Mcollins DBA Dissertation FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

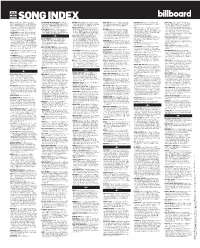

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

Spotlight on Erie

From the Editors The local voice for news, Contents: March 2, 2016 arts, and culture. Different ways of being human Editors-in-Chief: Brian Graham & Adam Welsh Managing Editor: Erie At Large 4 We have held the peculiar notion that a person or Katie Chriest society that is a little different from us, whoever we Contributing Editors: The educational costs of children in pov- Ben Speggen erty are, is somehow strange or bizarre, to be distrusted or Jim Wertz loathed. Think of the negative connotations of words Contributors: like alien or outlandish. And yet the monuments and Lisa Austin, Civitas cultures of each of our civilizations merely represent Mary Birdsong Just a Thought 7 different ways of being human. An extraterrestrial Rick Filippi Gregory Greenleaf-Knepp The upside of riding downtown visitor, looking at the differences among human beings John Lindvay and their societies, would find those differences trivial Brianna Lyle Bob Protzman compared to the similarities. – Carl Sagan, Cosmos Dan Schank William G. Sesler Harrisburg Happenings 7 Tommy Shannon n a presidential election year, what separates us Ryan Smith Only unity can save us from the ominous gets far more airtime than what connects us. The Ti Summer storm cloud of inaction hanging over this neighbors you chatted amicably with over the Matt Swanseger I Sara Toth Commonwealth. drone of lawnmowers put out a yard sign supporting Bryan Toy the candidate you loathe, and suddenly they’re the en- Nick Warren Senator Sean Wiley emy. You’re tempted to un-friend folks with opposing Cover Photo and Design: The Cold Realities of a Warming World 8 allegiances right and left on Facebook. -

A Novel & Exergesis

‘The White Distance’, a Novel And Reframing the Past for the Present: Writing ‘The White Distance’ By Susan Errington This Novel and Exegesis are submitted together in satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Creative Writing. Discipline of English, School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide October 2007 PhD Thesis- Susan Errington 1 Contents Part One 1. Acknowledgements 2. Declaration of Originality 3. Abstract Part Two: The Novel: ‘The White Distance’ 1. On the Red Field 2. Lovers 3. Parting 4. On The White Field 5. Revolutionaries 6. The Bomb-makers’ Party 7. Drummer 8. A Feather 9. Armistice Part Three: The Exegesis: Reframing the Past for the Present: Writing ‘The White Distance’ 1. Introduction: Writing ‘The White Distance’ 2. Inside The Ideas Factory: Eggs, Chickens and Pipe Bombs 3. Preposterous Histories: Cropping and Reframing the Past PhD Thesis- Susan Errington 2 4. Memoirs in the Museum: A Personal Reflection 5. The Tongue Set Free: Language and Memory in ‘The White Distance’ and Other Places 6. The White Indian: Why Use Kipling’s Poetry? 7. That Eye the Mind: Photographic and Other Visual Images in the Writing of ‘The White Distance’ 8. Another Country: How Should We Write About the Past? 9. The Real Inspector Vogelsang: A Contract with the Past? 10. In Conclusion: Reframing the Past for the Present Part Four 1. Bibliography 2. Appendix PhD Thesis- Susan Errington 3 Acknowledgements A great many fellow scholars and writers were very generous to me with assistance and encouragement in the writing of this Thesis. -

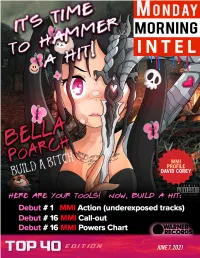

MMI PROFILE DAVID COREY JUNE 7, 2021 Tab Le O F Contents

MMI PROFILE DAVID COREY JUNE 7, 2021 Tab le o f Contents 4 #1 Songs THIS week 5 powers 6 action / recurrents 7 hotzone / developiong 8 pro-file 9 video streaming 11 Top 40 callout 12 future tracks 13 INTELESCOPE 14 intelevision 15 methodology 16 the back page Songs this week #1 BY MMI COMPOSITE CATEGORIES 6.7.21 ai r p lay JUSTIN BIEBER “Peaches f/Daniel Caesar/Giveon” retenTion DUA LIPA “Levitating” callout LIL NAS X “MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name)” audio OLIVIA RODRIGO “good 4 u” VIDEO BTS “Butter” SALES BTS “Butter” COMPOSITE DUA LIPA “Levitating” MondayMorningIntel.com CLICK HERE to E-MAIL Monday Morning Intel with your thoughts, suggestions, or ideas. mmi-powers 6.7.21 Weighted Airplay, Retention Scores, Streaming Scores, and Sales Scores this week combined and equally weighted deviser Powers Rankers. TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW RK TW COMP AIRPLAY RETENTION CALLOUT AUDIO VIDEO SALES RANK ARTIST TITLE LABEL 5 1 x 7 7 4 1 DUA LIPA Levitating Interscope-Warner 4 2 10 10 14 6 2 THE WEEKND Save Your Tears XO/Republic 9 6 11 8 4 3 3 MASKED WOLF Astronaut In The Ocean Elektra/EMG 21 x 19 1 2 2 4 OLIVIA RODRIGO good 4 u Geffen/Interscope 1 7 8 11 17 9 5 JUSTIN BIEBER Peaches f/Daniel Caesar/Giveon Def Jam 8 4 18 4 11 10 6 DOJA CAT Kiss Me More f/Sza Kemosabe/RCA 7 17 1 9 3 14 7 LIL NAS X MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name) Columbia 14 x 28 6 1 1 8 BTS Butter Columbia 3 8 4 15 21 16 9 THE KID LAROI Without You with Miley Cyrus Columbia 6 9 21 12 13 8 10 BRUNO MARS/A .PAAK/SILK SONIC Leave The Door Open Aftermath Ent./Atlantic 10 10 2 19 22 -

Youtube Charts

Youtube Top 100 Charts For May 12, 2021 TW LW Song Artist Weeks Views 26 22 Peaches Justin Bieber 7 3589742 1 51 Your Power Billie Eilish 2 8262948 27 In the morning ITZY 1 3512315 2 2 RAPSTAR Polo G 4 7594479 28 33 Outside MO3 & Og Bobby Billions 7 3437020 3 1 MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name) Lil Nas X 6 7130480 29 27 Streets Doja Cat 17 3436033 4 SORRY NOT SORRY DJ Khaled 1 6807026 30 29 First Day Out (Beat Box) NLE Choppa 5 3228511 5 6 Track Star Mooski 12 6115626 31 31 Hellcats & Trackhawks Only the Family & Lil Durk 9 3222937 6 5 Leave The Door Open Bruno Mars, Anderson .Paak & Silk Sonic 9 6036525 32 74 BIG PURR (Prrdd) (feat. Pooh Shiesty) Coi Leray 6 3168973 7 7 Back In Blood (feat. Lil Durk) Pooh Shiesty 26 5965224 33 25 deja vu Olivia Rodrigo 6 3165571 8 Final Warning NLE Choppa 1 5902722 34 32 Best Friend (feat. Doja Cat) Saweetie 16 3085580 9 4 On Me Lil Baby 22 5849669 35 28 Period (feat. DaBaby) Boosie Badazz 3 2972902 10 8 Calling My Phone Lil Tjay & 6LACK 12 5704679 36 24 If Pain Was A Person Moneybagg Yo 2 2933191 11 9 BeatBox 2 (feat. Pooh Shiesty) SpotemGottem 20 5345570 37 63 Wockesha Moneybagg Yo 2 2888930 12 14 Kiss Me More (feat. SZA) Doja Cat 4 5130894 38 34 DÁKITI Bad Bunny & Jhay Cortez 27 2846925 13 11 No More Parties (feat. Lil Durk) Coi Leray 14 4945698 39 36 Throat Baby (Go Baby) BRS Kash 35 2806002 14 3 Save Your Tears The Weeknd & Ariana Grande 18 4897168 40 Shit Crazy (feat. -

Removal Methods Questioned ESRP Expert Responds to the Handling Of

1.:;::::::::iiii Renegade Pantry I) The Renegade Rip 1-• J @the_renegade_rip Read SGA president member for mayor CJ @bc_rip candidate statements News, Page 5 www.therip.com Campus, Page 4 ene BAKERSFIELD COLLEGE Vol. 87 · No. 12 Wednesday, April 6, 2016 JOE BERGMAN / THE RIP The three light spots of dirt on the hillside in Memorial Stadium, shown in a March 17, 2016 photo, used to be kit-fox dens, and now they are go~e. _Th~ inset photo was given to The Rip by Brian Cypher of ESRP's Bakersfield program staff, and shows a kit fox with its pups in their natural habitat before work started on the h11ls1de m February of 2015. Removal ESRP expert responds to methods the handling of kit foxes By Mason J. Rockfellow propriate procedures and provided contact info for Editor in Chief agencies and individuals that could assist them." When destroying an endangered species' habitat questioned Regarding the issue of eradicating kit foxes or relocating tl1at species, tl1ere are a lot of vari from Bakersfield College's Memorial Stadium, an ables tl1at can stand in tl1e way. expert from the Environmental Species Recovery According to Cypher, the U.S. Fish and Wild By Joe Bergman Program said that ESRP was never contacted for life Service and California Department of Fish and Photo & Sports Editor advice or guidance on the matter. Wildlife states that to remove a den from an area, Brian L. Cypher, associate director and research The Renegade Rip has been investigating claims the den must be monitored to make sure that no kit ecologist, coordinates several of ESRP's research foxes are present. -

The Evolution of Masculinity and Mental Health Narratives in Rap Music

Man Down: The Evolution of Masculinity and Mental Health Narratives in Rap Music Rachel Hart,[1] Department of English, University of Bristol Abstract This article explores how one of the most typically hyper-masculine cultural arenas in Britain and America has evolved over the past 30 years, as rap artists decide to reject the stoicism of toxic masculinity in favour of promoting healthier conversations surrounding men’s mental health and associated coping mechanisms. Though rap has always been vocal about mental distress, its dominant narratives have evolved over the past 30 years to talk more specifically and positively about mental health issues. Over time rap has begun promoting therapy, medication, self-care and treatment, rather than self-medication via drugs and alcohol, or violence against the self or others. This is symbiotically informing and being informed by society’s changing ideas about masculinity and the construct of gender. In order to explore the evolution in discussions around men’s mental health from the 1990s to the present day, this article is split into three sections, each focusing on a different decade. I closely analyse the lyrics of one rap song in each chapter, which has been selected to represent rap’s general trends regarding discussions of mental health from that decade. I also briefly explore other songs that prove the decade’s trends. This article draws upon academic research as well as personal interviews undertaken with Solomon OB (2016’s National Poetry Slam champion), and Elias Williams, founder of MANDEM.com (an online media platform engaging with social issues and shining a light on young men of colour). -

2021 Song Index

FEB 13 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ANYONE (Bieber Time Publishing, ASCAP/Uni- BODY (1501 Certified Publishing, BMI/Hot Girl DAMAGE (Universal Music Corp., ASCAP/I Am EVIDENCE (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ GOODBYE (Copyright Control/Effective Records, Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By versal Music Corp., ASCAP/Song Goku, ASCAP/ Music, BMI/Sony/ATV Songs LLC, BMI/Songs Of H.E.R. Publishing, ASCAP/Heartfelt Productions Be Essential Songs, BMI/EGH Music Publishing PRS/Strengholt Music Group, BUMA/Peermusic RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music BMG Gold Songs, ASCAP/What Key Do You Universal, Inc., BMI/CD Baby, BMI/Tarik Brad- LLC, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/Anthony LLC, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI/We The (UK) Ltd, PRS/Method Paperwork, SESAC/Kobalt Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, Want It In Music, BMI/Songs With A Pure Tone, ford, BMI), HL, H100 20 ; RBH 8 ; RS 5 Clemons Jr. Publishing Designee, BMI/Tiara Kingdom Music, BMI), HL, CST 7 Group Music Publishing, SESAC/Spirit B-Unique ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp., BMI/ BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal Thomas Music, BMI/KMR II Music Royalties II Hits, BMI/Tileyard Music Publishing Ltd., BMI/ Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 43 BMG Platinum Songs US, BMI/R8D Music, BMI/ Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, SCSp, ASCAP/Kobalt Songs Music Publishing -F- Lighthouse Music Publishing, BMI/SHOUT! 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs Of BBMG, BMI/Kobalt Music Copyrights, ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 16 LLC, ASCAP), HL, H100 51 ; RBH 18 ; RBS 6 Music Publishing Australia, APRA/Universal STEMRA/Warner Chappell Music Holland B.V., SARL/1916 Publishing, ASCAP/BBMG Music, DAMN! (Ultra Music Publishing, SESAC/Jeris FACE TO FACE (NG Entertainment, BMI/Sony/ Music Publishing Pty. -

Two Weeks Ago Last Week This Week Certification RIAA Pos Peak. Weeks

4/12/2021 The Hot 100 Chart | Billboard Two Weeks Weeks Last this Certification Pos On Ago Week Week RIAA Peak. Chart #1 1 wks Montero (Call Me By Your Name) -- -- 1 Lil Nas X 1 1 Take A Daytrip, O.Fedi, R.Lenzo (M.L.Hill, D.M.A.Baptiste, D.Biral, O.Fedi, R.Lenzo) Columbia AG Peaches Justin Bieber Featuring Daniel Caesar & Giveon -- 1 2 0 2 HARV, Shndo (J.D.Bieber, A.Wotman, G.D.Evans, B.Harvey, L.M.Martinez Jr., L.B.Bell, F.King, M.S.Leon, K.Yazdani, A.Simmons) Raymond Braun Leave The Door Open Silk Sonic (Bruno Mars & Anderson .Paak) 2 3 3 0 4 Bruno Mars, D'Mile (Bruno Mars, B.Anderson, D.Emile II, C.B.Brown) Aftermath Up Cardi B 1 2 4 Yung Dza, DJ SwanQo, Sean Island (Cardi B, 0 8 J.K.Lanier Thorpe, J.D.Steed, E.Selmani, M.Allen, J.Baker) Atlantic Drivers License 3 4 5 Olivia Rodrigo 2 Platinum 0 12 D.Nigro (O.Rodrigo, D.L.Nigro) Geffen Save Your Tears The Weeknd 5 5 6 Platinum 0 16 Max Martin, O.T.Holter, The Weeknd (A.Tesfaye, A.Balshe, J.Quenneville, Max Martin, O.T.Holter) XO Levitating Dua Lipa Featuring DaBaby 7 7 7 Platinum 0 26 KOZ, S.D.Price (C.Coffee Jr., S.Kozmeniuk, S.T.Hudson, D.Lipa, J.L.Kirk, M.A.Elliott, M.Ciccone) Warner Blinding Lights The Weeknd 6 6 8 7 Platinum 0 69 Max Martin, O.T.Holter, The Weeknd (A.Tesfaye, A.Balshe, J.Quenneville, Max Martin, O.T.Holter) XO https://www.billboard.com/charts/Hot-100 2/12 4/12/2021 The Hot 100 Chart | Billboard Two Weeks Weeks Last this Certification Pos On Ago Week Week RIAA Peak. -

Lil Baby & Lil Durk's 'The Voice of the Heroes' Debuts at No. 1 On

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE JUNE 14, 2021 Page 1 of 18 INSIDE Lil Baby & Lil Durk’s ‘The Voice • BTS’ ‘Butter’ Sticks at No. 1 on Billboard of the Heroes’ Debuts at No. 1 on Hot 100, Bad Bunny’s ‘Yonaguni’ Debuts Billboard 200 Albums Chart at No. 10 BY KEITH CAULFIELD • CRB Sets Royalty Rate for Pandora, iHeartRadio and il Baby and Lil Durk’s collaborative al- 1) will be posted in full on Billboard’s website on June Other Webcasters bum, The Voice of the Heroes, debuts at No. 1 15. For all chart news, follow @billboard and @bill- on the chart, scoring the for- boardcharts on both Twitter and Instagram. • UK Festival Season Billboard 200 Thrown Into Doubt mer his second leader and the latter his first. Of Voice’s 150,000 equivalent album units earned in As Government LThe album bows with 150,000 equivalent album the tracking week ending June 10, SEA units comprise Extends Lockdown units earned in the U.S. in the week ending June 144,000 (equaling 197.71 million on-demand streams 10, according to MRC Data, driven nearly entirely of the album’s 18 tracks), album sales comprise • MusiCares Unveils Final, $2M Round by streaming activity of the its songs. The hip-hop slightly more than 4,000 and TEA units comprise a of COVID-19 set, which was released on June 4, also boasts guest little over 1,000. Relief Funding turns from a quartet of acts who have all had their Lil Durk is the sixth act to get their first No. -

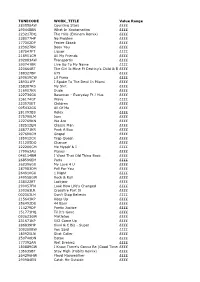

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 280558AW

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 280558AW Counting Stars ££££ 290448BN What In Xxxtarnation ££££ 223217DQ The Hills (Eminem Remix) ££££ 238077HP No Problem ££££ 177302DP Fester Skank ££££ 223627BR Been You ££££ 187547FT Liquor ££££ 218951CM All My Friends ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 290741BR Live Up To My Name ££££ 220664BT The Girl Is Mine Ft Destiny's Child & Brandy££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 258307KS My Shit ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 095432GS All Of Me ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 275790LM Ispy ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 297690CM Gospel ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 179963AU Planes ££££ 048114BM I Want That Old Thing Back ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 262396GU My Love 4 U ££££ 287983DM Fall For You ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 290057FN Look How Life's Changed ££££ 230363LR Crossfire Part Iii ££££ 002363LM Don't Stop Believin ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 256492DU 44 Bars ££££ 114279DP Poetic Justice ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 093623GW Mistletoe ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 180925LN Shot Caller ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 177392AN Wet Dreamz ££££ 180889GW I Know There's Gonna Be (Good Times)££££ 135635BT Stay High (Habits Remix) ££££ 264296HW Floyd Mayweather ££££ 290984EN Catch Me Outside ££££ 191076BP -

Youtube Hot 100 Charts

Youtube Top 100 Charts For June 9, 2021 TW LW Song Artist Weeks Views 26 30 Tombstone Rod Wave 11 3355910 1 1 Butter BTS 2 10360899 27 I DID IT DJ Khaled 1 3349214 2 2 good 4 u Olivia Rodrigo 3 9506669 28 29 Street Runner Rod Wave 13 3348052 3 22 Outside (Better Days) MO3 & Og Bobby Billions 11 7755921 29 34 Botella Tras Botella Gera Mx & Christian Nodal 6 3301359 4 3 MONTERO (Call Me By Your Name) Lil Nas X 10 6887713 30 32 Miss The Rage (feat. Playboi Carti)Trippie Redd 4 3283823 5 10 Save Your Tears The Weeknd 22 6597280 31 31 Heartbreak Anniversary Giveon 16 3207981 6 11 Leave The Door Open (Live) Bruno Mars, Anderson .Paak & Silk Sonic 13 6348814 32 28 Up Cardi B 17 3195257 7 8 Kiss Me More (feat. SZA) Doja Cat 8 5861417 33 26 drivers license Olivia Rodrigo 21 3074275 8 5 Wockesha Moneybagg Yo 6 5771816 34 7 GANG GANG Polo G & Lil Wayne 2 2980690 9 6 RAPSTAR Polo G 8 5464129 35 Tell Em Cochise & $NOT 1 2968224 10 Lucid Dreams Juice WRLD 48 5436290 36 24 traitor Olivia Rodrigo 2 2914155 11 9 Astronaut In The Ocean Masked Wolf 18 5174484 37 33 On Me Lil Baby 26 2810064 12 12 Back In Blood (feat. Lil Durk) Pooh Shiesty 30 4950902 38 40 Dick (feat. Doja Cat) StarBoi3 5 2749388 13 4 Build a Bitch Bella Poarch 3 4922874 39 39 Peaches (feat. Daniel Caesar & Giveon) Justin Bieber 11 2743087 14 14 EVERY CHANCE I GET DJ Khaled 5 4870060 40 35 Straightenin Migos 3 2659097 15 13 Calling My Phone Lil Tjay & 6LACK 16 4849000 41 37 Big Gangsta Kevin Gates 24 2602558 16 Lost Cause Billie Eilish 1 4763947 42 42 Best Friend (feat.