Cell Culture-Based Profiling Across Mammals Reveals DNA Repair And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sanjay Kumar Gupta

The human CCHC-type Zinc Finger Nucleic Acid Binding Protein (CNBP) binds to the G-rich elements in target mRNA coding sequences and promotes translation Das humane CCHC-Typ-Zinkfinger-Nukleinsäure-Binde-Protein (CNBP) bindet an G-reiche Elemente in der kodierenden Sequenz seiner Ziel-mRNAs und fördert deren Translation Doctoral thesis for a doctoral degree at the Graduate School of Life Sciences, Julius-Maximilians-Universität WürzBurg, Section: Biomedicine suBmitted By Sanjay Kumar Gupta from Varanasi, India WürzBurg, 2016 1 Submitted on: …………………………………………………………..…….. Office stamp Members of the Promotionskomitee: Chairperson: Prof. Dr. Alexander Buchberger Primary Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Juranek Supervisor (Second): Prof. Dr. Utz Fischer Supervisor (Third): Dr. Markus Landthaler Date of Public Defence: …………………………………………….………… Date of Receipt of Certificates: ………………………………………………. 2 Summary The genetic information encoded with in the genes are transcribed and translated to give rise to the functional proteins, which are building block of a cell. At first, it was thought that the regulation of gene expression particularly occurs at the level of transcription By various transcription factors. Recent discoveries have shown the vital role of gene regulation at the level of RNA also known as post-transcriptional gene regulation (PTGR). Apart from non-coding RNAs e.g. micro RNAs, various RNA Binding proteins (RBPs) play essential role in PTGR. RBPs have been implicated in different stages of mRNA life cycle ranging from splicing, processing, transport, localization and decay. In last 20 years studies have shown the presence of hundreds of RBPs across eukaryotic systems many of which are widely conserved. Given the rising numBer of RBPs and their link to human diseases it is quite evident that RBPs have major role in cellular processes and their regulation. -

Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 25, 2021 T + is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology , 34 of which you can access for free at: 2016; 197:1477-1488; Prepublished online 1 July from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication 2016; doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600589 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477 Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8 Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. Waugh, Sonia M. Leach, Brandon L. Moore, Tullia C. Bruno, Jonathan D. Buhrman and Jill E. Slansky J Immunol cites 95 articles Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2016/07/01/jimmunol.160058 9.DCSupplemental This article http://www.jimmunol.org/content/197/4/1477.full#ref-list-1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material References Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2016 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 25, 2021. The Journal of Immunology Molecular Profile of Tumor-Specific CD8+ T Cell Hypofunction in a Transplantable Murine Cancer Model Katherine A. -

The Zinc-Finger Protein CNBP Is Required for Forebrain Formation In

Development 130, 1367-1379 1367 © 2003 The Company of Biologists Ltd doi:10.1242/dev.00349 The zinc-finger protein CNBP is required for forebrain formation in the mouse Wei Chen1,2, Yuqiong Liang1, Wenjie Deng1, Ken Shimizu1, Amir M. Ashique1,2, En Li3 and Yi-Ping Li1,2,* 1Department of Cytokine Biology, The Forsyth Institute, Boston, MA 02115, USA 2Harvard-Forsyth Department of Oral Biology, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, MA 02115, USA 3Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 19 December 2002 SUMMARY Mouse mutants have allowed us to gain significant insight (AME), headfolds and forebrain. In Cnbp–/– embryos, the into axis development. However, much remains to be visceral endoderm remains in the distal tip of the conceptus learned about the cellular and molecular basis of early and the ADE fails to form, whereas the node and notochord forebrain patterning. We describe a lethal mutation mouse form normally. A substantial reduction in cell proliferation strain generated using promoter-trap mutagenesis. The was observed in the anterior regions of Cnbp–/– embryos at mutants exhibit severe forebrain truncation in homozygous gastrulation and neural-fold stages. In these regions, Myc mouse embryos and various craniofacial defects in expression was absent, indicating CNBP targets Myc in heterozygotes. We show that the defects are caused by rostral head formation. Our findings demonstrate that disruption of the gene encoding cellular nucleic acid Cnbp is essential for the forebrain induction and binding protein (CNBP); Cnbp transgenic mice were able specification. -

Transcriptome Analyses of Rhesus Monkey Pre-Implantation Embryos Reveal A

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Transcriptome analyses of rhesus monkey pre-implantation embryos reveal a reduced capacity for DNA double strand break (DSB) repair in primate oocytes and early embryos Xinyi Wang 1,3,4,5*, Denghui Liu 2,4*, Dajian He 1,3,4,5, Shengbao Suo 2,4, Xian Xia 2,4, Xiechao He1,3,6, Jing-Dong J. Han2#, Ping Zheng1,3,6# Running title: reduced DNA DSB repair in monkey early embryos Affiliations: 1 State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China 2 Key Laboratory of Computational Biology, CAS Center for Excellence in Molecular Cell Science, Collaborative Innovation Center for Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences-Max Planck Partner Institute for Computational Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200031, China 3 Yunnan Key Laboratory of Animal Reproduction, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650223, China 4 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 5 Kunming College of Life Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650204, China 6 Primate Research Center, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, 650223, China * Xinyi Wang and Denghui Liu contributed equally to this work 1 Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press # Correspondence: Jing-Dong J. Han, Email: [email protected]; Ping Zheng, Email: [email protected] Key words: rhesus monkey, pre-implantation embryo, DNA damage 2 Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 23, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press ABSTRACT Pre-implantation embryogenesis encompasses several critical events including genome reprogramming, zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and cell fate commitment. -

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Mig-6 Controls EGFR Trafficking and Suppresses Gliomagenesis

Mig-6 controls EGFR trafficking and suppresses gliomagenesis Haoqiang Yinga,1, Hongwu Zhenga,1, Kenneth Scotta, Ruprecht Wiedemeyera, Haiyan Yana, Carol Lima, Joseph Huanga, Sabin Dhakala, Elena Ivanovab, Yonghong Xiaob,HaileiZhangb,JianHua, Jayne M. Stommela, Michelle A. Leea, An-Jou Chena, Ji-Hye Paika,OresteSegattoc, Cameron Brennand,e, Lisa A. Elferinkf,Y.AlanWanga,b, Lynda China,b,g, and Ronald A. DePinhoa,b,h,2 aDepartment of Medical Oncology, bBelfer Institute for Applied Cancer Science, Belfer Foundation Institute for Innovative Cancer Science, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; cLaboratory of Immunology, Istituto Regina Elena, Rome 00158, Italy; dHuman Oncology and Pathogenesis Program and eDepartment of Neurosurgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065; fDepartment of Neuroscience and Cell Biology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555; gDepartment of Dermatology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; and hDepartment of Medicine and Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 Edited* by Webster K. Cavenee, Ludwig Institute, University of California, La Jolla, CA, and approved March 8, 2010 (received for review December 23, 2009) Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and lethal structural aberrations that serve as a key pathological driving primary brain cancer that is driven by aberrant signaling of growth force for tumor progression and many of them remain to be factor receptors, particularly the epidermal growth factor receptor characterized (6, 7). GBM possesses a highly rearranged genome (EGFR). EGFR signaling is tightly regulated by receptor endocytosis and high-resolution genome analysis has uncovered myriad and lysosome-mediated degradation, although the molecular somatic alterations on the genomic and epigenetic levels (2, 3). -

Epigenetic Mechanisms of Lncrnas Binding to Protein in Carcinogenesis

cancers Review Epigenetic Mechanisms of LncRNAs Binding to Protein in Carcinogenesis Tae-Jin Shin, Kang-Hoon Lee and Je-Yoel Cho * Department of Biochemistry, BK21 Plus and Research Institute for Veterinary Science, School of Veterinary Medicine, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea; [email protected] (T.-J.S.); [email protected] (K.-H.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-02-800-1268 Received: 21 September 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 11 October 2020 Simple Summary: The functional analysis of lncRNA, which has recently been investigated in various fields of biological research, is critical to understanding the delicate control of cells and the occurrence of diseases. The interaction between proteins and lncRNA, which has been found to be a major mechanism, has been reported to play an important role in cancer development and progress. This review thus organized the lncRNAs and related proteins involved in the cancer process, from carcinogenesis to metastasis and resistance to chemotherapy, to better understand cancer and to further develop new treatments for it. This will provide a new perspective on clinical cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Abstract: Epigenetic dysregulation is an important feature for cancer initiation and progression. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts that stably present as RNA forms with no translated protein and have lengths larger than 200 nucleotides. LncRNA can epigenetically regulate either oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes. Nowadays, the combined research of lncRNA plus protein analysis is gaining more attention. LncRNA controls gene expression directly by binding to transcription factors of target genes and indirectly by complexing with other proteins to bind to target proteins and cause protein degradation, reduced protein stability, or interference with the binding of other proteins. -

Genetic and Genomic Analysis of Hyperlipidemia, Obesity and Diabetes Using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/Jngj) F2 Mice

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Nutrition Publications and Other Works Nutrition 12-19-2010 Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P. Stewart Marshall University Hyoung Y. Kim University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Arnold M. Saxton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Jung H. Kim Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nutrpubs Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-713 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stewart et al. BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/11/713 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P Stewart1, Hyoung Yon Kim2, Arnold M Saxton3, Jung Han Kim1* Abstract Background: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes in humans and is closely associated with dyslipidemia and obesity that magnifies the mortality and morbidity related to T2D. The genetic contribution to human T2D and related metabolic disorders is evident, and mostly follows polygenic inheritance. The TALLYHO/ JngJ (TH) mice are a polygenic model for T2D characterized by obesity, hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose uptake and tolerance, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. -

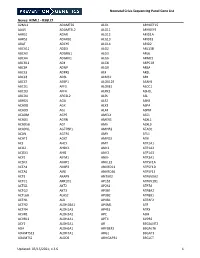

Transcriptome-Wide Profiling of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Transcriptome-wide Profling of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Patients Reveal Important Long noncoding RNA molecular signatures Santhilal Subhash 2,8, Norman Kalmbach3, Florian Wegner4, Susanne Petri4, Torsten Glomb5, Oliver Dittrich-Breiholz5, Caiquan Huang1, Kiran Kumar Bali6, Wolfram S. Kunz7, Amir Samii1, Helmut Bertalanfy1, Chandrasekhar Kanduri2* & Souvik Kar1,8* Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are low-fow vascular malformations in the brain associated with recurrent hemorrhage and seizures. The current treatment of CCMs relies solely on surgical intervention. Henceforth, alternative non-invasive therapies are urgently needed to help prevent subsequent hemorrhagic episodes. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) belong to the class of non-coding RNAs and are known to regulate gene transcription and involved in chromatin remodeling via various mechanism. Despite accumulating evidence demonstrating the role of lncRNAs in cerebrovascular disorders, their identifcation in CCMs pathology remains unknown. The objective of the current study was to identify lncRNAs associated with CCMs pathogenesis using patient cohorts having 10 CCM patients and 4 controls from brain. Executing next generation sequencing, we performed whole transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis and identifed 1,967 lncRNAs and 4,928 protein coding genes (PCGs) to be diferentially expressed in CCMs patients. Among these, we selected top 6 diferentially expressed lncRNAs each having signifcant correlative expression with more than 100 diferentially expressed PCGs. The diferential expression status of the top lncRNAs, SMIM25 and LBX2-AS1 in CCMs was further confrmed by qRT-PCR analysis. Additionally, gene set enrichment analysis of correlated PCGs revealed critical pathways related to vascular signaling and important biological processes relevant to CCMs pathophysiology. -

Detection of Pro Angiogenic and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients With

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Detection of pro angiogenic and infammatory biomarkers in patients with CKD Diana Jalal1,2,3*, Bridget Sanford4, Brandon Renner5, Patrick Ten Eyck6, Jennifer Laskowski5, James Cooper5, Mingyao Sun1, Yousef Zakharia7, Douglas Spitz7,9, Ayotunde Dokun8, Massimo Attanasio1, Kenneth Jones10 & Joshua M. Thurman5 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the most common cause of death in patients with native and post-transplant chronic kidney disease (CKD). To identify new biomarkers of vascular injury and infammation, we analyzed the proteome of plasma and circulating extracellular vesicles (EVs) in native and post-transplant CKD patients utilizing an aptamer-based assay. Proteins of angiogenesis were signifcantly higher in native and post-transplant CKD patients versus healthy controls. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) indicated Ephrin receptor signaling, serine biosynthesis, and transforming growth factor-β as the top pathways activated in both CKD groups. Pro-infammatory proteins were signifcantly higher only in the EVs of native CKD patients. IPA indicated acute phase response signaling, insulin-like growth factor-1, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-6 pathway activation. These data indicate that pathways of angiogenesis and infammation are activated in CKD patients’ plasma and EVs, respectively. The pathways common in both native and post-transplant CKD may signal similar mechanisms of CVD. Approximately one in 10 individuals has chronic kidney disease (CKD) rendering CKD one of the most common diseases worldwide1. CKD is associated with a high burden of morbidity in the form of end stage kidney disease (ESKD) requiring dialysis or transplantation 2. Furthermore, patients with CKD are at signifcantly increased risk of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD)3,4. -

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2