Robert Hodgins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official E-Programme

OFFICIAL E-PROGRAMME Versus Castleford Tigers | 16 August 2020 Kick-off 4.15pm 5000 BETFRED WHERE YOU SEE AN CONTENTS ARROW - CLICK ME! 04 06 12 View from the Club Roby on his 500th appearance Top News 15 24 40 Opposition Heritage Squads SUPER LEAGUE HONOURS: PRE–SUPER LEAGUE HONOURS: Editor: Jamie Allen Super League Winners: 1996, 1999, Championship: 1931–32, 1952–53, Contributors: Alex Service, Bill Bates, 2000, 2002, 2006, 2014, 2019 1958–59, 1965–66, 1969–70, 1970–71, Steve Manning, Liam Platt, Gary World Club Challenge Honours: 1974–75 Wilton, Adam Cotham, Mark Onion, St. Helens R.F.C. Ltd 2001, 2007 Challenge Cup: 1955–56, 1960–61, Conor Cockroft. Totally Wicked Stadium, Challenge Cup Honours: 1996, 1997, 1965–66, 1971–72, 1975–76 McManus Drive, 2001, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2008 Leaders’ Shield: 1964–65, 1965–66 Photography: Bernard Platt, Liam St Helens, WA9 3AL BBC Sports Team Of The Year: 2006 Regal Trophy: 1987–88 Platt, SW Pix. League Leaders’ Shield: 2005, 2006, Premiership: 1975–76, 1976–77, Tel: 01744 455 050 2007, 2008, 2014, 2018, 2019 1984–85, 1992–93 Fax: 01744 455 055 Lancashire Cup: 1926–27, 1953–54, Ticket Hotline: 01744 455 052 1960–61, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, Email: [email protected] 1964–65, 1967–68, 1968–69, 1984–85, Web: www.saintsrlfc.com 1991–92 Lancashire League: 1929–30, Founded 1873 1931–32, 1952–53, 1959–60, 1963–64, 1964–65, 1965–66, 1966–67, 1968–69 Charity Shield: 1992–93 BBC2 Floodlit Trophy: 1971–72, 1975–76 3 VIEW FROM THE CLUB.. -

Heartstone: the Parish of Sacred Heart & St John Stone, Ainsdale

We are living the Next Chapter of Christianity on Planet Earth: Week #49 Glorifying God by our Lives. HeartStone: the parish of Sacred Heart & St John Stone, Ainsdale Living the Love of Christ: everyone welcome, everyone matters, everyone involved. Sunday 8th August – 19th Sunday of Ordinary Time Church & Spirituality Virtual Church & Community Service & Community 5.30 MassSat: People of Parish SJS Bernie & John Cornett (50th Wed anniv) Gerry Lovelady (A) 6.30 Holy Communion outside SH Sun 10.30 Mass: Eileen Moore (A) SJS 10.30am Mass Zoomed from church Maureen Fletcher (LD) Mon 9.30am Morning Prayer in Church daily SJS Tue Wed 11-12.00 Private Prayer in church Fr Tony Returns 12.00 Mass: Teresa Slingo (ILM) SJS 11-12 Place2Be SJS Hall 4.30 Impact Extra zoom 9pm “The Elderleys” SJS Club Thu Fr Tony: Hospital Ministry 1-3pm Ainsdale Foodbank Fri NO Mass Today Sat 10am Living Christ Breakfast zoom Sunday 15th August – Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Sat 5.30 Mass: Trainor Family SJS 6.30 Holy Communion outside SH Sun 10.30am Mass Zoomed from church 10.30 Mass: People of Parish, Andrew Maher (ILM) SJS WE JOIN IN PRAYER TOGETHER We give thanks to Fr Richard Sloan and Fr John Bradley for their beautify ministry whilst Fr Tony has been away. Support for all struggling, the unemployed. Find signposts for help at: heartstonerc.co.uk/“Wellbeing & Support” All who are sick: Jo Cassidy, Izzy (13), Isabella Walker, Pat Kelly, Peter, Pat Naylor and the housebound. Please inform of those needing prayers, or who have recovered For all who have died recently: Maureen Fletcher, and those whose anniversaries occur at this time: Graham Mackey, Michael Dowd, Eileen Moore, Gerry Lovelady For prayers for your intentions email [email protected]. -

Arthur Atkinson

Arthur Atkinson Arthur Atkinson was born on April 5,1906 at 12 Alfred Street, Castleford, just off Wheldon Road, where the now demolished Nestle's factory used to be. The 1911 Census however shows the family residing in Radcliffe, Lancashire and Arthur, then aged 5, at school there. Fortunately for Castleford fans however Arthur, at least, returned to Castleford. Legend has it that Arthur was behind the posts one day at Castleford's old ground at Sandy Desert, Lock Lane, when he fielded the ball and with expert ease punted or drop-kicked it back into the field of play and that a certain Mr Walter Smith saw a potential star in the making. Arthur signed for the club in 1926 as they made their introduction into the Rugby Football League and made his debut for the first team in their fifth match, away at Rochdale, on Saturday 11 September, 1926 when they lost 33-5. Arthur quickly made his mark in the side and scored his first try against Halifax the following month although Cas were destined to finish bottom of the league in their first season. Displaying strong qualities of leadership at an early age, he was appointed captain in the 1928-29 season, a role he retained until his retirement in 1942. His form that season alerted selectors to his abilities and he made his debut for Yorkshire, becoming the first Castleford player to gain such an honour, in the game against Glamorgan and Monmouth at Cardiff, going on to earn 14 caps for his county and became Castleford's first full international in that same season, eventually playing six times for England and ten times for Great Britain, including two tours to Australasia, for whom he scored five tries, and there were clear signs of what was to come as the team reached the semi final of the Challenge Cup, the first year that the final was to be played at Wembley. -

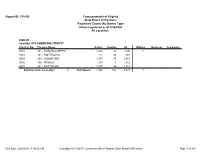

Registrant Counts by District Type Commonwealth of Virginia State

Report ID: CP-150 Commonwealth of Virginia State Board of Elections Registrant Counts By District Type Voters registered as of 2/26/2008 All Localities CON 01 Locality: 033 CAROLINE COUNTY Precinct No. Precinct Name Active Inactive All Military Overseas Temporary 0101 101 - BOWLING GREEN 2,843 52 2,895 1 0301 301 - PORT ROYAL 777 24 801 0303 303 - WOODFORD 1,377 37 1,414 0402 402 - PENOLA 234 8 242 0501 501 - MATTAPONI 2,677 44 2,721 # of Precincts in Locality: 5 # of Voters: 7,908 165 8,073 1 Run Date: 2/26/2008 11:04:22 AM Copyright 01/01/2007, Commonwealth of Virginia, State Board of Elections Page 1 of 193 Report ID: CP-150 Commonwealth of Virginia State Board of Elections Registrant Counts By District Type Voters registered as of 2/26/2008 All Localities CON 01 Locality: 057 ESSEX COUNTY Precinct No. Precinct Name Active Inactive All Military Overseas Temporary 0101 101 - GREATER TAPPAHANNOCK 1,492 38 1,530 0201 201 - NORTH 1,595 43 1,638 0301 301 - SOUTH 1,496 39 1,535 0401 401 - CENTRAL 1,745 33 1,778 # of Precincts in Locality: 4 # of Voters: 6,328 153 6,481 Run Date: 2/26/2008 11:04:22 AM Copyright 01/01/2007, Commonwealth of Virginia, State Board of Elections Page 2 of 193 Report ID: CP-150 Commonwealth of Virginia State Board of Elections Registrant Counts By District Type Voters registered as of 2/26/2008 All Localities CON 01 Locality: 061 FAUQUIER COUNTY Precinct No. -

2021 Inspector Assignments List

ID Establishment Name Address EHS Assigned Phone Number E-Mail Address 500000 100 NORMAN PLACE 16521 BARCICA LANE Miller, Natalie (704) 371-1575 [email protected] 501495 1100 SOUTH 1100 SOUTH BLVD Dutcher, Tim (980) 314-1631 [email protected] 560027 1100 SOUTH - SPRAYPAD 1100 SOUTH BLVD Hall, Matt (704) 575-3541 [email protected] 501237 230 SOUTH TRYON COA 230 S TRYON ST Sturgess, Willie (980) 445-8725 [email protected] 500926 49 NORTH 10035 DABNEY DRIVE Shelton, Braedon (980) 297-3719 [email protected] 501364 5115 PARK PLACE 5115 PARK RD Thompson, Cassandra (704) 574-6122 [email protected] 500287 6300 WOODBEND LLC 6320 WOODBEND DR Yow, Kaitlyn (704) 330-9475 [email protected] 501010 715 N CHURCH STREET COA 715 N CHURCH ST Michaud, Ryan (704) 621-6251 [email protected] 500005 800 CHEROKEE ASSOCIATION 900 CHEROKEE ROAD Sturgess, Willie (980) 445-8725 [email protected] 500909 901 PLACE 901 FORTY NINER AVENUE Shelton, Braedon (980) 297-3719 [email protected] 500590 A, A. NOOR ENTERPRISE,LLC 2101 OAK LEIGH DRIVE Dutcher, Tim (980) 314-1631 [email protected] 501404 ABBEY, THE 1415 ABBEY PLACE Thompson, Cassandra (704) 574-6122 [email protected] 500922 ADAIR AT BALLANTYNE 14586 ADAIR MANOR COURT McIntosh, Hope (980) 229-7549 [email protected] 500808 ADDISON PARK APARTMENTS 6225 HACKBERRY CREEK TRAIL Presley, Jacob (980) 314-1646 [email protected] 500834 ADDISON PARK APARTMENTS-2 6455 HACKBERRY CREEK TRAIL Presley, Jacob (980) 314-1646 -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

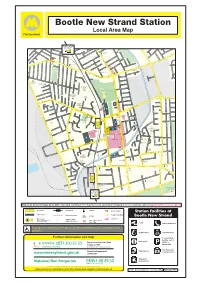

Bootle New Strand Station Local Area Map

Bootle New Strand Station Local Area Map Trains towards Southport PriorP Street et rio reee M d r S StrSt oa tree k ono R KiplingK Street t t d e i occk a n al p e f d li d oao S a s ng e idddo StSt Andrews R in r PopePo Street R t R efte R A S t pe t e ChurchChurch n t BowlesB Street tr S H re f o t e t o t e o e S r w e eet S t o a e e o r t a h n d l y r t e e rrn h LiL L g s t n p u R S u a l i R S t u rayr Stree A r n t S bby h AuA oao e e re y n a G e v e e t w t d E l r E B d r u A a l RRo e o a l e lli o o o an BulwerB Streetl l R n L i d a o u a e o o a lle ooa S m R d r d e o d ac MooreM Street t p Str t R tant h n e Knowsley Ro v y a tth R Li ad S a a e a mma n L d o t D rrd lldd lel a a r d i e oao eet e R d MiM y d e TheThe R oror t f QQueensueens BankhallBankhall d o uf d MissionMission a M a RufR ad oa Roado d oado lt RoR a R AlA V CChurchhurch th r R e t a tethe R kfk ia xxt u t f t ro iei d e e ydiay x e t CroC L t t l e t e e d C e r e r e e t R e t n e R e a r r e L TheThe r S r e La e t S r r o treett t accr t l n Linacree s r S a iin l t S L S c S d e e e t n ene s y p e e n w e n reetr n a e t H o w y r s r a d t r W r r t e t o S u o y m a GrayG Street y m r e S u w BoswellB Street CowperC Street S BurnsB S e K B e t n DrydenD Street r o ttho n r w e h t o s o l e e o t L o S y d r R ly Street r o July StreetS r t ad i a T tht nne MooreM St y o h S o h c e N ere r t P o e R e t R r l e R Norton Street rnr o r l a o n a ooa d PercyP Street c u t n a o o SScott Stree d d f H n l StSt JoanJoan ofof Arc o R a r R StSt -

St. Oswald and Netherton and Orrell Area Committee

THE “CALL IN” PERIOD FOR THIS SET OF MINUTES ENDS AT 12 NOON ON THURSDAY, 15TH APRIL, 2004. MINUTE NOS. 81, 83, 84, 85, 86 AND 87 ARE NOT SUBJECT TO “CALL IN” ST. OSWALD AND NETHERTON AND ORRELL AREA COMMITTEE Meeting held at the Netherton Park Primary School, Netherton on 18th March, 2004 Present:- Councillor Mahon (in the Chair); Councillors Brennan, P. Dowd and Martin. Local Advisory Group Member - Ms. M. Elson. Plus 30 members of the public and a member of Merseyside Police. (An apology for absence was received from Councillor Maher). 78. MINUTES The Minutes of the meeting held on 19th February, 2004 were approved. 79. COUNCILLOR BILL BURKE The Chair referred, with great regret, to the recent death of Councillor Bill Burke, a Member of the Council since 1978 and a member of this Committee since its inception. Those present then stood in silence as a mark of respect to his memory. 80. PROPOSED NEW IKEA STORE - DUNNINGS BRIDGE ROAD, NETHERTON Representatives of Ikea outlined plans by that company for a new store on a site adjacent to Dunnings Bridge Road, Netherton. The representatives answered questions from members of the public. In addition, Mr. Jeff Gibbons, the Planning and Economic Regeneration Director, indicated that he would be arranging local “surgeries” where members of his staff would be available to answer detailed questions from members of the public on the company’s planning application. 61 ST. OSWALD AND NETHERTON AND ORRELL AREA COMMITTEE - 18/3/2004 RESOLVED :- That the representatives of Ikea be thanked for their presentation. -

Founded on Coal

FOUNDED ON COAL A HISTORY OF A COAL MINING COMMUNITY: THE PARISH OF ST. MATTHEW HIGHFIELD AND WINSTANLEY by RAY WINSTANLEY and DEREK WINSTANLEY with a foreword bv Rev. W. Bynon Copyright R. & D. Winstanley, 1981 Published by R. Winstanley, 22 Beech Walk, Winstanley. Printed by the Supplies Section of the Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council (Administration Department) FOREWORD When walking or driving along Pemberton Road and Billinge Road, you are aware of the new housing estates and the rush of traffic. It is not difficult to imagine that the Parish of Highfield is one of the new suburbs created to absorb the workers of Lancashire and Merseyside. The truth is very different as you will discover in the pages of this book. The history of this area can be traced back to the Domesday Book of 1086 A. D. and by far the most historic building is Winstanley Hall. As a legal parish we can only go back to 1910, but as a church we go back to 1867 when the Pemberton Colliery Church School was built. The name of Pemberton Colliery gives us a clue to the origin of a church on this site. The link between the Blundell family and the Church has given to this parish the schools, the cricket Field, the graveyard and the vicarage. The present church, completed in 1894, was the gift of Col. Blundell in memory of his wife, Lady Blundell. The Blundell family were generous benefactors to the parish. Although the physical area referred to in this book is that of the parish of St Matthew, this is the history not just of a church, but of a whole community. -

Digest of Tourism Statistics Updated December 2013

Digest of Tourism Statistics Updated December 2013 Digest of Tourism Statistics North West Research Liverpool LEP December 2013 Page 1 £10 FREE to Members Contents Introduction 3 The Key Facts 4 1 Overall Size of the Visitor Economy (STEAM) 5 1.1 Number of visitors (volume) 5 1.2 Total spend by visitors (value) 6 1.3 Jobs supported by the visitor economy 7 1.4 Change over time 9 1.5 STEAM Methodology 10 2 Local data from the Visitor Economy 11 2.1 Hotel occupancy 11 2.2 Hotel stock 14 2.3 Visits to attractions 15 2.4 Sport 16 2.5 Events 17 2.6 Transport data 18 3 Visitor profile data 23 3.1 Visitor Origin 23 3.2 Mode of transport 27 3.3 Purpose of visit 28 3.4 Demographics 29 3.5 Group type 31 4 National data 32 4.1 Occupancy trends 32 4.2 Visits to attractions trends 33 4.3 Domestic visitors (GBTS) 34 4.4 Inbound visitors (IPS) 36 5 Forecasts 38 5.1 Trends from the Liverpool City Region 3-year Action Plan 38 6 Articles 39 6.1 Business Performance 39 6.2 Tourism Business Confidence - Nationally 44 6.3 News 46 Appendices 48 Further reference sources 48 SIC codes defining the visitor economy 49 Crude guide to statistical confidence levels 50 Details of available publications 51 Digest of Tourism Statistics North West Research Liverpool LEP December 2013 Page 2 FREE to Members Introduction Welcome to the latest edition of the Digest of Tourism Statistics. The Digest collates a range of key tourism research sets for the Liverpool City Region and is intended for all users of tourism data; whether businesses, consultants or students. -

Sefton Council Election Results 1973-2012

Sefton Council Election Results 1973-2012 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Rugby League As a Televised Product in the United States of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications, College Journalism and Mass Communications of 7-31-2020 Rugby League as a Televised Product in the United States of America Mike Morris University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Morris, Mike, "Rugby League as a Televised Product in the United States of America" (2020). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Rugby League as a Televised Product in the United States of America By Mike Morris Abstract Rugby league is a form of rugby that is more similar to American football than its more globally popular cousin rugby union. This similarity to the United States of America’s most popular sport, that country’s appetite for sport, and its previous acceptance of foreign sports products makes rugby league an attractive product for American media outlets to present and promote. Rugby league’s history as a working-class sport in England and Australia will appeal to American consumers hungry for grit and authenticity from their favorite athletes and teams.