Status of Private Cypress Wetland Forests in Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghosts of the Western Glades Just Northwest of Everglades National Park Lies Probably the Wildest, Least Disturbed Natural Area in All of Florida

Discovering the Ghosts of the Western Glades Just Northwest of Everglades National Park lies probably the wildest, least disturbed natural area in all of Florida. Referred to as the Western Everglades (or Western Glades), it includes Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve and Big Cypress National Preserve. Environmentalists that pushed for the creation of Everglades National Park originally wanted this area included in it. But politics and lack of funds prevented this. Several decades passed before Big Cypress National Preserve was born in 1974. Preserves have slightly less restrictive rules than national parks. So how is the Big Cypress Swamp distinct from the Everglades? Even though both habitats have many similarities (sawgrass prairies & tree islands, for instance), the Big Cypress Swamp is generally 1-2 feet higher in elevation. Also, it has a mainly southwesterly flow of water, dumping into the “ten thousand islands” area on Florida’s Gulf of Mexico coast and serving as an important watershed for the River of Grass to the south. Then, of course, there are the cypress trees. Cypress Trees Not surprisingly, of course, is the fact that the Big Cypress Swamp has about 1/3 of its area covered in cypress trees. Mostly they are the small “dwarf pond cypress” trees. (“Big” refers to the large mass of land not the size of the trees.) A few locations, however, still do boast the impressive towering “bald cypress” trees but most of those were logged out between the years 1913 - 1948. Ridge & Slough Topography Topography simply means the relief (or elevation variances) of any particular area of land. -

Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River Named Among America's

Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River named Among America’s Most Endangered Rivers of 2020 Mining threatens, fish and wildlife habitat; wetlands; water quality and flow Contact: Ben Emanuel, American Rivers, 706-340-8868 Christian Hunt, Defenders of Wildlife 828-417-0862 Rena Ann Peck, Georgia River Network, 404-395-6250 Alice Miller Keyes, One Hundred Miles, 912-230-6494 Alex Kearns, St. Marys EarthKeepers, 912-322-7367 Washington, D.C. –American Rivers today named the Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River among America’s Most Endangered Rivers®, citing the threat titanium mining would pose to the waterways’ clean water, wetlands and wildlife habitat. American Rivers and its partners called on the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and other permitting agencies to deny any proposals that risk the long-term protection of the Okefenokee Swamp and St. Marys River. “America’s Most Endangered Rivers is a call to action,” said Ben Emanuel, Atlanta- based Clean Water Supply Director with American Rivers. “Some places are simply too precious to allow risky mining operations, and the edge of the unique Okefenokee Swamp is one. The Army Corps of Engineers must deny the permit to save this national treasure.” The annual America’s Most Endangered Rivers report is a list of rivers at a crossroads, where key decisions in the coming months will determine the rivers’ fates. Over the years, the report has helped spur many successes including the removal of outdated dams, the protection of rivers with Wild and Scenic designations, and the prevention of harmful development and pollution. Rena Ann Peck, Executive Director of Georgia River Network, explains "The Okefenokee Swamp is like the heart of the regional Floridan aquifer system in southeast Georgia and northeast Florida. -

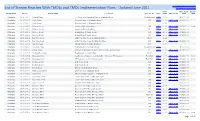

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Plant Succession on Burned Areas in Okefenokee Swamp Following the Fires of 1954 and 1955 EUGENE CYPERT Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge U.S

Plant Succession on Burned Areas in Okefenokee Swamp Following the Fires of 1954 and 1955 EUGENE CYPERT Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and 'Wildlife Waycross, GA 31501 INTRODUCTION IN 1954 and 1955, during an extreme drought, five major fires occurred in Okefenokee Swamp. These fires swept over approximately 318,000 acres of the swamp and 140,000 acres of the adjacent upland. In some areas in the swamp, the burning was severe enough to kill most of the timber and the understory vegetation and burn out pockets in the peat bed. Burns of this severity were usually small and spotty. Over most of the swamp, the burns were surface fires which generally killed most of the underbrush but rarely burned deep enough into the peat bed to kill the larger trees. In many places the swamp fires swept over lightly, burning surface duff and killing only the smaller underbrush. Some areas were missed entirely. On the upland adjacent to the swamp, the fires were very de structive, killing most of the pine timber on the 140,000 acres burned over. The destruction of pine forests on the upland and the severe 199 EUGENE CYPERT burns in the swamp caused considerable concern among conservation ists and neighboring land owners. It was believed desirable to learn something of the succession of vegetation on some of the more severely burned areas. Such knowl edge would add to an understanding of the ecology and history of the swamp and to an understanding of the relation that fires may have to swamp wildlife. -

Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves Ben Parten Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2017 "Somewhere Toward Freedom:" Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves Ben Parten Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Parten, Ben, ""Somewhere Toward Freedom:" Sherman's March and Georgia's Refugee Slaves" (2017). All Theses. 2665. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2665 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SOMEWHERE TOWARD FREEDOM:” SHERMAN’S MARCH AND GEORGIA’S REFUGEE SLAVES A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts History by Ben Parten May 2017 Accepted by: Dr. Vernon Burton, Committee Chair Dr. Lee Wilson Dr. Rod Andrew ABSTRACT When General William T. Sherman’s army marched through Georgia during the American Civil War, it did not travel alone. As many as 17,000 refugee slaves followed his army to the coast; as many, if not more, fled to the army but decided to stay on their plantations rather than march on. This study seeks to understand Sherman’s march from their point of view. It argues that through their refugee experiences, Georgia’s refugee slaves transformed the march into one for their own freedom and citizenship. Such a transformation would not be easy. Not only did the refugees have to brave the physical challenges of life on the march, they had to also exist within a war waged by white men. -

Limpkin Aramus Guarauna Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: Blimp Order: Gruiformes ITIS Species Code: 176197 Family: Aramidae Natureserve Element Code: ABNMJ01010

Limpkin Aramus guarauna Taxa: Avian SE-GAP Spp Code: bLIMP Order: Gruiformes ITIS Species Code: 176197 Family: Aramidae NatureServe Element Code: ABNMJ01010 KNOWN RANGE: PREDICTED HABITAT: P:\Proj1\SEGap P:\Proj1\SEGap Range Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Range_bLIMP.pdf Predicted Habitat Map Link: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/maps/SE_Dist_bLIMP.pdf GAP Online Tool Link: http://www.gapserve.ncsu.edu/segap/segap/index2.php?species=bLIMP Data Download: http://www.basic.ncsu.edu/segap/datazip/region/vert/bLIMP_se00.zip PROTECTION STATUS: Reported on March 14, 2011 Federal Status: --- State Status: FL (SSC) NS Global Rank: G5 NS State Rank: AL (SNA), FL (S3), GA (S1S2), IL (SNA), MD (SNA), MS (SNA), NC (SNA), TX (SNA), VA (SNA), NS (SNA) bLIMP Page 1 of 4 SUMMARY OF PREDICTED HABITAT BY MANAGMENT AND GAP PROTECTION STATUS: US FWS US Forest Service Tenn. Valley Author. US DOD/ACOE ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 34,779.2 < 1 120.6 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 2 18,984.4 < 1 26,563.7 < 1 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 3 0.0 0 154,688.7 2 0.0 0 31,698.2 < 1 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 53,763.7 < 1 181,373.0 3 0.0 0 31,698.2 < 1 US Dept. of Energy US Nat. Park Service NOAA Other Federal Lands ha % ha % ha % ha % Status 1 0.0 0 362,645.8 5 0.0 0 8,464.4 < 1 Status 2 0.0 0 3,173.0 < 1 12,062.5 < 1 77.1 < 1 Status 3 0.0 0 270,295.1 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 Status 4 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 0.0 0 Total 0.0 0 636,113.9 9 12,062.5 < 1 8,541.5 < 1 Native Am. -

* This Is an Excerpt from Protected Animals of Georgia Published By

Common Name: BLACKBANDED SUNFISH Scientific Name: Enneacanthus chaetodon Other Commonly Used Names: none Previously Used Scientific Names: none Family: Centrarchidae Rarity Ranks: G4/S1 State Legal Status: Endangered Federal Legal Status: Not Listed Description: The blackbanded sunfish is a small, laterally compressed and deep-bodied species reaching a maximum total length of 100 mm (4 inches). There is a prominent notch separating the spinous and soft-rayed portions of the dorsal fin. It is distinctively marked with 5-6 black bars along the sides that extend from the dorsum to the venter. The first of these bars passes through the eye, and the third extends through the first three membranes of the spinous dorsal fin to the upper edge of the fin. No other sunfish has this barring pattern. The blackbanded sunfish is also very colorful with black vertical bars, olive-brown to variegated-brown on the dorsum and upper sides, and orange-copper marking the leading edge of the pelvic fins and the irises. Similar Species: The small body size and distinctive color pattern make it difficult to confuse the blackbanded sunfish with any other fish species in Georgia waters. It may superficially resemble the banded (Enneacanthus obesus) and bluespotted (E. gloriosus) sunfishes, which differ in having only a shallow notch separating the spinous and soft-rayed portions of the dorsal fin and lacking the prominent dark bar extending through the anterior dorsal fin membranes. Habitat: Blackbanded sunfish are restricted to shallow, low-velocity, non-turbid waters of lakes, ponds, rivers and streams. They are strongly associated with aquatic plants, which provide habitat for foraging and cover. -

Evaluating the Functional Response of Isolated Cypress Domes to Groundwater Alteration in West-Central Florida

Evaluating the functional response of isolated cypress domes to groundwater alteration in west-central Florida by Megan Kristine Bartholomew A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama May 6, 2017 Copyright 2017 by Megan Bartholomew Approved by Christopher Anderson, Chair, Professor of Wetland Ecology Robert Boyd, Professor of Plant Ecology Jacob Berkowitz, Research Soil Scientist Abstract The hydrology of a wetland is the single most important determinant of its function and slight alterations can lead to significant changes in plant communities and biogeochemistry within the wetland. Therefore, understanding the influence of hydrology on vegetative and soil processes is pivotal to restoration efforts. This study investigated how hydrologic alteration and recovery influenced wetland vegetation and soil processes in Starkey Wilderness Park (SWP), a well-field in west-central Florida. Vegetation responses to groundwater alterations were observed using long term species and hydrologic data collected from SWP. The results from the vegetation study suggest that hydrologic recovery has restored vegetative functions and measures, such as species richness and hydrophytic assemblages, in a relatively short (5-7 year) period. However, differences in species composition and community variation persist in wetlands of various degrees of hydrologic alterations. A field study was also conducted to determine how hydrologic alterations continue to affect wetland decomposition rates and other soil processes. After eight years of hydrologic recovery, altered wetlands experienced faster decomposition than reference wetlands and rates seemed to be linked to differences in both inundation and percent soil organic matter. -

July 3-9, 2011

Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Resources Division Law Enforcement Section Field Operations Weekly Report July 3-9, 2011 This report is a broad sampling of events that have taken place in the past week, but does not include all actions taken by the Law Enforcement Section. Region I- Calhoun (Northwest) FLOYD COUNTY On Sunday June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore was working along the Etowah River in Rome and overheard radio traffic from Rome PD about a vehicle getting broken into at the Etowah River boat ramp. Cpl. Elmore responded to the boat ramp and assisted Rome PD officer. Cpl. Elmore located one of the suspects hiding in the woods and the other suspect came out of the river. Three juvenile suspects were detained and charged with entering an auto and criminal damage to property by Rome PD. On June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore was at the Heritage Park boat ramp on the Coosa River in Rome when he was approached by a parent of four teenagers that were caught in a storm on the Etowah River. Cpl. Elmore went to get his patrol vessel and while enroute to the Etowah River boat ramp the four teens called the parents and advised they had gotten out of the river safely and were waiting on a ride on Turner Chapel Rd. On the night of June 26th, Cpl. Shawn Elmore received a call from Floyd E911 about 3 adults and a 3 year-old child stranded on the Etowah River. Cpl. Elmore responded to the scene and assisted Rome/Floyd Fire with a search of the river and the four were located and safely returned to their vehicle. -

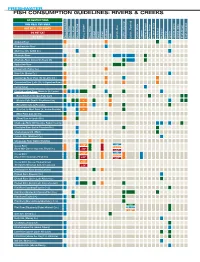

Fish Consumption Guidelines: Rivers & Creeks

FRESHWATER FISH CONSUMPTION GUIDELINES: RIVERS & CREEKS NO RESTRICTIONS ONE MEAL PER WEEK ONE MEAL PER MONTH DO NOT EAT NO DATA Bass, LargemouthBass, Other Bass, Shoal Bass, Spotted Bass, Striped Bass, White Bass, Bluegill Bowfin Buffalo Bullhead Carp Catfish, Blue Catfish, Channel Catfish,Flathead Catfish, White Crappie StripedMullet, Perch, Yellow Chain Pickerel, Redbreast Redhorse Redear Sucker Green Sunfish, Sunfish, Other Brown Trout, Rainbow Trout, Alapaha River Alapahoochee River Allatoona Crk. (Cobb Co.) Altamaha River Altamaha River (below US Route 25) Apalachee River Beaver Crk. (Taylor Co.) Brier Crk. (Burke Co.) Canoochee River (Hwy 192 to Lotts Crk.) Canoochee River (Lotts Crk. to Ogeechee River) Casey Canal Chattahoochee River (Helen to Lk. Lanier) (Buford Dam to Morgan Falls Dam) (Morgan Falls Dam to Peachtree Crk.) * (Peachtree Crk. to Pea Crk.) * (Pea Crk. to West Point Lk., below Franklin) * (West Point dam to I-85) (Oliver Dam to Upatoi Crk.) Chattooga River (NE Georgia, Rabun County) Chestatee River (below Tesnatee Riv.) Chickamauga Crk. (West) Cohulla Crk. (Whitfield Co.) Conasauga River (below Stateline) <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (River Mile Zero to Hwy 100, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" <18" Coosa River <20" 18 –32" (Hwy 100 to Stateline, Floyd Co.) ≥20" >32" Coosa River (Coosa, Etowah below <20" Thompson-Weinman dam, Oostanaula) ≥20" Coosawattee River (below Carters) Etowah River (Dawson Co.) Etowah River (above Lake Allatoona) Etowah River (below Lake Allatoona dam) Flint River (Spalding/Fayette Cos.) Flint River (Meriwether/Upson/Pike Cos.) Flint River (Taylor Co.) Flint River (Macon/Dooly/Worth/Lee Cos.) <16" Flint River (Dougherty/Baker Mitchell Cos.) 16–30" >30" Gum Crk. -

Okefenokee Swamp Hydrology

OKEFENOKEE SWAMP HYDROLOGY Cynthia S. Loftin' AUTHOR: 'Graduate Research Assistant-Ph.D. Candidate, USGS-BRD Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611-0450. REFERENCE: Proceedings of the 1997 Georgia Water Resources Conference, held 20-22 March 1997, at the University of Georgia, Kathryn J. Hatcher, Editor, Institute of Ecology, The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia. Abstract. The Okefenokee Swamp is one of North topographic relief is minimal The swamp is a bowl-like America's largest freshwater wetlands. Swamp hydrology depression in the landscape with the trend in ground surface is largely controlled by precipitation and elevation from 38.4 m at Kingfisher Landing in the evapotranspiration; regional topographic features of the Northeast to 33.0 m in the area where the Suwannee River swamp control surface water movements. Manipulations to exits the swamp in the West to 34.75 m at Ellicott's Mound the swamp topography and vegetation communities during in the Southeast near the St. Mary's River outflow. Within this century have affected water movement and variability the swamp are regional topographic highs on large sand- in parts of the swamp. Changes in swamp hydrology since based islands and lows in large prairies. The prairies also the construction of the Suwannee River Sill are generally contain local topographic highs on peat-based islands that restricted to the West Central area bounded by the Pocket, may rise a meter above the surrounding inundated peat Billy's Island, Craven's Island, Minnie's Island, and surface. -

Quick Reference Fact Sheet

Okefenokee at a Glance The Okefenokee Swamp is located in Ware, Charlton, and Clinch Counties, Georgia and Baker County, Florida. Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge was established by Executive Order in 1936. The Okefenokee Swamp covers 438,000 acres. It is 38 miles in length at its longest point by 25 miles in width at its widest point. The swamp is approximately 700 square miles. The Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is over 402,000 acres. The wilderness area consists of 353,981 acres and was created by the Okefenokee Wilderness Act of 1974 which is part of the Wilderness Preservation System. Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge is the largest National Wildlife Refuge in the eastern United States. It is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service which is under the Department of the Interior. The Okefenokee Swamp is approximately 7000 years old. It is a vast peat-filled bog inside a huge, saucer-shaped depression that was once part of the ocean floor. The elevation of the swamp varies. There is a 25 foot drop from the northwest side to the southwest side. The range in elevation is from 128 feet above sea level on the northeast side to 103 feet on the southwest side. The vegetative indicator of the natural swamp line is the presence of the saw palmetto. The Suwannee River is the principle outlet of the swamp. The Suwannee flows from the west side of the swamp and empties into the Gulf of Mexico near Cedar Key, Florida. The Suwannee River is 280 miles long. A small area of the southeastern part of the swamp is drained by the St.