Detection of Pro Angiogenic and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Profiling of Transcripts and Proteins Modulated by the E7 Oncogene in the Lung Tissue of E7-Tg Mice by the Omics Approach

MOLECULAR MEDICINE REPORTS 2: 129-137, 2009 129 Profiling of transcripts and proteins modulated by the E7 oncogene in the lung tissue of E7-Tg mice by the omics approach EUNJIN KIM1*, JEONGWOO KANG1,3*, MINCHUL CHO1, SOJUNG LEE1, EUNHEE SEO1, HEESOOK CHOI1, YUMI KIM1, JUNGHEE KIM1, KUM YONG KANG2, KWANG PYO KIM2, JAEYONG HAN3, YHUNYHONG SHEEN4, YOUNG NA YUM5, SUE-NIE PARK5 and DO-YOUNG YOON1 Departments of 1Bioscience and Biotechnology, and 2Molecular Biotechnology, Konkuk University, Hwayang-dong 1, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-701; 3Laboratory of Animal Genetic Engineering, Department of Food and Animal Biotechnology, Seoul National University, Seoul 151-742; 4School of Pharmacy, Ewha Womans University, Seoul 120-750; 5Korea Food and Drug Administration, #194 Tongil-ro, Eunpyung-gu, Seoul 122-704, Korea Received August 18, 2008; Accepted November 10, 2008 DOI: 10.3892/mmr_00000073 Abstract. The E6 and E7 oncoproteins of human papilloma suggest that the E7 oncogene modulates the expression levels virus (HPV) type 16 have been known to cooperatively induce of cell cycle-related (cyclin B1, cyclin E2) and cell adhesion- the immortalization and transformation of primary keratino- and migration-related (actinin ·1, CD166) factors, which may cytes. We established an E7 transgenic mouse model to play important roles in cellular transformation in cancer. In screen HPV-related biomakers using the omics approach. addition, the solubilization of the rigid intermediate filament The methods used to identify HPV-modulated factors were network by specific proteolysis mediated via up-regulating genomics analysis by microarray using the Affymetrix 430 gelsolin and down-regulating cofilin-1, as well as increased 2.0 array to screen E7-modulated genes, and proteomics levels of endoplasmic reticulum protein calnexin with chap- analysis using nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS to screen E7-modulated erone functions, might also be involved in E7-lung epithelial proteins with the lung tissue of E7 transgenic mice. -

Epha Receptors and Ephrin-A Ligands Are Upregulated by Monocytic

Mukai et al. BMC Cell Biology (2017) 18:28 DOI 10.1186/s12860-017-0144-x RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access EphA receptors and ephrin-A ligands are upregulated by monocytic differentiation/ maturation and promote cell adhesion and protrusion formation in HL60 monocytes Midori Mukai, Norihiko Suruga, Noritaka Saeki and Kazushige Ogawa* Abstract Background: Eph signaling is known to induce contrasting cell behaviors such as promoting and inhibiting cell adhesion/ spreading by altering F-actin organization and influencing integrin activities. We have previously demonstrated that EphA2 stimulation by ephrin-A1 promotes cell adhesion through interaction with integrins and integrin ligands in two monocyte/ macrophage cell lines. Although mature mononuclear leukocytes express several members of the EphA/ephrin-A subclass, their expression has not been examined in monocytes undergoing during differentiation and maturation. Results: Using RT-PCR, we have shown that EphA2, ephrin-A1, and ephrin-A2 expression was upregulated in murine bone marrow mononuclear cells during monocyte maturation. Moreover, EphA2 and EphA4 expression was induced, and ephrin-A4 expression was upregulated, in a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line, HL60, along with monocyte differentiation toward the classical CD14++CD16− monocyte subset. Using RT-PCR and flow cytometry, we have also shown that expression levels of αL, αM, αX, and β2 integrin subunits were upregulated in HL60 cells along with monocyte differentiation while those of α4, α5, α6, and β1 subunits were unchanged. Using a cell attachment stripe assay, we have shown that stimulation by EphA as well as ephrin-A, likely promoted adhesion to an integrin ligand- coated surface in HL60 monocytes. Moreover, EphA and ephrin-A stimulation likely promoted the formation of protrusions in HL60 monocytes. -

Expression Tissue

The Journal of Immunology Killer Cell Ig-Like Receptor and Leukocyte Ig-Like Receptor Transgenic Mice Exhibit Tissue- and Cell-Specific Transgene Expression1 Danny Belkin,* Michaela Torkar,* Chiwen Chang,* Roland Barten,* Mauro Tolaini,† Anja Haude,* Rachel Allen,* Michael J. Wilson,* Dimitris Kioussis,† and John Trowsdale2* To generate an experimental model for exploring the function, expression pattern, and developmental regulation of human Ig-like activating and inhibitory receptors, we have generated transgenic mice using two human genomic clones: 52N12 (a 150-Kb clone encompassing the leukocyte Ig-like receptor (LILR)B1 (ILT2), LILRB4 (ILT3), and LILRA1 (LIR6) genes) and 1060P11 (a 160-Kb clone that contains ten killer cell Ig-like receptor (KIR) genes). Both the KIR and LILR families are encoded within the leukocyte receptor complex, and are involved in immune modulation. We have also produced a novel mAb to LILRA1 to facilitate expression studies. The LILR transgenes were expressed in a similar, but not identical, pattern to that observed in humans: LILRB1 was expressed in B cells, most NK cells, and a small number of T cells; LILRB4 was expressed in a B cell subset; and LILRA1 was found on a ring of cells surrounding B cell areas on spleen sections, consistent with other data showing monocyte/macrophage expression. KIR transgenic mice showed KIR2DL2 expression on a subset of NK cells and T cells, similar to the pattern seen in humans, and expression of KIR2DL4, KIR3DS1, and KIR2DL5 by splenic NK cells. These observations indicate that linked regulatory elements within the genomic clones are sufficient to allow appropriate expression of KIRs in mice, and illustrate that the presence of the natural ligands for these receptors, in the form of human MHC class I proteins, is not necessary for the expression of the KIRs observed in these mice. -

Calreticulin—Multifunctional Chaperone in Immunogenic Cell Death: Potential Significance As a Prognostic Biomarker in Ovarian

cells Review Calreticulin—Multifunctional Chaperone in Immunogenic Cell Death: Potential Significance as a Prognostic Biomarker in Ovarian Cancer Patients Michal Kielbik *, Izabela Szulc-Kielbik and Magdalena Klink Institute of Medical Biology, Polish Academy of Sciences, 106 Lodowa Str., 93-232 Lodz, Poland; [email protected] (I.S.-K.); [email protected] (M.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-42-27-23-636 Abstract: Immunogenic cell death (ICD) is a type of death, which has the hallmarks of necroptosis and apoptosis, and is best characterized in malignant diseases. Chemotherapeutics, radiotherapy and photodynamic therapy induce intracellular stress response pathways in tumor cells, leading to a secretion of various factors belonging to a family of damage-associated molecular patterns molecules, capable of inducing the adaptive immune response. One of them is calreticulin (CRT), an endoplasmic reticulum-associated chaperone. Its presence on the surface of dying tumor cells serves as an “eat me” signal for antigen presenting cells (APC). Engulfment of tumor cells by APCs results in the presentation of tumor’s antigens to cytotoxic T-cells and production of cytokines/chemokines, which activate immune cells responsible for tumor cells killing. Thus, the development of ICD and the expression of CRT can help standard therapy to eradicate tumor cells. Here, we review the physiological functions of CRT and its involvement in the ICD appearance in malignant dis- ease. Moreover, we also focus on the ability of various anti-cancer drugs to induce expression of surface CRT on ovarian cancer cells. The second aim of this work is to discuss and summarize the prognostic/predictive value of CRT in ovarian cancer patients. -

Engrailed and Fgf8 Act Synergistically to Maintain the Boundary Between Diencephalon and Mesencephalon Scholpp, S., Lohs, C

5293 Erratum Engrailed and Fgf8 act synergistically to maintain the boundary between diencephalon and mesencephalon Scholpp, S., Lohs, C. and Brand, M. Development 130, 4881-4893. An error in this article was not corrected before going to press. Throughout the paper, efna4 should be read as EphA4, as the authors are referring to the gene encoding the ephrin A4 receptor (EphA4) and not to that encoding its ligand ephrin A4. We apologise to the authors and readers for this mistake. Research article 4881 Engrailed and Fgf8 act synergistically to maintain the boundary between diencephalon and mesencephalon Steffen Scholpp, Claudia Lohs and Michael Brand* Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG), Dresden, Germany Department of Genetics, University of Dresden (TU), Pfotenhauer Strasse 108, 01307 Dresden, Germany *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 23 June 2003 Development 130, 4881-4893 © 2003 The Company of Biologists Ltd doi:10.1242/dev.00683 Summary Specification of the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain However, a patch of midbrain tissue remains between the primordia occurs during gastrulation in response to signals forebrain and the hindbrain primordia in such embryos. that pattern the gastrula embryo. Following establishment This suggests that an additional factor maintains midbrain of the primordia, each brain part is thought to develop cell fate. We find that Fgf8 is a candidate for this signal, as largely independently from the others under the influence it is both necessary and sufficient to repress pax6.1 and of local organizing centers like the midbrain-hindbrain hence to shift the DMB anteriorly independently of the boundary (MHB, or isthmic) organizer. -

A Selective ER-Phagy Exerts Procollagen Quality Control Via a Calnexin-FAM134B Complex

Article A selective ER-phagy exerts procollagen quality control via a Calnexin-FAM134B complex Alison Forrester1,†, Chiara De Leonibus1,†, Paolo Grumati2,†, Elisa Fasana3,†, Marilina Piemontese1, Leopoldo Staiano1, Ilaria Fregno3,4, Andrea Raimondi5, Alessandro Marazza3,6, Gemma Bruno1, Maria Iavazzo1, Daniela Intartaglia1, Marta Seczynska2, Eelco van Anken7, Ivan Conte1, Maria Antonietta De Matteis1,8, Ivan Dikic2,9,* , Maurizio Molinari3,10,** & Carmine Settembre1,11,*** Abstract The EMBO Journal (2019) 38:e99847 Autophagy is a cytosolic quality control process that recognizes substrates through receptor-mediated mechanisms. Procollagens, Introduction the most abundant gene products in Metazoa, are synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and a fraction that fails to attain Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a homeostatic the native structure is cleared by autophagy. However, how auto- catabolic process devoted to the sequestration of cytoplasmic material phagy selectively recognizes misfolded procollagens in the ER in double-membrane vesicles (autophagic vesicles, AVs) that eventu- lumen is still unknown. We performed siRNA interference, CRISPR- ally fuse with lysosomes where cargo is degraded (Mizushima, 2011). Cas9 or knockout-mediated gene deletion of candidate autophagy Autophagy is essential to maintain tissue homeostasis and counter- and ER proteins in collagen producing cells. We found that the ER- acts both the onset and progression of many disease conditions, such resident lectin chaperone Calnexin (CANX) and the ER-phagy as ageing, neurodegeneration and cancer (Levine et al, 2015). receptor FAM134B are required for autophagy-mediated quality Substrates can be selectively delivered to AVs through receptor- control of endogenous procollagens. Mechanistically, CANX acts as mediated processes. Autophagy receptors harbour a LC3 or GABARAP co-receptor that recognizes ER luminal misfolded procollagens and interaction motif (LIR or GIM, respectively) that facilitate binding of interacts with the ER-phagy receptor FAM134B. -

On the Turning of Xenopus Retinal Axons Induced by Ephrin-A5

Development 130, 1635-1643 1635 © 2003 The Company of Biologists Ltd doi:10.1242/dev.00386 On the turning of Xenopus retinal axons induced by ephrin-A5 Christine Weinl1, Uwe Drescher2,*, Susanne Lang1, Friedrich Bonhoeffer1 and Jürgen Löschinger1 1Max-Planck-Institute for Developmental Biology, Spemannstrasse 35, 72076 Tübingen, Germany 2MRC Centre for Developmental Neurobiology, King’s College London, New Hunt’s House, Guy’s Hospital Campus, London SE1 1UL, UK *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 13 January 2003 SUMMARY The Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases and their turning or growth cone collapse when confronted with ligands, the ephrins, play important roles during ephrin-A5-Fc bound to beads. However, when added in development of the nervous system. Frequently they exert soluble form to the medium, ephrin-A5 induces growth their functions through a repellent mechanism, so that, for cone collapse, comparable to data from chick. example, an axon expressing an Eph receptor does not The analysis of growth cone behaviour in a gradient of invade a territory in which an ephrin is expressed. Eph soluble ephrin-A5 in the ‘turning assay’ revealed a receptor activation requires membrane-associated ligands. substratum-dependent reaction of Xenopus retinal axons. This feature discriminates ephrins from other molecules On fibronectin, we observed a repulsive response, with the sculpturing the nervous system such as netrins, slits and turning of growth cones away from higher concentrations class 3 semaphorins, which are secreted molecules. While of ephrin-A5. On laminin, retinal axons turned towards the ability of secreted molecules to guide axons, i.e. -

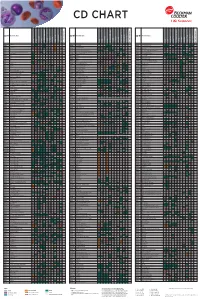

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

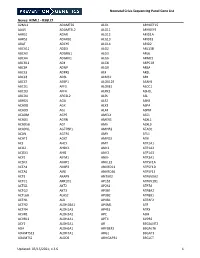

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Genetic, Cytogenetic and Physical Refinement of the Autosomal Recessive CMT Linked to 5Q31ð Q33: Exclusion of Candidate Genes I

European Journal of Human Genetics (1999) 7, 849–859 © 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 1018–4813/99 $15.00 t http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/ejhg ARTICLE Genetic, cytogenetic and physical refinement of the autosomal recessive CMT linked to 5q31–q33: exclusion of candidate genes including EGR1 Ang`ele Guilbot1, Nicole Ravis´e1, Ahmed Bouhouche6, Philippe Coullin4, Nazha Birouk6, Thierry Maisonobe3, Thierry Kuntzer7, Christophe Vial8, Djamel Grid5, Alexis Brice1,2 and Eric LeGuern1,2 1INSERM U289, 2F´ed´eration de Neurologie and 3Laboratoire de Neuropathologie R Escourolle, Hˆopital de la Salpˆetri`ere, Paris 4Laboratoire de cytog´en´etique, Villejuif 5G´en´ethon, Evry, France 6Service de Neurologie, Hˆopital des Sp´ecialit´es, Rabat, Morocco 7Service de Neurologie, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois, Lausanne, Switzerland 8Service D’EMG et de pathologie neuromusculaire, Hˆopital neurologique Pierre Wertheimer, Lyon, France Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease is an heterogeneous group of inherited peripheral motor and sensory neuropathies with several modes of inheritance: autosomal dominant, X-linked and autosomal recessive. By homozygosity mapping, we have identified, in the 5q23–q33 region, a third locus responsible for an autosomal recessive form of demyelinating CMT. Haplotype reconstruction and determination of the minimal region of homozygosity restricted the candidate region to a 4 cM interval. A physical map of the candidate region was established by screening YACs for microsatellites used for genetic analysis. Combined genetic, cytogenetic and physical mapping restricted the locus to a less than 2 Mb interval on chromosome 5q32. Seventeen consanguineous families with demyelinating ARCMT of various origins were screened for linkage to 5q31–q33. -

Methylome and Transcriptome Maps of Human Visceral and Subcutaneous

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Methylome and transcriptome maps of human visceral and subcutaneous adipocytes reveal Received: 9 April 2019 Accepted: 11 June 2019 key epigenetic diferences at Published: xx xx xxxx developmental genes Stephen T. Bradford1,2,3, Shalima S. Nair1,3, Aaron L. Statham1, Susan J. van Dijk2, Timothy J. Peters 1,3,4, Firoz Anwar 2, Hugh J. French 1, Julius Z. H. von Martels1, Brodie Sutclife2, Madhavi P. Maddugoda1, Michelle Peranec1, Hilal Varinli1,2,5, Rosanna Arnoldy1, Michael Buckley1,4, Jason P. Ross2, Elena Zotenko1,3, Jenny Z. Song1, Clare Stirzaker1,3, Denis C. Bauer2, Wenjia Qu1, Michael M. Swarbrick6, Helen L. Lutgers1,7, Reginald V. Lord8, Katherine Samaras9,10, Peter L. Molloy 2 & Susan J. Clark 1,3 Adipocytes support key metabolic and endocrine functions of adipose tissue. Lipid is stored in two major classes of depots, namely visceral adipose (VA) and subcutaneous adipose (SA) depots. Increased visceral adiposity is associated with adverse health outcomes, whereas the impact of SA tissue is relatively metabolically benign. The precise molecular features associated with the functional diferences between the adipose depots are still not well understood. Here, we characterised transcriptomes and methylomes of isolated adipocytes from matched SA and VA tissues of individuals with normal BMI to identify epigenetic diferences and their contribution to cell type and depot-specifc function. We found that DNA methylomes were notably distinct between diferent adipocyte depots and were associated with diferential gene expression within pathways fundamental to adipocyte function. Most striking diferential methylation was found at transcription factor and developmental genes. Our fndings highlight the importance of developmental origins in the function of diferent fat depots.