminist writings of four Marathi women writers/ activists Savitribai Phule’s “ Prose and Poetry”, Pandita Ramabai’s” The High Caste Hindu Woman”, Tarabai Shinde’s “Stri Purush Tualna”( A comparison between women and men) and Malatibai Bedekar’s “Kalyanche Nihshwas”( “The Sighs of the buds”) from the colonial period (1887-1933) and compare them with the feminist writings of four German feminists: Adelheid Popp’s “Jugend einer Arbeiterin”(Autobiography of a Working Woman), Louise Otto Peters’s “Das Recht der Frauen auf Erwerb”(The Right of women to earn a living..), Hedwig Dohm’s “Der Frauen Natur und Recht” (“Women’s Nature and Privilege”) and Irmgard Keun’s “Gilgi: Eine Von Uns”(Gilgi:one of us) (1886-1931), respectively. This will be done from the point of view of deconstructing stereotypical representations of Indian women as they appear in westocentric practices. -

The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie

#TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism by Cassie Clark B.A. in English and Theatre, May 2007, St. Olaf College A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts May 17, 2015 Thesis directed by Todd Ramlow Adjunct Professor of Women’s Studies This work is dedicated to my grandfather, who, upon being told that I was planning to attend graduate school, responded, “Good, you should have more education than your father.” ii The author wishes to acknowledge Dr. Todd Ramlow for his expertise, knowledge, and encouragement. She also wishes to acknowledge Dr. Alexander Dent for his invaluable guidance regarding the performance of media and digital technologies. iii Abstract of Thesis #TrendingFeminism: The Impact of Digital Feminist Activism As the use of online platforms such as social networking sites, also known as social media, and blogs grew in popularity, feminists began to embrace digital media as a significant space for activism. Digital feminist activism is a new iteration of feminist activism, offering new tools and tactics for feminists to utilize to spread awareness, disseminate information, and mobilize constituents. In this paper I examine the intent, usefulness, and potential impact of digital feminist activism in the United States by analyzing key examples of social movements conducted via digital media. These analyses not only provide useful examples of a variety of digital feminist efforts, they also highlight strengths and weaknesses in each campaign with the aim of improving the impact of future digital feminist campaigns.