The Real Heroine of Fairy Tales Donna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queering Kinship in 'The Maiden Who Seeks Her Brothers'

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2012 Queering Kinship in ‘The aideM n Who Seeks Her Brothers' Jeana Jorgensen Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jorgensen, Jeana, "Queering Kinship in ‘The aideM n Who Seeks Her Brothers'" Transgressive Tales: Queering the Brothers Grimm / (2012): 69-89. Available at http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers/698 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3 Queeting KinJtlip in ''Ttle Maiden Wtlo See~J Het BtottletJ_,_, JEANA JORGENSEN Fantasy is not the opposite of reality; it is what reality forecloses, and, as a result, it defines the limits of reality, constituting it as its constitutive outside. The critical promise of fantasy, when and where it exists, is to challenge the contingent limits of >vhat >vill and will not be called reality. Fa ntasy is what allows us to imagine ourselves and others otherwise; it establishes the possible in excess of the real; it points elsewhere, and when it is embodied, it brings the elsewhere home. -Judith Butler, Undoing Gender The fairy tales in the Kinder- und Hausmiirchen, or Children's and Household Tales, compiled by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are among the world's most popular, yet they have also provoked discussion and debate regarding their authenticity, violent imagery, and restrictive gender roles. -

Searching for Moral Lessons in "Rapunzel"

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2015 Vol. 13 Searching for Moral Lessons of “'the seven deadly sins of childhood'” (ix). He claims, “Every major fairy tale is unique in that it addresses a in “Rapunzel” specific failing or unhealthy predisposition in the self” Kara Nelson (Cashdan 13). He also believes in the rewards of teachers English 345 and parents “subtly” having children see a fairy tale's Summer 2014 “underlying sin” (Cashdan 15). In Cashdan's theory, the witch in these stories dies to “ensure that bad parts of the The Grimms' fairy tale “Rapunzel” does not self are eradicated and that good parts of the self prevail” portray the stereotypical evil stepmother, perfect prince, (35). Finally, Cashdan believes adult ties to fairy tales or immediate fairytale wedding. Hence, when adapted result from childhood experiences with them, since “it into various mediums, such as the movies Tangled and is in childhood that the seeds of virtue are sown” (20). Barbie as Rapunzel or the graphic novel Rapunzel's In order to understand certain complex tales such as Revenge, the story is often misinterpreted and reinvented “Rapunzel,” it is believed that a symbolic, historical, or since the world no longer values the tale's implied psychoanalytic analysis is not enough—these tales must morality and coming-of-age issues. While Bettelheim's also be viewed from a didactic or moral viewpoint. Freudian approach to fairy tales has been widely Indeed, “Rapunzel” addresses many moral criticized, he and many others, especially Sheldon issues. Zipes claims “Rapunzel” is not meant to be Cashdan, illustrate that fairy tales can hold deeper “didactic,” but that it has “the initiation of a virgin, who moral lessons. -

Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Puss in Boots

DECONSTRUCTION AND RECONSTRUCTION OF PUSS IN BOOTS AND HUMPTY DUMPTY CHARACTERS IN ANIMATED FILM PUSS IN BOOTS A Thesis Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Strata One By: ADE DWI SEPTIAN 1111026000077 ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT LETTERS AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2016 ABSTRACT Ade Dwi Septian, NIM. 1111026000077, Deconstruction and Reconstruction of Puss In Boots and Humpty Dumpty Characters in Animated Film Puss In Boots. Thesis: English Letters Department, Letters and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University of Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta, 2015. This thesis analyzes the animated film entitled Puss In Boots. The film is directed by Chris Miller was released in 2011. The problem in this film is located in the main characters, Puss In Boots and Humpty Alexandre Dumpty. The film is considered deconstructs the characteristics of the two main characters. In this case, Puss In Boots, fairy tale by Charles Perrault and Humpty Dumpty character in the novel Through The Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll are the benchmark. This research uses the deconstruction theory by Jacques Derrida. The method that is used in this research is descriptive qualitative. Puss In Boots is animated film that tells the story of the greatness of two buddies, Puss In Boots and Humpty Alexandre Dumpty, that become hero in a town called San Ricardo. However, the presence of Puss and Humpty as main characters in the film is contrary to the characteristics of Puss and Humpty in the fairy tale earlier. Generally, Puss and Humpty in this film shows a form of deconstruction related to the characteristics of Puss and Humpty in the fairy tale. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films Through Grotesque Aesthetics

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 9-10-2015 12:00 AM Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics Leah Persaud The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Angela Borchert The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Leah Persaud 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Persaud, Leah, "Who's the Fairest of Them All? Defining and Subverting the Female Beauty Ideal in Fairy Tale Narratives and Films through Grotesque Aesthetics" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3244. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3244 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? DEFINING AND SUBVERTING THE FEMALE BEAUTY IDEAL IN FAIRY TALE NARRATIVES AND FILMS THROUGH GROTESQUE AESTHETICS (Thesis format: Monograph) by Leah Persaud Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Leah Persaud 2015 Abstract This thesis seeks to explore the ways in which women and beauty are depicted in the fairy tales of Giambattista Basile, the Grimm Brothers, and 21st century fairy tale films. -

KIN S FUR.Indd

allerleirauh cinderella ALL KINDS OF FUR Erasure Poems & New Translation of a tale from the Brothers Grimm Margaret Yocom deerbrook editions published by Deerbrook Editions P.O. Box 542 Cumberland, ME 04021 www.deerbrookeditions.com first edition © 2018 by Margaret Yocom All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9991062-5-9 Author photograph by Jamie Lynn Photography. Cover art: Bear Girl by Anne Siems. www.annesiems.com Book Design by Jeffrey Haste. For John A note on the text: Poems in black font are erasures of the Author’s translation of Jakob and Wilhelm Grimms’ 1857 tale “Allerleirauh” (“All Kinds Of Fur”), a version of “Cinderella” that opens with incest. Contents Once there was a king 1 O golden hair and ashes 2 For a long time, the king could not 3 For a long time, I could not 4 Now the king had a daughter 5 daughter mother such golden hair 6 Then he spoke to his councillors 7 I a daughter a dead wife 8 The daughter was even more frightened 9 T he night herder’s maw 10 But she thought 11 turn 12 The king did not give up 13 his dun deer nears 14 Finally 15 all is red 16 In the night 17 go go 18 She walked the entire night 19 walk nigh hecate 20 Now it just so happened 21 so begin 22 When the hunters touched 23 touch 24 There 25 here 26 T hen 27 wood fire ashes 28 Now, one day 29 one so castled 30 to sweep up 31 the ashes tell 32 Everyone stepped aside 33 one step one 34 He thought in his heart 35 His eyes never behold 36 She, however 37 Swiftly Kind Fur 38 Now, when she came into the kitchen 39 Now, resume 40 And when the soup was ready -

Rapunzel Is Not Just a Princess in Fairy Tale

Rapunzel Is Not just a Princess in a Fairy Tale Column ideas sometimes arrive by chance, and from the strangest, offhand comments. Last week, my friend Terri said, “I want to ask you about an herb. I was reading nursery stories, and did you know that Rapunzel was named after an herb? Her mother ate so many of them while she was pregnant that she decided to name her baby daughter after the plant. The herbs were stolen from a witch’s garden, so she placed a curse on the baby.” It had been many years since I read “Rapunzel,” and I didn’t recall the reference to raiding the witch’s garden. I love researching odd stories and occurrences, and an unusual reference to the plant origin of the heroine’s name in a fairy tale piqued my interest. Terri is correct about the origin of Princess Rapunzel’s name. When the Brothers Grimm published “”Rapunzel” in 1812, rapunzel, or Campanula rapunculus, was commonly grown in herb and vegetable gardens. The plant name would have been familiar to readers of that period. Campanula rapunculus is a member of the Campanulaceae or bellflower family, of which there are 500 species. Campanula species are native to North Africa, Europe, and Western Asia. Other common names are bluebell and harebell. The Latin name “Campanula” translates as little bell and “rapunculus” is derived from the Latin word “rapa,” meaning small turnip, in reference to the parsnip or radish-like roots. An English-language common name of C. rapunculus is rampion, not to be confused with ramp or Allium tricoccum, a strongly flavored spring onion, native to the eastern United States and Canada, and the focus of spring festivals in Virginia, West Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. -

Working Title

Three Drops of Blood: Fairy Tales and Their Significance for Constructed Families Carol Ann Lefevre Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing Discipline of English School of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide South Australia June 2009 Contents 1. Abstract.……………………………………………………………iii 2. Statement of Originality…………………………………………..v 3. Introduction………………………………………………………...1 4. Identity and Maternal Blood in “The Goose Girl”………………9 5 “Cinderella”: The Parented Orphan and the ‘Motherline’….....19 6. Abandonment, Exploitation and the Unconscious Woman in “Sleeping Beauty”………………………………………….30 7. The Adoptive Mother and Maternal Gaze in “Little Snow White”………………………………………..44 8. “Rapunzel”: The Adoptee as Captive and Commodity………..56 9. Adoption and Difference in “The Ugly Duckling”……………..65 10. Conclusion……………………………………………………...…71 11. Appendix – The Child in the Red Coat: Notes on an Intuitive Writing Process………………………………....76 12. Bibliography................................................……………………...86 13. List of Images in the Text…..……………………………………89 ii Abstract In an outback town, Esther Hayes looks out of a schoolhouse window and sees three children struck by lightning; one of them is her son, Michael. Silenced by grief, Esther leaves her young daughter, Aurora, to fend for herself; against a backdrop of an absent father and maternal neglect, the child takes comfort wherever she can, but the fierce attachments she forms never seem to last until, as an adult, she travels to her father’s native Ireland. If You Were Mine employs elements of well-known fairy tales and explores themes of maternal abandonment and loss, as well as the consequences of adoption, in a narrative that laments the perilous nature of children’s lives. -

Fairytales in the German Tradition

German/LACS 233: Fairytales in the German Tradition Tuesday/Thursday 1:30-2:45 Seabury Hall S205 Julia Goesser Assaiante Seabury Hall 102 860-297-4221 Office Hours: Tuesday/Thursday 9-11, or by appointment Course description: Welcome! In this seminar we will be investigating fairytales, their popular mythos and their longevity across various cultural and historical spectrums. At the end of the semester you will have command over the origins of many popular fairytales and be able to discuss them critically in regard to their role in our society today. Our work this semester will be inter-disciplinary, with literary, sociological- historical, psychoanalytic, folklorist, structuralist and feminist approaches informing our encounter with fairytales. While we will focus primarily on the German fairytale tradition, in particular, the fairytales collected by the Brothers Grimm, we will also read fairytales from other cultural and historical contexts, including contemporary North America. Course requirements and grading: in order to receive a passing grade in this course you must have regular class attendance, regular and thoughtful class participation, and turn in all assignments on time. This is a seminar, not a lecture-course, which means that we will all be working together on the material. There will be a total of three unannounced (but open note) quizzes throughout the semester, one in-class midterm exam, two five-page essays and one eight-page final essay assignment. With these essays I hope to gauge your critical engagement with the material, as well as helping you hone your critical writing skills. Your final grade breaks down as follows: Quizzes 15% Midterm 15% 2- 5 page essays (15% each) 30% 1 8 page essay 20% Participation 20% House Rules: ~Class attendance is mandatory. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation. -

Fairy Tales Then and Now(Syllabus 2019)

Spring 2019 Professor Martha Helfer Office: AB 4125 Office hours, MW 1:30-2:30 p.m. and by appointment [email protected] Fairy Tales Then and Now MW5, 2:50-4:10 pm, AB 2225 01:470:225:01 (index 10423) 01: 470: 225: 02 (index 13663) 01:470:225:03 (index 18813) 01:470:225:04 (index 21452) 01: 470: H1 (index 13662) 01:195:246:01 (index 10485) 1 Course description: This course analyzes the structure, meaning, and function of fairy tales and their enduring influence on literature and popular culture. While we will concentrate on the German context, and in particular the works of the Brothers Grimm, we also will consider fairy tales drawn from a number of different national traditions and historical periods, including the American present. Various strategies for interpreting fairy tales will be examined, including methodologies derived from structuralism, folklore studies, gender studies, and psychoanalysis. We will explore pedagogical and political uses and abuses of fairy tales. We will investigate the evolution of specific tale types and trace their transformations in various media from oral storytelling through print to film, television, and the stage. Finally, we will consider potential strategies for the reinterpretation and rewriting of fairy tales. This course has no prerequisites. Core certification: Satisfies SAS Core Curriculum Requirements AHp, WCd Arts and Humanities Goal p: Student is able to analyze arts and/or literature in themselves and in relation to specific histories, values, languages, cultures, and/or technologies. Writing and Communication Goal d: Student is able to communicate effectively in modes appropriate to a discipline or area of inquiry. -

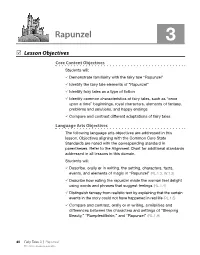

Rapunzelapunzel 3

RRapunzelapunzel 3 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Demonstrate familiarity with the fairy tale “Rapunzel” Identify the fairy tale elements of “Rapunzel” Identify fairy tales as a type of f ction Identify common characteristics of fairy tales, such as “once upon a time” beginnings, royal characters, elements of fantasy, problems and solutions, and happy endings Compare and contrast different adaptations of fairy tales Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Describe, orally or in writing, the setting, characters, facts, events, and elements of magic in “Rapunzel” (RL.1.3, W.1.3) Describe how eating the rapunzel made the woman feel delight using words and phrases that suggest feelings (RL.1.4) Distinguish fantasy from realistic text by explaining that the certain events in the story could not have happened in real life (RL.1.5) Compare and contrast, orally or in writing, similarities and differences between the characters and settings of “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rumplestiltskin,” and “Rapunzel” (RL.1.9) 40 Fairy Tales 3 | Rapunzel © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Compare and contrast, orally or in writing, similarities and differences between the read-alouds and a trade book for the story “Sleeping Beauty,” “Rumplestiltskin,” or “Rapunzel” (RL.1.9) Discuss personal responses to how they received their names and compare that to Rumpelstiltskin’s and Rapunzel’s names (W.1.8) Clarify information about “Rapunzel” by asking questions that begin with where (SL.1.1c) While listening to “Rapunzel,” orally predict what the man will do to save his wife and then compare the actual outcome to the prediction Core Vocabulary delight, n.