On Writing and Handwriting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Format Guide

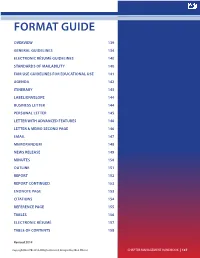

FORMAT GUIDE OVERVIEW 139 GENERAL GUIDELINES 134 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ GUIDELINES 140 STANDARDS OF MAILABILITY 140 FAIR USE GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATIONAL USE 141 AGENDA 142 ITINERARY 143 LABEL/ENVELOPE 144 BUSINESS LETTER 144 PERSONAL LETTER 145 LETTER WITH ADVANCED FEATURES 146 LETTER & MEMO SECOND PAGE 146 EMAIL 147 MEMORANDUM 148 NEWS RELEASE 149 MINUTES 150 OUTLINE 151 REPORT 152 REPORT CONTINUED 153 ENDNOTE PAGE 153 CITATIONS 154 REFERENCE PAGE 155 TABLES 156 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ 157 TABLE OF CONTENTS 158 Revised 2014 Copyright FBLA-PBL 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by: FBLA-PBL, Inc CHAPTER MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK | 137 138 | FBLA-PBL.ORG OVERVIEW In today’s business world, communication is consistently expressed through writing. Successful businesses require a consistent message throughout the organization. A foundation of this strategy is the use of a format guide, which enables a corporation to maintain a uniform image through all its communications. Use this guide to prepare for Computer Applications and Word Processing skill events. GENERAL GUIDELINES Font Size: 11 or 12 Font Style: Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Cambria Spacing: 1 space after punctuation ending a sentence (stay consistent within the document) 1 space after a semicolon 1 space after a comma 1 space after a colon (stay consistent within the document) 1 space between state abbreviation and zip code Letters: Block Style with Open Punctuation Top Margin: 2 inches Side and Bottom Margins: 1 inch Bulleted Lists: Single space individual items; double space between items -

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques A dissertation submitted to Birmingham City University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art and Design By: Ahmad Saleh A. Almontasheri Director of the study: Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi 2017 1 Dedication My great mother, your constant wishes and prayers were accepted. Sadly, you will not hear of this success. Happily, you are always in the scene; in the depth of my heart. May Allah have mercy on your soul. Your faithful son: Ahmad 2 Acknowledgments I especially would like to express my appreciation of my supervisors, the director of this study, Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi, and the second supervisor Dr. Mohsen Keiany. As mentors, you have been invaluable to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to you all for encouraging me to conduct this research and give your valuable time, recommendations and support. The advice you have given me, both in my research and personal life, has been priceless. I am also thankful to the external and internal examiners for their acceptance and for their feedback, which made my defence a truly enjoyable moment, and also for their comments and suggestions. Prayers and wishes would go to the soul of my great mother, Fatimah Almontasheri, and my brother, Abdul Rahman, who were the first supporters from the outset of my study. May Allah have mercy on them. I would like to extend my thanks to my teachers Saad Saleh Almontasheri and Sulaiman Yahya Alhifdhi who supported me financially and emotionally during the research. -

The Selnolig Package: Selective Suppression of Typographic Ligatures*

The selnolig package: Selective suppression of typographic ligatures* Mico Loretan† 2015/10/26 Abstract The selnolig package suppresses typographic ligatures selectively, i.e., based on predefined search patterns. The search patterns focus on ligatures deemed inappropriate because they span morpheme boundaries. For example, the word shelfful, which is mentioned in the TEXbook as a word for which the ff ligature might be inappropriate, is automatically typeset as shelfful rather than as shelfful. For English and German language documents, the selnolig package provides extensive rules for the selective suppression of so-called “common” ligatures. These comprise the ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl ligatures as well as the ft and fft ligatures. Other f-ligatures, such as fb, fh, fj and fk, are suppressed globally, while making exceptions for names and words of non-English/German origin, such as Kafka and fjord. For English language documents, the package further provides ligature suppression rules for a number of so-called “discretionary” or “rare” ligatures, such as ct, st, and sp. The selnolig package requires use of the LuaLATEX format provided by a recent TEX distribution, e.g., TEXLive 2013 and MiKTEX 2.9. Contents 1 Introduction ........................................... 1 2 I’m in a hurry! How do I start using this package? . 3 2.1 How do I load the selnolig package? . 3 2.2 Any hints on how to get started with LuaLATEX?...................... 4 2.3 Anything else I need to do or know? . 5 3 The selnolig package’s approach to breaking up ligatures . 6 3.1 Free, derivational, and inflectional morphemes . -

Manuscripts Form Explanatory Notes.Pdf

1 Explanatory notes:1 Form for additions or corrections to PhiloBiblon MANUSCRIPTS Information related to manuscript description is available on any PhiloBiblon HELP page: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_es.html (BETA) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_po.html (BITAGAP) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_ga.html (BITAGAP) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_ca.html (BITECA) For codicological terminology, see Denis Muzerelle’s site (http://codicologia.irht.cnrs.fr ). For terminology in Portuguese, consult Maria Isabel Faria and Maria da Graça Pericão’s Dicionário do Livro. Da escrita ao livro electrónico, Coimbra: Almedina, 2008. (BITAGAP bibid 12314). Links to many databases relevant to manuscript description (bindings, codicology, paleography, ruling, watermarks, seals, etc.) appear in PhiloBiblon online, in RESOURCES. Bookmark this page in all of your browsers to facilitate quick consultation of useful resources. For the purposes of filling out this form, the term “manuscript” refers to the physical object in which a text is written, whether a book/codex or a loose piece of parchment. A manuscript might consist of hundreds of bound leaves, five gatherings, or a single sheet of paper. The term “manuscript” is used here for all of these. A factitious manuscript is comprised of several parts or sections of different provenance. It can include codicologically distinct quires (parchment and paper), leaves or gatherings copied in different eras, printed texts, etc. A separate form with a detailed description must be prepared for each part of the manuscript that contains an appropriate text for the relevant bibliography. Information for the entire manuscript is included only in the record for the first part, which has a manid. -

Building Other Custom Screens

Building Other Custom Screens Overview Advanced Custom Forms Overview Advanced Custom Forms provide you more control over the look and layout of the form that users will be accessing to enter data. You can access Advanced Custom Forms by expanding the Custom Form from the Custom Form main screen. Advanced Custom Forms To begin building an Advanced Custom Forms screen, click the Add Advanced Form link. The Advanced Custom Form Maintenance screen will display. Enter a Name for the screen and begin adding content to the form. We will now review one section at a time, as well as the buttons/options on the Advanced Custom Form Maintenance screen. System: This field cannot be edited. It is based on the type of Custom Form you are working in. Name: This is the name of the Advanced Custom Form and is the name that users will see when trying to access the information. Layout: Click this button to toggle the orientation of the form between Portrait (the default) or Landscape. This effects how the form will print when sent to a printer. Table: The options under here are to be used if using a table on the form. You would want your cursor placed in the row you wish to work with, and then you can select to Clone a Row, Delete a Row, or Delete to Last Row which will remove the row with your cursor, and all rows of the table below it. Fields: This is where you can access all of the available Skyward fields and Custom Fields created for the form and choose to add them to your form. -

The Deer Scroll by Kōetsu and Sōtatsu

The Deer Scroll by Kōetsu and Sōtatsu Reappraised Golden Week Lecture Series— Four Masterpieces of Japanese Painting: A Symposium Miyeko Murase, Former Consultant for Japanese Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Takeo and Itsuko Atsumi Professor Emerita, Columbia University Poem Scroll with Deer (part), Hon’ami Kōestu and Tawaraya Sōtatsu, early 17th century, handscroll, ink, gold and silver on paper, 13 3/8 x 372 in., Gift of Mrs. E. Frederick, 51.127 It has been quite some years since I last spoke here at this museum, so many in fact that I have lost count. It is really wonderful to be back, and I want to thank director Mimi Gates and curator Yukiko Shirahara, who invited me to speak today on the world-famous Deer Scroll by Sōtatsu and Kōetsu. This proud possession of the Seattle Art Museum is one of the most beautiful paintings ever created by Japanese artists.1 The scroll just came back from Japan after extensive restorative work. Although the handscroll itself does not bear any title, it is generally known as the Deer Scroll because the entire scroll is filled with images of deer, which are shown either singly, in couples, or in large herds. The animals are painted only in gold and/or silver ink, as is the very simple setting of sky, mist, and ground. As you may have noticed, these beautiful pictures of deer are really a background for the equally exquisite writings of waka poems in black ink. Here we have a symphony of three arts - poetry, painting, and calligraphy - as a testimonial to the ancient credo of Asia that these three arts occupy an equally important place in life and culture. -

GAMUT Editor Aids

GAMUT Editor Aids // 1 // SYMBOLS OF THE UPPER TOOLBAR // WITH THESE SYMBOLS . YOU TRIGGER THESE ACTIONS » Font Size » Use the dropdown to select the font size » Text Color » Change the color of the selected text » Background Color » Change the background color (highlight) of the selected text » Bold » Apply bold formatting to the selected text » Italic » Apply italic formatting to the selected text » Underline » Apply underline formatting to the selected text » Strikethrough » Apply strikethrough formatting to the selected text » Subscript » Make text or numbers appear as subscript » Superscript » Make text or numbers appear as superscript continued // 2 // SYMBOLS OF THE UPPER TOOLBAR // WITH THESE SYMBOLS . YOU TRIGGER THESE ACTIONS » Copy Formatting » Copy the formatting from one area of text and apply it to another » Remove Format » Remove the formatting from the selected area of tex » The starting number of the list can also be changed here. » Numbered List » Select this button to begin a numbered list. » Bulleted List » Select this button to begin a bulleted list. » To change the numbered list properties, right click in the list and make a selection from the following: » The starting number of the list can also be changed here. continued // 3 // SYMBOLS OF THE UPPER TOOLBAR // WITH THESE SYMBOLS . YOU TRIGGER THESE ACTIONS » Bulleted List, continued » To change the bulleted list properties, right click in the list and make a selection from the following: » Decrease Indent » Decrease the paragraph indent to the left » Increase -

Headers and Footers in Microsoft Word South Puget Sound Community College Student Computing Center Written By: Chris Dorn

Headers and Footers in Microsoft Word South Puget Sound Community College Student Computing Center Written by: Chris Dorn A header is the top margin of each page, and a footer is the bottom margin of each page. Headers and footers are useful for including material that you want to appear on every page of a document such as your name, the title of the document, or page numbers. This tutorial explains how to insert headers and footers, how to have a different header on the first page, and how to create different headers in different sections. Inserting Headers and Footers To insert a header or footer, first go to the Insert tab and select the desired option. Clicking either of these icons will display a dropdown menu with several options. SPSCC Student Computing Center__Headers and Footers __1 If you just want to add a simple header such as a title or your last name, you can choose the first option. This will bring the cursor into the header. Notice, too, that a new tab appears on the ribbon. This Design tab allows you to change certain features of the header such as the header position and page number. Design tab You can type here Once you are in the top (or bottom) margin, you can change the text formatting of the header (or footer) the same way that you would change formatting in the body of the document. For instance, if you want to center your header, you can go to the Home tab and select the center alignment icon in the Paragraph group, as pictured below: Centered header SPSCC Student Computing Center__Headers and Footers __2 Having a Different First Page Header Sometimes you may be asked to have a header that does not appear on the first page. -

Opentype in Context Multi--Dimensional Font Support and Advanced Font Features

52 MAPS 31 Adam T. Lindsay OpenType in ConTEXt Multi--dimensional font support and advanced font features Keywords ConTeXt fonts OpenType Abstract This is a summary of issues encountered and solutions implemented in order to support some advanced OpenType features in ConTEXt. This article describes an accompanying set of support files that address installation (using TEXFONT), accommodating extended opticals families, and some “pro” font features. The extended character set afforded by pro fonts enables support for comprehensive small caps and old--style figures. Although the typescripts and commands are described together, certain features (like variant encodings for TEXFONTand optical typescripts) can be used independently of the other features described. Introduction This article, originally produced as a ConTEXt “My Way” article, introduces some issues in installing, using, and integrating OpenType fonts in ConTEXt. OpenType has been discussed elsewhere in detail, but it should suffice to say that it is a modern melding of POSTSCRIPT and TrueType, enabling advanced typography features and Unicode support. Roman and With some of the most complex OpenType fonts, one also sees integration with C multiple design sizes. This is not necessarily unique to OpenType fonts, but is a co-- ItalicC and occurring feature seen with “premium”--quality fonts. Some of the advanced typo- Bold and graphical features seen in such fonts are integrated glyphs for small caps (across C every font variant), old style and tabulation figures, and greek glyphs, all within BoldIC the same font. This article introduces some strategies for taking advantage of small Figure 1 Small caps in caps and old style figures, and for rudimentary math fonts for fonts that include several variants greek language support. -

Calligraphy-Magic.Pdf

Calligraphy Magic How to Create Lettering, Knotwork, Coloring and More Cari Buziak Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction Glossary of Terms CHAPTER 1 Calligraphy Tools and Supplies CHAPTER 2 How to Make Calligraphy Strokes CHAPTER 3 15 Alphabets From Basic to Fancy CHAPTER 4 Ornamentation, Gilding & Coloring CHAPTER 5 12 Calligraphy Projects Step by Step STATIONERY AND EVENT ANNOUNCEMENTS Bookplates Greeting Cards Bookmarks Logos Business Cards and Letterhead Wedding Announcements Invitations Place Cards and Thank-You’s DISPLAY PIECES Monograms Quotations Certifi cates Lettering with Celtic Decoration Illustrated Poems Lettering with Dragon Artwork CHAPTER 6 Creating Your Own Computer Fonts Pre-printed Celtic Knotwork Grid Paper Pre-ruled Calligraphy Practice Pages Index About the Author Dedication Acknowledgments Introduction Introduction Calligraphy is a fun craft to learn, as well as a useful one. Far from being an obsolete skill, more and more people today are picking up the pen and creating their own greeting cards, wedding invitations, fine art projects, and even creating their own computer fonts! In the old days, calligraphy tools were unique and specically crafted to their task. Today, a calligrapher has a wide variety of tools from which to choose, from traditional to completely modern, even digital! Calligraphers can now experiment with their artistic expression, freely mixing creative ideas and elements together to explore new artforms with their projects. In this book we’ll examine the basic techniques of calligraphy, covering calligraphy hands suitable for a wide variety of projects and easy for a beginner or intermediate calligrapher to practice and learn. We’ll also cover easy decorative techniques such as watercolor painting, Celtic knotwork, gold leang and illustration ideas to create a “toolkit” of creative techniques. -

MS Word Tips and Tricks

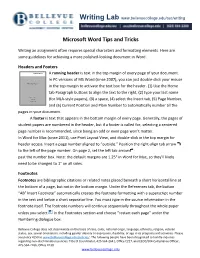

Writing Lab www.bellevuecollege.edu/asc/writing Microsoft Word Tips and Tricks Writing an assignment often requires special characters and formatting elements. Here are some guidelines for achieving a more polished-looking document in Word. Headers and Footers A running header is text in the top margin of every page of your document. In PC versions of MS Word (since 2007), you can just double-click your mouse in the top margin to activate the text box for the header. (1) Use the Home tab Paragraph buttons to align the text to the right, (2) type your last name (for MLA-style papers), (3) a space, (4) select the Insert tab, (5) Page Number, and (6) Current Position and Plain Number to automatically number all the pages in your document. A footer is text that appears in the bottom margin of every page. Generally, the pages of student papers are numbered in the header, but if a footer is called for, selecting a centered page number is recommended, since being an odd or even page won’t matter. In Word for Mac (since 2011), use Print Layout View, and double-click in the top margin for header access. Insert a page number aligned to “outside.” Position the right-align tab arrow to the left of the page number. On page 2, set the left tab arrow past the number box. Note: the default margins are 1.25" in Word for Mac, so they’ll likely need to be changed to 1" on all sides. Footnotes Footnotes are bibliographic citations or related notes placed beneath a short horizontal line at the bottom of a page, but not in the bottom margin. -

Font Handling in Troff with Postscript Devices

Fo tn Hand gnil ni rT o With PostS irc pt D ve ices FONT HAND IL NG IN TROFF WITH POSTSCR PI T DEVICES GIAA4F R<HH8F op /qs/ou a Heirloom Docume tn ation Tools <h tt p://heirloom.sourceforge.net/doctools.html> T eh bas sic Heirloom rt o understands two ways ot select PostS irc pt fo .stn The cu tnerr method can access PostS irc pt fo tn les erid ct .ly Fo stn are select de usi gn an ex et nded .f‘‘ ’’p qer uest. As simple examples, .fp 0 AG gdrg____ pfb t.f AG H ere is some tex nit Adobe Garamond Regular. ro .fp 0 AG AGaramondP R-or egular otf t.f AG H ere is some tex nit Adobe Garamond orP Regular. B tu it is also possible ot have die tner names for the metrics and glyph data les, as ni .fp 0 AM myk gninre .afm gdrg____.pfb t.f AM This text nistnirp Adobe Garamond usi gn modified .gninrek The defau tl highe r-r esol tu ion ‘‘ps’’ PostS irc pt device always uses AFM les; it us pp stro the co tnevn ional .f‘‘ ’’p qer uest for backwards compatibil- ity ot select rp tsnie- alled fo stn from the PDF base set. With fo stn select de yb ht is metho ,d localized ni put orp cessi gn is -rep formed acco gnidr ot the LC_CTYPE orivne nme tn variable, ro acco gnidr ot a docume -stn ep cic value set yb the ‘‘.lc_ctype’’ qer ues :t .\" Enable lo gn qer uest names.