2019 Anglin Carol Thesis.Pdf (1.106Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF 03/13/18 NEW Dances, a New Generation!

For IMMEDIATE Release: March 13, 2018 Press contacts: Melissa Thodos, Thodos Dance Chicago [email protected] Julie Nakagawa, DanceWorks Chicago [email protected] THODOS DANCE CHICAGO AND DANCEWORKS CHICAGO ANNOUNCE PARTNERSHIP TO PRESENT NEW DANCES 2018 CHICAGO– For over 30 years, New Dances has fostered new dance creation as one of Chicago’s first and most extensive in-house choreography incubation programs. Founded by The Chicago Repertory Dance Ensemble in the 1980’s and continued since 2000 by Thodos Dance Chicago, New Dances offers opportunities for emerging choreographers to realize and share their creative vision with the community. Today, Thodos Dance Chicago (TDC) and DanceWorks Chicago (DWC) announce a unique partnership to present New Dances 2018, continuing the annual tradition of developing choreographic talent and bringing New Dances home to its birthplace in the newly-renovated Ruth Page Center for the Arts. Melissa Thodos, Founder and Artistic Director of Thodos Dance Chicago shares, “We are so excited to be partnering with DanceWorks this season. Julie Nakagawa (Co-founder and Artistic Director of DanceWorks) and I share such a deep passion for developing young artists, both as dancers and choreographers. DanceWorks has such an incredible record of developing early career artists to rise to the next level. They are a perfect partner for this endeavor, and I believe New Dances will offer a level of quality and innovation never seen before.” "DanceWorks Chicago is thrilled to partner with Thodos Dance Chicago on New Dances 2018,” says Julie Nakagawa. “DWC values around cultivating a diverse next generation of movers and makers, engaging in community collaboration, offering mentorship, and sharing performances which shine a light on dancers and dances which makes New Dances a natural fit. -

Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018

Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018 Belvoir Terrace Staff 2018 Diane Goldberg Marcus - Director Educational Background D.M.A. City University of New York M.M. The Juilliard School B.M. Oberlin Conservatory Teaching/Working Experience American Camping Association Accreditation Visitor Private Studio Teacher - New York, NY Piano Instructor - Hunter College, New York, NY Vocal Coach Assistant - Hunter College, New York, NY Chamber Music Coach - Idyllwild School of Music, CA Substitute Chamber Music Coach - Juilliard Pre-College Division Awards/Publications/Exhibitions/Performances/Affiliations Married to Michael Marcus, Owner/Director of Camp Greylock, boys camp Becket, MA Independent School Liaison - Parents In Action, NYC Health & Parenting Association Coordinator - Trinity School, NYC American Camping Association Accreditation Visitor D.M.A. Dissertation: Piano Pedagogy in New York: Interviews with Four Master Teachers (Interviews with Herbert Stessin, Martin Canin, Gilbert Kalish, and Arkady Aronov) Teaching Fellowship - The City University of New York Honorary Scholarship for the Masters of Music Program – The Juilliard School The John N. Stern Scholarship - Aspen Music Festival Various Performances at: Paul Hall - Juilliard - New York Alice Tully Hall - New York City College - New York Berkshire Performing Arts Center, National Music Center - Lenox, MA WGBH Radio - Boston Reading Musical Foundation Museum Concert Series - Reading, PA Cancer Care Benefit Concert - Princeton, NJ Nancy Goldberg - Director Educational Background M.A. Harvard University -

2008–2009 Season Sponsors

2008–2009 Season Sponsors The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2008–2009 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. Season 08/09 YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Morris Bernstein Linda Dowell Ping Ho $50,001-$100,000 Norman Blanco Gloria Dumais Jon Howerton José Iturbi Foundation James Blevins Stanley Dzieminski Christina and Michael Hughes Michael Bley Lee Eakin Melvin Hughes Patron Kathleen Blomo Dee Eaton Marianne and Bob Hughlett, Ed.D. $20,001-$50,000 Marilyn Bogenschutz Susie Edber and Allen Grogan Mark Itzkowitz Linda and Sergio Bonetti Gary Edward Grace and Tom Izuhara National Endowment for the Arts Patricia Bongeorno Jill Edwards Sharon Jacoby Ilana and Allen Brackett Carla Ellis David Jaynes Partner Paula Briggs Robert Ellis Cathy and James Juliani $5,001-$20,000 Darrell Brooke Eric Eltinge Luanne Kamiya Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Mary Brough Teri Esposito Roland Kerby Chamber Music Society of Detroit Dr. -

Miami City Ballet 37

Miami City Ballet 37 MIAMI CITY BALLET Charleston Gaillard Center May 26, 2:00pm and 8:00pm; Martha and John M. Rivers May 27, 2:00pm Performance Hall Artistic Director Lourdes Lopez Conductor Gary Sheldon Piano Ciro Fodere and Francisco Rennó Spoleto Festival USA Orchestra 2 hours | Performed with two intermissions Walpurgisnacht Ballet (1980) Choreography George Balanchine © The George Balanchine Trust Music Charles Gounod Staging Ben Huys Costume Design Karinska Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Katia Carranza, Renato Penteado, Nathalia Arja Emily Bromberg, Ashley Knox Maya Collins, Samantha Hope Galler, Jordan-Elizabeth Long, Nicole Stalker Alaina Andersen, Julia Cinquemani, Mayumi Enokibara, Ellen Grocki, Petra Love, Suzette Logue, Grace Mullins, Lexie Overholt, Leanna Rinaldi, Helen Ruiz, Alyssa Schroeder, Christie Sciturro, Raechel Sparreo, Christina Spigner, Ella Titus, Ao Wang Pause Carousel Pas de Deux (1994) Choreography Sir Kenneth MacMillan Music Richard Rodgers, Arranged and Orchestrated by Martin Yates Staging Stacy Caddell Costume Design Bob Crowley Lighting Design John Hall Dancers Jennifer Lauren, Chase Swatosh Intermission Program continues on next page 38 Miami City Ballet Concerto DSCH (2008) Choreography Alexei Ratmansky Music Dmitri Shostakovich Staging Tatiana and Alexei Ratmansky Costume Design Holly Hynes Lighting Design Mark Stanley Dancers Simone Messmer, Nathalia Arja, Renan Cerdeiro, Chase Swatosh, Kleber Rebello Emily Bromberg and Didier Bramaz Lauren Fadeley and Shimon Ito Ashley Knox and Ariel Rose Samantha -

Elisa Monte Dance at 33 Years: 3 Premieres, 3 Choreogrpahers, 3 Days Only

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Kimberly Giannelli | Amber Henrie In The Lights PR [email protected] [email protected] Photos and video available on request ELISA MONTE DANCE AT 33 YEARS: 3 PREMIERES, 3 CHOREOGRPAHERS, 3 DAYS ONLY Diversity, Athleticism and Exploration Encompass the Three Premieres of Elisa Monte Dance. NEW YORK, April 24, 2014 — Elisa MontE DancE, an emotionally charged and highly acclaimed dance company that champions individuality, will celebrate its 33rd season with three world premieres in three days from May 15-17 at the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Artistic Director, Elisa MontE, will add to her collection of more than 50 works with the world premiere of Lonely Planet, the fourth and final movement in a succession of works that began in 2011. Additionally, Associate Artistic Director TiffAny REA-FishEr will present Persona Umbra in its New York premiere and long time EMD principal dancer and choreographer JoE CElEj will premiere their roots rest in infinity. The company will also restage Elisa Monte’s 1987 Audentity. “This season is a unique opportunity to share the vision of three dance makers in one program,” remarks founder and director Elisa Monte. “We are pushing into a future where collaborations and sharing ideas and processes are celebrated and cultivated to present an educated, healthy and creative voice to our audience.” Set to the music of David Van Teighem, Elisa Monte will premiere The Lonely Planet, a work that has taken a four-year journey. The work investigates the notable current issues of the rapid disappearance of language and culture in a society that is seemingly more technological. -

2021 Cityarts Grantees

2021 CITYARTS GRANTEES 2nd Story Chicago Jazz Philharmonic 3Arts, Inc. Chicago Kids Company 6018North Chicago Maritime Arts Center A.B.L.E. - Artists Breaking Limits & Expectations Chicago Media Project a.pe.ri.od.ic Chicago Public Art Group About Face Theatre Collective Chicago Shakespeare Theater Access Contemporary Music Chicago Sinfonietta Africa International House USA Chicago Tap Theatre Aguijon Theater Company Chicago West Community Music Center American Indian Center Chicago Youth Shakespeare Apparel Industry Board, Inc. Cinema/Chicago Art on Sedgwick Clinard Dance Arts Alliance Illinois Collaboraction Theatre Company Arts & Business Council of Chicago Collaborative Arts Institute of Chicago Arts of Life, Inc. Community Film Workshop of Chicago Asian Improv aRts: Midwest Community Television Network Avalanche Theatre Constellation Men's Ensemble Balzekas Museum of Lithuanian Culture Contextos Beverly Arts Center Court Theatre Beyond This Point Performing Arts Association Crossing Borders Music Black Alphabet Dance in the Parks, NFP Black Ensemble Theatre DanceWorks Chicago Black Lunch Table D-Composed Gives Cedille Chicago, NFP Definition Theatre Company Cerqua Rivera Dance Theatre Design Museum of Chicago Changing Worlds Erasing the Distance Chicago a cappella Fifth House Ensemble Chicago Architecture Foundation Filament Theatre Ensemble Chicago Art Department Forward Momentum Chicago Chicago Arts and Music Project Free Lunch Academy Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education Free Spirit Media Chicago Balinese Gamelan Free Street Theater Chicago Blues Revival FreshLens Chicago Chicago Cabaret Professionals Fulcrum Point New Music Project Chicago Childrens Choir Garfield Park Conservatory Alliance Chicago Composers Orchestra Global Girls Inc. Chicago Dance Crash Goodman Theatre Chicago Dancemakers Forum Guild Literary Complex Chicago Filmmakers Gus Giordano's Jazz Dance Chicago, Inc. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1989

National Endowment for the Arts Washington, D.C. Dear Mr. President: I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Council on the Arts for the Fiscal Year ended September 30, 1989. Respectfully, John E. Frohnmayer Chairman The President The White House Washington, D.C. July 1990 Contents CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT ............................iv THE AGENCY AND ITS FUNCTIONS ..............xxvii THE NATIONAL COUNCIL ON THE ARTS .......xxviii PROGRAMS ............................................... 1 Dance ........................................................2 Design Arts ................................................20 . Expansion Arts .............................................30 . Folk Arts ....................................................48 Inter-Arts ...................................................58 Literature ...................................................74 Media Arts: Film/Radio/Television ......................86 .... Museum.................................................... 100 Music ......................................................124 Opera-Musical Theater .....................................160 Theater ..................................................... 172 Visual Arts .................................................186 OFFICE FOR PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP ...............203 . Arts in Education ..........................................204 Local Programs ............................................212 States Program .............................................216 -

River North Dance Chicago

Cheryl Mann River North Dance Chicago Frank Chaves, Artistic Director • Gail Kalver, Executive Director The Company: Levizadik Buckins, Taeler Cyrus, Michael Gross, Hank Hunter, Lauren Kias, Ethan R. Kirschbaum, Melanie Manale-Hortin, Michael McDonald*, Hayley Meier, Olivia Rehrman, Ahmad Simmons, Jessica Wolfrum *Performing apprentice Artistic & Production Sara Bibik, Assistant to the Artistic Director • Claire Bataille, Ballet Mistress Joshua Paul Weckesser, Production Stage Manager and Technical Director Mari Jo Irbe, Rehearsal Director • Laura Wade, Ballet Mistress Liz Rench, Wardrobe Supervisor Administration Alexis Jaworski, Director of Marketing • Salena Watkins, Business Manager Diana Anton, Education Manager • Paula Petrini Lynch, Development Manager Christopher W. Frerichs, Grant Writer Lisa Kudo, Development and Special Events Assistant PROGRAM The Good Goodbyes Beat Eva (World Premiere) -Intermission- Three Renatus Forbidden Boundaries Thursday, April 4 at 7:30 PM Friday, April 5 at 8 PM Saturday, April 6 at 2 PM & 8 PM Media support for these performances is provided by WHYY. 12/13 Season | 23 PROGRAM The Good Goodbyes Choreography: Frank Chaves Lighting Design: Todd Clark Music: Original composition by Josephine Lee Costume Design: Jordan Ross Dancers: Taeler Cyrus, Michael Gross, Lauren Kias, Ethan R. Kirschbaum, Melanie Manale-Hortin, Hayley Meier, Jessica Wolfrum Artistic Director Frank Chaves’ newest work, The Good Goodbyes, is an homage to the relationships forged and nurtured within the dance community. Set to an original piano suite by Josephine Lee, artistic director of the acclaimed Chicago Children’s Choir, this wistful and bittersweet work for seven dancers suggests “the beautiful memories and the wonderful relationships I’ve forged with dancers over the years. I want to celebrate the incredibly intimate, intense, fulfilling and—because of the nature of our profession—often short-lived connections we’ve made, and have bid goodbye along the way,” says Chaves. -

Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro Zone)

edition ENGLISH n° 284 • the international DANCE magazine TOM 650 CFP) Pina Forever • UK 5,00 £ Switzerland 8,00 CHF USA $ Canada 7,00 $; (Euro zone) € 4,90 9 10 3 4 Editor-in-chief Alfio Agostini Contributors/writers the international dance magazine Erik Aschengreen Leonetta Bentivoglio ENGLISH Edition Donatella Bertozzi Valeria Crippa Clement Crisp Gerald Dowler Marinella Guatterini Elisa Guzzo Vaccarino Marc Haegeman Anna Kisselgoff Dieudonné Korolakina Kevin Ng Jean Pierre Pastori Martine Planells Olga Rozanova On the cover, Pina Bausch’s final Roger Salas work (2009) “Como el musguito en Sonia Schoonejans la piedra, ay, sí, sí, sí...” René Sirvin dancer Anna Wehsarg, Tanztheater Lilo Weber Wuppertal, Santiago de Chile, 2009. Photo © Ninni Romeo Editorial assistant Cristiano Merlo Translations Simonetta Allder Cristiano Merlo 6 News – from the dance world Editorial services, design, web Luca Ruzza 22 On the cover : Advertising Pina Forever [email protected] ph. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Bluebeard in the #Metoo era (+39) 011.19.58.20.38 Subscriptions 30 On stage, critics : [email protected] The Royal Ballet, London n° 284 - II. 2020 Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo Hamburg Ballet: “Duse” Hamburg Ballet, John Neumeier Het Nationale Ballet, Amsterdam English National Ballet Paul Taylor Dance Company São Paulo Dance Company La Scala Ballet, Milan Staatsballett Berlin Stanislavsky Ballet, Moscow Cannes Jeune Ballet Het Nationale Ballet: “Frida” BALLET 2000 New Adventures/Matthew Bourne B.P. 1283 – 06005 Nice cedex 01 – F tél. (+33) 09.82.29.82.84 Teac Damse/Keegan Dolan Éditions Ballet 2000 Sarl – France 47 Prix de Lausanne ISSN 2493-3880 (English Edition) Commission Paritaire P.A.P. -

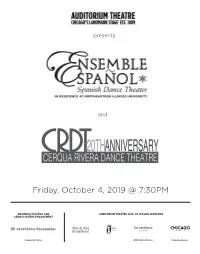

AUD 2019-20 WRAP 1 Program 3 Ensemble Espanol 091719.Indd

presents and Friday, October 4, 2019 @ 7:30PM ~ ENSEMBLE ESPANOL AND AUDITORIUM THEATRE 2019–20 SEASON SPONSORS CERQUA RIVERA ENGAGEMENT Community Partner Official Hotel Partner Magazine Sponsor PROGRAM CERQUA RIVERA DANCE THEATRE American Catracho The American Catracho suite is the culmination of a three-year exploration of immigration that involved over three dozen artists and other collaborators, including hundreds of audience members. Inspired by Cerqua Rivera cofounder and Artistic Director Wilfredo Rivera’s own personal journey, the four-part piece moves through themes of dislocation, assimilation, renewal, and hope. Part I Memories Behind The Crossing Part II First 200 Feet Part III Mi America Part IV Land of Dreams Creator and Director: Wilfredo Rivera Original Music: Joe Cerqua (with introduction by James Sanders) and “Fijate Bien” by Juanes, arranged by Stu Greenspan Additional Choreography: Noelle Kayser, Christian Denice Costume Design: Jordan Ross Lighting Design: David Goodman-Edberg Projection Design: Simean Carpenter Additional Collaborators: Lewis Achenbach (painter), Charin Alvarez (actor), Laura Crotte (actor), Julian Hester (actor), Cecilie Keenan (theatre artist), Ethan Kirschbaum (movement consultant), Shawn Lent (dancer educator and immigration activist), Kristi Licera (movement consultant), Dr. Daniel Michaud-Novak (psychologist), Myesha-Tiara (actor) Creation of American Catracho is sponsored by The Cliff Dwellers Arts Foundation and The Saints. ENSEMBLE ESPAÑOL SPANISH DANCE THEATER Ecos De España (Echoes of Spain) The inexhaustible vitality and distinctly individual qualities of Spanish folk music, with all its rhythms and colors, have fascinated composers in Europe and worldwide throughout the 20th century. Ensemble Espanol� founder Dame Libby Komaiko was inspired by paintings from Francisco de Goya’s “Black Period” and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s musical creations. -

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS JUDITH JAMISON, Artistic Director

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS March 9–14, 2004 Zellerbach Hall Alvin Ailey, founder JUDITH JAMISON, artistic director Masazumi Chaya, associate artistic director Company Members Clyde Archer, Guillermo Asca, Olivia Bowman, Hope Boykin, Clifton Brown, Samuel Deshauteurs, Antonio Douthit, Linda-Denise Fisher-Harrell, Jeffrey Gerodias, Vernard J. Gilmore, Venus Hall, Abdur-Rahim Jackson, Amos J. Machanic, Jr., Benoit-Swan Pouffer, Briana Reed, Jamar Roberts, Renee Robinson, Laura Rossini, Cheryl Rowley-Gaskins, Matthew Rushing, Rosalyn Sanders, Wendy White Sasser, Bahiyah Sayyed-Gaines, Glenn A. Sims, Linda Celeste Sims, Dwana Adiaha Smallwood, Asha Thomas, Tina Monica Williams, Dion Wilson, and Dudley Williams Sharon Gersten Luckman, executive director Major funding is provided by the New York State Council on the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, the National Endowment for the Arts, Altria Group, Inc., MasterCard International, and The Shubert Foundation. American Airlines is the official airline of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. National Sponsor of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater These performances by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater are sponsored, in part, by Wells Fargo. Additional support for Cal Performances’ presentation of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts and the Friends of Cal Performances. Cal Performances thanks the Zellerbach Family Foundation, ChevronTexaco, Citigroup, Macy’s West, McKesson Foundation, and Pacific Union Real Estate for -

A Study on the Gender Imbalance Among Professional Choreographers Working in the Fields of Classical Ballet and Contemporary Dance

Where are the female choreographers? A study on the gender imbalance among professional choreographers working in the fields of classical ballet and contemporary dance. Jessica Teague August 2016 This Dissertation is submitted to City University as part of the requirements for the award of MA Culture, Policy and Management 1 Abstract The dissertation investigates the lack of women working as professional choreographers in both the UK and the wider international dance sector. Although dance as an art form within western cultures is often perceived as ‘the art of women,’ it is predominately men who are conceptualising the works and choreographing the movement. This study focuses on understanding the phenomenon that leads female choreographers to be less likely to produce works for leading dance companies and venues than their male counterparts. The research investigates the current scope of the gender imbalance in the professional choreographic field, the reasons for the imbalance and provides theories as to why the imbalance is more pronounced in the classical ballet sector compared to the contemporary dance field. The research draws together experiences and statistical evidence from two significant branches of the artistic process; the choreographers involved in creating dance and the Gatekeepers and organisations that commission them. Key issues surrounding the problem are identified and assessed through qualitative data drawn from interviews with nine professional female choreographers. A statistical analysis of the repertoire choices of 32 leading international dance companies quantifies and compares the severity of the gender imbalance at the highest professional level. The data indicates that the scope of the phenomenon affects not only the UK but also the majority of the Western world.