Appeal Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Item No. 9.2 Classification: Open Date: 6 March 2018 Meeting Name: Planning Committee Report Title: Development Management Plann

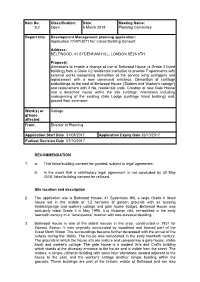

Item No. Classification: Date: Meeting Name: 9.2 Open 6 March 2018 Planning Committee Report title: Development Management planning application: Application 17/AP/3071 for: Listed Building Consent Address: BELTWOOD, 41 SYDENHAM HILL, LONDON SE26 6TH Proposal: Alterations to enable a change of use of Beltwood House (a Grade II listed building) from a Class C2 residential institution to provide 7 apartments with external works comprising demolition of the service wing outriggers and replacement with a new communal entrance. Demolition of curtilage outbuildings to the east of Beltwood House ('Stables and Worker's cottage') and replacement with 3 No. residential units. Creation of new Gate House and a detached house within the site curtilage. Alterations including underpinning of the existing Gate Lodge (curtilage listed building) and, ground floor extension. Ward(s) or College groups affected: From: Director of Planning Application Start Date 31/08/2017 Application Expiry Date 26/10/2017 Earliest Decision Date 07/10/2017 RECOMMENDATION 1. a. That listed building consent be granted, subject to legal agreement. b. In the event that a satisfactory legal agreement is not concluded by 30 May 2018, listed building consent be refused. Site location and description 2. The application site is Beltwood House, 41 Sydenham Hill, a large Grade II listed house set in the middle of 1.2 hectares of garden grounds with an outlying stables/garage and workers cottage and gate house (lodge). Beltwood House was statutorily listed Grade II in May 1995. It is Victorian villa, remodelled in the early twentieth century in a “renaissance” manner with neo-classical detailing. -

Five and Fifteen Year Housing Land Supply: 2018-2033 (December, 2019)

London Borough of Southwark Five and Fifteen Year Housing Land Supply: 2018-2033 (December, 2019) Contents 1. Executive summary .............................................................................................................. 2. Policy overview ................................................................................................................... 1 3. Southwark’s Housing Requirement .................................................................................... 7 4. Five and fifteen year land supply methodology.................................................................. 9 5. Summary of housing supply in Southwark ....................................................................... 13 Appendices Appendix 1- Five and fifteen year housing land supply Appendix 2 - Approved planning permissions in the pipeline List of tables Table 1: Policy overview Table 2: Housing Delivery Test results for Southwark Table 3: Completions on small sites (<0.25 hectares) Table 4: Five year land supply (A+B+C+D=E) Table 5: Six to fifteen year land supply (A+B=C) Abbreviations GLA – Greater London Authority HDT – Housing Delivery Test LBS – London Borough of Southwark LDD – London Development Database LPA – Local Planning Authority MHCLG - Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government NPPF – National Planning Policy Framework NPPG - National Planning Practice Guidance NSP – New Southwark Plan PPG – Planning Practice Guidance SHMA - Strategic Housing Market Assessment SHLAA - Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment -

London Borough of Southwark

London Borough of Southwark Five and Fifteen Year Housing Land Supply Update: 2020- 2036 (June, 2021 - updated) Contents 1. Executive summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Policy overview ............................................................................................................................... 3 3. Southwark’s Housing Requirement .............................................................................................. 13 4. Five and fifteen year land supply methodology ............................................................................... 15 5. Summary of housing supply in Southwark ........................................................................................ 22 Appendices Appendix 1- Five and fifteen year housing land supply Appendix 2 - Approved planning permissions in the pipeline Appendix 3 - New Council Homes Delivery pipeline List of tables Table 1: Policy overview Table 2: Housing Delivery Test results for Southwark Table 3: Prior Approvals from office to residential completions Table 4: Completions on small sites (<0.25 hectares) Table 5: Five year land supply Table 6: Six to fifteen year land supply Abbreviations GLA – Greater London Authority HDT – Housing Delivery Test LBS – London Borough of Southwark LDD – London Development Database LPA – Local Planning Authority MHCLG - Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government NPPF – National Planning Policy Framework NPPG - National -

INDEX to DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 a Key to Newsletter Numbers Can Be at Found After the Index Below

INDEX TO DULWICH SOCIETY NEWSLETTERS 1989-2014 A key to newsletter numbers can be at found after the index below. Abbeyfield 152.31 The Abbeyfield Society 119.29, 160.8 Abbott, George 1562-1633 166.27–28, 27 Able, Graham, Vice-President [1998-2000] 117.9, 138.8, 140.3 Abrahams, Adam 85.3–4 Acacia Grove 169.25–31, 26–27 extension 93.8–9, 94.47–48 Accounts Dulwich Estate 116.7, 120.30–32 Estates Governors 92.21–23, 97.30–32, 99.18 Accounts [1989] 85.33–34 Accounts [1990] 88.42–43, 92.11–13 Accounts [1991] 95.10–13 Accounts [1992] 98.6–7 Accounts [1994] 101.18–19 Accounts [2000] 125.11 Ackrill, Marion 123.30 Ackroyd, Norman 132.19, 19 Adam, Susan 93.31 Adie, Don, sub-ctee member [1994-] 101.20 Adult education centres 93.5 Advertising 88.8, 127.33–35, 129.29, 132.40 Advisory Committee for Scheme of Management 85.3, 20, 87.26, 88.5–6, 12, 90.8, 92.14–17, 94.35–38, 97.29–39, 98.8–9, 99.18–20, 102.32, 114.5–6, 120.8–11, 32, 130.13–14, 134.11–12, 145.13, 165.3 Agent Zigzag, Ben MacIntyre 159.30–31 AGM [1990] 88.9–11, 89.6 AGM [1991] 90.9, 91.2, 5 AGM [1992] 94.5, 95.6–13 AGM [1993] 97.4, 98.6–7 AGM [1994] 100.5, 101.16–19 AGM [1995]. 104.3, 105.5–6 AGM [1996] 108.5, 109.6–8 AGM [1997] 112.5 AGM [1998] 116.5, 117.7–10 AGM [1999] 120.5 AGM [2000] 124.9 AGM [2001] 128.5, 130.7–8 AGM [2002] 132.6 AGM [2003] 136.8 AGM [2004] 140.16 AGM [2005] 143.33, 144.3 AGM [2006] 147.33, 148.17 AGM [2007] 152.2, 9 AGM [2008] 156.21 AGM [2009] 160.6 AGM [2010] 164.12 AGM [2011] 168.5 AGM [2012] 172.6 AGM [2013] 176.5 Air Training Corps Squadron 153.6–7 Aircraft -

Heritage at Risk Register 2017, London

London Register 2017 HERITAGE AT RISK 2017 / LONDON Contents Heritage at Risk III The Register VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Reducing the risks XI Key statistics XIV Publications and guidance XV Key to the entries XVII Entries on the Register by local planning XIX authority Greater London 1 Barking and Dagenham 1 Barnet 2 Bexley 5 Brent 5 Bromley 6 Camden 11 City of London 18 Croydon 20 Ealing 23 Enfield 26 Greenwich 29 Hackney 33 Hammersmith and Fulham 39 Haringey 42 Harrow 46 Havering 49 Hillingdon 51 Hounslow 58 Islington 63 Kensington and Chelsea 70 Kingston upon Thames 80 Lambeth 81 Lewisham 90 London Legacy (MDC) 94 Merton 95 Newham 100 Redbridge 102 Richmond upon Thames 104 Southwark 107 Sutton 115 Tower Hamlets 116 Waltham Forest 123 Wandsworth 126 Westminster, City of 129 II London Summary 2017 he Heritage at Risk Register is a tool to help understand the ‘health’ of London’s historic environment. It includes buildings and sites known to be at risk from T neglect, decay or inappropriate development, helping to focus advice and support where it’s most needed. In London there are 683 sites on our Heritage at Risk Register – everything from the remains of a medieval moated manor house in Bromley, to a 1950s concrete sculpture on the Great West Road. Finding solutions to these sites isn’t easy, but we’re grateful for the support of all those who work tirelessly to protect our historic environment. Your efforts have helped to secure the future of 96% of buildings that appeared in our first published Register in 1991. -

S106 Non Financial Report 20

App No Address Description Decision Ward Type Deed Date Covenant Details Clause Service Owner Trigger Status Notes Commencement Date 05/AP/2617 89 SPA ROAD & SITE D Erection of building Granted Grange Ward (B&R) Wheelchair Units - Provision 13/09/2007 4.2 The Developer 4.2.2.3 Strategic Housing Prior to Occupation of more Not Started BERMONDSEY SPA extending to between 4 and covenants: than 50% of the Remaining BOUNDED BY SPA ROAD, 8 storeys in height to 4.2.2 that the Affordable Units ENID STREET, ROUEL ROAD provide 138 new dwellings Housing Units shall be & NECKINGER ESTATE, (38 social rented units, 31 completed and available for LONDON, SE16 3SG shared ownership units and residential Occupation no 69 private units) and 300m later than the Remaining of commercial space (use Units and (unless the classes A1, A2, and D1), Developer is a Registered together with the provision Social Landlord) handed of associated car parking, over to the Registered Social landscaping, infrastructure Landlord upon completion works and improvements to and that no more than 50% the existing playground of the Remaining Units shall area. be Occupied unless and until: 4.2.2.3 that 10 % (a total of 4 Affordable Housing Units) shall be provided as Wheelchair Compliant Units; 08/AP/0813 153-157 TOWER BRIDGE Erection of a 7 storey Granted Grange Ward (B&R) Wheelchair Units - Provision 08/06/2009 9.1. Prior to the Occupation S2,9 Strategic Housing Prior to Occupation Not Started ROAD, LONDON, SE1 3LW building at No. 157 and Date, the Developer shall change of use of part construct, appropriately fit existing building at No.153 out and thereafter retain comprising 1880sqm B1 the Wheelchair Accessible floorspace and 636sqm A1 Units for as long as the floorspace to provide: 137 Development or any part(s) room apart-hotel, 167sqm of it remain(s) Occupied for A1/B1 floorspace, 192sqm the purposes permitted by B1/D1 floorspace, 213sqm the Planning Permission. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2020, London and South East

London & South East Register 2020 HERITAGE AT RISK 2020 / LONDON AND SOUTH EAST Contents The Register IV Hastings 136 Lewes 138 Content and criteria IV Rother 138 Key statistics VI South Downs (NP) 139 Wealden 141 Key to the Entries VII Hampshire 142 Entries on the Register by local planning IX authority Basingstoke and Deane 142 East Hampshire 143 Greater London 1 Fareham 143 Barking and Dagenham 1 Gosport 144 Barnet 2 Hart 146 Bexley 3 Havant 147 Brent 4 New Forest 147 Bromley 6 New Forest (NP) 148 Camden 11 Rushmoor 149 City of London 17 Test Valley 152 Croydon 18 Winchester 154 Ealing 21 Isle of Wight (UA) 156 Enfield 23 Greenwich 27 Kent 161 Hackney 30 Ashford 161 Hammersmith and Fulham 37 Canterbury 162 Haringey 40 Dartford 164 Harrow 43 Dover 164 Havering 47 Folkestone and Hythe 167 Hillingdon 49 Maidstone 169 Hounslow 57 Sevenoaks 171 Islington 62 Swale 172 Kensington and Chelsea 67 Thanet 174 Kingston upon Thames 77 Tonbridge and Malling 176 Lambeth 79 Tunbridge Wells 177 Lewisham 87 Kent (off) 177 London Legacy (MDC) 91 Medway (UA) 178 Merton 92 Newham 96 Milton Keynes (UA) 181 Redbridge 99 Oxfordshire 182 Richmond upon Thames 100 Southwark 103 Cherwell 182 Sutton 110 Oxford 183 Tower Hamlets 112 South Oxfordshire 184 Waltham Forest 118 Vale of White Horse 186 Wandsworth 121 West Oxfordshire 188 Westminster, City of 123 Portsmouth, City of (UA) 189 Bracknell Forest (UA) 127 Reading (UA) 192 Brighton and Hove, City of (UA) 127 Southampton, City of (UA) 193 South Downs (NP) 130 Surrey 194 Buckinghamshire (UA) 131 Elmbridge 194 -

Heritage at Risk Register 2015, London

London Register 2015 HERITAGE AT RISK 2015 / LONDON Contents Heritage at Risk III The Register VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register IX Reducing the risks XI Key statistics XIV Publications and guidance XV Key to the entries XVII Entries on the Register by local planning XIX authority Greater London 1 Barking and Dagenham 1 Barnet 2 Bexley 5 Brent 5 Bromley 6 Camden 11 City of London 19 Croydon 20 Ealing 24 Enfield 27 Greenwich 30 Hackney 33 Hammersmith and Fulham 40 Haringey 42 Harrow 46 Havering 49 Hillingdon 52 Hounslow 58 Islington 64 Kensington and Chelsea 70 Kingston upon Thames 82 Lambeth 82 Lewisham 92 Merton 96 Newham 99 Redbridge 103 Richmond upon Thames 104 Southwark 107 Sutton 114 Tower Hamlets 115 Waltham Forest 122 Wandsworth 125 Westminster, City of 128 II London Summary 2015 or the first time, we’ve compared all sites on the Heritage at Risk Register – from houses to hillforts – to help us better understand which types of site are most Fcommonly at risk. There are things that make each region special and, once lost, will mean a sense of our region’s character is lost too. Comparing London to the national Register shows that 80.2% of all commemorative monuments and 57.6% of all public buildings are in our region. There are 670 entries on the London 2015 Heritage at Risk Register, making up 12.2% of the national total of 5,478 entries. The Register provides an annual snapshot of historic sites known to be at risk from neglect, decay or inappropriate development. -

Planning Committee Tuesday 6 March 2018 6.00 Pm Ground Floor Meeting Room G02 - 160 Tooley Street, London SE1 2QH

Open Agenda Planning Committee Tuesday 6 March 2018 6.00 pm Ground Floor Meeting Room G02 - 160 Tooley Street, London SE1 2QH Membership Reserves Councillor Nick Dolezal (Chair) Councillor James Barber Councillor Cleo Soanes (Vice-Chair) Councillor Catherine Dale Councillor Lucas Green Councillor Sarah King Councillor Lorraine Lauder MBE Councillor Jane Lyons Councillor Hamish McCallum Councillor Jamille Mohammed Councillor Darren Merrill Councillor Kieron Williams Councillor Michael Mitchell Councillor Adele Morris INFORMATION FOR MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC Access to information You have the right to request to inspect copies of minutes and reports on this agenda as well as the background documents used in the preparation of these reports. Babysitting/Carers allowances If you are a resident of the borough and have paid someone to look after your children, an elderly dependant or a dependant with disabilities so that you could attend this meeting, you may claim an allowance from the council. Please collect a claim form at the meeting. Access The council is committed to making its meetings accessible. Further details on building access, translation, provision of signers etc for this meeting are on the council’s web site: www.southwark.gov.uk or please contact the person below. Contact: Gerald Gohler on 020 7525 7420 or email: [email protected] Members of the committee are summoned to attend this meeting Eleanor Kelly Chief Executive Date: 26 February 2018 Planning Committee Tuesday 6 March 2018 6.00 pm Ground Floor Meeting Room G02 - 160 Tooley Street, London SE1 2QH Order of Business Item No. Title Page No. PART A - OPEN BUSINESS 1. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2014, London

2014 HERITAGE AT RISK 2014 / LONDON Contents Heritage at Risk III The Register VII Content and criteria VII Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Reducing the risks X Key statistics XIII Publications and guidance XIV Key to the entries XVI Entries on the Register by local planning XVIII authority Greater London 1 Barking and Dagenham 1 Barnet 2 Bexley 5 Brent 5 Bromley 6 Camden 11 City of London 20 Croydon 21 Ealing 24 Enfield 27 Greenwich 30 Hackney 33 Hammersmith and Fulham 40 Haringey 42 Harrow 46 Havering 50 Hillingdon 52 Hounslow 59 Islington 65 Kensington and Chelsea 70 Kingston upon Thames 82 Lambeth 82 Lewisham 92 Merton 96 Newham 99 Redbridge 104 Richmond upon Thames 105 Southwark 107 Sutton 115 Tower Hamlets 116 Waltham Forest 122 Wandsworth 125 Westminster, City of 128 II LONDON Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Over the past year we have focused much of our effort on assessing listed Places of Worship, and visiting those considered to be in poor or very bad condition as a result of local reports. We now know that of the 14,775 listed places of worship in England, 6% (887) are at risk and as such are included on this year’s Register. These additions mean the overall number of sites on the Register has increased to 5,753. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2019, London and South East

London & South East Register 2019 HERITAGE AT RISK 2019 / LONDON AND SOUTH EAST Contents The Register IV South Bucks 132 Wycombe 133 Content and criteria IV East Sussex 134 Key Statistics VI Eastbourne 134 Key to the Entries VII Hastings 135 Lewes 136 Entries on the Register by local planning IX authority Rother 137 South Downs (NP) 138 Greater London 1 Wealden 139 Barking and Dagenham 1 Hampshire 141 Barnet 2 Basingstoke and Deane 141 Bexley 3 East Hampshire 142 Brent 4 Fareham 142 Bromley 6 Gosport 142 Camden 10 Hart 144 City of London 17 Havant 145 Croydon 18 New Forest 145 Ealing 20 New Forest (NP) 146 Enfield 23 Rushmoor 147 Greenwich 26 Test Valley 150 Hackney 31 Winchester 152 Hammersmith and Fulham 36 Haringey 39 Isle of Wight (UA) 155 Harrow 42 Kent 160 Havering 46 Ashford 160 Hillingdon 48 Canterbury 161 Hounslow 55 Dartford 163 Islington 60 Dover 164 Kensington and Chelsea 65 Folkestone and Hythe 166 Kingston upon Thames 75 Gravesham 168 Lambeth 77 Maidstone 168 Lewisham 85 Sevenoaks 171 London Legacy (MDC) 89 Swale 172 Merton 90 Thanet 174 Newham 94 Tonbridge and Malling 176 Redbridge 97 Tunbridge Wells 176 Richmond upon Thames 99 Kent (off) 177 Southwark 102 Sutton 109 Medway (UA) 178 Tower Hamlets 110 Milton Keynes (UA) 181 Waltham Forest 116 Wandsworth 119 Oxfordshire 182 Westminster, City of 122 Cherwell 182 Bracknell Forest (UA) 126 Oxford 183 South Oxfordshire 184 Brighton and Hove, City of (UA) 127 Vale of White Horse 186 South Downs (NP) 129 West Oxfordshire 187 Buckinghamshire 130 Portsmouth, City of (UA) 189 Aylesbury -

Sydenham Hill Bus Lane Improvements the Lewisham (Bus Priority) (Sydenham Hill) (No

Public notice Sydenham Hill – bus lane improvements The Lewisham (Bus priority) (Sydenham Hill) (No. *) Traffic Order 201* The Lewisham (Waiting restrictions) (Sydenham Hill) (No. *) Order 201* The Southwark (Waiting and loading restrictions) (Amendment No. *) Order 201* 1. Southwark Council hereby GIVES NOTICE that it proposes to make the above orders under sections 6 and 124 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 19841, as amended, and with respect to the measures detailed in section 2(b) below regarding that part of Sydenham Hill which lies within London Borough of Lewisham, pursuant to agreement under section 19 of the Local Government Act 20002 with the council of said borough, in accordance with regulation 7 of the Local Authorities (Arrangements for the Discharge of Functions) (England) Regulations 20123. 2. The effect of the orders would be, in:- (a) SYDENHAM HILL (west and south-west side – in the London Borough of Southwark):- to extend an existing length of ‘at any time’ waiting restrictions at its junction with Westwood Hill, by approx. 90 metres north-westward, towards its junction with Chestnut Place; (b) SYDENHAM HILL (east and north-east side – in the London Borough of Lewisham) to:- (i) amend the length (to 110.5 metres) and the operating hours (to between 4 pm and 7 pm on Mon- Fri only) of the existing south-eastbound bus lane (for the use of buses, pedal cycles, solo motor cycles and taxis only) to be located between No. 4 Sydenham Hill and a point 34 metres south- east of the south-eastern kerb-line of Bluebell Close; (ii) amend sections of existing waiting restrictions located between its junction with Westwood Hill and a point 13 metres north-west of the north-western kerb-line of Bluebell Close, by adding approx.