Linguistic Diversity in the Fifteenth-Century Stonor Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

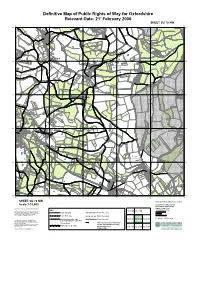

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21St February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 78 NW

Definitive Map of Public Rights of Way for Oxfordshire Relevant Date: 21st February 2006 Colour SHEET SU 78 NW 70 71 72 73 74 75 B 480 1200 7900 B 480 8200 0005 Highclere B 480 7300 The Well The B 480 Croft Crown Inn The Old School House Unity Cottage 322/25 90 Pishilbury 90 377/30 Cottage Hall 322/21 Well 322/20 Pool Walnut Tree Cottage 3 THE OLD ROAD 2/2 32 Bank Farm Walnut Tree Cottage 8086 CHURCH HILL The Beehive Balhams' Farmhouse Pishill Church 9683 LANE 2/22 6284 Well Pond Hall Kiln BALHAM'S Barn 32 PISHILL Kiln Pond 322/22 6579 Cottages 0076 322/22 HOLLANDRIDGE LANE Upper Nuttalls Farm 322/16 Chapel Wells Pond 0076 Thatchers Pishill House 0974 322/15 5273 Green Patch 322/25 Rose Cottage Pond B 480 The Orchard B 480 7767 Horseshoe Cottage Strathmore The 322/17 37 Old Chapel Lincolns Thatch Cottage Ramblers Hey The White House 7/ Goddards Cottage 322/22 The Old Farm House 30 April Cottage The Cottage Softs Corner Tithe Barn Law Lane 377/30 Whitfield Flint Cottage Commonside Cedarcroft BALHAM'S LANE 322/20 322/ Brackenhurst Beech Barn 0054 0054 27 322/23 6751 Well 322/10 Whistling Cottage 0048 5046 Morigay Nuttall's Farm Tower Marymead Russell's Water 2839 Farm 377/14 Whitepond Farm 322/9 0003 377/15 7534 0034 Pond 0034 Redpitts Lane Little Balhams Pond Elm Tree Hollow Snowball Hill 1429 Ponds Stonor House Well and remains of 0024 3823 Pond 2420 Drain RC Chapel Pond (Private) 5718 Pond Pond Pond 322/20 Redpitts Farm 9017 0513 Pond Pavilion Lodge Lodge 0034 The Bungalow 1706 0305 9 4505 Periwinkle 7/1 Cottage 0006 Well 322/10 0003 -

Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxford Archdeacons’ Marriage Bond Extracts 1 1634 - 1849 Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1634 Allibone, John Overworton Wheeler, Sarah Overworton 1634 Allowaie,Thomas Mapledurham Holmes, Alice Mapledurham 1634 Barber, John Worcester Weston, Anne Cornwell 1634 Bates, Thomas Monken Hadley, Herts Marten, Anne Witney 1634 Bayleyes, William Kidlington Hutt, Grace Kidlington 1634 Bickerstaffe, Richard Little Rollright Rainbowe, Anne Little Rollright 1634 Bland, William Oxford Simpson, Bridget Oxford 1634 Broome, Thomas Bicester Hawkins, Phillis Bicester 1634 Carter, John Oxford Walter, Margaret Oxford 1634 Chettway, Richard Broughton Gibbons, Alice Broughton 1634 Colliar, John Wootton Benn, Elizabeth Woodstock 1634 Coxe, Luke Chalgrove Winchester, Katherine Stadley 1634 Cooper, William Witney Bayly, Anne Wilcote 1634 Cox, John Goring Gaunte, Anne Weston 1634 Cunningham, William Abbingdon, Berks Blake, Joane Oxford 1634 Curtis, John Reading, Berks Bonner, Elizabeth Oxford 1634 Day, Edward Headington Pymm, Agnes Heddington 1634 Dennatt, Thomas Middleton Stoney Holloway, Susan Eynsham 1634 Dudley, Vincent Whately Ward, Anne Forest Hill 1634 Eaton, William Heythrop Rymmel, Mary Heythrop 1634 Eynde, Richard Headington French, Joane Cowley 1634 Farmer, John Coggs Townsend, Joane Coggs 1634 Fox, Henry Westcot Barton Townsend, Ursula Upper Tise, Warc 1634 Freeman, Wm Spellsbury Harris, Mary Long Hanburowe 1634 Goldsmith, John Middle Barton Izzley, Anne Westcot Barton 1634 Goodall, Richard Kencott Taylor, Alice Kencott 1634 Greenville, Francis Inner -

Cllrs Freddie Van Mierlo, Liz Leffman and David Turner at Martin-Baker, Chalgrove

Photo - Cllrs Freddie van Mierlo, Liz Leffman and David Turner at Martin-Baker, Chalgrove Focus on Parishes with Cllr Freddie van Mierlo (Chalgrove and Watlington) August 2021 Welcome to my monthly update. I will be sharing a regular update in the first week of every month. In the interests of transparency and sharing good ideas I will be sharing this update publicly as well as with parish councils in Chalgrove and Watlington division. It has been a very busy month with lots of progress on all fronts! See below for more details! My recent meetings • 5th July: Britwell Salome Parish Council • 6th July: Nettlebed Parish Council • 8th July: Berrick Salome Parish Council • 12th July: Swyncombe Parish Council • 13th July: Full County Council Meeting • 13th July: Pyrton Parish Council • 13th July: Watlington Parish Council • 14th July: Little Milton Parish Council • 3rd August: Pishill with Stonor Parish Council • 5th August: Martin-Baker Aircraft Company (Chalgrove airfield) • 6th August: Resident of Watlington on issue of special educational needs Upcoming meetings: • 12th August: Britwell Salome Parish Council If there are meetings you would like to invite me to please get in touch: [email protected] ******************************************************************** ******* OCC news: Oxfordshire Plan 2050 Consultation: A consultation has been launched on a plan that will set out how much new development there will be in Oxfordshire by 2050 and where this new development is located Oxfordshire County Council joins the UK100 to take on the climate emergency: UK100 is the only network for UK locally elected leaders who have pledged to play their part in the global effort to avoid the worst impacts of climate change by switching to 100% clean energy by 2050. -

SODC LP2033 2ND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT FINAL.Indd

South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT Appendix 5 Safeguarding Maps 209 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 210 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 211 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 212 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 213 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 214 216 Local Plan2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONSDOCUMENT South Oxfordshire DistrictCouncil South Oxfordshire South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 216 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 217 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 218 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 219 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 220 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS -

Bolney and Lashbrook Material for Article 4

BOLNEY AND LASHBROOK Beyond Domesday ……. To recap - at the time of the Domesday recording Shiplake was two medieval manors, Bolney and Lashbrook (with a smaller estate at Crowsley) Tenant in Chief of Lashbrook was Walter Giffard and he had made Hugh of Bolbec Lord of the Manor. Tenant in Chief of Bolney was Earl William and lord of the manor was Gilbert de Bretteville. Lashbrook 12 hides (approx 1440 acres) Bolney 8 hides (960 acres) 9 Ploughlands 7 Ploughlands 13 households 16 households. Bolney’s medieval manor house was probably (like its successor Shiplake Court/College) immediately next to Shiplake Church, and Lashbrook’s closer to the river at Lashbrook Farm. However, some parts of Bolney were contained in what is now Harpsden (The southern boundary with Shiplake followed the edge of High Wood before cutting across fields and following short stretches of field and woodland boundaries to the Thames) and there was a substantial manor house Bolney Court, also with a church, near the river. Bolney Manor (after doomsday) 1103 Son of Walter Giffard, also Walter, 2nd Earl of Buckingham, and Lord of Caversham took over when his father died. When, on his death he died without issue in 1164 The Langetot family – Ralph, then Emma and her husband Geoffrey Fitzwilliam owned the manor until in 1185 their daughter Muriel took control. She lived in Shiplake, probably at or near the site of the Shiplake Court (now Shiplake College). In 1209 Muriel’s two sons by her first husband, Alan de Dunstanville, were landowners. Firstly, Alan de Dunstanville and then when he died, his brother, Geoffrey. -

The Five Horseshoes Maidensgrove Leaflet.Pdf

How to get there Driving: Postcode is RG9 6EX with a car park for customers. Nearest station: Henley on Thames train stations is 6.4 miles away. Local bus services: We couldn’t find a bus service but if you know of one, please get in touch. We’re delighted to present three circular walks all starting and ending at The Five Horseshoes. The Brakspear Pub Trails are a series of circular walks. Brakspear would like We thought the idea of a variety of circular country walks to thank the Trust for all starting and ending at our pubs was a guaranteed Oxfordshire’s Environment winner. We have fantastic pubs nestled in the countryside, and the volunteers who helped make these walks possible. As a result of these and we hope our maps are a great way for you to get walks, Brakspear has invested in TOE2 to help maintain out and enjoy some fresh air and a gentle walk, with a and improve Oxfordshire’s footpaths. guaranteed drink at the end – perfect! Reg. charity no. 1140563 Our pubs have always welcomed walkers (and almost all of them welcome dogs too), so we’re making it even easier with plenty of free maps. You can pick up copies in the pubs taking part or go to brakspearaletrails.co.uk to download them. We’re planning to add new pubs onto Respect - Protect - Enjoy them, so the best place to check for the latest maps Respect other people: available is always our website. • Consider the local community and other people enjoying the outdoors We absolutely recommend you book a table so that when • Leave gates and property as you find them and follow you finish your walk you can enjoy a much needed bite to paths unless wider access is available eat too. -

U3a Historical Walks Nettlebed

U3A HISTORICAL WALKS NETTLEBED Start by the large square bus shelter in Nettlebed (GR702868) just off the A4130 road from Henley on Thames to Wallingford and Oxford. There is adequate parKing round The Green. Distance, about 4 miles, easy going. 1) By the bus shelter, note the board giving information about the Pudding Stones which are a geological feature. Then look behind at the restored late 17th century estate brick kiln, a reminder of the brick making industry that once flourished in Nettlebed. There is a very interesting information board. As you go through the village note the grey and silver bricks used everywhere; they are very hard, and the colour is due to the type of clay that covers the common. Nettlebed and its commons are a conservation area managed by the Nettlebed and District Commons Conservators. Now go along the minor road (called The Green) with houses on the left and The Green on the right. On reaching a junction with a grass triangle, turn sharp right at the sign to CrocKer End and Magpies. 2) Very soon turn sharp left on to track called “Catslip”. (Catslip = possibly, home of wild cats, slipe = Old English, muddy or slimy). There is also a “Catteslip House”. This was originally part of the Roman Road from Dorchester to London. You pass some attractive dwellings on the left in Arts and Crafts style. These were built for the workers at Joyce Grove (the local mansion). One of them is called Laundry Cottage and apparently was a Chinese laundry 3) Take a little narrow lane off to the left. -

TIMETABLE of RACING 1 8.30 Thames 31 Molesey BC

Thursday August 12th, 2021 - TIMETABLE OF RACING RaceTimeEvent Berks Bucks 1 8.30 Thames 31 Molesey B.C. 'B'v 44 The Tideway Scullers' School 2 8.35 Temple 85 Nottingham Universityv 74 Edinburgh University 3 8.40 Fawley 255 Exeter R.C.v 254 Enniskillen Royal B.C. 4 8.45 P. Wales 246 The Tideway Scullers' Schoolv 232 Edinburgh University & Strathclyde 5 8.50 Stonor 413 N. Gallagher & H. Youdv 421 R. Wilde & A. Hempleman Adams 6 9.00 Jubilee 306 Marlow R.C.v 299 Commercial R.C., IRL 7 9.05 Diamonds 437 S.J. Devereuxv WILL SCULL OV 8 9.10 Britannia 330 City of Oxford R.C.v 342 Nottingham R.C. 9 9.15 Fawley 296 York City R.C.v 267 Lea R.C. 10 9.20 Temple 89 Southampton Universityv 70 A.S.R. Nereus, NED 11 9.30 Britannia 345 The Tideway Scullers' Schoolv 340 Molesey B.C. 12 9.35 Stonor 416 J. Lindo & A. Hickenv 419 F.E. Snelling & E.I.D. Thomson 13 9.40 P. Wales 243 Reading University 'B'v 233 Hartpury University 14 9.45 PE 109 Bedford Modern Schoolv 115 King's College School 15 9.50 Thames 49 Upper Thames R.C. 'B'v 30 Molesey B.C. 'A' 16 10.00 Temple 73 Durham Universityv 97 U.S.R. Triton Laga, NED 17 10.05 PE 116 Monmouth Schoolv 122 St. Edward's School 18 10.10 Fawley 260 Hartpury Collegev 290 Wallingford R.C. 19 10.15 Jubilee 326 Wycliffe Junior R.C. -

16 STONOR GREEN Watlington | Oxfordshire 16 Stonor Green, Watlington Oxfordshire, OX49 5PT

16 STONOR GREEN Watlington | Oxfordshire 16 Stonor Green, Watlington Oxfordshire, OX49 5PT A handsome and beautifully presented six bedroom detached family house in Stonor Green one of the most favoured locations within the town For Sale Freehold Hall • Sitting Room • Dining Room Family Room • Kitchen/Breakfast Room Study • 6 Bedrooms 3 Bathrooms (1 en Suite) • Cloakroom Utility Room • Detached Double Garage Off Road Parking • South Facing Garden & Terrace • Double Glazing • Gas Central Heating •Security System M.40 (j6) 3 miles, Henley on Thames 10 miles, Oxford 14 miles, Wallingford 8 miles Description Stonor Green is a close of traditionally styled family homes and its situation gives some fine views towards the Chiltern escarpment. The house has attractive brick elevations under a clay tile roof with a south facing garden and a detached double garage alongside. It occupies a quiet landscaped cul-de-sac that makes an attractive street scene. The interior is well lit with generously proportioned rooms set around a central stairwell. A well fitted kitchen opens into a family dining room and the sitting room has an open fireplace and French doors that open to the garden. There are four bedrooms on the first floor including the master bedroom with en suite bathroom. A loft extension with dormer windows provides two further double bedrooms and a bathroom, all of which benefit from the fine views. Location Garden Watlington is an historic and attractive market South facing and enclosed by 6ft high close town at the foot of the Chiltern Hills. Apart from boarded fencing. Laid to lawn with some mature an ample range of local shops, facilities include a shrubs and ornamental trees. -

Fun Family Days out New Walks and Bike Rides

Outstanding Chilterns EXPLORE AND ENJOY IN 2016 Fun family days out New walks and bike rides GREAT DISCOVER FHIG T TO COUNTRYSIDE TASTY LOCAL PROTECT THE SITES TO VISIT TREATS CHILTERNS AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY 2 Outstanding Chilterns EXPLORE AND ENJOY IN 2016 AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Welcome to this new magazine published by the Chilterns www.chilternsaonb.org Conservation Board, full of inspiring ideas and information on The Chilterns AONB website has a enjoying the Chilterns Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 2016. wealth of information on the area, From great walks and bike rides to fun family days out, good including hundreds of downloadable walks and cycling routes, an interac- places to try tasty local food, wildlife conservation stories, quirky tive map highlighting places to visit attractions to visit and plenty more you’ll find it all in here! Discover and places to eat, a local events how to make the most of one of the UK’s finest areas of countryside listing and lots of information on the special features of the Chilterns. and how you can get involved in caring for it. Walking and Outstanding Chilterns is published 6-7 Cycling 4-5 annually by the Chilterns Conservation Board. Established in 2004, the Board A prescription is a public body with two key purposes: from Dr Nature 6-7 • To conserve and enhance the natural beauty of the Chilterns AONB Keeping it special 8 • To increase understanding and enjoyment of the special qualities of the AONB The water of life 9 In fulfilling these the Board also seeks to foster social and economic Tasting the 10 -11 well-being in local communities. -

GO Active Gold

GO Active Gold Helping rural villages become more active GO Active Gold encourages people in rural areas Bowls, Keep Fit Classes, Nordic age 60 and over, to live more active lifestyles, Walking, Pilates, Senior Circuits, by setting up more local physical activities that Table Tennis, Tai Chi, Tennis, Yoga, cater for all abilities. Zumba Gold Our project goals are: Get involved: • to improve the physical and mental • if you are a coach or instructor looking wellbeing of older adults to set up new classes for older people • to encourage stronger community spirit • if you would like to join an Active Thinking by reducing loneliness and social isolation group in your area to help plan new activities through participation in our activities • if you would like to receive training to • to develop a sustainable physical volunteer at one of many activites activity programme through training and supporting more coaches and volunteers Why your parish was chosen: With funding received from Sport England, we have • We chose parishes according to population employed rural Activators, to work in partnership with local size (approximately 500 - 3000 residents) communities to deliver a varied, inclusive and social physi- • Each parish has at least 100 cal activity programme. residents aged 60 and over • Many of the chosen parishes offered little or no appropriate physical PHYSICAL ACTIVITY RECOMMENDATIONS FOR OLDER activities for older people ADUlts PER WEEK • Aim to be active daily • 150 minutes of moderate intensity Our contact details: exercise - enough