Parliamentary Supremacy Undermined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![261 Advocate (Amdt.) [ 18 NOV. 1980 ] Bill, 1980 262](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8855/261-advocate-amdt-18-nov-1980-bill-1980-262-248855.webp)

261 Advocate (Amdt.) [ 18 NOV. 1980 ] Bill, 1980 262

261 Advocate (Amdt.) [ 18 NOV. 1980 ] Bill, 1980 262 THE ADVOCATE (AMENDMENT) i found to be only in these two cities in India BILL, 1980 occasioned a certain amount of controversy. Parliament finally considered it desirable to do THE MINISTER OF LAW, JUSTICE away with the institution of attorneys so that AND COMPANY AFFAIRS (SHRI SHIV there could be a unified bar and only one class SHANKAR): Mr. Deputy Chairman, Sir, I of legal practitioners, namely, advocates. In move: order to give effect to this object, the Advocates (Amendment) Act, 1976 was "That the Bill further to amend the passed which abolished the class of legal prac- Advocates Act, 1961, as passed by the Lok titioners known as attorneys and the pre- Sabha, be taken into consideration." existing attorneys became advocates. However, for the purpose of determining their Sir, this Bill is a very short one which seniority as advocates, their earlier experience seeks to make two small amendments to the and standing as attorney was not taken into account. This resulted in the anomaly of very Advocates Act, 1961. The other House found many senior attorneys, who had been it to be non-controversial and I hope that the practising as such for several years and were as position would not be different in this House. well qualified becoming junior to those advo- cates who joined the legal profession very The first of these amendments is designed much later and whose standing in the to do away with an anomaly which has come profession was less. The views of the Bar to light recently. -

Scanned by Camscanner Scanned by Camscanner Scanned by Camscanner Page 1

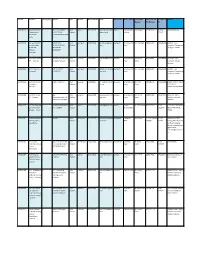

Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Page 1 School-wise pending status of Registration of Class 9th and 11th 2017-18 (upto 10-10-2017) Sl. Dist Sch SchoolName Total09 Entry09 pending_9th Total11 Entry11 1 01 1019 D A V INT COLL DHIMISHRI AGRA 75 74 1 90 82 2 01 1031 ROHTA INT COLL ROHTA AGRA 100 92 8 100 90 3 01 1038 NAV JYOTI GIRLS H S S BALKESHWAR AGRA 50 41 9 0 4 01 1039 ST JOHNS GIRLS INTER COLLEGE 266 244 22 260 239 5 01 1053 HUBLAL INT COLL AGRA 100 21 79 110 86 6 01 1054 KEWALRAM GURMUKHDAS INTER COLLEGE AGRA 200 125 75 200 67 7 01 1057 L B S INT COLL MADHUNAGAR AGRA 71 63 8 48 37 8 01 1064 SHRI RATAN MUNI JAIN INTER COLLEGE AGRA 392 372 20 362 346 9 01 1065 SAKET VIDYAPEETH INTERMEDIATE COLLEGE SAKET COLONY AGRA 150 64 86 200 32 10 01 1068 ST JOHNS INTER COLLEGE HOSPITAL ROAD AGRA 150 129 21 200 160 11 01 1074 SMT V D INT COLL GARHI RAMI AGRA 193 189 4 152 150 12 01 1085 JANTA INT COLL FATEHABAD AGRA 114 108 6 182 161 13 01 1088 JANTA INT COLL MIDHAKUR AGRA 111 110 1 75 45 14 01 1091 M K D INT COLL ARHERA AGRA 98 97 1 106 106 15 01 1092 SRI MOTILAL INT COLL SAIYAN AGRA 165 161 4 210 106 16 01 1095 RASHTRIYA INT COLL BARHAN AGRA 325 318 7 312 310 17 01 1101 ANGLO BENGALI GIRLS INT COLL AGRA 150 89 61 150 82 18 01 1111 ANWARI NELOFER GIRLS I C AGRA 60 55 5 65 40 19 01 1116 SMT SINGARI BAI GIRLS I C BALUGANJ AGRA 70 60 10 100 64 20 01 1120 GOVT GIRLS INT COLL ANWAL KHERA AGRA 112 107 5 95 80 21 01 1121 S B D GIRLS INT COLL FATEHABAD AGRA 105 104 1 47 47 22 01 1122 SHRI RAM SAHAY VERMA INT COLL BASAUNI -

Scanned by Camscanner

Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner Scanned by CamScanner IRONING OUT THE CREASES: RE-EXAMINING THE CONTOURS OF INVOKING ARTICLE 142(1) OF THE CONSTITUTION Rajat Pradhan* ABSTRACT In the light of the extraordinary and rather frequent invocation of Article 142(1) of the Constitution of India, this note expounds a constructive theory of perusing Article 142(1) by the Supreme Court. The central inquiry seeks to answer the contemporaneous question of whether Article 142 can be invoked to make an order or pass a decree which is inconsistent or in express conflict with the substantive provisions of a statute. To aid this inquiry, cases where the apex court has granted a decree of divorce by mutual consent in exercise of Article 142(1) have been examined extensively. Thus the note also examines the efficacy and indispensible nature of this power in nebulous cases where the provisions of a statute are insufficient for solving contemporary problems or doing complete justice. INTRODUCTION An exemplary provision, Article 142(1) of the Constitution of India envisages that the Supreme Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction may pass such enforceable decree or order as is necessary for doing ‘complete justice’ in any cause or matter pending before it. While the jurisprudence surrounding other provisions of the Constitution has developed manifold, rendering them more concrete and stable interpretations, Article 142(1) is far from tracing this trend. The nature and scope of power contemplated in Article 142(1) has continued to be mooted imaginatively. -

![293 Conservation of Foreign [RAJYA SABHA] Prevention of Smuggling 294 Exchange and Activities (Amdt.) Bill, 1987](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2053/293-conservation-of-foreign-rajya-sabha-prevention-of-smuggling-294-exchange-and-activities-amdt-bill-1987-772053.webp)

293 Conservation of Foreign [RAJYA SABHA] Prevention of Smuggling 294 Exchange and Activities (Amdt.) Bill, 1987

293 Conservation of Foreign [RAJYA SABHA] Prevention of Smuggling 294 Exchange and Activities (Amdt.) Bill, 1987 THE VICE-CHAIRMAN (SHRI JAGESH DESAI): If it is on he record, it is to be expunged. But I have not heard it. (Interruptions) If it is on the record, it will be expunged. Now the House stands adjourned for lunch and will meet at 2.30 P.M. The 'House then adjourned for lunoh at thirty minutes past one of the clock. The House reassembled after lunch at thirtytwo minutes past two of the clock, The Vide-Chairman Shri Jagesh Desai, in the Chir. I. Statutory Resolution seeking dis approval or the conservation of Fo reign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities (Amendment) Ordinance, 1987. II. The Conservation of Foreign Ex change and Prevention of Smuggl ing Activities (Amendment) Bill, 1987—Contd. 295Conservation of Foreign [RAJYA SABHA] Prevention of Smuggling 2 96 Exchange and Activities (Amdt.) Bill, 1987 "The Directorate also identified the telex number in Switzerland as that of the Handlesbank. Moreover, it was able to establish that a Mr. A. K. Jain had indeed stayed in Room No. 1504 of the London Hilton on September 20, 1983 and sent the message. Among the many Finance Ministry officials involved in the investigation were Mr. V. C. Pande, the then Secretary (Revenue), Mr. M. L. Wadhawan, Director-General of Economic Intelligence Bureau Mr. B. V. Kumar, Director, Revenue Intelligence, and others.... 297 Conservation of Foreign [19 AUG. 1987] Prevention of Smuggling 298 Exchange and Activities (Amdt.) bill, 1987 SHRI GHULAM RASOOL MATTO (Jammu and Kashmir): Mr. -

Major Scams in India Since 1947: a Brief Sketch

© 2015 JETIR July 2015, Volume 2, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Major Scams in India since 1947: A Brief Sketch Naveen Kumar Research Scholar Deptt. of History B.R.A.B.U. Muzaffarpur "I would go to the length of giving the whole congress a decent burial, rather than put up with the corruption that is rampant." - Mahatma Gandhi. This was the outburst of Mahatma Gandhi against rampant corruption in Congress ministries formed under 1935 Act in six states in the year 1937.1 The disciples of Gandhi however, ignored his concern over corruption in post-Independence India, when they came to power. Over fifty years of democratic rule has made the people so immune to corruption that they have learnt how to live with the system even though the cancerous growth of this malady may finally kill it. Politicians are fully aware of the corruption and nepotism as the main reasons behind the fall of Roman empire,2 the French Revolution,3 October Revolution in Russia,"4 fall of Chiang Kai-Sheik Government on the mainland of China5 and even the defeat of the mighty Congress party in India.6 But they are not ready to take any lesson from the pages of history. JEEP PURCHASE (1948) The history of corruption in post-Independence India starts with the Jeep scandal in 1948, when a transaction concerning purchase of jeeps for the army needed for Kashmir operation was entered into by V.K.Krishna Menon, the then High Commissioner for India in London with a foreign firm without observing normal procedure.7 Contrary to the demand of the opposition for judicial inquiry as suggested by the Inquiry Committee led by Ananthsayanam Ayyangar, the then Government announced on September 30, 1955 that the Jeep scandal case was closed. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

.BSDI Twelfth Series, Vol. I, No. I LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) First Session (Twelfth Lok Sabha) I Gazettes & Debetes Unit ...... Parliament Library BulldlnO @Q~m ~o. FBr.026 .. ~-- -- (Vol. I contains Nos. I to 8) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI I'ri ce .· Rs. 50. ()() 'VU"".&J:Ia.a.a IL.V .................. ~_ (Engl illl1 v«sian) 'lUeaJay, IIKcb 24, 1998/Chaitra 3, 1920 (Salta) Col.l1ine F« Raad CaltE!1ts/2 (fran &lltcn Salahuddin OWaisi Shri S. S. OWaiai below) 42/28 9/6 (fran below); SHRI ARIF HOfP.MW.D KHAN liIRI ARIF ~D KHAN 10/6 (fran below) j 11. /7,19: 13/3 12/5 (fran below) Delete "an" 13,19 (fran below) CalSSlsnal CalSE!1sual 22/25 hills hails CONTENTS {Twelfth Series. Vol. I. First Session. 199811920 (Seke)J No.2, Tuesday, March 24,1l1li Chain 3,1120 (lab) SUBJECT CoLUMNS MEMBERS SWORN 1-8 f)1:" SPEAKER 8-8 FI::L "'I-fE SPEAKER Shri Atal Biharl Vajpayee •.. 8-14 Shri Sharad Pawar ..• 14-15 Shrl Somnath Chatterjee .. 1~18 Shri Pumo A. Sangma .. 18-17 Kumari Mamata Banerjee .17-18 Shri Ram Vilas Paswan .•. 18 Shri R. Muthiah 19 Shri Mulayam Singh Yadav 19-20 Shri Lalu Prasad ... 21-22 Shri K. Yerrannaidu 22-23 Shri Naveen Patnaik 23 Shri Digvijay Singh .. 23-24 Shri Indrajit Gupta .. 24-25 Sardar Surjit Singh Bamala 2~2e Shri Murasoli Maran 28-28 Shri Shivraj ~. Palll .. ,. 28-29 Shri Madhukar Sirpotdar ... -_ ... 29-31 Shri Sanat Kumar Mandai 31 Shri P.C. Thomas 31-32 Kumari. -

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No

ITI Code ITI Name ITI Category Address State District Phone Number Email Name of FLC Name of Bank Name of FLC Mobile No. Of Landline of Address Manager FLC Manager FLC GR09000145 Karpoori Thakur P VILL POST GANDHI Uttar Ballia 9651744234 karpoorithakur1691 Ballia Central Bank N N Kunwar 9415450332 05498- Haldi Kothi,Ballia Dhanushdhari NAGAR TELMA Pradesh @gmail.com of India 225647 Private ITC - JAMALUDDINPUR DISTT Ballia B GR09000192 Sar Sayed School P OHDARIPUR, Uttar Azamgarh 9026699883 govindazm@gmail. Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. of Technology RAJAPURSIKRAUR, Pradesh com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Private ITC - BEENAPARA, Azamgarh, 276001 Binapara - AZAMGARH Azamgarh GR09000314 Sant Kabir Private P Sant Kabir ITI, Salarpur, Uttar Varanasi 7376470615 [email protected] Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITC - Varanasi Rasulgarh,Varanasi Pradesh m India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Varanasi GR09000426 A.H. Private ITC - P A H ITI SIDHARI Uttar Azamgarh 9919554681 abdulhameeditc@g Azamgarh Union Bank of Shri R A Singh 9415835509 5462246390 TAMSA F.L.C.C. Azamgarh AZAMGARH Pradesh mail.com India Azamgarh, Collectorate, Azamgarh, 276001 GR09001146 Ramnath Munshi P SADAT GHAZIPUR Uttar Ghazipur 9415838111 rmiti2014@rediffm Ghazipur Union Bank of Shri B N R 9415889739 5482226630 UNION BANK OF INDIA Private Itc - Pradesh ail.com India Gupta FLC CENTER Ghazipur DADRIGHAT GHAZIPUR GR09001184 The IETE Private P 248, Uttar Varanasi 9454234449 ietevaranasi@rediff Varanasi Union Bank of Shri Nirmal 9415359661 5422370377 House No: 241G, ITI - Varanasi Maheshpur,Industrial Pradesh mail.com India Kumar Ledhupur, Sarnath, Area Post : Industrial Varanasi GR09001243 Dr. -

Re. Purchase of Submarines 148 SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER

147 Short Duration discussion [ RAJYA SABHA ] re. purchase of submarines 148 SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER: Please don't SHORT DURATION DISCUSSION ON suggest that by shouting you can get rne to, STATEMENT REGARDING ALLEGA. agree to certain things which are not right. HON OF PAYMENT OF COMMISSION You dicuss it with me and I 'am prepared to TO INDIAN AGENTS IN PURCHASE OF discuss it with y°u. SUBMARINES FROM M|S. HDW OF FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY SHRI RAM AWADHESH SINGH: He has rightly put it, what suggestions have been SHRI DIPEN GHOSH (West BengAl): Mr, accepted and what have been rejected? Vice -Chairman, Sir, I beg to raise a discussion on the statement laid on the Table SHRI JAGDISH TYTLER: I am just of the Rajya Sabha by the Minister of answering the question. Two major points Defence on the 26th April, 1988, regarding were raised and I km answering what you said. the allegation of payment of commission to One was, which are.the unions with which the Indian agents in the purchase of submarines discussions took place and I have given the from M|s. HDW of the Federal Republic of names of the unions. Germany. The second point was the serious allegation which you made because you did not go Sir, while raising this discussion I want to through the Bill properly, that it is not time- make it abundantly clear, first of all, that the bound. I would like to tell you that for the generous gesture of the Union Defence tribunal the period is 90 days, for the appelate Minister, Mr. -

(Xiv) (Xiii) CONTENTS Ajit Kumar V. State of Jharkhand & Ors...830

(xiv) CONTENTS Chembur Service Station; Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd. v. ..... 632 Ajit Kumar v. State of Jharkhand & Ors. ..... 830 Childline India Foundation & Anr. v. Allan John Ajit Singh & Anr; Ravindra Pal Singh v. ..... 946 Waters & Ors. ..... 989 Allan John Waters & Ors. ; Childline India Chitrahar Traders; Commr. Of Commercial Foundation & Anr. v. ..... 989 Taxes and Ors. v. ..... 910 Amerika Rai & Ors. v. State of Bihar ..... 176 Commercial Taxes Officer v. M/s. Jalani Enterprises ..... 951 Ashok Kumar Todi v. Kishwar Jahan & Ors. ..... 597 Commr. of Central Excise and Customs; Ashok Tshering Bhutia v. State of Sikkim ..... 242 Mustan Taherbhai (M/s.) v. ..... 353 Asmathunnisa v. State of A.P. represented Commr. of Central Excise, Chandigarh; Hans by the Public Prosecutor, High Court of Steel Rolling Mill etc. (M/s.) v. ..... 841 A.P., Hyderabad & Anr ..... 1116 Commr. of Commercial Taxes and Ors. v. Baskaran (K. K.) v. State Rep. by its Secretary, Chitrahar Traders ..... 910 Tamil Nadu & Ors. ..... 527 Commr. of Police and Ors v. Sandeep Kumar ..... 964 Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd. v. Chembur Service Station ..... 632 Dedicated Freight Corridor Corporation of India v. Subodh Singh & Ors. ..... 1160 Bharat Ratna Indira Gandhi College of Engineering & Others v. State of Delhi Pradesh Regd. Med. Prt. Assn. v. Union Maharashtra & Ors. ..... 1087 of India & Ors. ..... 849 Bombay Environmental Action Group & Ors.; Deputy Superintendent Vigilance Police & Anr.; Krishnadevi Malchand Kamathia & Ors. v. ..... 291 Ramachandran (R.) Nair v. ..... 1054 Brij Pal Bhargava & Ors. v. State of U.P. Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam and Anr. & Ors. ..... 189 v. The Election Commission of India ..... 920 C.I.T., Belgaum & Anr.; Guffic Chem P. -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English .Version)

Nlatla SerIeI, Vol. I. No 4 Tha.... ', DeeemIJer 21. U89 , A..... ' ... 30. I'll (SUa) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English .Version) First Seai.D (Nlntb Lok Sabba) (Yol. I COlJtairu N08. 1 to 9) LOI: SABRA SECRE1'AlUAT NEW DELHI Price, 1 Itt. 6.00 •• , • .' C , '" ".' .1. t; '" CONTENTS [Ninth Series, VoL /, First Session, 198911911 (Saka)] No. 4, Thursday, December 21, 1989/Agrahayana 30, 1911 (Saka) CoLUMNS Members Sworn 1 60 Assent to Bills 1--2 Introduction of Ministers 2-16 Matters Under Rule 377 16-20 (i) Need to convert the narrow gauge railway 16 line between Yelahanka and Bangarpet in Karnataka into bread gauge tine Shri V. Krishna Rao (ii) Need to ban the m~nufadure and sale of 16-17 Ammonium Sulphide in the country Shri Ram Lal Rahi (iii) Need to revise the Scheduled Castes/ 17 Sched uled Tribes list and provide more facilities to backward classes Shri Uttam Rathod (iv) Need to 3et up the proposed project for 18 exploitation of nickel in Sukinda region of Orissa Shri Anadi Charan Das (v) Need to set up full-fledged Doordarshan 18 Kendras in towns having cultural heritage, specially at Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh Shri Anil Shastri (ii) CoLUMNS (vi) Need to set up Purchase Centres in the cotton 18-19 producing districts of Madhya Pradesh Shri Laxmi Narain Pandey (vii) Need for steps to maintain ecological 19 balance in the country Shri Ramashray Prasad Singh (viii) Need to take measures for normalising 19-20 relations between India and Pakistan Prof. Saifuddin Soz (;x) Need to take necessary steps for an amicable 20 solution of the Punjab problem Shri Mandhata Singh Motion of Confidence in the Council of Ministers 20-107 110-131 Shri Vishwanath Pratap Singh 20-21 116-131 Shri A.R. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH MONDAY, THE 13 APRIL, 2015 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 01 TO 49 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 50 TO 50 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 51 TO 65 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 66 TO 84 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 13.04.2015 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 13.04.2015 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE RAJIV SAHAI ENDLAW CONNECTED MATTERS (ADMISSION) 1. LPA 436/2014 UNION OF INDIA ANUJ AGGARWAL,SAQIB,ANGAD CM APPL. 10148/2014 Vs. DR. H.C.SHARATCHANDRA MEHTA CM APPL. 10149/2014 2. LPA 568/2014 UNION OF INDIA ANUJ AGGARWAL CM APPL. 14241/2014 Vs. DR. RAKESH MEHROTRA CM APPL. 14242/2014 WITH LPA 436/2014 3. LPA 569/2014 UNION OF INDIA ANUJ AGGARWAL CM APPL. 14249/2014 Vs. PRADUMAN KUMAR JAIN CM APPL. 14250/2014 4. LPA 570/2014 UNION OF INDIA ANUJ AGGARWAL CM APPL. 14259/2014 Vs. RAJESH KUMAR TYAGI CM APPL. 14260/2014 AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS 5. LPA 52/2015 M/S JOHNSON WATCH COMPANY ABHIJIT BHATTACHARYYA AND CM APPL. 1832/2015 PVT. LTD CHANDRUCHUR BHATTCHARYYA,S K CM APPL. 1834/2015 Vs. DIRECTORATE OF REVENUE DUBEY INTELLIGENCE 6. W.P.(C) 1476/2014 VIKAS SINGH DEEPEIKA KALIA,RAKESH PH Vs. LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR AND MITTAL,ARJUN PANT,GAURANG ORS KANTH,SANJEEV NARULA AT 10.30 AM 7. W.P.(C) 8224/2014 AVTAR SINGH BHADANA CHETAN ANAND,ANURAG Vs. -

Mid-Term Polls

MID-TERM POLLS DEC. 1994 - MARCH 1995 AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial {iilfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of ^- iHastcr '.' '--• of v' i Eibrarp Sc information ^titntt 1994-95 by Miss BABITA \^ /^ Roll No. 94 LSM -14 Enrolement No. Z - 2900 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. S. HASAN ZAMARRUD READER DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 [LS- 1:^70] 2 6 K:.:^ ^99 (p^ DS2670 J^E.diaaiE.d t Q ^V{ij J^oulncj J^jatruii and y\/{ umm i/ CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I - li SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY Vw - v\i 1. PART - ONE INTRODUCTION I'-^8 LIST OF PERIODICALS SCANNED ^^ - IC 2. PART - TWO BIBLIOGRAPHY 11 - ISl 3. PART - THREE INDEX \§^ - $05 **4r****ifr***ifc4r*4r*****ifc**A4rA'**iAri CO ACKNOWLEDGEMENT *••••*••*****•*•*••*•*•••*••*••*•*••*•*•* In this world no task can be accomplished without the help of the creature of this Universe. I am thankrul to the Almighty for providing me shelter against the ruthless showers of crisis. Words seem to be inadequate for the immense appreciation and gratitude I owe to my supervisor, Mr. S. Hasan Zaunarrud, Reader, Department of Library i Information Science. He has been a guiding light in moments of darkness and a piller of strenght in troubled times. I would be failing in my duty if I do not acknowledge the help provided by Mr. Shabahat Husain, Chairman, Deptt.of Lib. & Inf. Sc. A.M.U. His untiring cooperation in providing adequate facilities in the Deptt. and elsewhere for data collection has helped in a long way. I am also indebted to my teachers, Prof.