Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feral Experimental Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

18 July–30 August 2014 UNSW Galleries UNSW Australia Art & Design Sydney National Institute for Experimental Arts UNSW Art & Design 2014 ©2014 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the permission of the authors. ISBN: 978-0-9925491-0-7 2 3 Contents Introduction If We Never Meet Again, Noam Toran (2010) 6 Dingo Logic: Feral Experimental and New Design Tinking, Katherine Moline Te Imaginary App, Paul D. Miller (aka DJ Spooky) and Svitlana Matviyenko (2012-2014) Kindred Spirits, G-Motiv, Susana Cámara Leret (2013) Feral Experimental Exhibition Te Machine to be Another, BeAnotherLab: Philippe Bertrand, Christian Cherene, Daniel González Franco, Daanish Masood, Mate Roel, Arthur Tres 12 List of Works (2013–2014) Avena+ Test Bed — Agricultural Printing and Altered Landscapes, Benedikt Groß (2013) Te Phenology Clock, Natalie Jeremijenko, Tega Brain, Drew Hornbein and Tiago de Mello Bueno (2014) Circus Oz Living Archive, David Carlin, Lukman Iwan, Adrian Miles, Reuben Stanton, Peta Tait, James Tom, Laurene Vaughan, Jeremy Yuille (2011–2014) Run that Town: A strategy game with a twist, Te Australian Bureau of Statistics, Leo Burnett Sydney, and Millipede Creative Development, Canberra and Community Centred Innovation: Co-designing for disaster preparedness, Yoko Sydney (2013) Akama (2009–2014) Sensitive Aunt Provotype, Laurens Boer and Jared Donovan (2012) Design-Antropologisk Innovations Model / Te Design Anthropological Innovation Model (DAIM), Joachim Halse, Eva Brandt, Brendon Clark and Tomas Binder Veloscape v.5, Volker Kuchelmeister (2014) (2008-2010) 50 Exhibition Biographies Double Fountain: Schemata for Disconnected-Connected Bodies [afer a water- clock design by the Arab engineer Al-Jazari 1136–1206], Julie Louise Bacon and 74 Acknowledgements James Geurts (2014) Emotiv Epoc+ and Emotiv Insight, Emotiv Inc. -

Videodiskothek Sunrise Playlist: Pink Floyd Garten Party – 26.08.2017

Videodiskothek Sunrise Playlist: Pink Floyd Garten Party – 26.08.2017 Quelle: http://www.videodiskothek.com The Orb + David Gilmour - Metallic Spheres (audio only) Alan Parsons + David Gilmour - Return To Tunguska (audio only) Pink Floyd - The Dark Side Of The Moon (full album) Roger Waters - Wait For Her David Gilmour - Rattle That Lock Pink Floyd - Another Brick In The Wall Pink Floyd - Marooned Pink Floyd - On The Turning Away Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here (live) Pink Floyd - The Gunners Dream Pink Floyd - The Final Cut Pink Floyd - Not Now John Pink Floyd - The Fletcher Memorial Home Pink Floyd - Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun Pink Floyd - High Hopes Pink Floyd - The Endless River (full album) [LASERSHOW] Pink Floyd - Cluster One Pink Floyd - What Do You Want From Me Pink Floyd - Astronomy Domine Pink Floyd - Childhood's End Pink Floyd - Goodbye Blue Sky Pink Floyd - One Slip Pink Floyd - Take It Back Pink Floyd - Welcome To The Machine Pink Floyd - Pigs On The Wing Roger Waters - Dogs (live) David Gilmour - Faces Of Stone Richard Wright + David Gilmour - Breakthrough (live) Pink Floyd - A Great Day For Freedom Pink Floyd - Arnold Lane Pink Floyd - Mother Pink Floyd - Anisina Pink Floyd - Keep Talking (live) Pink Floyd - Hey You Pink Floyd - Run Like Hell (live) Pink Floyd - One Of These Days Pink Floyd - Echoes (quad mix) [LASERSHOW] Pink Floyd - Shine On You Crazy Diamond Pink Floyd - Wish You Were Here Pink Floyd - Signs Of Life Pink Floyd - Learning To Fly David Gilmour - In Any Tongue Roger Waters - Perfect Sense (live) David Gilmour - Murder Roger Waters - The Last Refugee Pink Floyd - Coming Back To Life (live) Pink Floyd - See Emily Play Pink Floyd - Sorrow (live) Roger Waters - Amused To Death (live) Pink Floyd - Wearing The Inside Out Pink Floyd - Comfortably Numb. -

Multilinear Euo Lution: Eaolution and Process'

'1. Multilinear Euolution: Eaolution and Process' THEMEANING Of EVOLUIION Cultural evolution, although long an unfashionable concept, has commanded renewed interest in the last two decades. This interest does not indicate any seriousreconsideration of the particular historical reconstructions of the nineteenth-century evolutionists, for thesc were quite thoroughly discredited on empirical grounds. It arises from the potential methodological importance of cultural evolution for con- temporary research, from the implications of its scientific objectives, its taxonomic procedures, and its conceptualization of historical change and cultural causality. An appraisal of cultural evolution, therefore, must be concerned with definitions and meanings. But I do not wish to engage in semantics. I shall attempt to show that if certain distinc- tions in the concept of evolution are made, it is evident that certain methodological propositions find fairly wide acceptance today. In order to clear the ground, it is necessaryfirst to consider the meaning of cultural evolution in relation to biological evolution, for there is a wide tendency to consider the former as an extension of, I This chapter is adapted lrom "Evolution and Process," in Anthropology Today: An Encyclopedic Inaentory, ed. A. L. Kroeber (University of Chicago Press, 1953), pp. 313-26, by courtesy of The University of Chicago Press. l1 12 THEoR'- oF cuLTURE cIIANGE and thercfore analogousto, the latter. There is, of course,a relation- ship betrveen biological and cultural evolution in that a minimal dcvclopment of the Hominidae was a prccondition of culture. But cultural cvolution is an extension of biological evolution only in a chronological sense (Huxley, 1952). The nature of the cvolutionary schemesand of the devclopmental processesdiffers profoundly in. -

Ukraine's Structural Pension Reforms and Women's Ageing Experiences

Ukraine’s Structural Pension Reforms and Women’s Ageing Experiences A Research Paper written by: Oleksandra Pravednyk Ukraine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for obtaining the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES Major: Social Policy for Development (SPD) Members of the Examining Committee: Amrita Chhachhi Mahmoud Messkoub Word Count: 17,225 The Hague, The Netherlands December 2016 1 2 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 5 LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................ 11 ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................. 21 PENSION SYSTEM IN UKRAINE ........................................................................ 29 CONTEXT ............................................................................................................... 34 RESULTS AND ANALYSIS .................................................................................. 41 CONCLUSION ........................................................................................................ 56 BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................................................................................... 57 Annex I .................................................................................................................... -

Leibniz and the Foundations of Physics: the Later Years

Philosophical Review Leibniz and the Foundations of Physics: The Later Years Jeffrey K. McDonough Harvard University 1. Introduction In the opening paragraphs of his now classic paper “Leibniz and the Foundations of Physics: The Middle Years,” Daniel Garber (1985, 27) suggests that Leibniz must seem something of a paradox to contemporary readers. On the one hand, Leibniz is commonly held to have advanced a broadly idealist metaphysics according to which the world is ultimately grounded in mind-like monads whose properties are exhausted by their perceptions and appetites. On such a picture, physical bodies would seem to be nothing more than the perceptions or thoughts (or contents there- of ) enjoyed by immaterial substances.1 On the other hand, it is generally recognized (if perhaps less clearly) that Leibniz was also a prominent physicist in his own day and that he saw his work in physics as supporting, and being supported by, his metaphysics.2 But how, in light of his ideal- ism, could that be? How could Leibniz think that his pioneering work in physics might lend support to his idealist metaphysics and, conversely, Earlier versions of this essay were presented to audiences at the Westfa¨lische Wilhelms- Universita¨tMu¨nster, Yale University, Brown University, and Dartmouth College. I am grateful to participants at those events, as well as to referees of this journal for their comments on earlier drafts. I owe special thanks as well to Donald Rutherford and Samuel Levey for helpful discussion of the material presented here. 1. For an entry point into idealist interpretations of Leibniz’s metaphysics, see Adams (1994) and Rutherford (1995). -

Inclusive Education: a Special Right?

Inclusive education: a special right? Gordon C. Cardona We need to make a further shift in how we As I progressed further with my education, I started meeting other perceive the role of education. We have to disabled people and, for the first time, grew more aware that there were others who shared some of my experiences and had their own conceive educational institutions as not simply a unique way of tackling difficult situations. Yet, I felt that going about preparation for work but as an opportunity for my business and presenting myself as ‘normal’ as possible was the children to appreciate human diversity and build course to follow. Whether I wished to admit it or not, school had positive characters and social values. Indeed, socialised me into accepting that my physical disability was a source of while there are many things I learned from my shame and somehow a failure on my part to improve (Barnes, 2003). non-disabled peers at school and beyond, I hope At university, I would also become a regular wheelchair user, which that I also contributed to their experience and created its own problems once I realised that I now had to look out for accessibility in the environment. However, it would not be until I indirectly helped them enrich their lives. developed a visual impairment in the first year of my English Masters degree that I knew that I could not cope with the amount of literature I needed to get through to complete my studies. Over Introduction the next few years, I had to abandon my previous plans and was faced with learning new knowledge and skills. -

Pink Floyd – Live at Knebworth 1990

Pink Floyd – Live At Knebworth 1990 (55:45, CD, LP, Digital, Parlophone/Warner, 1990/2021) Es war zu erwarten, dass die einzelnen Elemente des teuren „The Later Years“-Boxsets nach und nach auch als Standalone- Veröffentlichungen eintrudeln würden. Nachdem schon relativ kurz nach der Box die überarbeitete „Delicate Sound Of Thunder“ in den Regalen stand, gibt’s nun mit „Live At Knebworth 1990“ das nächste Liveschnittchen derGilmour - geführten Pink Floyd. Nun waren Pink Floyd bei besagtem Konzert nur einer von vielen Mega-Acts und spielten deshalb auch nur ein knappes Festivalset-Stündchen – wie Dire Straits, Phil Collins (mit Genesis-Gastauftritt), Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Tears For Fears und Status Quo auch. Auf Live-Raritäten oder Experimente muss man hier also verzichten. Neben dem damals noch einigermaßen aktuellen ‚Sorrow‘ gibt’s hier lediglich je zwei Songs von „The Wall“ (‚Run Like Hell‘, ‚Comfortably Numb‘), zwei von „Wish You Were Here“ (‚Shine On…‘ und den Titelsong) sowie unvermeidlicherweise auch zwei von „Dark Side Of The Moon“ – ‚Money‘ und ‚The Great Gig In The Sky‘. Der Grund für die Auswahl des Letzteren dürfte darin zu finden sein, das an diesem Abend mit Clare Torry die Originalsängerin des Stücks mit Floyd auf der Bühne stand. Damit sind wir auch schon bei der Besonderheit dieses Knebworth-Auftritts: die prominenten Gäste. Pink Floyd waren ja nicht unbedingt dafür bekannt, sich Freunde auf die Bühne einzuladen. Da fallen den Meisten wohl nur Billy Corgan 1996 in der Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, Frank Zappa 1969 auf einem Festival in Belgien und Douglas Adams 1994 im Earls Court ein, und so ist das Auftauchen gleich dreier Nicht-Bandmitglieder schon ein Grund für Sammler, das vorliegende Album in die Sammlung einzureihen. -

Big Life Magazine Crush List

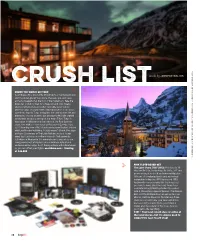

crush listwords by JENNIFER WALTON ROUND THE WORLD SKI TOUR Scott Dunn’s Epic Round the World Ski Tour. Ski Zermatt and visit the under-glacier ice palace, then eat, spa, and sleep at the Schweizerhof at the foot of the Matterhorn. Take the Swiss rail to Zurich, then fly to Sapporo and onto Niseko, where you’ll experience powder skiing like never before. After five days of powder with daily rejuvenation in an onsen, spend two days in Tokyo diving into the ultra-modern life and attempt to choose where to eat among the Michelin-starred restaurants while you rest up at the Aman Tokyo. Tokyo to Vancouver to Whistler and five nights at the Four Seasons await. Two nights in Vancouver at Rosewood Georgia. Next up? A four-day tour of BC’s backcountry near Alaska’s border with Last Frontier Heliskiing. 17,500 meters? Check. Five days at Aspen Snowmass at The Little Nell are on deck. Après every day! Last stop is northern Iceland’s Troll peninsula heli-skiing in Akureyri in this magical remote area while you hang your helmet at Deplar Farm, a luxurious retreat and exclusive winter lodge. Scott Dunn partners with ClimateCare so you can offset your flights.scottdunn.com • Starting at $46,800 PHOTOGRAPHY: COURTESY OF RESPECTIVE COMPANIES / COURTESY OF ALFREDO AZAR / COURTESY COMPANIES OF RESPECTIVE COURTESY PHOTOGRAPHY: PINK FLOYD BOXED SET The Later Years (1987-2019), Pink Floyd’s 18- disc set (5x CDs, 6x Blu-Rays, 5x DVDs, 2x7” and an exclusive photo book and memorabilia) plus 13 hours of unreleased audio and audiovisual material including the 1989 Venice and 1990 Knebworth concerts make this the boxed set you have to have! (Add The Early Years for a complete history) Pink Floyd ruled this period with A Momentary Lapse of Reason, The Division Bell, and The Endless River, as well as two live albums, Delicate Sound of Thunder and Pulse. -

Leslie White (1900-1975)

Neoevolutionism Leslie White Julian Steward Neoevolutionism • 20th century evolutionists proposed a series of explicit, scientific laws liking cultural change to different spheres of material existence. • Although clearly drawing upon ideas of Marx and Engels, American anthropologists could not emphasize Marxist ideas due to reactionary politics. • Instead they emphasized connections to Tylor and Morgan. Neoevolutionism • Resurgence of evolutionism was much more apparent in U.S. than in Britain. • Idea of looking for systematic cultural changes through time fit in better with American anthropology because of its inclusion of archaeology. • Most important contribution was concern with the causes of change rather than mere historical reconstructions. • Changes in modes of production have consequences for other arenas of culture. • Material factors given causal priority Leslie White (1900-1975) • Personality and Culture 1925 • A Problem in Kinship Terminology 1939 • The Pueblo of Santa Ana 1942 • Energy and the Evolution of Culture 1943 • Diffusion Versus Evolution: An Anti- evolutionist Fallacy 1945 • The Expansion of the Scope of Science 1947 • Evolutionism in Cultural Anthropology: A Rejoinder 1947 • The Science of Culture 1949 • The Evolution of Culture 1959 • The Ethnology and Ethnography of Franz Boas 1963 • The Concept of Culture 1973 Leslie White • Ph.D. dissertation in 1927 on Medicine Societies of the Southwest from University of Chicago. • Taught by Edward Sapir. • Taught at University of Buffalo & University of Michigan. • Students included Marshall Sahlins and Elman Service. • A converted Boasian who went back to Morgan’s ideas of evolutionism after reading League of the Iroquois. • Culture is based upon symbols and uniquely human ability to symbolize. • White calls science of culture "culturology" • Claims that "culture grows out of culture" • For White, culture cannot be explained biologically or psychologically, but only in terms of itself. -

SELF-SYNCHRONIZING MACHINES. [10Th April

62 ROSENBERG: SELF-SYNCHRONIZING MACHINES. [10th April, SELF-SYNCHRONIZING MACHINES. By DR. E. ROSENBERG, Member. (Paper first received 29th January, and in final form 10th March, 1913 ; read before THE INSTITUTION 10th April, before the MANCHESTER LOCAL SECTION 1st April, and before the BIRMINGHAM LOCAL SECTION gtli April SYNOPSIS. Scope of the Synchronous Motor. Self-starting Synchronous Motors. (a) Modified induction motor. (b) Salient pole motor. Pulling into Synchronism. (a) Field excited. (b) Field unexcited. Self-starting Rotary Converters. Self-synchronizing using Starting Motor. Voltage Distribution between Synchronous Machine and series-connected Starting Motor. This paper was primarily intended to describe a new method of starting synchronous machines; but as self-starting synchronous machines may be somewhat unfamiliar to many engineers—although such machines date back far into the last century—it was thought advisable also to explain the known methods of starting, to illustrate their working by some test results, and to publish in this connection a short theoretical investigation on " pulling into synchronism." SCOPE OF THE SYNCHRONOUS MOTOR. Synchronous motors have two advantages over induction motors : (1) they do not require magnetizing current from the line ; (2) they can be designed, and practically must be designed, with a bigger air- gap than induction motors. Their peculiarity of running at an absolutely fixed speed for a given frequency is only in a few cases a real advantage, and more often a serious drawback. The necessity of continuous-current excitation, and of the proper adjustment of the same, complicates the machine, and however much the starting apparatus may have been improved, it is certainly more complicated than that of a slip-ring or squirrel-cage motor. -

47 of BYRD's MEN MAROONED on ICE Poimcuissie FRANCE's

ILf OBOULATION f o r ' « M< • f Doeombor, 19M QweiaUy foi* o a t Member of the Audit alghtt Suadi^ with proftaMir B un M of Orenlotloiie. ■gut - “ VOL. Lin., NO. 100. (daaalfled Adrertialac oa Page 10.) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JANUARY 27,1934. (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THKERCBJm 47 OF BYRD’S MEN U. S, Extends A Diplomatic Hand To Cuba HVE THOUSAND FRANCE’S PREMIER MAROONED ON ICE \V^ \ S\ i^sv. \ ATRINKWATCH AND HIS CABINET <$>* ICE C p i V A L Whole Front of Bay Flooring FAMOUS ACTRESS M w Perfect Night, Perfect Ice TO RESIGN TODAY Cmmblmg and Ship Un- •<$> FEARS KIDNAPERS Aid First Fancy Dress able to Get Near, Fear for Bayonue Bank Siandal Cause Fete at Center Springs; GUNMEN STEAL Men’s Safety. Mary Pickford TeDs Boston of Downfall— Riots Mark Experts Give Fine Show. POUCEGEARAT Police She Is Being Trail Eyery Session of Chamber Bay of Whales, Anarctic, Jan. 27. — (Via Mackay radio)— (A P )—^Rear Five thoussmd people from Hart BOSTomiDBrr of Deputies — Hernotnur Admiral Richard E. Byrd expressed ed; Is Given a Guard. ford, Springfield and several near apprehension today for the safety by cities and from Manchester at DaladierMay Head New of Pressure Camp and 43 men of the tended the first costume ice party Raid Auto Show During second Antarctic expedition, men Falmouth, Mass., Jan. 27.— (A P ) on Center Springs rink last night. marooned there by disintegration of — The home of Fulton Oursler, play ’The Ice was perfect, so was the Goyemment the vast ice shelf covering the bay. -

How to Age Less • Look Great • Live Longer • Get More Testimonials

FASTSLOW LIV NG AGEING HOW TO AGE LESS • LOOK GREAT • LIVE LONGER • GET MORE TESTIMONIALS “The human body is not built for an unlimited lifespan. Yet there are many ways in which we can improve and prolong our health. ‘Fast Living, Slow Ageing’ is all about embracing those opportunities.” Robin Holliday, author of ‘Understanding Ageing’ and ‘Ageing: The Paradox of Life’ “Today in Australia, we eat too much and move too little. But it is our future that will carry the cost. Our current ‘fast’ lifestyles will have their greatest impact on our prospects for healthy ageing. This book highlights many of the opportunities we all have to make a diference to our outlook, at a personal and social level.” Professor Stephen Leeder, AO, Director of the Menzies Centre for Health Policy, which leads policy analysis of healthcare “Healthy ageing can’t be found in a single supplement, diet or lifestyle change. It takes an integrated approach across a number of key areas that complement to slowly build and maintain our health. ‘Fast Living, Slow Ageing’ shows how it is possible to practically develop these kind of holistic techniques and take control of our future.” Professor Marc Cohen, MBBS (Hons), PhD (TCM), PhD (Elec Eng), BMed Sci (Hons), FAMAC, FICAE, Professor, founder of www.thebigwell.com “SLOW is about discovering that everything we do has a knock-on efect, that even our smallest choices can reshape the big picture. Understanding this can help us live more healthily, more fully and maybe even longer too.” Carl Honoré, author of ‘In Praise of Slow’ “We all know about the dangers of fast food.