The Deer Scroll by Kōetsu and Sōtatsu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Format Guide

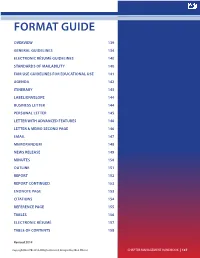

FORMAT GUIDE OVERVIEW 139 GENERAL GUIDELINES 134 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ GUIDELINES 140 STANDARDS OF MAILABILITY 140 FAIR USE GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATIONAL USE 141 AGENDA 142 ITINERARY 143 LABEL/ENVELOPE 144 BUSINESS LETTER 144 PERSONAL LETTER 145 LETTER WITH ADVANCED FEATURES 146 LETTER & MEMO SECOND PAGE 146 EMAIL 147 MEMORANDUM 148 NEWS RELEASE 149 MINUTES 150 OUTLINE 151 REPORT 152 REPORT CONTINUED 153 ENDNOTE PAGE 153 CITATIONS 154 REFERENCE PAGE 155 TABLES 156 ELECTRONIC RÉSUMÉ 157 TABLE OF CONTENTS 158 Revised 2014 Copyright FBLA-PBL 2014. All Rights Reserved. Designed by: FBLA-PBL, Inc CHAPTER MANAGEMENT HANDBOOK | 137 138 | FBLA-PBL.ORG OVERVIEW In today’s business world, communication is consistently expressed through writing. Successful businesses require a consistent message throughout the organization. A foundation of this strategy is the use of a format guide, which enables a corporation to maintain a uniform image through all its communications. Use this guide to prepare for Computer Applications and Word Processing skill events. GENERAL GUIDELINES Font Size: 11 or 12 Font Style: Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, or Cambria Spacing: 1 space after punctuation ending a sentence (stay consistent within the document) 1 space after a semicolon 1 space after a comma 1 space after a colon (stay consistent within the document) 1 space between state abbreviation and zip code Letters: Block Style with Open Punctuation Top Margin: 2 inches Side and Bottom Margins: 1 inch Bulleted Lists: Single space individual items; double space between items -

Exhibition Schedule

November 8 (Sun.) - December 13 (Sun.), 2020 Special Exhibits at the Masterpieces Collection Room 2 Thematic Exhibition February 20 - March 2, 2021 Reading and Re-envisioning The Tale of Genji Tea Scoop, named Namida ("Tears") 2020 - 2021 through the Ages It is said that Sen-no-Rikyū (1522-1591), in April March Exhibition Rooms at Hōsa Library his last days, carved this bamboo tea scoop and used it in his last tea gathering, after Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598) The Tale of Genji written by Murasaki Shikibu is a masterpiece of classic ordered punishment upon him. March 28, the day of Rikyū's death, literature that has been read continuously over the course of a thousand is remembered as a memorial day called "Rikyū-ki." The scoop was Exhibition Schedule years. The National Treasure The Diary of later owned by Furuta Oribe who made the outer case for the scoop, Murasaki Shikibu Illustrated Handscroll in the then by Tokugawa Ieyasu and by the 1st Owari Lord Tokugawa THE TOKUGAWA ART MUSEUM collection of Gotoh Museum, Tokyo, will be on Yoshinao. HŌSA LIBRARY CITY of NAGOYA special exhibit and this exhibition will unravel the charm of Japan’s world-famous Tale of February 6 (Sat.) - April 4 (Sun.), 2021 Genji by tracing the cultural history pertaining to the tale. Special Exhibition The Doll Festival of the Owari Tokugawa <Chapter "Kiritsubo" from the Tale of Genji> Edo period, 1655 Family Private Collection Exhibition Rooms 7-9 at The Tokugawa Art Museum Special Exhibits at the Masterpieces Collection Room 5 Focused on the Hina dolls and doll accessories passed down in the Owari November 8 - December 13, 2020 Tokugawa family, this exhibition presents the extravagant and refined world of dolls that is The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu Illustrated Handscroll (designated a distinctive of an elite daimyō family. -

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques

The Transformation of Calligraphy from Spirituality to Materialism in Contemporary Saudi Arabian Mosques A dissertation submitted to Birmingham City University in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art and Design By: Ahmad Saleh A. Almontasheri Director of the study: Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi 2017 1 Dedication My great mother, your constant wishes and prayers were accepted. Sadly, you will not hear of this success. Happily, you are always in the scene; in the depth of my heart. May Allah have mercy on your soul. Your faithful son: Ahmad 2 Acknowledgments I especially would like to express my appreciation of my supervisors, the director of this study, Professor Mohsen Aboutorabi, and the second supervisor Dr. Mohsen Keiany. As mentors, you have been invaluable to me. I would like to extend my gratitude to you all for encouraging me to conduct this research and give your valuable time, recommendations and support. The advice you have given me, both in my research and personal life, has been priceless. I am also thankful to the external and internal examiners for their acceptance and for their feedback, which made my defence a truly enjoyable moment, and also for their comments and suggestions. Prayers and wishes would go to the soul of my great mother, Fatimah Almontasheri, and my brother, Abdul Rahman, who were the first supporters from the outset of my study. May Allah have mercy on them. I would like to extend my thanks to my teachers Saad Saleh Almontasheri and Sulaiman Yahya Alhifdhi who supported me financially and emotionally during the research. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Reading and Re-Envisioning the Tale of Genji Through the Ages

Symbols of each chapters of The Tale of Genji Thematic Exhibition Ⅳ Dissemination of the Genji Tale from the Genji-kō Incense Game Reading and Re-envisioning The Tale of Genji attracted many readers, irrespective of gender, through "Genji-kō" is a name of the kumikō incense game which is tasting different the beauty of the text and its thorough depictions fragrances and guessing the name, developed in Edo period. Participants The Tale of Genji of every aspect of classical court culture, its skillful would taste 5 different fragrances and draw a horizontal line to connect the psychological portrayals of the characters, and same fragrance. Thus drawn, figures appear in 52 different shapes, matching through the Ages its diverse world view based on Japanese the number of chapters of The Tale of Genji except the first and the last ones, and Chinese literature, various arts, and and they are called "Genji-kō" design. The "Genji-kō" design often appears in Buddhism. Not only did it have a significant impact on various traditional craft works as well as design of Japanese confectionery later literary works, but its influence can also be seen in associated with the story of The Tale of Genji. Japanese performing arts, such as Noh theater, and cultural arts, such as incense ceremony (kōdō), and tea ceremony (sadō), as well as the arts and crafts that accompany them. 46 37 28 1 9 1 0 1 “The Tale of Genji,” written Shiigamoto Yokobue Nowaki Usugumo Sakaki Kiritsubo At the same time, as a narrative that features Art Museum & The Tokugawa 2020 / By Hōsa Library, City of Nagoya Nov. -

The Selnolig Package: Selective Suppression of Typographic Ligatures*

The selnolig package: Selective suppression of typographic ligatures* Mico Loretan† 2015/10/26 Abstract The selnolig package suppresses typographic ligatures selectively, i.e., based on predefined search patterns. The search patterns focus on ligatures deemed inappropriate because they span morpheme boundaries. For example, the word shelfful, which is mentioned in the TEXbook as a word for which the ff ligature might be inappropriate, is automatically typeset as shelfful rather than as shelfful. For English and German language documents, the selnolig package provides extensive rules for the selective suppression of so-called “common” ligatures. These comprise the ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl ligatures as well as the ft and fft ligatures. Other f-ligatures, such as fb, fh, fj and fk, are suppressed globally, while making exceptions for names and words of non-English/German origin, such as Kafka and fjord. For English language documents, the package further provides ligature suppression rules for a number of so-called “discretionary” or “rare” ligatures, such as ct, st, and sp. The selnolig package requires use of the LuaLATEX format provided by a recent TEX distribution, e.g., TEXLive 2013 and MiKTEX 2.9. Contents 1 Introduction ........................................... 1 2 I’m in a hurry! How do I start using this package? . 3 2.1 How do I load the selnolig package? . 3 2.2 Any hints on how to get started with LuaLATEX?...................... 4 2.3 Anything else I need to do or know? . 5 3 The selnolig package’s approach to breaking up ligatures . 6 3.1 Free, derivational, and inflectional morphemes . -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

Manuscripts Form Explanatory Notes.Pdf

1 Explanatory notes:1 Form for additions or corrections to PhiloBiblon MANUSCRIPTS Information related to manuscript description is available on any PhiloBiblon HELP page: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_es.html (BETA) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_po.html (BITAGAP) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_ga.html (BITAGAP) http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/philobiblon/help_ca.html (BITECA) For codicological terminology, see Denis Muzerelle’s site (http://codicologia.irht.cnrs.fr ). For terminology in Portuguese, consult Maria Isabel Faria and Maria da Graça Pericão’s Dicionário do Livro. Da escrita ao livro electrónico, Coimbra: Almedina, 2008. (BITAGAP bibid 12314). Links to many databases relevant to manuscript description (bindings, codicology, paleography, ruling, watermarks, seals, etc.) appear in PhiloBiblon online, in RESOURCES. Bookmark this page in all of your browsers to facilitate quick consultation of useful resources. For the purposes of filling out this form, the term “manuscript” refers to the physical object in which a text is written, whether a book/codex or a loose piece of parchment. A manuscript might consist of hundreds of bound leaves, five gatherings, or a single sheet of paper. The term “manuscript” is used here for all of these. A factitious manuscript is comprised of several parts or sections of different provenance. It can include codicologically distinct quires (parchment and paper), leaves or gatherings copied in different eras, printed texts, etc. A separate form with a detailed description must be prepared for each part of the manuscript that contains an appropriate text for the relevant bibliography. Information for the entire manuscript is included only in the record for the first part, which has a manid. -

Download Artist's CV

Annely Juda Fine Art 23 Dering Street London W1S 1AW T +44 (0) 20 7629 7578 F +44 (0) 20 7491 2139 www.annelyjudafineart.co.uk [email protected] KATSURA FUNAKOSHI Born 1951 Selected Solo Exhibitions 2019-20 Katsura Funakoshi: A Tower in the Night Forest, Work 2011-2019, Van Doren Waxter, New York, USA 2016 The Sphinx in Myself, Mie Prefectural Art Museum, Tsu, Japan Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, France 2015-16 Museum Wiesbaden, Germany 2015 Galerie Albrecht, Berlin, Germany 2014 Claude Bernardi, Paris, France 2013 Bunkamura, Tokyo, Japan 2012 Menard Art Museum, Aichi, Japan 2011 Kami City Art Museum, Kochi, Japan Recent Sculptures and Drawings, Annely Juda Fine Art, London, UK 2010 Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Contemporary Art Museum, Kumamoto, Japan 2009 Gallery Tamura, Hiroshima, Japan 2008 Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Greenberg Van Doren Gallery, New York, USA Tokyo Metropolitan Teien Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan Ando Gallery, Tokyo, Japan 2007 Gallery Tamura, Hiroshima 2006 Cite Du Livre, Aix En Provence Nishimura Gallery, Tokyo 2005 Continental Gallery, Sapporo VAT No. GB 234 4061 93 Incorporated as Annely Juda Fine Art Ltd. Registered in England and Wales No. 2261663. Registered office as above. Annely Juda Fine Art 23 Dering Street London W1S 1AW T +44 (0) 20 7629 7578 F +44 (0) 20 7491 2139 www.annelyjudafineart.co.uk [email protected] Annely Juda Fine Art, London / Ernst Barlach Haus, Hamburg Tokyo Zokei University, ZOKEI Gallery 2004 Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo Gallery Tamura, Hiroshima Galerie Frank -

Building Other Custom Screens

Building Other Custom Screens Overview Advanced Custom Forms Overview Advanced Custom Forms provide you more control over the look and layout of the form that users will be accessing to enter data. You can access Advanced Custom Forms by expanding the Custom Form from the Custom Form main screen. Advanced Custom Forms To begin building an Advanced Custom Forms screen, click the Add Advanced Form link. The Advanced Custom Form Maintenance screen will display. Enter a Name for the screen and begin adding content to the form. We will now review one section at a time, as well as the buttons/options on the Advanced Custom Form Maintenance screen. System: This field cannot be edited. It is based on the type of Custom Form you are working in. Name: This is the name of the Advanced Custom Form and is the name that users will see when trying to access the information. Layout: Click this button to toggle the orientation of the form between Portrait (the default) or Landscape. This effects how the form will print when sent to a printer. Table: The options under here are to be used if using a table on the form. You would want your cursor placed in the row you wish to work with, and then you can select to Clone a Row, Delete a Row, or Delete to Last Row which will remove the row with your cursor, and all rows of the table below it. Fields: This is where you can access all of the available Skyward fields and Custom Fields created for the form and choose to add them to your form. -

How to Look at Japanese Art I

HOWTO LOOKAT lAPANESE ART STEPHEN ADDISS with Audrey Yos hi ko Seo lu mgBf 1 mi 1 Aim [ t ^ ' . .. J ' " " n* HOW TO LOOK AT JAPANESE ART I Stephen Addi'ss H with a chapter on gardens by H Audrey Yoshiko Seo Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers ALLSTON BRANCH LIBRARY , To Joseph Seuhert Moore Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Addiss, Stephen, 1935- How to look at Japanese art / Stephen Addiss with a chapter on Carnes gardens by Audrey Yoshiko Seo. Lee p. cm. “Ceramics, sculpture and traditional Buddhist art, secular and Zen painting, calligraphy, woodblock prints, gardens.” Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-8109-2640-7 (pbk.) 1. Art, Japanese. I. Seo, Audrey Yoshiko. II. Title N7350.A375 1996 709' .52— dc20 95-21879 Front cover: Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770), Girl Viewing Plum Blossoms at Night (see hgure 50) Back cover, from left to right, above: Ko-kutani Platter, 17th cen- tury (see hgure 7); Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875), Sencha Teapot (see hgure 46); Fudo Myoo, c. 839 (see hgure 18). Below: Ryo-gin- tei (Dragon Song Garden), Kyoto, 1964 (see hgure 63). Back- ground: Page of calligraphy from the Ishiyama-gire early 12th century (see hgure 38) On the title page: Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858), Yokkaichi (see hgure 55) Text copyright © 1996 Stephen Addiss Gardens text copyright © 1996 Audrey Yoshiko Seo Illustrations copyright © 1996 Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Published in 1996 by Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, New York All rights reserv'ed. No part of the contents of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher Printed and bound in Japan CONTENTS Acknowledgments 6 Introduction 7 Outline of Japanese Historical Periods 12 Pronunciation Guide 13 1.