Effects of the Suwannee River Sill on the Hydrology of the Okefenokee Swamp: Application of Research Results in the Environmental Assessment Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River Named Among America's

Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River named Among America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2020 Mining threatens, fish and wildlife habitat; wetlands; water quality and flow Contact: Ben Emanuel, American Rivers, 706-340-8868 Christian Hunt, Defenders of Wildlife 828-417-0862 Rena Ann Peck, Georgia River Network, 404-395-6250 Alice Miller Keyes, One Hundred Miles, 912-230-6494 Alex Kearns, St. Marys EarthKeepers, 912-322-7367 Washington, D.C. –American Rivers today named the Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River among America’s Most Endangered Rivers®, citing the threat titanium mining would pose to the waterways’ clean water, wetlands and wildlife habitat. American Rivers and its partners called on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other permitting agencies to deny any proposals that risk the long-term protection of the Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River. “America’s Most Endangered Rivers is a call to action,” said Ben Emanuel, Atlanta- based Clean Water Supply Director with American Rivers. “Some places are simply too precious to allow risky mining operations, and the edge of the unique Okefenokee Swamp is one. The Army Corps of Engineers must deny the permit to save this national treasure.” The annual America’s Most Endangered Rivers report is a list of rivers at a crossroads, where key decisions in the coming months will determine the rivers’ fates. Over the years, the report has helped spur many successes including the removal of outdated dams, the protection of rivers with Wild and Scenic designations, and the prevention of harmful development and pollution. Rena Ann Peck, Executive Director of Georgia River Network, explains "The Okefenokee Swamp is like the heart of the regional Floridan aquifer system in southeast Georgia and northeast Florida. -

Plant Succession on Burned Areas in Okefenokee Swamp Following the Fires of 1954 and 1955 EUGENE CYPERT Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge U.S

Plant Succession on Burned Areas in Okefenokee Swamp Following the Fires of 1954 and 1955 EUGENE CYPERT Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and 'Wildlife Waycross, GA 31501 INTRODUCTION IN 1954 and 1955, during an extreme drought, five major fires occurred in Okefenokee Swamp. These fires swept over approximately 318,000 acres of the swamp and 140,000 acres of the adjacent upland. In some areas in the swamp, the burning was severe enough to kill most of the timber and the understory vegetation and burn out pockets in the peat bed. Burns of this severity were usually small and spotty. Over most of the swamp, the burns were surface fires which generally killed most of the underbrush but rarely burned deep enough into the peat bed to kill the larger trees. In many places the swamp fires swept over lightly, burning surface duff and killing only the smaller underbrush. Some areas were missed entirely. On the upland adjacent to the swamp, the fires were very de structive, killing most of the pine timber on the 140,000 acres burned over. The destruction of pine forests on the upland and the severe 199 EUGENE CYPERT burns in the swamp caused considerable concern among conservation ists and neighboring land owners. It was believed desirable to learn something of the succession of vegetation on some of the more severely burned areas. Such knowl edge would add to an understanding of the ecology and history of the swamp and to an understanding of the relation that fires may have to swamp wildlife. -

* This Is an Excerpt from Protected Animals of Georgia Published By

Common Name: BLACKBANDED SUNFISH Scientific Name: Enneacanthus chaetodon Other Commonly Used Names: none Previously Used Scientific Names: none Family: Centrarchidae Rarity Ranks: G4/S1 State Legal Status: Endangered Federal Legal Status: Not Listed Description: The blackbanded sunfish is a small, laterally compressed and deep-bodied species reaching a maximum total length of 100 mm (4 inches). There is a prominent notch separating the spinous and soft-rayed portions of the dorsal fin. It is distinctively marked with 5-6 black bars along the sides that extend from the dorsum to the venter. The first of these bars passes through the eye, and the third extends through the first three membranes of the spinous dorsal fin to the upper edge of the fin. No other sunfish has this barring pattern. The blackbanded sunfish is also very colorful with black vertical bars, olive-brown to variegated-brown on the dorsum and upper sides, and orange-copper marking the leading edge of the pelvic fins and the irises. Similar Species: The small body size and distinctive color pattern make it difficult to confuse the blackbanded sunfish with any other fish species in Georgia waters. It may superficially resemble the banded (Enneacanthus obesus) and bluespotted (E. gloriosus) sunfishes, which differ in having only a shallow notch separating the spinous and soft-rayed portions of the dorsal fin and lacking the prominent dark bar extending through the anterior dorsal fin membranes. Habitat: Blackbanded sunfish are restricted to shallow, low-velocity, non-turbid waters of lakes, ponds, rivers and streams. They are strongly associated with aquatic plants, which provide habitat for foraging and cover. -

Suwannee River State Park

HISTORY AND NATURE SUWANNEE RIVER The park contains over 1,800 acres of natural STATE PARK Florida with many features such as sinks, streams, 3631 201st Path SUWANNEE RIVER springs, limestone outcroppings and the rivers. Live Oak, FL 32060 STATE PARK The park has an abundance of plant and animal 386-362-2746 species including gopher tortoise, fox, deer, song Where the scenic Withlacoochee birds, wildflowers and diverse native forests. The joins the historic Suwannee protected Gulf Sturgeon and other fishes and reptiles are abundant in the river. PARK GUIDELINES Early use by Native Americans dates back some • Hours are 8 a.m. until sunset, 365 days a year. 12,000 years. While under Spanish control, the • An entrance fee is required. passage of De Soto’s party occurred in 1540. During • All plants, animals and park property are 1818 Andrew Jackson lead American forces through protected. Collection, destruction or disturbance this area searching for Indian strongholds, believed is prohibited. responsible for raiding settlers. • Pets are permitted in designated areas only. Pets Vestiges of history in the park show how important must be kept on a handheld leash no longer the Suwannee River was to Florida history. One can than six feet and well-behaved at all times. find an earthworks mound built during the Civil • Fishing, boating and fires are allowed in War to defend the railroad crossing that supplied designated areas only. A Florida fishing license confederate troops. The Battle of Olustee in may be required. February 1864 turned back Union forces heading west to destroy this bridge. -

Streamflow Maps of Georgia's Major Rivers

GEORGIA STATE DIVISION OF CONSERVATION DEPARTMENT OF MINES, MINING AND GEOLOGY GARLAND PEYTON, Director THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Information Circular 21 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson United States Geological Survey Prepared cooperatively by the Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior, Washington, D. C. ATLANTA 1960 STREAMFLOW MAPS OF GEORGIA'S MAJOR RIVERS by M. T. Thomson Maps are commonly used to show the approximate rates of flow at all localities along the river systems. In addition to average flow, this collection of streamflow maps of Georgia's major rivers shows features such as low flows, flood flows, storage requirements, water power, the effects of storage reservoirs and power operations, and some comparisons of streamflows in different parts of the State. Most of the information shown on the streamflow maps was taken from "The Availability and use of Water in Georgia" by M. T. Thomson, S. M. Herrick, Eugene Brown, and others pub lished as Bulletin No. 65 in December 1956 by the Georgia Department of Mines, Mining and Geo logy. The average flows reported in that publication and sho\vn on these maps were for the years 1937-1955. That publication should be consulted for detailed information. More recent streamflow information may be obtained from the Atlanta District Office of the Surface Water Branch, Water Resources Division, U. S. Geological Survey, 805 Peachtree Street, N.E., Room 609, Atlanta 8, Georgia. In order to show the streamflows and other features clearly, the river locations are distorted slightly, their lengths are not to scale, and some features are shown by block-like patterns. -

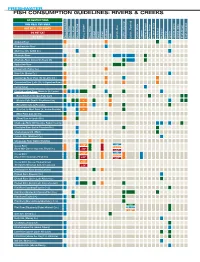

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Okefenokee Swamp Hydrology

OKEFENOKEE SWAMP HYDROLOGY Cynthia S. Loftin' AUTHOR: 'Graduate Research Assistant-Ph.D. Candidate, USGS-BRD Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0450. REFERENCE: Proceedings of the 1997 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held 20-22 March 1997, at the University of Georgia, Kathryn J. Hatcher, Editor, Institute of Ecology, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Abstract. The Okefenokee Swamp is one of North topographic relief is minimal The swamp is a bowl-like America's largest freshwater wetlands. Swamp hydrology depression in the landscape with the trend in ground surface is largely controlled by precipitation and elevation from 38.4 m at Kingfisher Landing in the evapotranspiration; regional topographic features of the Northeast to 33.0 m in the area where the Suwannee River swamp control surface water movements. Manipulations to exits the swamp in the West to 34.75 m at Ellicott's Mound the swamp topography and vegetation communities during in the Southeast near the St. Mary's River outflow. Within this century have affected water movement and variability the swamp are regional topographic highs on large sand- in parts of the swamp. Changes in swamp hydrology since based islands and lows in large prairies. The prairies also the construction of the Suwannee River Sill are generally contain local topographic highs on peat-based islands that restricted to the West Central area bounded by the Pocket, may rise a meter above the surrounding inundated peat Billy's Island, Craven's Island, Minnie's Island, and surface. -

Quick Reference Fact Sheet

Okefenokee at a Glance The Okefenokee Swamp is located in Ware, Charlton, and Clinch Counties, Georgia and Baker County, Florida. Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge was established by Executive Order in 1936. The Okefenokee Swamp covers 438,000 acres. It is 38 miles in length at its longest point by 25 miles in width at its widest point. The swamp is approximately 700 square miles. The Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is over 402,000 acres. The wilderness area consists of 353,981 acres and was created by the Okefenokee Wilderness Act of 1974 which is part of the Wilderness Preservation System. Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is the largest National Wildlife Refuge in the eastern United States. It is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service which is under the Department of the Interior. The Okefenokee Swamp is approximately 7000 years old. It is a vast peat-filled bog inside a huge, saucer-shaped depression that was once part of the ocean floor. The elevation of the swamp varies. There is a 25 foot drop from the northwest side to the southwest side. The range in elevation is from 128 feet above sea level on the northeast side to 103 feet on the southwest side. The vegetative indicator of the natural swamp line is the presence of the saw palmetto. The Suwannee River is the principle outlet of the swamp. The Suwannee flows from the west side of the swamp and empties into the Gulf of Mexico near Cedar Key, Florida. The Suwannee River is 280 miles long. A small area of the southeastern part of the swamp is drained by the St. -

Economic Analysis of Critical Habitat Designation for the Fat Threeridge, Shinyrayed Pocketbook, Gulf Moccasinshell, Ochlockonee

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF CRITICAL HABITAT DESIGNATION FOR THE FAT THREERIDGE, SHINYRAYED POCKETBOOK, GULF MOCCASINSHELL, OCHLOCKONEE MOCCASINSHELL, OVAL PIGTOE, CHIPOLA SLABSHELL, AND PURPLE BANKCLIMBER Draft Final Report | September 12, 2007 prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4401 N. Fairfax Drive Arlington, VA 22203 prepared by: Industrial Economics, Incorporated 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Draft – September 12, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES-1T SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION AND FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS 1-1 1.1 Purpose of the Economic Analysis 1-1 1.2 Background 1-2 1.3 Regulatory Alternatives 1-9 1.4 Threats to the Species and Habitat 1-9 1.5 Approach to Estimating Economic Effects 1-9 1.6 Scope of the Analysis 1-13 1.7 Analytic Time Frame 1-16 1.8 Information Sources 1-17 1.9 Structure of Report 1-18 SECTION 2 POTENTIAL CHANGES IN WATER USE AND MANAGEMENT FOR CONSERVATION OF THE SEVEN MUSSELS 2-1 2.1 Summary of Methods for Estimation of Economic Impacts Associated with Flow- Related Conservation Measures 2-2 2.2 Water Use in Proposed Critical Habitat Areas 2-3 2.3 Potential Changes in Water Use in the Flint River Basin 2-5 2.4 Potential Changes in Water Management in the Apalachicola River Complex (Unit 8) 2-10 2.5 Potential Changes in Water Management in the Santa Fe River Complex (Unit 11) 2-22 SECTION 3 POTENTIAL ECONOMIC IMPACTS RELATED TO CHANGES IN WATER USE AND MANAGEMENT 3-1 3.1 Summary 3-6 3.2 Potential Economic Impacts Related to Agricultural Water Uses 3-7 3.3 Potential Economic Impacts Related -

Aucilla River Paddling Guide

2«¬57B F ll o r ii d a D e s ii g n a tt e d P a d dWalluiki enengah T r aCaiippllss ¯ A u c ii ll ll a R ii v e r £19 £27 «¬259 ¤¤ Lamont «¬150 JEFFERSON MADISON A u c ii ll ll a R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p 2«¬57A Eridu TAYLOR «¬14 Designated Paddling Trail Wetlands Water Designated Paddling Trail Index 0 1 2 4 Miles A u c ii ll ll a R ii v e rr P a d d ll ii n g T rr a ii ll M a p ¯ Wal ker Sp ringsT ho - mas C ity Rd Lan i er Rd # 1: Herndon Landing !| N30.31754 W-83.81561 JEFFERSON MADISON l a c n O TAYLOR 7 5 2 R C # 3: Old Railroad Bridge !y N30.2799 W-83.8422 !| # 2 Reams Landing N30.172751 W-83.504424 d a e e r il v e G i v RR i t ll aa M iill #4, Jones Mill Creek cc N30.254567 W-83.897367 uu AA d a o R m ra T l Middle Aucilla !| a e Conservation Area n O O n e a l S Scout Rapids id e N30.2458 W-83.9143 4 1 R C e in L r r e e w v i o P R a l l i c u A Tower CR 680 !| #5, End of Trail, N30.2105 W-83.9218 Go ose P asture Aucilla Wildlife Co un Management Area ty R oa d 65 k 5 c rd o o F m y k m c Florida National Scenic Trail a o H R l l e w o Aucilla River Designated Paddling Trail P !| Canoe/Kayak Launch Conservation Lands 0 0.75 1.5 3 Miles Wetlands Aucilla River Paddling Trail Guide The Waterway With high limestone banks and an arching canopy of live oaks, cypress and other trees, the Aucilla River is as picturesque as it is wild. -

Status of Private Cypress Wetland Forests in Georgia

STATUS OF PRIVATE CYPRESS WETLAND FORESTS IN GEORGIA Alternatives for Conservation and Restoration ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We thank the United States Environmental Protection Agency for funding this project, and especially, Jennifer Derby and Tom Welborn for their dedication to conserving Georgia’s cypress resources. We are also grateful to Richard Harper, Jeffery Turner, and Tony Johnson of the U.S. Forest Service, Forest Inventory and Analysis, for their invaluable assistance and train- ing in the retrieval and analysis of the agency’s forest trend data. We thank the Riverkeepers of the Altamaha, Ogeechee, Satilla, and Savannah Rivers for their important contributions to this project. In addition, we wish to express our apprecia- tion to James Holland, the Altamaha Riverkeeper, for the many hours he spent arranging the Wilkinson County case study site visits and working with us in the field to document site conditions. We are grateful to the landowners of the Wilkinson County site for allowing us to evaluate their property and to Mr. Wyndell Berryhall for his assistance in the field. We also wish to thank all those who provided thoughtful review and comments on drafts of this report: Richard Harper, John Greis, Mark Brown, and Tony Johnson of the U.S. Forest Service; Rhett Jackson, Professor of Hydrology, Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia; Frank Green and James Johnson, Georgia Forestry Commission; James Jeter, Ala- bama Forestry Commission; Hughes Simpson, Texas Forest Service; John Swords, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; and Shaun Blocker, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Southern Environmental Law Center is a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting the health and environment of the Southeast (Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia). -

Coosa River Lake Lanier Georgia's Rural

GEORGIA’S HEADWATER STREAMS COOSA RIVER LAKE LANIER GEORGIA’S RURAL COMMUNITIES GEORGIA’S PUBLIC HEALTH CHATTAHOOCHEE RIVER OCMULGEE RIVER ALTAMAHA RIVER TERRY CREEK ST. SIMONS OKEFENOKEE SOUND SWAMP ST. MARYS RIVER 2019’s Worst Offenses Against GEORGIA’S WATER GEORGIA WATER COALITION’S DIRTY DOZEN A Call to Action The Georgia Water Coalition’s Dirty Dozen list highlights the politics, policies and issues that threaten the health of Georgia’s water and the well-being of 10 million Georgians. The purpose of the report is not to identify the state’s “most polluted places.” Instead the report is a call to action for Georgia’s leaders and its citizens to solve ongoing pollution problems, eliminate potential threats to Georgia’s water and correct state and federal policies and actions that lead to polluted water. Unfortunately, this year’s report includes seven issues that are making return visits to this inauspicious list. Topping that category is pollution of the Altamaha River from the Rayonier Advanced Materials (RAM) chemical pulp mill in Jesup. The facility is making a record seventh appearance in the Dirty Dozen report because pollution from the mill continues. Next year, Georgia’s Environmental Protection Division (EPD) will issue a new pollution control permit for the facility, but if EPD’s actions in recent years are any indication, it seems unlikely that this new permit will fix this ongoing pollution problem. The state agency has repeatedly defended the existing and weak The Georgia Water Coalition’s Dirty Dozen report is a pollution control permit and last year took the extraordinary step of call to action for Georgia’s leaders and citizens to solve changing state laws to make it easier for RAM to continue polluting ongoing pollution problems, eliminate potential threats Georgia’s largest river.