The Effect of E-Books on Publishers, Libraries, and the First Sale Doctrine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Libraries, Archives and Museums: Trends in Collaboration and Cooperation

International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions IFLA Professional Reports, No. 108 108 Public Libraries, Archives and Museums: Trends in Collaboration and Cooperation Alexandra Yarrow, Barbara Clubb and Jennifer-Lynn Draper for the Public Libraries Section Standing Committee Copyright 2008 International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions Public Libraries, Archives and Museums: Trends in Collaboration and Cooperation / Alexandra Yarrow, Barbara Clubb and Jennifer-Lynn Draper. The Hague, IFLA Headquarters, 2008. – 50p. 30 cm. – (IFLA Professional Reports: 108) ISBN 978-90-77897-28-7 ISSN 0168-1931 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction: Why Collaborate and Cooperate? 5 Project Proposal 6 Research Methods 7 Literature Review 8 Collaborative Programming Community and Heritage Programs 10 Museum/Art Pass Programs 13 Collaborative Electronic Resources Global Initiatives 16 Continental Initiatives 16 National Initiatives 17 Regional and Local Initiatives 20 Joint-use/Integrated Facilities Minimal Integration 25 Selective Integration 27 Full Integration 28 Guide to Collaboration Best Practices 31 A Successful Collaboration, from Start to Finish 32 Creating Collaborative Electronic Resources: Special Considerations 34 Benefits and Risks of Collaboration 35 Risk Management Strategies 36 Conclusion 37 Contributors 38 Acknowledgements 39 Works Consulted 41 1 Executive Summary This report examines the recent trends in collaboration and cooperation between public libraries, archives and museums. In many cases, the shared or similar missions of the institutions reviewed make them ideal partners in collaborative ventures. Different types of collaborative projects are examined, including exhibits, community programs, digital resources and joint-use facilities. Examples come from Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom (UK), as well as from Russia, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Germany, Italy, Spain, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. -

Entire Public Libraries Directory In

October 2021 Directory Local Touch Global Reach https://directory.sailor.lib.md.us/pdf/ Maryland Public Library Directory Table of Contents Allegany County Library System........................................................................................................................1/105 Anne Arundel County Public Library................................................................................................................5/105 Baltimore County Public Library.....................................................................................................................11/105 Calvert Library...................................................................................................................................................17/105 Caroline County Public Library.......................................................................................................................21/105 Carroll County Public Library.........................................................................................................................23/105 Cecil County Public Library.............................................................................................................................27/105 Charles County Public Library.........................................................................................................................31/105 Dorchester County Public Library...................................................................................................................35/105 Eastern -

Ross-Broadway Branch, Denver Public Library National Register

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Ross-Broadway Branch, Denver Public Library Denver, Colorado Name of Property County and State ______________________________________________________________________ 4. National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: entered in the National Register determined eligible for the National Register determined not eligible for the National Register removed from the National Register other (explain:) _____________________ ________________________________________________________________ Signature of the Keeper Date of Action ______________________________________________________________________ 5. Classification Ownership of Property (Check as many boxes as apply.) Private: Public – Local X Public – State Public – Federal Category of Property (Check only one box.) Building(s) X District Site Structure Object Sections 1-6 page 2 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 Ross-Broadway Branch, Denver Public Library Denver, Colorado Name of Property County and State Number of Resources within Property (Do not include previously listed resources in the count) Contributing Noncontributing _____1_______ _______0______ buildings _____________ _____________ sites _____________ _____________ structures _____________ _____________ objects ______1_______ _______0_______ -

DIRECTOR's REPORT June 17, 2021 Strategic Plan Our Mission

DIRECTOR’S REPORT June 17, 2021 Strategic Plan Our Mission: We are “The People’s University,” the center of learning for a diverse and inclusive community. Our Strategic Priorities: 1. Form communities of learning 2. Fight community deficits 3. Ready for the future: CPL 150 4. Cultivate a global perspective 5. Innovate for efficient and sustainable operations PUBLIC SERVICES MAIN LIBRARY SERVICES DURING COVID-19 Due to the public health threat of COVID-19, face coverings and social distancing continue to be required for Library patrons. In addition, time and capacity limits remain in place for TechCentral and branches. PROGRAMS, SERVICES AND EXHIBITS Literature and Ohio Center for the Book Manager Don Boozer hosted a conversation with Derf Backderf on his graphic novel Kent State on May 3rd. The live event and recording have been viewed 68 times. Popular Librarian Judy Daniels and Library Assistant Ricardo Jackson assembled hot lists for books and DVDs for patrons to place holds. Center for Local and Global History Library Assistant Danilo Milich created a May book display, It Is Time to Travel the USA. The display includes travel guides for USA, National Parks, and Civil War sites. Books by Mail Programs Words on Wheels staff mailed out 21 packages containing 36 items to 11 patrons as of May 17th. Homebound Services sent 181 packages to 170 patrons during the month of April. Covid-19 Home Test Distribution Lending Department staff have distributed 343 BinaxNOW COVID-19 Home Test Kits to patrons as of May 18, 2021 at the Main Library Drive—Up Window. -

Library Resources Technical Services

Library Resources & ISSN 0024-2527 Technical Services October 2008 Volume 52, No. 4 OPAC Queries at a Medium-Sized Academic Library Heather L. Moulaison Literature of Acquisitions in Review, 1996–2003 Barbara S. Dunham and Trisha L. Davis How Much are Technical Services Worth? Philip Hider The Association for Library Collections & Technical Services 52 ❘ 4 The Essential Cataloging and Classification Tools on the Web FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Now includes Spanish and French language interfaces! Cataloger’s Classification Desktop Web Now with The most widely used cataloging Full-text display of much quicker documentation resources in an integrated, all LC classification online system—accessible anywhere. schedules & subject Class Schedule navigation! � Look up a rule in AACR2 and then headings. Updated quickly and easily consult the rule’s daily. LC Rule Interpretation (LCRI). � Find LC/Dewey New! � Includes Describing Archives: A Content Standard. correlations—Match LC classification and subject headings to Dewey® classification � Turn to dozens of cataloging publications numbers as found in LC cataloging records. and metadata resource links plus the complete Use in conjunction with OCLC’s WebDewey® MARC 21 documentation. service for perfect accuracy. � Find what you need quickly with the � Search and navigate across all LC classes or enhanced, simplified user interface. the complete LC subject headings. Free trial accounts & annual Free trial accounts & annual subscription prices: subscription prices: Visit www.loc.gov/cds/desktop www.loc.gov/cds/classweb For free trial, complete the order form at Visit www.loc.gov/cds/desktop/OrderForm.html For free trial, complete the order form at www.loc.gov/cds/classweb/application.html AACR2 is the joint property of the American Library Association, the Canadian Library Association, the Chartered Institute of Library and Dewey and WebDewey are registered trademarks of OCLC, Inc. -

Medical Library Association Mosaic '16 Poster Abstracts

Medical Library Association Mosaic ’16 Poster Abstracts Abstracts for the poster sessions are reviewed by members of the Medical Library Association Joint Planning Committee (JPC), and designated JPC members make the final selection of posters to be presented at the annual meeting. 1 Poster Number: 1 Time: Sunday, May 15, 2016, 2:00 PM – 2:55 PM Painting the Bigger Picture: A Health Sciences Library’s Participation in the University Library’s Strategic Planning Process Adele Dobry, Life Sciences Librarian, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA; Vessela Ensberg, Data Curation Analyst, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Libary, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Bethany Myers, AHIP, Research Informationist, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Rikke S. Ogawa, AHIP, Team Leader for Research, Instruction, and Collection Services, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Libary, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA; Bredny Rodriguez, Health & Life Sciences Informationist, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, Los Angeles, CA Objectives: To facilitate health sciences participation in developing a strategic plan for the university library that aligns with the university's core mission and directs the library's focus over the next five years. Methods: The accelerated strategic planning process was planned for summer 2015, to be completed by fall 2015. The process was facilitated by bright spot, a consulting group. Seven initial areas of focus for the library were determined: Library Value and Visibility, Teaching and Learning, Research Process, Information and Resource Access, Relationships Within the Library, and Space Effectiveness. Each area of focus was assigned to a working group of 6-8 library staff members. -

1998 Library Bond Program Annual Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS Strategic Plan Overview Page 1 Executive Summary 3 Library Background 3 Strategic Plan Background 5 Strengths & Opportunities 7 Goals & Activities 10 APPENDICES Library Strengths I Goals, Objectives & Activities II Operational Initiatives III Customer Satisfaction Survey IV Library Technology Plan V Branch Facilities Plan VI Library Bond Program, Annual Report VII STRATEGIC PLAN OVERVIEW "Building on Success," the Los Angeles Public Library's Strategic Plan for 2007 - 2010, is both aspirational and practical; it identifies the library's goals and recommends actions to achieve these goals. Specifically, this strategic plan is designed to help the library accomplish its mission of providing free and easy access to information, ideas, books and technology that enrich, educate and empower every individual in our city's diverse communities. The plan will also serve as a blueprint for building on the library's unprecedented success in providing new facilities, technology, materials and programs that benefit all the people of Los Angeles. Page 1 The firm Dubberly Garcia Associates, Inc. which specializes in library consulting, created the plan with input from library staff, the Board of Library Commissioners, the public, elected officials and other stakeholders. The firm also used information from the library's customer satisfaction survey, strategic technology plan, updated draft facilities plan, and other documents. The plan follows the widely accepted format of the Public Library Association's planning process. The Executive Summary presents an overview of the process and findings, while more detailed information is available in the appendices. The goals in this plan are ambitious, but based on the library's previous successes they are attainable. -

Public Library Websites As Electronic Branches: a Multi- Country Quantitative Evaluation

PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY THE UNIVERSITY OF BORÅS, SWEDEN VOL. 23 NO. 1, MARCH, 2018 Contents | Author index | Subject index | Search | Home Public library Websites as electronic branches: a multi- country quantitative evaluation Diane L. Velasquez and Nina Evans. Introduction. This paper describes the findings of a study of 1517 public library Websites in Australia, Canada, and the United States over a period of four years. These Websites are referred to as ‘electronic branches' of the libraries, thereby extending the definition of physical library branches into the digital realm. The purpose of the research was to investigate the accessibility of public library Websites, the available online resources and whether library staff are available to respond to users' questions and concerns regarding the Website. Method. A quantitative study was conducted, using a spreadsheet protocol to determine if 18 criteria were present on the Websites. General comments about the Websites were also recorded and included in the analysis. Analysis. The quantitative data analysis for the 1517 Websites was done using Excel spreadsheets through formula manipulations. Descriptive statistics are used to report the findings. Results. The data revealed that the Websites of Canadian and USA libraries include more of the criteria than the Australian libraries. Overall many similarities were found between the accessibility of the Websites of the different countries. Conclusion. The study provides exemplars of an electronic branch of a public library and the services it can offer to its community members. These examples can be used to model ideal electronic branch libraries for library staff to improve their Websites. Introduction Public library Websites are often the first, if not the main, point of contact that people have with their local library. -

From Humble Beginnings: a History of the Irving Public Library System

From Humble Beginnings: A History of the Irving Public Library System By Irving Archives, Irving Public Library 801 W. Irving Boulevard, First Floor Irving, Texas 75060 CONTENTS 1941: First Irving Library Opens ........................................................................... 2 An Eye Toward the Future ..................................................................................... 3 The Search for a New Facility ............................................................................... 4 From Private to Public Entity ................................................................................ 5 Growth Continues .................................................................................................. 6 City Archives Established ...................................................................................... 9 Irving Public Library Directors ............................................................................ 10 1 1941: FIRST IRVING LIBRARY OPENS n May 5, 1941, civic activist Esther Hurwitz opened OIrving’s first library in a corner of Louis Blaylock’s furniture store at 126 East First Street. The store was on the south side of the street just east of the intersection of First and Main Streets (First Street is now Irving Boulevard). To provide enough books to open, Mrs. Hurwitz stocked the fledgling library with 50 volumes from her husband’s private collection. Topics ranged from sheep ranching to popular Esther Hurwitz fiction. Soon after the library’s meager beginning, several residents -

ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY Branch Facilities & Operations Plan OCTOBER 2018

ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY Branch Facilities & Operations Plan OCTOBER 2018 In parntership with: TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 01 Introduction Methodology Peer Research Engagement Facilities Assessment Rochester Context 02 Master Plan Framework Opportunity System-Wide Recommendations Branch-Specific Recommendations 03 Implementation Appendix View of Rochester, Outside Sully Branch 2 ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY Libraries are community anchors, the center of civic life and the social backbone of a neighborhood. More than just another building, libraries provide access and opportunity to all: a space where a single mom can take a job training class, a new immigrant can learn English, a low-income family can get help on their tax return and toddlers can attend story time. In Rochester, access to opportunity and information is more important than ever: the median Rochester family income of $31,000 is approximately half the national average ($59,039), and almost one third of Rochester residents live below the poverty line (32%).1 As one of the most deeply loved and historic institutions in the city, the Rochester Public Library (RPL) is uniquely positioned to leverage its branches, programs and services to support neighborhoods, and increase access to opportunity for the city’s most vulnerable communities. The Branch Facilities and Operations Master Plan provides recommendations and strategies that build on the strength of this storied institution and put forth innovative ideas and interventions that position RPL to become one of the most pioneering library systems in the country when it comes to equity. 1(US Census 2016 ACS 5-year estimate) BRANCH FACILITIES + OPERATIONS MASTER PLAN 3 RPL Friends and Foundation, Sully Branch 4 ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY ROCHESTER PUBLIC LIBRARY Branch Facilities & Operations Plan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY RPL’s branch libraries reach over 950,000 The Facilities and Operations Master Plan is guided by the residents annually and hold more than following principles: 6,000 programs. -

Five Year Plan

Arizona LSTA 2018-2022 Five Year Plan Arizona’s Library Services and Technology Act Plan, prepared by the Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records, a Division of the Arizona Department of State, for the Institute of Museum and Library Services Submitted June 30, 2017 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Mission Statement............................................................................................................................ 4 Needs Assessment ............................................................................................................................ 5 2018-2022 Arizona LSTA Goals ........................................................................................................ 8 2018-2022 Arizona LSTA Projects .................................................................................................. 10 Coordination Efforts ....................................................................................................................... 12 Evaluation Plan ............................................................................................................................... 16 Stakeholder Involvement ............................................................................................................... 17 Communication and Public Availability .......................................................................................... 18 Monitoring -

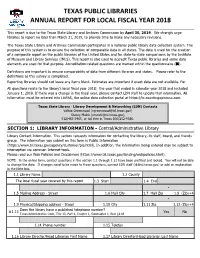

Texas Public Libraries Annual Report for Local Fiscal Year 2018

TEXAS PUBLIC LIBRARIES ANNUAL REPORT FOR LOCAL FISCAL YEAR 2018 This report is due to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission by April 30, 2019. We strongly urge libraries to report no later than March 31, 2019, to provide time to make any necessary revisions. The Texas State Library and Archives Commission participates in a national public library data collection system. The purpose of this system is to ensure the collection of comparable data in all states. The data is used for the creation of a composite report on the public libraries of the United States and for state-to-state comparisons by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). This report is also used to accredit Texas public libraries and some data elements are used for that purpose. Accreditation-related questions are marked within the questionnaire (). Definitions are important to ensure comparability of data from different libraries and states. Please refer to the definitions as this survey is completed. Reporting libraries should not leave any items blank. Estimates are important if exact data are not available. For All questions relate to the library's local fiscal year 2018: the year that ended in calendar year 2018 and included January 1, 2018. If there was a change in the fiscal year, please contact LDN staff to update that information. All information must be entered into LibPAS, the online data collection portal at https://tx.countingopinions.com. Texas State Library - Library Development & Networking (LDN) Contacts Valicia Greenwood ([email protected]) Stacey Malek ([email protected]), 512/463-5465, or toll free in Texas 800/252-9386.