Integration of GBV Prevention Into Group Perinatal Care in Mali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

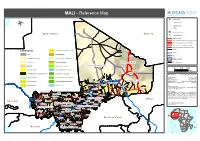

MALI - Reference Map

MALI - Reference Map !^ Capital of State !. Capital of region ® !( Capital of cercle ! Village o International airport M a u r ii t a n ii a A ll g e r ii a p Secondary airport Asphalted road Modern ground road, permanent practicability Vehicle track, permanent practicability Vehicle track, seasonal practicability Improved track, permanent practicability Tracks Landcover Open grassland with sparse shrubs Railway Cities Closed grassland Tesalit River (! Sandy desert and dunes Deciduous shrubland with sparse trees Region boundary Stony desert Deciduous woodland Region of Kidal State Boundary ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bare rock ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Mosaic Forest / Savanna ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Region of Tombouctou ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 0 100 200 Croplands (>50%) Swamp bushland and grassland !. Kidal Km Croplands with open woody vegetation Mosaic Forest / Croplands Map Doc Name: OCHA_RefMap_Draft_v9_111012 Irrigated croplands Submontane forest (900 -1500 m) Creation Date: 12 October 2011 Updated: -

9781464804335.Pdf

Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities Land Delivery Systems in West African Cities The Example of Bamako, Mali Alain Durand-Lasserve, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod A copublication of the Agence Française de Développement and the World Bank © 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / Th e World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 18 17 16 15 Th is work is a product of the staff of Th e World Bank with external contributions. Th e fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily refl ect the views of Th e World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent, or the Agence Française de Développement. Th e World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Th e boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of Th e World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of Th e World Bank, all of which are specifi cally reserved. Rights and Permissions Th is work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: Durand-Lasserve, Alain, Maÿlis Durand-Lasserve, and Harris Selod. -

District Sanitaire De Nara, Région De Koulikoro, Mali Avril, 2014

DISTRICT SANITAIRE DE NARA, RÉGION DE KOULIKORO, MALI AVRIL, 2014 BEATRIZ PÉREZ BERNABÉ 1 REMERCIEMENTS International Rescue Committee (IRC) et le Coverage Monitoring Network (CMN) adressent ses remerciements à toutes les personnes qui ont rendu possible la réalisation de cette évaluation de la couverture du programme PECIMA dans le district sanitaire de Nara de la région de Koulikoro. Aux autorités administratives et sanitaires de la Direction Régionale de la Santé (DRS) de Koulikoro et du District Sanitaire (DS) de Nara. Au personnel des CSCom et du CSRéf de Nara, et à toutes les personnes rencontrées dans les communautés – Agents de Santé Communautaires, relais, Groupes de Mères, autorités locales, leaders religieuses, guérisseurs et accoucheuses traditionnels, hommes et femmes; pour leur hospitalité, leur temps et coopération. Un remerciement très spécial à tous les enfants ainsi que leurs mères et autres accompagnants qui nous ont accueillis chaleureusement. Au personnel du bureau national d´IRC à Bamako, spécialement à Marie Biotteau, Anza Sahabi et le Dr Goita Ousmane pour avoir géré tous les préparatifs nécessaires pour le démarrage de l´investigation. A Dr Goita Ousmane et Fousseni Daniogo notamment pour ’leur engagement technique et logistique ainsi que dans la coordination des activités sur le terrain. Aussi à l’ONG CSPEEDA, pour son soutien logistique à l´investigation. Enfin, des remerciements particuliers aux officiers, médecins, infirmières et autre personnel d´IRC et de CSPEEDA qui ont participé dans l´investigation, pour -

Building a Decentralization Safo, Based on Socio-Cultural and Artistic Development of the Population ©2018 Konta 404

Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences Review Article Open Access Building a decentralization Safo, based on socio- cultural and artistic development of the population Abstract Volume 3 Issue 3 - 2018 The quest for new governance is underway in Mali since the national conference in 1992. It implies a redistribution of power in the management of resources and services for Mahamadou Konta communities. Above all, it requires a new behavior of the citizen, who must be mentally Head of Department Study and Research Program, Malian and intellectually prepared to become himself the main architect of his developmental Academy of Languages, Africa development of his locality. In the rural commune of Safo, where we have spent more than three years in need of investigation, the people and their elected officials are looking Correspondence: Mahamadou Konta, Head of Department Study and Research Program, Malian Academy of Languages, for an original way to achieve decentralization. The theme, “Building a decentralization Africa, Tel 7641 1270, Fax 6522 8889, Safo, based on socio-cultural and artistic development of the population” is an attempt Email [email protected] reconciliation of traditional and modern louse Also see around a common purpose, local development, based on the valuation redu socio-cultural heritage and artistic. Received: November 21, 2017 | Published: May 21 2018 Keywords: decentralization, socio-cultural, heritage, Safo, education, population Introduction Problem The socio cultural and artistic values can serve as inspiration to In the rural community of Safo, so development requirements revitalize education, governance and local development in the context necessary to the community, especially the customs and traditions of decentralization. -

Region De Koulikoro

Répartition par commune de la population résidente et des ménages Taux Nombre Nombre Nombre Population Population d'accroissement de de d’hommes en 2009 en 1998 annuel moyen ménages femmes (1998-2009) Cercle de Kati Tiele 2 838 9 220 9 476 18 696 14 871 2,1 Yelekebougou 1 071 3 525 3 732 7 257 10 368 -3,2 Cercle de Kolokani REGION DE KOULIKORO Kolokani 7 891 27 928 29 379 57 307 33 558 5,0 Didieni 4 965 17 073 17 842 34 915 25 421 2,9 En 2009, la région de Koulikoro compte 2 418 305 habitants répartis dans 366 811 ména- ème Guihoyo 2 278 8 041 8 646 16 687 14 917 1,0 ges, ce qui la place au 2 rang national. La population de Koulikoro est composée de Massantola 5 025 17 935 17 630 35 565 29 101 1,8 1 198 841 hommes et de 1 219 464 femmes, soit 98 hommes pour 100 femmes. Les fem- Nonkon 2 548 9 289 9 190 18 479 14 743 2,1 mes représentent 50,4% de la population contre 49,6% pour les hommes. Nossombougou 2 927 10 084 11 028 21 112 17 373 1,8 La population de Koulikoro a été multipliée par près de 1,5 depuis 1998, ce qui représente Ouolodo 1 462 4 935 5 032 9 967 9 328 0,6 un taux de croissance annuel moyen de 4%. Cette croissance est la plus importante jamais Sagabala 2 258 7 623 8 388 16 011 15 258 0,4 constatée depuis 1976. -

MINISTERE DE L'environnement REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ET DE L

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ET DE l’ASSAINISSEMENT UN PEUPLE/UN BUT/UNE FOI DIRECTION NATIONALE DES EAUX ET FORETS SYSTEME D’INFORMATION FORESTIER (SIFOR) SITUATION DES FOYERS DE FEUX DU 24 AU 26 JANVIER 2012 SELON LE SATTELITE MODIS Latitudes Longitudes Villages Communes Cercles Régions 11.5010000000 -8.4430000000 Bingo Tagandougou Yanfolila Sikasso 11.2350000000 -7.7150000000 Nianguela Kouroumini Bougouni Sikasso 10.3860000000 -8.0030000000 Ouroudji Gouandiaka Yanfolila Sikasso 13.5840000000 -10.3670000000 Oualia Oualia Bafoulabé Kayes 13.7530000000 -11.8310000000 Diangounte Sadiola Kayes 13.7500000000 -11.8160000000 12.8310000000 -9.1160000000 12.9870000000 -11.4000000000 Sakola Sitakily Kéniéba Kayes 12.9400000000 -11.1280000000 Gouluodji Baye Kéniéba 12.9370000000 -11.1100000000 12.9330000000 -11.1170000000 12.6190000000 -10.2700000000 Kouroukoto Kouroukoto Kéniéba Kayes 12.4730000000 -9.4420000000 Kamita Gadougou2 Kita Kayes 12.4690000000 -9.4490000000 12.1210000000 -8.4200000000 Ouoronina Bancoumana Kati Koulikoro 12.1090000000 -8.4270000000 12.3920000000 -10.4770000000 Madina Talibé Sagalo 12.4750000000 -11.0340000000 Koulia Faraba 12.4720000000 -11.0160000000 12.2010000000 -10.6680000000 Sagalo Sagalo 12.1980000000 -10.6480000000 Kéniéba Kayes 12.1990000000 -10.6550000000 12.4560000000 -10.9730000000 Koulia Faraba 12.4530000000 -11.0060000000 12.4670000000 -10.9820000000 13.2250000000 -10.2620000000 Manatali Bamafélé Bafoulabé Kayes 13.2340000000 -10.2350000000 Toumboubou Oualia 13.2300000000 -10.2710000000 -

The Mali Migration Crisis at a Glance

THE MALI MIGRATION CRISIS AT A GLANCE March 2013 The Mali Migration Crisis at a Glance International Organization for Migration TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents 2 Introduction 3 I Mali Migration Picture Prior to the 2012 Crisis 4 1. Important and Complex Circular Migration Flows including Pastoralist Movements 4 2. Migration Routes through Mali: from smuggling to trafficking of people and goods 4 3. Internal Migration Trends: Increased Urbanization and Food Insecurity 4 4. Foreign Population in Mali: Centered on regional migration 4 5. Malians Abroad: A significant diaspora 5 II Migration Crisis in Mali: From January 2012 to January 2013 6 1. Large Scale Internal Displacement to Southern Cities 6 2. Refugee Flows to Neighbouring Countries 6 3. Other Crisis-induced Mobility Patterns and Flows 7 III Mobility Patterns since the January 2013 International Military Intervention 8 1. Internal and Cross-Border Displacement since January 2013 8 2. Movements and Intention of Return of IDPs 8 IV Addressing the Mali Migration Crisis through a Holistic Approach 10 1. Strengthening information collection and management 10 2. Continuing responding to the most pressing humanitarian needs 10 3. Carefully supporting return, reintegration and stabilization 10 4. Integrating a cross-border and regional approach 10 5. Investing in building resilience and peace 10 References 12 page 2 Introduction INTRODUCTION variety of sources, including data collected through the Com- mission on Population Movement led by IOM and composed MIGRATION CRISIS of two national government entities, several UN agencies, and a number of NGOs. In terms of structure it looks at the Mali migration picture before January 2012 (Part I); the migration IOM uses the term “migration crisis” as a way to crisis as it evolved between January 2012 and the January refer to and analyse the often large-scale and 2013 international military intervention (Part II); and the situa- unpredictable migration flows and mobility tion since the military intervention (Part III). -

Download File

UNICEF MALI: COVID-19 Situation Report # 9 Reporting period 1st - 30 November 2020 Situation Overview and Humanitarian Needs Mali is facing the second wave of the COVID-19 epidemic since the last two weeks of November; over this period, cases have 4,688 COVID-19 been on a sharp rise impacting already overstretched health confirmed cases structures and depleting rapidly available stocks of supplies and equipment. 4,688 cases reported; 152 deaths (lethality of 3.2 per 3,178 recovered cent). The most affected region is Bamako (57.7 per cent of the total 152 deaths confirmed cases) followed by the regions of Timbuktu (12.4 per cent), Koulikoro (9.5 per cent) and Kayes (9.2 per cent) After a 2019-2020 school year disrupted by the COVID-19 epidemic and teacher’s strike, the new year will start on January 4, 2021. Some features Funding Situation 51 5,361 Funding Gap Health workers trained Sanitary corridors $4,421,888 on prevention and supported control of COVID-19 4,247 250 Funds available $22,618,037 Community Radios engaged Hand washing kits for sensitization on COVID-19 supplied to the MoH UNICEF’s COVID-19 Response and leaders) were trained in epidemiological surveillance and prevention of COVID-19. In Timbuktu, professionals of 6 Sanitary Cordons benefited training on COVID-19 and prevention materials to strengthen surveillance at borderlines. In terms of continuity of care, awareness raising on breastfeeding including in the context of COVID-19 continued in both facilities and community level, 37,558 caregivers of children (0-23 months) were reached with messages on breastfeeding. -

First Mali Report on the Implementation of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child

Republic of Mali One People – One Goal – One Faith FIRST MALI REPORT ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AFRICAN CHARTER ON THE RIGHTS AND WELFARE OF THE CHILD FOR THE 1999 – 2006 PERIOD Bamako, September 2007 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AN-RM National Assembly of the Republic of Mali. PTA Parents-Teachers Association ARV Anti- Retroviral ASACO Association de Santé Communautaire (Community Health Association) CAFO Coordination of Associations and Women NGOs of Mali CRC Convention on the Rights of the Child CED Centre d’Education pour le Développement (Education Centre for Development) CESC Economic, Social and Cultural Council CNAPN Comité National d’Action pour l’Eradication des Pratiques Néfastes à la santé de la Femme et de l’Enfant (National Action Committee for the Eradication of Harmful Practices on the Health of the Women and the Child) CNDIFE Centre National de Documentation et d’Information sur la Femme et l’Enfant. (National Documentation and Information Centre on the Woman and the Child) COMADE Coalition Malienne des Droits de l’Enfant (Malian Coalition for the Right of the Child) CPE Code for the Protection of the Child CSCOM Centre de Santé Communautaire (Community Health Centre) CSLP Poverty Alleviation Strategic Framework DNPF National Department of Women Empowerment. DNPEF National Department for the Promotion of the Child and the Family DNSI National Department of Statistics and Data Processing EDS III Population and Health Survey of Mali 2001 HCCT High Council of Territorial Councils IMAARV Malian Initiative for Access to Anti-Retrovirals -

Latitudes Longitudes Villages Communes Cercles Regions

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ET DE l’ASSAINISSEMENT UN PEUPLE/UN BUT/UNE FOI DIRECTION NATIONALE DES EAUX ET FORETS(DNEF) SYSTEME D’INFORMATION FORESTIER (SIFOR) SITUATION DES FOYERS DE FEUX DE BROUSSE DU 16 au 18 Mars 2013 SELON LE SATTELITE MODIS. LATITUDES LONGITUDES VILLAGES COMMUNES CERCLES REGIONS 15,1130000000 -4,3140000000 Farayeni Bimberetama Youwarou Mopti 13,1090000000 -7,2740000000 Oulla Tougouni Koulikoro Koulikoro 12,2220000000 -7,5260000000 Gouani Tiélé Kati Koulikoro 12,3130000000 -7,6640000000 Tamala Bougoula Kati Koulikoro 12,3270000000 -7,9290000000 Guelekoro Dialakoroba Kati Koulikoro 12,3840000000 -7,9280000000 Sirakoro Sanankoroba Kati Koulikoro 12,8600000000 -8,0000000000 Sikorobougou Kambila Kati Koulikoro 12,9050000000 -8,1370000000 Kababougou Kalifabougou Kati Koulikoro 13,2840000000 -8,4330000000 Djissoumal Daban Kati Koulikoro 13,7800000000 -8,1380000000 Bandiougou Kolokani Kolokani Koulikoro 14,4030000000 -6,1430000000 Hérébougou Sokolo Niono Ségou 12,4560000000 -8,4080000000 Fraguero Siby Kati Koulikoro 15,8220000000 -2,4580000000 Kelhantas Bambara Maoud G.Rharouss Tombouctou 11,9370000000 -8,5850000000 Mansaya Minidian Kangaba Koulikoro 14,1880000000 -7,5400000000 Kamissara Borron Banamba Koulikoro 12,8630000000 -6,6740000000 Niamana Wé Konobougou Baraoueli Ségou 11,9010000000 -6,4450000000 Kokoun Niantjila Dioila Koulikoro 12,1030000000 -7,8190000000 Kafara Ouéléssébougou Kati Koulikoro 12,1480000000 -7,0690000000 Douma Kemekako Dioila Koulikoro 14,0530000000 -4,5320000000 Kolloye Ouro -

Académie D'enseignement De KOULIKORO

MINISTERE DE L'EDUCATION NATIONALE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------------- Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi ------------------- SECRETARIAT GENERAL DECISION N° 20 13- / MEN- SG PORTANT ORIENTATION DES ELEVES TITULAIRES DU D.E.F, SESSION DE JUIN 2013, AU TITRE DE L'ANNEE SCOLAIRE 2013-2014. LE MINISTRE DE L'EDUCATION NATIONALE, Vu la Constitution ; Vu le Décret N°2013-721/P-RM du 8 septembre 2013 portant nomination des membres du Gouvernement ; Vu l'Arrêté N° 09 - 2491 / MEALN-SG du 10 septembre 2009 fixant les critères d’orientation, de transfert, de réorientation et de régularisation des titulaires du Diplôme d’Etudes Fondamentales (DEF) dans les Etablissements d’Enseignement Secondaire Général, Technique et Professionnel ; Vu la Décision N°10-2742/MEALN-SG-CPS du 04 juin 2010 déterminant la composition, les attributions et modalités de travail de la commission nationale et du comité régional d'orientation des élèves titulaires du diplôme d'études fondamentales (DEF), session de juin 2010 ; Vu la décision N°2011-03512 / MEALN–SG-IES du 19 Août 2011 fixant la Liste des Etablissements Privés d'Enseignement Secondaire éligibles pour accueillir des titulaires du Diplôme d'Etudes Fondamentales (DEF) pris en charge par l’Etat ; Vu la décision N° 2011-03614 / MEALN–SG-IES du 07 Septembre 2011 fixant la Liste additive des Etablissements Privés d'Enseignement Secondaire éligibles pour accueillir des titulaires du Diplôme d'Etudes Fondamentales (DEF) pris en charge par l’Etat ; Vu la décision N° 2011-03627 / MEALN–SG-IES du 09 Septembre 2011 fixant -

GE84/210 BR IFIC Nº 2747 Section Spéciale Special Section Sección

Section spéciale Index BR IFIC Nº 2747 Special Section GE84/210 Sección especial Indice International Frequency Information Circular (Terrestrial Services) ITU - Radiocommunication Bureau Circular Internacional de Información sobre Frecuencias (Servicios Terrenales) UIT - Oficina de Radiocomunicaciones Circulaire Internationale d'Information sur les Fréquences (Services de Terre) UIT - Bureau des Radiocommunications Date/Fecha : 25.06.2013 Expiry date for comments / Fecha limite para comentarios / Date limite pour les commentaires : 03.10.2013 Description of Columns / Descripción de columnas / Description des colonnes Intent Purpose of the notification Propósito de la notificación Objet de la notification 1a Assigned frequency Frecuencia asignada Fréquence assignée 4a Name of the location of Tx station Nombre del emplazamiento de estación Tx Nom de l'emplacement de la station Tx B Administration Administración Administration 4b Geographical area Zona geográfica Zone géographique 4c Geographical coordinates Coordenadas geográficas Coordonnées géographiques 6a Class of station Clase de estación Classe de station 1b Vision / sound frequency Frecuencia de portadora imagen/sonido Fréquence image / son 1ea Frequency stability Estabilidad de frecuencia Stabilité de fréquence 1e carrier frequency offset Desplazamiento de la portadora Décalage de la porteuse 7c System and colour system Sistema de transmisión / color Système et système de couleur 9d Polarization Polarización Polarisation 13c Remarks Observaciones Remarques 9 Directivity Directividad