Wading Through Space and Time: Leveraging Geospatial Methods to Better Understand Recreation Behavior, Experience, and Impacts Within a Densely Used Lake Destination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Teton National Park Youngest Range in the Rockies

GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK YOUNGEST RANGE IN THE ROCKIES the town of Moran. Others recognized that dudes winter better than cows and began operating dude ranches. The JY and the Bar BC were established in 1908 and 1912, respectively. By the 1920s, dude ranch- ing made significant contributions to the valley’s economy. At this time some local residents real- ized that scenery and wildlife (especially elk) were valuable resources to be conserved rather than exploited. Evolution of a Dream The birth of present-day Grand Teton National Park involved controversy and a struggle that lasted several decades. Animosity toward expanding governmental control and a perceived loss of individual freedoms fueled anti-park senti- ments in Jackson Hole that nearly derailed estab- lishment of the park. By contrast, Yellowstone National Park benefited from an expedient and near universal agreement for its creation in 1872. The world's first national park took only two years from idea to reality; however Grand Teton National Park evolved through a burdensome process requiring three separate governmental Mt. Moran. National Park Service Photo. acts and a series of compromises: The original Grand Teton National Park, set Towering more than a mile above the valley of dazzled fur traders. Although evidence is incon- aside by an act of Congress in 1929, included Jackson Hole, the Grand Teton rises to 13,770 clusive, John Colter probably explored the area in only the Teton Range and six glacial lakes at the feet. Twelve Teton peaks reach above 12,000 feet 1808. By the 1820s, mountain men followed base of the mountains. -

Stranded – Cited for Creating Hazard Wyoming, Mt

AAC Publications Stranded – Cited for Creating Hazard Wyoming, Mt. Moran, Falling Ice Glacier On August 11, at approximately 4 p.m., a woman went to the Lupine Meadows Rescue Cache to report that her friend, a 30-year-old male, was stuck on Mt. Moran and needed help. They had had been communicating by two-way family radio. With the use of the radio, it was confirmed that he was on the Falling Ice Glacier on Mt. Moran and unable to descend. Based on the stranded climber’s location, lateness of the day, availability of the park contract helicopter, and the fact that a ground-based rescue would put rangers into an area known to have considerable rockfall and icefall hazard, it was determined that a helicopter evacuation would be the safest form of rescue. At 5:45 p.m., helicopter 38HX left Lupine Meadows with rangers Bellino and Jernigan aboard. The helicopter landed directly on the glacier, near the stranded climber’s location, and the rangers helped the climber onboard the aircraft along with his pack for the flight back to Lupine Meadows. ANALYSIS Rangers interviewed the rescued individual in an effort to find out why he was in a position to need a rescue. He stated that he had acquired his information about climbing Mt. Moran from Summit Post, an online mountaineering resource. He did not consult any of the local publications nor stop at the Jenny Lake Ranger Station to acquire current route information. He was equipped with mountaineering boots, ice axe, crampons, harness, belay device, five meters of small-diameter rope, several carabiners, and camping equipment. -

Exploring Grand Teton National Park

05 542850 Ch05.qxd 1/26/04 9:25 AM Page 107 5 Exploring Grand Teton National Park Although Grand Teton National Park is much smaller than Yel- lowstone, there is much more to it than just its peaks, a dozen of which climb to elevations greater than 12,000 feet. The park’s size— 54 miles long, from north to south—allows visitors to get a good look at the highlights in a day or two. But you’d be missing a great deal: the beautiful views from its trails, an exciting float on the Snake River, the watersports paradise that is Jackson Lake. Whether your trip is half a day or 2 weeks, the park’s proximity to the town of Jackson allows for an interesting trip that combines the outdoors with the urbane. You can descend Grand Teton and be living it up at the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar or dining in a fine restaurant that evening. The next day, you can return to the peace of the park without much effort at all. 1 Essentials ACCESS/ENTRY POINTS Grand Teton National Park runs along a north-south axis, bordered on the west by the omnipresent Teton Range. Teton Park Road, the primary thoroughfare, skirts along the lakes at the mountains’ base. From the north, you can enter the park from Yellowstone National Park, which is linked to Grand Teton by the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway (U.S. Hwy. 89/191/287), an 8-mile stretch of highway, along which you might see wildlife through the trees, some still bare and black- ened from the 1988 fires. -

2021 Jackson Area Angler Newsletter

Wyoming Game and Fish Department Jackson Region Angler Newsletter Inside this issue: Volume 15 2021 Leigh Lake 2 Fish Management in the Jackson Region Sampling Welcome to the 2021 Jackson Region Angler Newsletter! Even though it was a year like no other, we had another great year managing the Jackson area fisheries. Inside Sam Gertsch 3 receives Ultimate you’ll find updates from our work in 2020 and some of the upcoming work for 2021. Angler Status As always, please feel free to contact us or stop by with any comments or questions Beaver Dam 4 about the aquatic resources in western Wyoming. Your input is important to us as Analogs we manage these resources for you. You’ll find all of our contact info on the last Lower Slide Lake 6 page of this newsletter. Stocking Changes Bullfrogs at Kelly 7 Warm Springs Understanding 8 Gill Lice in the Snake River Drainage Aquatic Invasive 9 Species Rob’s Hanging Up 10 Rob Gipson Fisheries Supervisor His Waders Important Dates 12 in 2021 Diana Miller Clark Johnson Fisheries Biologist Fisheries Biologist Anna Senecal Chris Wight Aquatic Habitat Biologist AIS Specialist Page 2 Jackson Region Angler Newsletter Leigh Lake Sampling Leigh Lake is a relatively large, glacial lake in Grand Teton National Park. It is roughly 2.5 miles wide and nearly 3 miles long, with a max depth of 250 feet. It sits to the north of Jenny Lake and south of Jackson Lake’s Moran Bay. Leigh Lake can be accessed one of two ways, either via the Leigh Lake Trail or paddling up String Lake. -

Naturalist Pocket Reference

Table of Contents Naturalist Phone Numbers 1 Park info 5 Pocket GRTE Statistics 6 Reference Timeline 8 Name Origins 10 Mountains 12 Things to Do 19 Hiking Trails 20 Historic Areas 23 Wildlife Viewing 24 Visitor Centers 27 Driving Times 28 Natural History 31 Wildlife Statistics 32 Geology 36 Grand Teton Trees & Flowers 41 National Park Bears 45 revised 12/12 AM Weather, Wind Scale, Metric 46 Phone Numbers Other Emergency Avalanche Forecast 733-2664 Bridger-Teton Nat. Forest 739-5500 Dispatch 739-3301 Caribou-Targhee NF (208) 524-7500 Out of Park 911 Grand Targhee Resort 353-2300 Jackson Chamber of Comm. 733-3316 Recorded Information Jackson Fish Hatchery 733-2510 JH Airport 733-7682 Weather 739-3611 JH Mountain Resort 733-2292 Park Road Conditions 739-3682 Information Line 733-2291 Wyoming Roads 1-888-996-7623 National Elk Refuge 733-9212 511 Post Office – Jackson 733-3650 Park Road Construction 739-3614 Post Office – Moose 733-3336 Backcountry 739-3602 Post Office – Moran 543-2527 Campgrounds 739-3603 Snow King Resort 733-5200 Climbing 739-3604 St. John’s Hospital 733-3636 Elk Reduction 739-3681 Teton Co. Sheriff 733-2331 Information Packets 739-3600 Teton Science Schools 733-4765 Wyoming Game and Fish 733-2321 YELL Visitor Info. (307) 344-7381 Wyoming Highway Patrol 733-3869 YELL Roads (307) 344-2117 WYDOT Road Report 1-888-442-9090 YELL Fill Times (307) 344-2114 YELL Visitor Services 344-2107 YELL South Gate 543-2559 1 3 2 Concessions AMK Ranch 543-2463 Campgrounds - Colter Bay, Gros Ventre, Jenny Lake 543-2811 Campgrounds - Lizard Creek, Signal Mtn. -

Backpacking-The-Teton-Crest-Trail

The Big Outside Complete Guide to Backpacking the Teton Crest Trail in Grand Teton National Park © 2019 Michael Lanza All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying or other electronic, digital, or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, contact the publisher at the address below. Michael Lanza/The Big Outside 921 W. Resseguie St. Boise, ID 83702 TheBigOutside.com Hiking and backpacking is a personal choice and requires that YOU understand that you are personally responsible for any actions you may take based on the information in this e-guide. Using any information in this e-guide is your own personal responsibility. Hiking and associated trail activities can be dangerous and can result in injury and/or death. Hiking exposes you to risks, especially in the wilderness, including but not limited to: • Weather conditions such as flash floods, wind, rain, snow and lightning; • Hazardous plants or wild animals; • Your own physical condition, or your own acts or omissions; • Conditions of roads, trails, or terrain; • Accidents and injuries occurring while traveling to or from the hiking areas; • The remoteness of the hiking areas, which may delay rescue and medical treatment; • The distance of the hiking areas from emergency medical facilities and law enforcement personnel. LIMITATION OF LIABILITY: TO THE FULLEST EXTENT PERMISSIBLE PURSUANT TO APPLICABLE LAW, NEITHER MICHAEL LANZA NOR THE BIG OUTSIDE, THEIR AFFILIATES, FAMILY AND FORMER AND CURRENT EMPLOYERS, NOR ANY OTHER PARTY INVOLVED IN CREATING, PRODUCING OR DELIVERING THIS E-GUIDE IS LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INCIDENTAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, INDIRECT, EXEMPLARY, OR PUNITIVE DAMAGES ARISING OUT OF A USER’S ACCESS TO, OR USE OF THIS E-GUIDE. -

A Brief History of the Trails of Grand Teton National Park 55

Pritchard: A Brief History of the Trails of Grand Teton National Park 55 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE TRAILS OF GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK JAMES A. PRITCHARD IOWA STATE UNIVERSITY AMES ABSTRACT reconstructed during the MISSION 66 era, but some of the stone stairs along the way from the boat dock This project investigated the history of the to Hidden Falls date back to the CCC era. backcountry trail system in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP). In cooperation with GTNP Cultural Walking on a beautiful mountain path, one Resources and the Western Center for Historic might never guess the extensive preparation of rock Preservation in GTNP, we located records describing materials (expediting drainage) that is required before the early development of the trail system. Only a few the surface ―treadway‖ is laid down (Barter et al. historical records describe or map the exact location 2006). In fact, trails are significant engineering of early trails, which prove useful when relocating achievements that need constant care and upkeep, trails today. The paper trail becomes quite rich, including annual clearance of vegetation and the however, in revealing the story behind the practical occasional repair to sections of trail. development of Grand Teton National Park as it joined the National Park Service system. Pre-existing Trails Archeological sites are present in the upper INTRODUCTION parts of Berry Creek drainage, thought to represent ―basecamps‖ occupied consistently over 8,000 years. Grand Teton National Park and its trail A notable pre-historic travel route traversed the system developed together during the early years of northern end of the Teton Range, from the west into National Park Service (NPS) administration. -

Holly Lake, Located in Paintbrush Canyon, Is Fastest Accessed from the String Lake Trailhead of Grand Tetons National Park. It

! HOLLY LAKE, GRAND TETONS NATIONAL PARK Holly Lake, located in Paintbrush Canyon, is fastest accessed from the String Lake trailhead of Grand Tetons National Park. It is 1.6 miles to the junction with the trail from Leigh Lake (which is also 1.6 miles but supposedly has a steeper incline than the trail from String Lake). It is then an additional 4.9 miles to Holly Lake, making the round-trip distance 13 miles total. The trailhead is located at an elevation of 6,880 ft, and the lake is located at 9,450 ft. The trail is quite easy to find and is well-travelled, though we did not encounter many hikers on the trail. Note that it is not safe to begin this hike !late in the day! On our drive in to Wilson, WY the previous day, we drove the Teton Scenic Byway and stopped to take a photo of this sign: ! ! Parking for the Holly Lake hike at the String Lake trailhead; if you arrive at the trailhead "early", ~8:00 am, there are very few vehicles (mainly those from hikers staying overnight), and can have a good selection of parking spaces; however, arriving later in the day (for a shorter hike, for example), parking would be difficult: ! ! Panorama of the tetons from near the trailhead: ! ! Panorama of Leigh Lake: ! ! Leigh Lake: ! ! Another panorama from the trail along the western rim of Leigh Lake: ! ! The trail leaves the rim of Leigh Lake near the northern end of the lake and ascends through some short trees: ! ! This may be a potential route to Rockchuck Peak, as we saw a hiker leave the trail near here who appeared to ascend towards the distant -

Backcountry Camping Brochure

National Park Service Grand Teton U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Teton National Park John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway Backcountry Camping The North Fork of Cascade Canyon - Danielle Lehle photo Before Leaving Home Weather Planning Your Trip Group Size Boating This guide provides general information about backcountry use in Grand Teton National Individual campsites accommodate one to Register all vessels annually with the park. Park and the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway. The map on the back page is six people. Groups of seven to 12 people Purchase permits at the Craig Thomas, only for general trip planning and/or campsite selection. For detailed information, use a must use designated group sites that are Colter Bay or Jenny Lake (cash only) visitor topographic map or hiking guide. When planning your trip, consider each member of your larger and more durable. In winter, parties centers. Lakeshore campsites are located party. Backpackers should expect to travel no more than 2 miles per hour, with an additional are limited to 20 people. on Jackson and Leigh lakes. Camping is hour for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain. Do not plan to cross more than one mountain not allowed along the Snake River. Strong The table below summarizes weather at Moose, WY, 6467 feet. Temperatures in the Teton pass in a day. If you only have one vehicle, you may want to plan a loop trip. There is no Backcountry Conditions afternoon winds occur frequently. For Range can change quickly and be much colder at upper elevations. Check the local area shuttle service in the park, but transportation services are available; ask at a permits desk for Snow conditions vary annually. -

Grand Teton Lodge Company

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Teton Grand Teton National Park John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway Day Hikes National Park G r d 1 a a s s o y R Flagg Ranch Lake Grand Teton John D. Be Bear Aware! Rockefeller, Jr. It all smells to a bear Memorial Please take care Parkway Lock it up! Food Storage Required North 0 1 Kilometer 5 0 1 Mile 5 ON NY CA B EB W 89 E 191 K 287 A L GRAND TWO OCEAN LAKE N 2 Colter Bay O 4 TETON S K C . A t P 3 J NATIONAL e g Jackson EMMA a it Lake Lodge MATILDA LAKE rm e PARK H Signal 26 287 E Signal Mountain Mountain G Lodge 5 N LEIGH For Your Safety Paintbrush A LAKE • BE BEAR AWARE! Avoid surprising bears by Divide R Holly N Lake O 6 making noise—call out and clap your hands. Y N String Lake P A 7 AI C Lake NT SH The use of personal audio devices is strongly Solitude BRU R E 17 V I discouraged. R JENNY NAKE • Carry bear spray and know how to use it. Be 16 S C A SCADE CANYON LAKE 8 sure not to spray it accidentally. Teton South Amphitheater Jenny Lake Canyon N Lake • Proper food storage is required. Ask a ranger O 9 for more information. G T A ALASKA RN ET • Carry drinking water. BASIN E CANYON T Bradley • Be prepared for rapid weather changes; (USFS) Lake Taggart bring rain gear and extra clothing. -

Paintbrush Divide Loop Trail

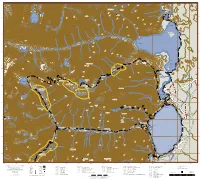

-110.860 -110.850 -110.840 -110.830 -110.820 -110.810 -110.800 -110.790 -110.780 -110.770 -110.760 -110.750 -110.740 -110.730 -110.720 -110.710 9 , 6 0 0 0 0 8 , 0 00 6 1 6 ,60 8, 1 0 1 , 2 0 0 Mount Moran 12605 T East Horn ra p 9, 00 Trapper p 2 e r Lake L a 0 k 60 e , 1 T 1 .55 r 00 West Horn ,0 1 1 0 0 Thor Peak 6 , 43.830 0 1 43.830 Cirque Lake 0 0 00 4 ,4 Bearpaw Lake , 9 .25 9 00 ,6 0 0 1 0 6 , 0 9 0 1 0 ,8 0,0 0 8 .35 7,200 0 0 8 8,200 , 8,4 7 00 00 9,2 Leigh Lake 0 0 0 , 9 8,0 00 L e ig h L a k e Mystic Island 0 T 43.820 00 r 43.820 8, a i l 7,400 1.30 0 Leigh Canyon 7,00 9,200 7, 200 0 8,00 Leigh Lake 9,4 00 8,600 Mink Lake 0 0 6 0, 43.810 43.810 1 9,600 8 ,800 00 ,8 9 0 9,00 0 0 ,4 8 0 ,40 10 7 9,6 ,400 00 Grizzly Bear Lake Hol 4.90 ly La k e 0 Mount Woodring 11590 T 0 7,600 ra Leigh Lake ,4 il 0 1 0 l 0 i 0 0 00 a 1 0 1,4 2 r , , 1 7 T 1 0 e 0 k 8,0 a Boulder Island L h 43.800 g 43.800 9,8 i 00 e L ail Tr S n ke tri g Lak La e T lly r .75 1.50 Ho 10,400 8 , 80 0 00 9,8 Outlier Site 0 9, 60 0 0 2 P , ai 1 7 .80 ntb 0,6 1.75 rus 00 h Di 10,60 8 vid 0 ,4 00 e T ra 1.30 il Holly Lake Site Holly Lake 00 9 Paintbrush Divide 0 ,4 Lake Solitude ,4 10,00 9 00 9 ,2 0 2.25 0 Paint 0 0 N bru ,0 il s 8 ra o h C T r 10 ke t ,8 a a h L 0 n 0 g F y n on Tr ri o Paintbrush Canyon a t Cathedral Group r 9 il S 43.790 k ,8 43.790 00 il Turnout o Holly Lake Group Site ra f T e C k a La s lly 1 c 9,200 Ho 0 ad ,0 e Ca p 0 ny oo 0 on Rockchuck Peak L ke North Fork of S a L tr y i n 00 n n Cascade Canyon 9,6 g e J L .55 a k e T d r Access a Ramp o -

Grand Teton Guide

GGGRRRAAANNNDDD TTTEEETTTOOONNN GGGUUUIIIDDDEEE nnnooo... 777 AN AMATEUR’S REVIEW OF BACKPACKING TOPICS FOR THE 2008 T254 EXPEDITION TO GRAND TETONS / YELLOWSTONE GGGRRRAAANNNDDD TTTEEETTTOOONNN GGGEEEOOOLLLOOOGGGYYY The Teton Range is the center point of the park, rising more than 7,000 feet above the floor of Jackson's Hole which borders the mountain range to the east. The steep eastern front of the range is unique in the Rocky Mountains and similar to the steep eastern front of the Sierra Nevada. It is the result of rapid uplift along the Teton fault and subsequent episodes of glacial erosion. The summit of Grand Teton at 13,770 feet is the second highest mountain in Wyoming. The image above is a highly generalized geologic map (after Smith and Siegel,2000). The oldest rocks in the Teton Range are 2.8 Ga gneisses and schists and 2.4 Ga granite. These were subsequently intruded by dark-colored diabase dikes around 1.1-1.3 Ga. The best known locality where this relationship can be seen is the oft- photographed Mt.Moran, shown to the right. The crosscutting diabase dike is the dark, almost black rock. The sliver of light brown colored rock at the summit of Mt. Moran is 560 Ma Flathead Sandstone. The Precambrian basement rocks are overlain unconformably by Paleozoic sedimentary rocks. These rocks are exposed on the gentle west slope of the Teton Range forming "The Wall", a massive sequence of stratified rocks that can be seen looking westward from the floor of Jackson's Hole . Most of the sedimentary rocks were deposited in shallow marine seas during a sequence of transgressions and regressions from the Cambrian through Mississippian.Younger Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks were probably deposited in the Teton region but subsequently removed by erosion from the western slope of the Tetons, a consequence of uplift along the Teton Fault.