Stirred, Not Yet Shaken: Integrating Women's History Into Media History*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

•Œdonald the Dove, Hillary the Hawkâ•Š:Gender in the 2016 Presidential Election

Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II Volume 23 Article 16 2019 “Donald the Dove, Hillary the Hawk”:Gender in the 2016 Presidential Election Brandon Sanchez Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sanchez, Brandon (2019) "“Donald the Dove, Hillary the Hawk”:Gender in the 2016 Presidential Election," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 23 , Article 16. Available at: https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/historical-perspectives/vol23/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sanchez: “Donald the Dove, Hillary the Hawk”:Gender in the 2016 Presidenti “Donald the Dove, Hillary the Hawk”: Gender in the 2016 Presidential Election Brandon Sanchez “Nobody has more respect for women than I do,” assured Donald Trump, then the Republican nominee for president, during his third and final debate with the Democratic nominee, former secretary of state Hillary Rodham Clinton, in late October 2016. “Nobody.” Over the scoffs and howls issued by the audience, moderator Chris Wallace tried to keep order—“Please, everybody!”1 In the weeks after the October 7th release of the “Access Hollywood” tape, on which Trump discussed grabbing women’s genitals against their will, a slew of harassment accusations had shaken the Trump campaign. -

2005 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS 6 Economic 10 Studies Global Economy and Development 27 Katrina’S Lessons in Recovery

QUALITY IMPACT AND INDEPENDENCE ANNUAL REPORT THE 2005 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 www.brookings.edu BROOKINGSINSTITUTION 2005 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS 6 Economic 10 Studies Global Economy and Development 27 Katrina’s Lessons in Recovery 39 Brookings Institution Press 14 40 Governance Center for Executive Education Studies 2 About Brookings 4 Chairman’s Message 5 President’s Message 31 Brookings Council 18 36 Honor Roll of Contributors Foreign 42 Financial Summary Policy Studies 44 Trustees 24 Metropolitan Policy Editor: Melissa Skolfield, Vice President for Communications Copyright ©2005 The Brookings Institution Writers: Katie Busch, Shawn Dhar, Anjetta McQueen, Ron Nessen 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 28 Design and Print Production: The Magazine Group, Inc. Washington, DC 20036 Jeffrey Kibler, Virginia Reardon, Brenda Waugh Telephone: 202-797-6000 Support for Production Coordinator: Adrianna Pita Fax: 202-797-6004 Printing: Jarboe Printing www.brookings.edu Cover Photographs: (front cover) William Bradstreet/Folio, Inc., Library of Congress Card Number: 84-641502 Brookings (inside covers) Catherine Karnow/Folio, Inc. Broadcast reporters zoom in for a forum on a new compact for Iraq THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION featuring U.S. Sen. Joseph Biden of Delaware. he Brookings Institution is a pri- vate nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and innovative policy solutions. Celebrating its 90th anniversary in 2006, Brookings analyzes current and emerging issues and produces new ideas that matter—for the nation and the world. ■ For policymakers and the media, Brookings scholars provide the highest-quality research, policy recommendations, and analysis on the full range of public policy issues. ■ Research at the Brookings Institution is conducted to inform the public debate, not advance a political agenda. -

The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2007 The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet Daniel J. Solove George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Solove, Daniel J., The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet (October 24, 2007). The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet, Yale University Press (2007); GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper 2017-4; GWU Legal Studies Research Paper 2017-4. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2899125 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2899125 The Future of Reputation Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2899125 This page intentionally left blank Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/ abstract=2899125 The Future of Reputation Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet Daniel J. Solove Yale University Press New Haven and London To Papa Nat A Caravan book. For more information, visit www.caravanbooks.org Copyright © 2007 by Daniel J. Solove. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. -

Matt-Lewis-And-The-Newsmakers.Pdf

1 Published by BBL & BWL, LLC / Produced by Athenry Media © 2018 BBL & BWL, LLC Alexandria, Virginia All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or modified in any form, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Part 1: Lessons on Success Jon Lovett .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Adam Carolla .................................................................................................................................... 8 Mitch McConnell ............................................................................................................................. 10 David Axelrod ................................................................................................................................... 11 Tucker Carlson ................................................................................................................................. 13 My Mom ............................................................................................................................................ 15 Part 2: Lessons on Relationships Sebastian Junger .............................................................................................................................. -

Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2018 Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate Hannah Hopper East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the American Politics Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Political Theory Commons, Social Influence and Political Communication Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Hopper, Hannah, "Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3402. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3402 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Media and Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Brand and Media Strategy _____________________ by Hannah Hopper May 2018 _____________________ Dr. Susan E. Waters, Chair Dr. Melanie Richards Dr. Phyllis Thompson Keywords: Political Journalist, Twitter, Agenda Setting, Framing, Gatekeeping, Feminist Political Theory, Political Polarization, Presidential Debate, Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump ABSTRACT Political Journalists Tweet About the Final 2016 Presidential Debate by Hannah Hopper Past research shows that journalists are gatekeepers to information the public seeks. -

Rice Determined Not to Strike in NJ | Huffpost

Rice Determined Not to Strike in NJ | HuffPost US EDITION THE BLOG 05/19/2014 03:52 pm ET | Updated Jul 19, 2014 Rice Determined Not to Strike in NJ By Marty Kaplan Forget whether former New York Times executive editor Jill Abramson was paid more or less than her predecessor, Bill Keller. I want to know why Condoleezza Rice was paid more than Condoleezza Rice. Rutgers University offered $35,000 to George W. Bush’s national security advisor and secretary of state to speak at its commencement exercises on Sunday. But just a few weeks ago, Rice got $150,000 for giving a speech at the University of Minnesota’s Hubert Humphrey School of Public Affairs. As it turned out, pushback from some Rutgers faculty and students caused Rice to bow out, saying she didn’t want to be a “distraction.” Still, she accepted their lowball offer in the first place. Why the deep discount? Was she planning to be 80 percent more platitudinous in New Jersey than in Minnesota? Or maybe it was a pro rata deal, and she going to speak for 14 minutes in New Brunswick instead of the hour she talked in Minneapolis. It couldn’t be that she was embarrassed to have had such a good payday at the Humphrey School. Her 150 bills is apparently what the graduation market will bear. As Inside Higher Ed has recounted, Katie Couric got $110K to give the University of Oklahoma commencement speech, and that was back in 2006. Three years ago, Rudy Giuliani’s fee was $100,000 plus the cost of a private jet to get him to the podium. -

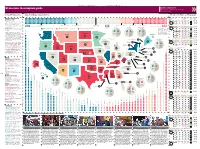

US Election: the Complete Guide Follow the Race

26 * The Guardian | Tuesday 6 November 2012 The Guardian | Tuesday 6 November 2012 * 27 Big news, small screen US election: the complete guide Live election results and commentary m.guardian.co.uk ≥ Follow the race The battleground states Work out who is winning Poll closes State How they voted Electoral college Election night 2012 on (GMT) 1988-2008 Votes Tally guardian.co.uk Bush Sr | Bush Sr | Dole | Live blog Wins, losses, too-close-to-calls, Indiana Bush | Bush | Obama 11 hanging chads — follow all the rollercoaster Bush Sr | Clinton | Clinton | action of election night as the results come Kentucky Bush | Bush | McCain 8 in with Richard Adams’s unrivalled live blog, 154 solid Democrat 29 likely to vote Democrat 18 leaning towards the Democrat 270 electoral college 11 leaning towards the Republicans 44 likely to vote Republican 127 solid Republican featuring dispatches from Guardian reporters votes needed to win Barack Obama and Democrats Mitt Romney and Republicans Bush Sr | Bush Sr | Clinton | and analysts across the US. 201 155 Wisconsin Michigan New Hampshire 182 Florida Bush | Bush | Obama Undecided 29 Live picture blog Our picture editors show Barack Obama & Democrats Mitt Romney & Republicans Undecided 1 Number of electoral college votes per state *Maine and Nebraska are the Bush Sr | Clinton | Dole | you the pick of the election images from both *Maine and Nebraska Georgia Bush | Bush | McCain 16 (+14) onlyare two the statestwo only that states allocate campaigns 55 theirthat electoral allocates college its votes Bush Sr | Clinton | Clinton | N Hampshire Bush | Kerry | Obama 4 Real time results Watch our amazing by electoralcongressional college district. -

Infographic by Ben Fry; Data by Technorati There Are Upwards of 27 Million Blogs in the World. to Discover How They Relate to On

There are upwards of 27 million blogs in the world. To discover how they relate to one another, we’ve taken the most-linked-to 50 and mapped their connections. Each arrow represents a hypertext link that was made sometime in the past 90 days. Think of those links as votes in an endless global popularity poll. Many blogs vote for each other: “blogrolling.” Some top-50 sites don’t have any links from the others shown here, usually because they are big in Japan, China, or Europe—regions still new to the phenomenon. key tech politics gossip other gb2312 23. Fark gouy2k 13. Dooce huangmj 22. Kottke 24. Gawker 40. Xiaxue 2. Engadget 4. Daily Kos 6. Gizmodo 12. SamZHU para Blogs 41. Joystiq 44. nosz50j 3. PostSecret 29. Wonkette 39. Eschaton 1. Boing Boing 7. InstaPundit 17. Lifehacker 25. chattie555 com/msn-sa 14. Beppe Grillo 18. locker2man 27. spaces.msn. 34. A List Apart 37. Power Line 16. Herramientas 43. AMERICAblog 20. Think Progress 35. manabekawori 49. The Superficial 9. Crooks and Liars11. Michelle Malkin 28. lwhanz198153030. shiraishi31. The seesaa Space Craft 50. Andrew Sullivan 19. Open Palm! silicn 33. spaces.msn.com/ 45. Joel46. on spaces.msn.com/Software 5. The Huffington Post 8. Thought Mechanics 15. theme.blogfa.com 21. Official Google Blog 38. Weebl’s Stuff News 47. princesscecicastle 32. Talking Points Memo 48. Google Blogoscoped 42. Little Green Footballs 26. spaces.msn. c o m/ 36. spaces.msn.com/atiger 10. spaces.msn.com/klcintw 1. Boing Boing A herald from the 6. -

Mistrial by Twitter”

A PRACTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR PREVENTING♦ “MISTRIAL BY TWITTER” INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 376 I. BACKGROUND ............................................................................... 376 A. Description of Twitter and Its Users ................................ 376 B. Twitter in the News .......................................................... 378 C. Twitter in the Jury Box ..................................................... 380 II. TWITTER AND JURORS .................................................................. 383 A. Twitter and Juror Misconduct .......................................... 384 1. Contact Between Third Parties and Jurors ................. 384 2. Exposure by Jurors to Extra-judicial, Non-evidentiary Materials ................................................................... 385 3. Conduct by Jurors that Evinces Bias and Prejudgment386 B. Analysis of Responses to Tweeting Jurors ...................... 387 1. Oregon (Multnomah County) – An Instruction to Jurors Selected to Serve ............................................ 388 2. Michigan – A Statewide Court Rule Amendment ...... 389 3. Connecticut – A Statewide Study of the Juror’s “Life Cycle” ....................................................................... 390 4. Federal Courts – A Memo from the Top .................... 391 III. PROPOSALS ................................................................................. 393 A. The Judiciary Must Be Trained to Evaluate Possible Harmful -

U.S. Attorneys Scandal and the Allocation of Prosecutorial Power

"The U.S. Attorneys Scandal" and the Allocation of Prosecutorial Power BRUCE A. GREEN* & FRED C. ZACHARIAS** I. INTRODUCTION In 1940, Attorney General (and future Supreme Court Justice) Robert H. Jackson spoke to United States Attorneys about their duty not only to be "diligent, strict, and vigorous in law enforcement" but also "to be just" and to "protect the spirit as well as the letter of our civil liberties."' His talk was dedicated mostly to the relationship between the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the U.S. Attorneys in their shared pursuit of justice. On one hand, he observed that "some measure of centralized control is necessary" to ensure consistent interpretations and applications of the law, to prevent the pursuit of "different conceptions of policy," to promote performance standards, and to provide specialized assistance.2 On the other hand, he acknowledged that a U.S. Attorney should rarely "be superseded in handling of litigation" and that it would be "an unusual case in which his judgment 3 should be overruled." Critics of George W. Bush's administration have charged that the balance in federal law enforcement has tipped in the direction of too little prosecutorial independence and too much centralized control. 4 One of their prime examples is the discharge of eight U.S. Attorneys in late 2006,5 which * Louis Stein Professor of Law and Director, Louis Stein Center for Law and Ethics, Fordham University School of Law. The authors thank Michel Devitt, Graham Strong, and Sharon Soroko for commenting on earlier drafts and Brian Gibson, David Sweet, and Kimber Williams for their invaluable research assistance. -

Religious Liberty and the American Culture Wars Dr. John Inazu Washington University of Law, St. Louis May 2015

TRANSCRIPT Religious Liberty and the American Culture Wars Dr. John Inazu Washington University of Law, St. Louis May 2015 MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Well, ladies and gentlemen, in keeping with our tradition of making sure that our topics are topical and up to date, here we are on “Religious Liberty and the American Culture Wars.” Professor John Inazu, as you know from the bio, is Associate Professor of Law and Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis. His law degree is from Duke University, his undergrad degree is from Duke University, and his Ph.D. in Political Science is from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. And I asked him when Carolina and Duke play in basketball, who does he pull for? He’s a former Cameron Crazy. Actually painted his body I think when he was an undergrad there and stood on the sidelines with the other Duke fans. JOHN INAZU: Off the record. Laughter MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Yes, off the record. It might be too late. Laughter MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Professor Inazu’s first book is called Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly, published by Yale University Press. He has a new book coming out called Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Difference. Confident Pluralism. So when will that be out, John? TRANSCRIPT “Religious Liberty and the American Culture Wars” Dr. John Inazu May 2015 JOHN INAZU: It’s not formally approved, but it would be the Spring ’16 list if it happens, so it would be early ’16 or late ’15. MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Confident Pluralism, ladies and gentlemen. -

Quantising Opinions for Political Tweets Analysis

Quantising Opinions for Political Tweets Analysis Yulan He1, Hassan Saif1, Zhongyu Wei2, Kam-Fai Wong2 1Knowledge Media Institute, The Open University, UK fy.he, [email protected] 2Dept. of Systems Engineering & Engineering Management The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong fzywei, [email protected] Abstract There have been increasing interests in recent years in analyzing tweet messages relevant to political events so as to understand public opinions towards certain political issues. We analyzed tweet messages crawled during the eight weeks leading to the UK General Election in May 2010 and found that activities at Twitter is not necessarily a good predictor of popularity of political parties. We then proceed to propose a statistical model for sentiment detection with side information such as emoticons and hash tags implying tweet polarities being incorporated. Our results show that sentiment analysis based on a simple keyword matching against a sentiment lexicon or a supervised classifier trained with distant supervision does not correlate well with the actual election results. However, using our proposed statistical model for sentiment analysis, we were able to map the public opinion in Twitter with the actual offline sentiment in real world. Keywords: Political tweets analysis, sentiment analysis, joint sentiment-topic (JST) model 1. Introduction timent classifiers based on emoticons contained in tweet messages (Go et al., 2009; Pak and Paroubek, 2010) or The emergence of social media has dramatically changed manually annotated tweets data (Vovsha and Passonneau, people’s life with more and more people sharing their 2011). However, these approaches can’t be generalized thoughts, expressing opinions, and seeking for support on well since not all tweets contain emoticons and it is also social media websites such as Twitter, Facebook, wikis, fo- difficult to obtain annotated tweets data in real-world appli- rums, blogs etc.