Vortex Formation in the Tethered Flight of the Peacock Butterfly Inachis 10 L. (Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae) and Some Aspects of Insect Flight Evolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying the Garden Butterflies of the Upper Thames Region Summer Very Top Tip

Identifying the Garden Butterflies of the Upper Thames Region Summer Very Top Tip Identifying butterflies very often depends on details at the wing edges (including the margins), but this is less helpful with some summer species. Note the basic ground colour to get a clue to the family and then look at wing edges and eye spots for further identification. The butterfly’s size and actions, plus location and time of year are all helpful . Butterflies that deliberately chase others (and large flies etc.) are usually male. Butterflies spending a long time flying around and investigating an individual plant are probably female. Peacock Red Admiral & Painted Lady The wing tips of PL separate it from Fritillaries Red Admiral & Painted Lady Comma Painted Lady Small Tortoiseshell Speckled Wood Chequered margins andSpeckled large blotches of yellowy creamWood on chocolate background. Often seen basking in patches of sun in areas of dappled sunlight. Rarely visits flowers. Comma Small Tort Wavy outline Blue-ish margin Peacock Speckled Wood Usually less contrasty than the rest with various eyespots and With a straighter border between Blue-ish margin prominent veins Brimstone and Clouded Yellow B has pointy wing tips CY has a white centre to brown spot on hind wing Black tips on upper visible in flight. Small White m and Large White f Very small amounts of dark scales on leading edge of forewing of Small W rarely turn around tip, but Large has large L of black scales that extend half way down the wing Female Brimstone and Green-veined White Brimstone fem looks white in flight but slightly greenish-yellow when settled. -

Attempted Interspecific Mating by an Arctic Skipper with a European Skipper

INSECTS ATTEMPTED INTERSPECIFIC MATING BY AN ARCTIC SKIPPER WITH A EUROPEAN SKIPPER Peter Taylor P.O. Box 597, Pinawa, MB R0E 1L0, E-mail: <[email protected]> At about 15:15 h on 3 July 2011, focused, shows the Arctic skipper’s I observed a prolonged pursuit of a abdomen curved sideways in a J-shape, European skipper (Thymelicus lineola) almost touching the tip of the European by an Arctic skipper (Carterocephalus skipper’s abdomen in what appears palaemon). This took place along Alice to be a copulation attempt (Fig. 1d). Chambers Trail (50.17° N, 95.92° W) Frequent short flights by the European near the Pinawa Channel, a small branch skipper may have been an attempt to of the Winnipeg River in southeastern discourage its suitor – a known tactic used Manitoba. This secluded section of the by unreceptive female butterflies1 – but it Trans-Canada Trail passes through may simply have been disturbed by my moist, mature mixed-wood forest with close approach. Otherwise, the European small, sunlit openings that offer many skipper showed no obvious response to opportunities to observe and photograph the Arctic skipper’s advances. butterflies and dragonflies during the summer months. These two species are classified in separate subfamilies (Arctic skipper in The skipper pursuit continued for Heteropterinae, European skipper in about four minutes, and I obtained Hesperiinae). Both species are only 14 photographs, four of which are slightly dimorphic, and while the Arctic reproduced here (Fig. 1, see inside skipper’s behaviour indicates it was a front cover). The behaviour appeared male, it is not certain that the European to be attempted courtship, rather than a skipper was a female. -

10Butterfliesoflondona

About the London Natural History Society The London Natural History Society traces its history back to 1858. The Society is made up of a number of active sections that provide a wide range of talks, organised nature walks, coach trips and other activities. This range of events makes the LNHS one of the most active natural history societies in the world. Whether it is purely for recreation, or to develop field skills for a career in conservation, the LNHS offers a wide range of indoor and outdoor activities. Beginners are welcome at every event and gain access to the knowledge of some very skilled naturalists. LNHS LEARNING On top of its varied public engagement, the LNHS also provides a raft of publications free to members. The London Naturalist is its annual journal with scientific papers as well as lighter material such as book reviews. The annual London Bird Report published since 1937 sets a benchmark for publications of this genre. Furthermore, there is a quarterly Newsletter that carries many trip reports and useful announcements. The LNHS maintains its annual membership subscription at a modest level, representing fantastic value for money. Butterflies Distribution and Use of this PDF This PDF may be freely distributed in print or electronic form and can be freely uploaded to private or commercial websites provided it is kept in its entirety without any changes. The text and images should of London not be used separately without permission from the copyright holders. LNHS Learning materials, with the inner pages in a poster format for young audiences, are designed to be printed off and used on a class room wall or a child’s bedroom. -

Butterfly Descriptions

Butterfly Descriptions for Android App Hesperiidae Carcharodus alceae — Mallow Skipper Flight Time: April to October Elevation: 500-2600m Habitat: Meadows, forest clearings, and grassy hills. Food Plants: Malva sylvestris (Common Mallow), Althaea officinalis (Marshmallow) Life Cycle: Univoltine or multivoltine depending on elevation. Hesperia comma — Silver-Spotted Skipper Flight Time: Late June to early September Elevation: 2000-4000m Habitat: Mountainous meadows, steppes, and scree areas Food Plants: Festuca ovina (sheep’s fescue) Life Cycle: Eggs are laid singly on F. ovina. Species overwinters as an egg, hatching in March. Univoltine Muschampia proteus — No Common Name Flight time: June to August Elevation: Up to 2600m Habitat: Steppes, dry meadows, xerophytic gorges. Food Plants: N/A Life Cycle: N/A Pyrgus malvae — Grizzled Skipper Flight time: May to early July Elevation: 1000-3000m Habitat: Forest clearings, mountainous meadows, steppes Food Plants: Potentilla spp. (cinquefoil) and Rosa spp. (wild rose) Life Cycle: Eggs laid singly on host plant. Species overwinters as an egg. Likely univoltine. Spialia orbifer — Orbed Red-Underwing Skipper Flight time: Univoltine from May to August, bivoltine from April to June and July to August Elevation: Up to 3200m Habitat: Mountainous steppes, xerophytic meadows, and cultivated land. Food Plants: Rubus spp. (raspberry) and Potentilla spp. (cinquefoil) Life Cycle: N/A Thymelicus lineola — Essex Skipper Flight time: May to August. Elevation: Up to 2600m Habitat: Xerophytic slopes and grassy areas Food Plants: Dactylis spp. (cocksfoot grass) Life Cycle: Eggs are laid in a string near host plant. Species overwinters as an egg. Univoltine Lycaenidae Aricia agestis — Brown Argus Flight time: May to September Elevation: 1700-3800m Habitat: Dry meadows or steppe areas Food Plants: Erodium spp. -

Getting to Grips with Skippers Jonathan Wallace Dingy Skipper Erynnis Tages

Getting to Grips with Skippers Jonathan Wallace Skippers (Hesperidae) are a family of small moth-like butterflies with thick-set bodies and a characteristic busy, darting flight, often close to the ground. Eight species of skipper occur in the United Kingdom and three of these are found in the North East: the Large Skipper, the Small Skipper and the Dingy Skipper. Although with a little practice these charming butterflies are quite easily identified there are some potential identification pitfalls and the purpose of this note is to highlight the main distinguishing features. Dingy Skipper Erynnis tages This is the first of the Skippers to emerge each year usually appearing towards the end of April and flying until the end of June/early July (a small number of individuals emerge as a second generation in August in some years but this is exceptional). It occurs in grasslands where there is bare ground where its food plant, Bird’s-foot Trefoil occurs and is strongly associated with brownfield sites. The Dingy Skipper is quite different in appearance to the other two skippers present in our region, being (as the name perhaps implies) a predominantly grey-brown colour in contrast to the golden-orange colour of the other two. However, the species does sometimes get confused with two day-flying moth species that can occur within the same habitats: the Mother Shipton, Callistege mi, and the Burnet Companion, Euclidia glyphica. The photos below highlight the main differences. Wingspan approx. 28mm. Note widely spaced antennae with slightly hooked ends. Forewing greyish with darker brown markings forming loosely defined bands. -

Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia Dacotae) in Canada

Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series Recovery Strategy for the Dakota Skipper (Hesperia dacotae) in Canada Dakota Skipper 2007 About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.” What is recovery? In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured. What is a recovery strategy? A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage. Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies — Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada — under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/the_act/default_e.cfm) outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series. -

Butterflies of Scotland Poster

Butterflies shown at life-size, but Butterflies of Scotland there is some natural variation in size KEY Vanessids and Fritillaries Browns Whites Hairstreaks, Blues and Copper Skippers Comma Peacock Painted Lady Red Admiral Small Tortoiseshell Marsh Fritillary Pearl-bordered Fritillary Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary Dark Green Fritillary Ringlet Meadow Brown Speckled Wood Grayling Wall Scotch Argus Mountain Ringlet Small Heath Large Heath Large Heath polydama scotica Large White Small White Green-veined White Orange-tip (male) White-letter Hairstreak Green Hairstreak Purple Hairstreak Common Blue (male - female) Holly Blue (male - female) Small Blue Northern Brown Argus Small Copper Essex Skipper Small Skipper (male - female) Large Skipper Dingy Skipper Chequered Skipper At the time of publication in 2020, Scotland has 35 butterfly Wall: Lasiommata megera. Mostly found within a few miles Holly Blue: Celastrina argiolus. Known regularly only from a species which regularly breed here. The caterpillar of the coast in the SE and SW of Scotland, but populations small number of sites in the SW, Borders and East Lothian. foodplants (indicated by FP in each account), main flight are expanding inland in the Borders. Often observed basking Superficially similar to Common Blue, but undersides of period and distributions described apply only to Scotland. on bare ground to raise its body temperature. FP: a variety of wings are mostly plain blue-grey with black dots, and found in More details on distribution and descriptions of life cycles grasses, including Cock’s-foot, Yorkshire-fog, Bents and False different habitats such as garden gardens and graveyards. FP: can be found on the Butterfly Conservation website, and Brome. -

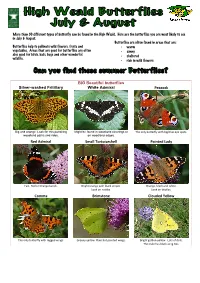

BIG Beautiful Butterflies Silver-Washed Fritillary White Admiral Peacock

More than 30 different types of butterfly can be found in the High Weald. Here are the butterflies you are most likely to see in July & August. Butterflies are often found in areas that are: Butterflies help to pollinate wild flowers, fruits and • warm vegetables. Areas that are good for butterflies are often • sunny also good for birds, bats, bugs and other wonderful • sheltered wildlife. • rich in wild flowers BIG Beautiful butterflies Silver-washed Fritillary White Admiral Peacock Big and orange. Look for this patrolling Might be found in woodland clearings or The only butterfly with big blue eye spots. woodland paths and rides. on woodland edges. Red Admiral Small Tortoiseshell Painted Lady Fast. Red or Orange bands. Bright orange with black stripes. Orange, black and white. Look on nettles. Look on thistles. Comma Brimstone Clouded Yellow The only butterfly with ragged wings. Greeny-yellow. Plain but pointed wings. Bright golden-yellow. Lots of dots. The male has black wing tips. Tiny Orange Butterflies Large Skipper Small Skipper Essex Skipper Blues Purple Hairstreak Light squares on wings. No light squares on wing. No light squares on Dark or grey antenae tips. wing. Black antenae tips. Look out for these at the tops of oak trees on sunny Small Copper Small Heath evenings after school. Holly Blue Bright orange. Likes rough grasses. Low flying. Likes very short grass. The Browns Light blue. Found near Meadow Brown Ringlet gardens or holly. Common Blue Brown with some orange. All brown with a white border. Likes yellow flowers. Found in fields & meadows. Likes brambles and hedgerows. -

Sentinels on the Wing: the Status and Conservation of Butterflies in Canada

Sentinels on the Wing The Status and Conservation of Butterflies in Canada Peter W. Hall Foreword In Canada, our ties to the land are strong and deep. Whether we have viewed the coasts of British Columbia or Cape Breton, experienced the beauty of the Arctic tundra, paddled on rivers through our sweeping boreal forests, heard the wind in the prairies, watched caribou swim the rivers of northern Labrador, or searched for song birds in the hardwood forests of south eastern Canada, we all call Canada our home and native land. Perhaps because Canada’s landscapes are extensive and cover a broad range of diverse natural systems, it is easy for us to assume the health of our important natural spaces and the species they contain. Our country seems so vast compared to the number of Canadians that it is difficult for us to imagine humans could have any lasting effect on nature. Yet emerging science demonstrates that our natural systems and the species they contain are increas- ingly at risk. While the story is by no means complete, key indicator species demonstrate that Canada’s natural legacy is under pressure from a number of sources, such as the conversion of lands for human uses, the release of toxic chemicals, the introduction of new, invasive species or the further spread of natural pests, and a rapidly changing climate. These changes are hitting home and, with the globalization and expansion of human activities, it is clear the pace of change is accelerating. While their flights of fancy may seem insignificant, butterflies are sentinels or early indicators of this change, and can act as important messengers to raise awareness. -

Butterflies on Ashdown Forest

Butterflies on Ashdown Forest SILVER-STUDDED BLUE Males blue with a dark border. Females brown with a row of red spots. Undersides brown-grey with black spots, a row of orange spots, and small greenish flecks on outer margin. Males are similar to Common Blue, which lacks greenish spots. This small butterfly is found mainly in heathland where the silvery- blue wings of the males provide a marvellous sight as they fly low over the heather. The females are brown and far less conspicuous but, like the male, have distinct metallic spots on the hindwing. In the late afternoon the adults often congregate to roost on sheltered bushes or grass tussocks. Butterfly Conservation priority: Medium UK BAP status: Priority Species GREEN HAIRSTREAK The Green Hairstreak holds its wings closed, except in flight, showing only the green underside with its faint white streak. The extent of this white marking is very variable; it is frequently reduced to a few white dots and may be almost absent. Males and females look similar and are most readily told apart by their behaviour: rival males may be seen in a spiralling flight close to shrubs, while the less conspicuous females are more often encountered while laying eggs. Although this is a widespread species, it often occurs in small colonies and has undergone local losses in several regions. Butterfly Conservation priority: Medium PURPLE EMPEROR This magnificent butterfly flies high in the tree-tops of well-wooded landscapes in central-southern England where it feeds on aphid honeydew and tree sap. The adults are extremely elusive and occur at low densities over large areas. -

Butterfly Conservation Cumbria Branch Newsletter 34 Spring 2017

Butterfly Conservation Cumbria Branch Newsletter 34 Spring 2017 Britain’s Skipper butterflies …… Large Skipper in Cumbria Small Skipper in Cumbria Essex Skipper not in Cumbria – yet? Lulworth Skipper – South coast Grizzled Skipper not in Cumbria Dingy Skipper in Cumbria Chequered Skipper – N W Scotland Silver Spotted Skipper – South England MESSAGE FROM our BRANCH CHAIRMAN Welcome to the Spring 2017 newsletter. As I write this we are close to the end of a busy Autumn-Winter season of conservation work parties. My highlights include the transformation of heavily scrubbed species rich limestone grassland at Wart Barrow near Allithwaite Quarry, Grange-O-Sands and the fritillary habitat restoration at Farrer’s Allotment at the southern end of Whitbarrow. (This site will be visited as a Summer field- trip...see later). Our next work-party programme will be published in August for 2017/18 but if you would like to find out more please contact me about work in South Cumbria and Steve Doyle [our editor] for work in North and West Cumbria. In this issue you will see details of over twenty guided walks or moth trapping events. You and family and friends are welcome to attend. Some will be joint events with the CWT and other natural history societies. The programme is also on our web-site but should you require more details please contact the walk leader. In addition you are all invited to our Open Day and AGM at the wonderful Marsh Fritillary site of Blackwood Farm near Keswick on Saturday 3rd June. This is our main event of the year so please put this in your diary now! [Details later in this newsletter.] Now entering its third year the number of people using our ‘sightings page’ has increased dramatically. -

Devon Branch Newsletter

Devon Branch www.devon-butterflies.org.uk Two Small Torties Gary Watson 26th August 2020 Newsletter Issue Number 109 October 2020 Butterfly Devon Branch Conservation Newsletter The Newsletter of Butterfly The Editor may correct errors Conservation Devon Branch in, adjust, or shorten articles if published three times a year. necessary, for the sake of accuracy, presen- tation and space available. Offerings may Copy dates: late December, late April, late occasionally be held over for a later newslet- August for publication in February, June, ter if space is short. and October in each year. The views expressed by contributors are not Send articles and images to the Editor necessarily those of the Editor or of Butterfly (contact details back of newsletter). Conservation either locally or nationally. Contents Roger Bristow 4 Annual General Meeting Long-tailed Blue 5 Small Tortoiseshell Pete Hurst Brown Argus Barry Henwood Silver Washed Fritillary Roger Brothwood 6 Comma Larva Bob Heckford 7 Sand Wasp John Rickett 8 Cbeebies Colin Sargent 10 Jersey Tiger-moth Carolyn Thomas 11 Haiku—Autumn Richard Stewart Essex Skipper Paul Butter 12 Disappearing Larvae part1 Pete Hurst 13 Lydford Transect report Colin Sargent 14 Quest for the White Letter Hairstreak Jacki and Kevin Solman 15 Brown Hairstreak egg survey Jenny Plackett 16 Latest report from Lydford Colin Sargent 17 Winter work party covid-19 safety guide 18 Winter Work Events 19 Art and Energy Naomi Wright 20 2020 Treasurers Report Ray Jones 22 Disappearing Larvae part 2 Pete Hurst 24 26 2 A note from your new editor Hello everyone, I’m Emma your new Butterfly Conservation Newsletter editor.