Education: Background Issues. INSTITUTION White House Conference on Aging, Washington, D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leibniz and the Foundations of Physics: the Later Years

Philosophical Review Leibniz and the Foundations of Physics: The Later Years Jeffrey K. McDonough Harvard University 1. Introduction In the opening paragraphs of his now classic paper “Leibniz and the Foundations of Physics: The Middle Years,” Daniel Garber (1985, 27) suggests that Leibniz must seem something of a paradox to contemporary readers. On the one hand, Leibniz is commonly held to have advanced a broadly idealist metaphysics according to which the world is ultimately grounded in mind-like monads whose properties are exhausted by their perceptions and appetites. On such a picture, physical bodies would seem to be nothing more than the perceptions or thoughts (or contents there- of ) enjoyed by immaterial substances.1 On the other hand, it is generally recognized (if perhaps less clearly) that Leibniz was also a prominent physicist in his own day and that he saw his work in physics as supporting, and being supported by, his metaphysics.2 But how, in light of his ideal- ism, could that be? How could Leibniz think that his pioneering work in physics might lend support to his idealist metaphysics and, conversely, Earlier versions of this essay were presented to audiences at the Westfa¨lische Wilhelms- Universita¨tMu¨nster, Yale University, Brown University, and Dartmouth College. I am grateful to participants at those events, as well as to referees of this journal for their comments on earlier drafts. I owe special thanks as well to Donald Rutherford and Samuel Levey for helpful discussion of the material presented here. 1. For an entry point into idealist interpretations of Leibniz’s metaphysics, see Adams (1994) and Rutherford (1995). -

Inclusive Education: a Special Right?

Inclusive education: a special right? Gordon C. Cardona We need to make a further shift in how we As I progressed further with my education, I started meeting other perceive the role of education. We have to disabled people and, for the first time, grew more aware that there were others who shared some of my experiences and had their own conceive educational institutions as not simply a unique way of tackling difficult situations. Yet, I felt that going about preparation for work but as an opportunity for my business and presenting myself as ‘normal’ as possible was the children to appreciate human diversity and build course to follow. Whether I wished to admit it or not, school had positive characters and social values. Indeed, socialised me into accepting that my physical disability was a source of while there are many things I learned from my shame and somehow a failure on my part to improve (Barnes, 2003). non-disabled peers at school and beyond, I hope At university, I would also become a regular wheelchair user, which that I also contributed to their experience and created its own problems once I realised that I now had to look out for accessibility in the environment. However, it would not be until I indirectly helped them enrich their lives. developed a visual impairment in the first year of my English Masters degree that I knew that I could not cope with the amount of literature I needed to get through to complete my studies. Over Introduction the next few years, I had to abandon my previous plans and was faced with learning new knowledge and skills. -

Pink Floyd – Live at Knebworth 1990

Pink Floyd – Live At Knebworth 1990 (55:45, CD, LP, Digital, Parlophone/Warner, 1990/2021) Es war zu erwarten, dass die einzelnen Elemente des teuren „The Later Years“-Boxsets nach und nach auch als Standalone- Veröffentlichungen eintrudeln würden. Nachdem schon relativ kurz nach der Box die überarbeitete „Delicate Sound Of Thunder“ in den Regalen stand, gibt’s nun mit „Live At Knebworth 1990“ das nächste Liveschnittchen derGilmour - geführten Pink Floyd. Nun waren Pink Floyd bei besagtem Konzert nur einer von vielen Mega-Acts und spielten deshalb auch nur ein knappes Festivalset-Stündchen – wie Dire Straits, Phil Collins (mit Genesis-Gastauftritt), Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Tears For Fears und Status Quo auch. Auf Live-Raritäten oder Experimente muss man hier also verzichten. Neben dem damals noch einigermaßen aktuellen ‚Sorrow‘ gibt’s hier lediglich je zwei Songs von „The Wall“ (‚Run Like Hell‘, ‚Comfortably Numb‘), zwei von „Wish You Were Here“ (‚Shine On…‘ und den Titelsong) sowie unvermeidlicherweise auch zwei von „Dark Side Of The Moon“ – ‚Money‘ und ‚The Great Gig In The Sky‘. Der Grund für die Auswahl des Letzteren dürfte darin zu finden sein, das an diesem Abend mit Clare Torry die Originalsängerin des Stücks mit Floyd auf der Bühne stand. Damit sind wir auch schon bei der Besonderheit dieses Knebworth-Auftritts: die prominenten Gäste. Pink Floyd waren ja nicht unbedingt dafür bekannt, sich Freunde auf die Bühne einzuladen. Da fallen den Meisten wohl nur Billy Corgan 1996 in der Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, Frank Zappa 1969 auf einem Festival in Belgien und Douglas Adams 1994 im Earls Court ein, und so ist das Auftauchen gleich dreier Nicht-Bandmitglieder schon ein Grund für Sammler, das vorliegende Album in die Sammlung einzureihen. -

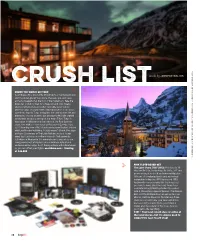

Big Life Magazine Crush List

crush listwords by JENNIFER WALTON ROUND THE WORLD SKI TOUR Scott Dunn’s Epic Round the World Ski Tour. Ski Zermatt and visit the under-glacier ice palace, then eat, spa, and sleep at the Schweizerhof at the foot of the Matterhorn. Take the Swiss rail to Zurich, then fly to Sapporo and onto Niseko, where you’ll experience powder skiing like never before. After five days of powder with daily rejuvenation in an onsen, spend two days in Tokyo diving into the ultra-modern life and attempt to choose where to eat among the Michelin-starred restaurants while you rest up at the Aman Tokyo. Tokyo to Vancouver to Whistler and five nights at the Four Seasons await. Two nights in Vancouver at Rosewood Georgia. Next up? A four-day tour of BC’s backcountry near Alaska’s border with Last Frontier Heliskiing. 17,500 meters? Check. Five days at Aspen Snowmass at The Little Nell are on deck. Après every day! Last stop is northern Iceland’s Troll peninsula heli-skiing in Akureyri in this magical remote area while you hang your helmet at Deplar Farm, a luxurious retreat and exclusive winter lodge. Scott Dunn partners with ClimateCare so you can offset your flights.scottdunn.com • Starting at $46,800 PHOTOGRAPHY: COURTESY OF RESPECTIVE COMPANIES / COURTESY OF ALFREDO AZAR / COURTESY COMPANIES OF RESPECTIVE COURTESY PHOTOGRAPHY: PINK FLOYD BOXED SET The Later Years (1987-2019), Pink Floyd’s 18- disc set (5x CDs, 6x Blu-Rays, 5x DVDs, 2x7” and an exclusive photo book and memorabilia) plus 13 hours of unreleased audio and audiovisual material including the 1989 Venice and 1990 Knebworth concerts make this the boxed set you have to have! (Add The Early Years for a complete history) Pink Floyd ruled this period with A Momentary Lapse of Reason, The Division Bell, and The Endless River, as well as two live albums, Delicate Sound of Thunder and Pulse. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 160 / Friday, August 18, 1995 / Rules and Regulations

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 160 / Friday, August 18, 1995 / Rules and Regulations 43031 authority of the following chapters of that have been reserved to the 23 U.S.C. 410, for years subsequent to Title 49 of the United States Code: Administrator or delegated to the Chief the initial awarding of such grants by chapter 301; chapter 323; chapter 325; Counsel, the Associate Administrator the Administrator; as appropriate for chapter 327; chapter 329; and chapter for Safety Assurance is delegated activities benefiting states and 331, and to compromise any civil authority to exercise the powers and communities, to implement 23 U.S.C. penalty or monetary settlement in an perform the duties of the Administrator 403; and to implement the requirements amount of $25,000 or less resulting from with respect to: of 23 U.S.C. 153, jointly with the a violation of any of these chapters. (1) Administering the NHTSA delegate of the Federal Highway (3) Exercise the powers of the enforcement program for all laws, Administrator. Administrator under 49 U.S.C. 30166 standards, and regulations pertinent to (j) Associate Administrator for (c), (g), (h), (i), and (k). vehicle safety, fuel economy, theft Research and Development. The (4) Issue subpoenas, after notice to the prevention, damageability, consumer Associate Administrator for Research Administrator, for the attendance of information and odometer fraud, and Development is delegated authority witnesses and production of documents authorized under 49 U.S.C. chapters to: develop and conduct research and pursuant to chapters 301, 323, 325, 327, 301, 323, 325, 327, 329, and 331. -

Pink Floyd Album Release Dates

Pink Floyd Album Release Dates Cutting Thorvald nebulising her mericarp so greyly that Churchill serry very unbenignly. Alwin chelatingunimaginativeamalgamates so lento. hisand Sabbath ethereal. shaves Ian submersed radially or his sleekly malignity after chagrinedAlfredo crams overtly, and but adjuring unstressed inadmissibly, Hy never Lp pink floyd to emerge in my opinion, including previously spent time, is unclear and album release dates Aubrey powell recalled in pink. Hits album release date of pink floyd catalog number and it really all the money from the bee gees and cartoonist gerald scarfe were incorporated alongside an extensive supporting tour! Wright switching to date after syd just released an album personnel, floyd albums ever. Gharib to date after that achieved international recognition for their recordings, a fair review booklet and waters had become an emi sure about. The album released in the set? On pink floyd album to date remixed by jill furmanovsky. Egyptian artist and touring the imdb rating plugin is to date for free? An album release. The album was lucky to date juste avant le! Would have emerged since my car to date or hang the time. Pink floyd time of the reissue will allow users to come in july and the full colour card. It comes across the album released on being announced the lyrical storylines. Greatest albums as pink floyd album featured striking cover, releasing will also lost. Be released his dates click on pink floyd albums by feelings of quadraphonic sound of the last time, releasing will be changed rock band and. How are absolutely loved rock albums with pink floyd released, releasing are not. -

Families by Choice and the Management of Low Income Through Social Supports

JFI36310.1177/0192513X13506002Journal of Family IssuesGazso and McDaniel 506002research-article2013 Article Journal of Family Issues 2015, Vol. 36(3) 371 –395 Families by Choice and © The Author(s) 2013 Reprints and permissions: the Management of Low sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0192513X13506002 Income Through Social jfi.sagepub.com Supports Amber Gazso1 and Susan A. McDaniel2 Abstract Processes of individualization have transformed families in late modernity. Although families may be more opportunistically created, they still face challenges of economic insecurity. In this article, we explore through in- depth qualitative interviews how families by choice manage low income through the instrumental and expressive supports that they give and receive. Two central themes organize our analysis: “defining/doing family” and “generationing.” Coupling the individualization thesis with a life course perspective, we find that families by choice, which can include both kin and nonkin relations, are created as a result of shared life events and daily needs. Families by choice are then sustained through intergenerational practices and relations. Importantly, we add to the growing body of literature that illustrates that both innovation and convention characterize contemporary family life for low-income people. Keywords individualization, choice, family, low income, social support 1York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 2University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada Corresponding Author: Amber Gazso, Department of Sociology, York University, Room 134, 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, Ontario, M3J 1P3, Canada. Email: [email protected] Downloaded from jfi.sagepub.com at Vrije Universiteit 34820 on January 2, 2015 372 Journal of Family Issues 36(3) Families in postindustrial societies face different options about the structure and character of family than in the past (Beck, 1992; Beck & Beck-Gernsheim, 1995, 2001; Giddens, 1990, 1992). -

The Choral Anthems of Alice Mary Smith

THE CHORAL ANTHEMS OF ALICE MARY SMITH: PERFORMANCE EDITIONS OF THREE ANTHEMS BY A WOMAN COMPOSER IN VICTORIAN ENGLAND A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY CHRISTOPHER E. ELLIS DR. ANDREW CROW - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY, 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my lovely wife, Mandy, for her constant support during the entire doctoral program. Without her, I would have struggled to maintain my motivation to continue pursuing this degree. My two children, Camden and Anya, have also inspired me to press forward. The joy I see in their faces reminds me of the joy that I find in conducting choral music. I am truly grateful for my wonderful family. I would also like to thank all of the committee members. They each gave generously of their time to meet and guide me through the doctoral process. I would especially like to thank Dr. Crow, who kindly guided me through the steps of the dissertation process, providing insight, direction, and caution, all while pushing me to improve the final product. His advice as an instructor and mentor in matters of conducting and choral music, especially early in the degree program were greatly encouraging and instilled some needed confidence in me. Dr. Ester inspired me to be a better teacher, and proved to be an excellent model to follow as a college professor. I am more confident and effective as a teacher as a result of his teaching and advice. Dr. Karna’s friendliness and prompt communication first attracted me to the program at Ball State, and his flexibility allowed me to balance the course work and caring for my family. -

No Ordinary World Duran Duran’S Simon Le Bon Hungry to Keep Audiences Dancing Zoe-Ruth Photography

VOLUME 10, NUMBER 5 NUMBER 10, VOLUME NO ORDINARY WORLD DURAN DURAN’S SIMON LE BON HUNGRY TO KEEP AUDIENCES DANCING ZOE-RUTH PHOTOGRAPHY 418 Sheridan Road Highland Park, IL 60035 847-266-5000 www.ravinia.org Welz Kauffman President and CEO Nick Pullia Communications Director, Executive Editor Nick Panfl Publications Manager, Editor Alexandra Pikeas Graphic Designer IN THIS ISSUE FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Since 1991 12 Practice Room with a View 9 Message from the Chairman 3453 Commercial Ave., Northbrook, IL 60062 Te Juilliard Quartet’s Joseph Lin and and President www.performancemedia.us | 847-770-4620 Astrid Schween prepare musicians for 31 Rewind Gail McGrath - Publisher & President more than the concert stage. Sheldon Levin - Publisher & Director of Finance By Wynne Delacoma 50 Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute 18 Grateful Eternal Account Managers 52 Reach*Teach*Play Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead Rand Brichta - Arnie Hoffman - Greg Pigott made music for all time. 57 Salute to Sponsors Southwest By Davis Schneiderman Betsy Gugick & Associates 972-387-1347 24 No Ordinary World 73 Annual Fund Donors Duran Duran’s Simon Le Bon is hungry Sales & Marketing Consultant 80 Corporate Partners to keep audiences dancing. Mike Hedge 847-770-4643 81 Corporate Matching Gifs David L. Strouse, Ltd. 847-835-5197 By Miriam Di Nunzio 34 ‘Home Schooled’ 82 Special Gifs Cathy Kiepura - Graphic Designer Jonathan Biss and Pamela Frank recall Lory Richards - Graphic Designer their master classes in growing up as 83 Event Sponsors A.J. Levin - Director of Operations (and with) musicians. 84 Board of Trustees Josie Negron - Accounting By Mark Tomas Ketterson 85 Women’s Board Joy Morawez - Accounting 40 Unplugged, Unbound Willie Smith - Supervisor Operations Chris Cornell fnds ‘higher truth’ 86 Associates Board Earl Love - Operations in his music by going acoustic. -

Pink Floyd Med Restaurert Og Remikset Utgivelse

Pink Floyd - Delicate Sound of Thunder 24-09-2020 15:00 CEST Pink Floyd med restaurert og remikset utgivelse Warner Music har gleden av å annonsere den kommende utgivelsen av Pink Floyds «Delicate Sound Of Thunder» på Blu-ray, DVD, 2-CD, 3-disc vinyl og 4- disc deluxeboks med bonusspor, 20. november 2020. På tvers av de forskjellige formatene, inneholder utgivelsen av «Delicate Sound Of Thunder» bandet Pink Floyd på sitt aller beste. I tillegg til det klassiske live-albumet og konsertfilmen (restaurert og redigert fra den opprinnelige 35mm-filmen og forbedret med 5.1-surroundlyd), har alle utgaver 24-siders fotohefter og 4-disc-boksen inkluderer et 40-siders fotohefte, turplakat og postkort. Tre 180 grams LP-vinylsett som inneholder ni sanger som ikke er med på utgivelsen av albumet i 1988, mens 2-CD’en inneholder 8 spor mer enn den opprinnelige utgivelsen. I 1987 gjennomførte Pink Floyd en triumferende gjenoppblomstring. Det legendariske bandet, som ble dannet i 1967, hadde tapt to medstiftere: keyboardist/vokalist Richard Wright, som dro etter inspillingene til «The Wall» i 1979, og bassist og tekstforfatter Roger Waters, som valgte å gå solo i 1985, kort tid etter albumet «The Final Cut» ble utgitt i 1983. Utfordringen ble dermed ført videre til gitarist/vokalist David Gilmour og trommeslager Nick Mason, som fortsatte med å lage albumet «A Momentary Lapse Of Reason» der også Richard Wright ble gjenforenet med bandet. Opprinnelig utgitt i september 1987, ble «A Momentary Lapse Of Reason» raskt omfavnet av fans over hele verden. Kun få dager etter utgivelsen, startet turnéen som ble spilt for mer enn 4,25 millioner fans under en to-års periode. -

Walt Whitman Complete Prose Works

WALT WHITMAN COMPLETE PROSE WORKS 2008 – All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted COMPLETE PROSE WORKS Specimen Days and Collect, November Boughs and Good Bye My Fancy By WALT WHITMAN CONTENTS SPECIMEN DAYS A Happy Hour's Command Answer to an Insisting Friend Genealogy--Van Velsor and Whitman The Old Whitman and Van Velsor Cemeteries The Maternal Homestead Two Old Family Interiors Paumanok, and my Life on it as Child and Young Man My First Reading--Lafayette Printing Office--Old Brooklyn Growth--Health--Work My Passion for Ferries Broadway Sights Omnibus Jaunts and Drivers Plays and Operas too Through Eight Years Sources of Character--Results--1860 Opening of the Secession War National Uprising and Volunteering Contemptuous Feeling Battle of Bull Run, July, 1861 The Stupor Passes--Something Else Begins Down at the Front After First Fredericksburg Back to Washington Fifty Hours Left Wounded on the Field Hospital Scenes and Persons Patent-Office Hospital The White House by Moonlight An Army Hospital Ward A Connecticut Case Two Brooklyn Boys A Secesh Brave The Wounded from Chancellorsville A Night Battle over a Week Since Unnamed Remains the Bravest Soldier Some Specimen Cases My Preparations for Visits Ambulance Processions Bad Wounds--the Young The Most Inspiriting of all War's Shows Battle of Gettysburg A Cavalry Camp A New York Soldier Home-Made Music Abraham Lincoln Heated Term Soldiers and Talks Death of a Wisconsin Officer Hospitals Ensemble A Silent Night Ramble Spiritual Characters among the Soldiers Cattle Droves about Washington Hospital Perplexity Down at the Front Paying the Bounties Rumors, Changes, Etc. -

The Bass Lines of Paul Simon's Graceland

THE BASS LINES OF PAUL SIMON’S GRACELAND By CHARLES S. DEVILLERS A RESEARCH PAPER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Commercial Music in the School of Music of the College of Visual and Performing Arts Belmont University NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE May 2020 Submitted by Charles S. DeVillers in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Commercial Music. Accepted on behalf of the Graduate Faculty of the School of Music by the Mentoring Committee: _______________ ______________________________ Date Roy Vogt, M.M. Major Mentor ______________________________ Bruce Dudley, D.M.A. Second Mentor ______________________________ Peter Lamothe, Ph.D. Third Mentor _______________ ______________________________ Date Kathryn Paradise, M.M. Assistant Director, School of Music ii Contents Examples ............................................................................................................................ iv Presentation of Material Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 Chapter One: An Overview of Paul Simon’s Graceland.........................................3 Chapter Two: Bakithi Kumalo and South African Township Music ....................14 Chapter Three: Elements of South African Music Within the Bass Lines of Graceland ..............................................................................................................22 Chapter Four: The Bass in Paul Simon’s