Transit Universal Design Guidelines Principles and Best Practices for Implementing Universal Design in Transit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Design for All' Versus 'One-Size-Fits-All': the Case Of

‘Design for All’ versus ‘One-Size-Fits-All’: the Case of Cultural Heritage 1 2 Daniela Fogli , Alberto Arenghi 1Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell'Informazione Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] 2Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Architettura, Territorio e Ambiente e di Matematica Università degli Studi di Brescia, Brescia, Italy [email protected] Abstract. This paper would like to discuss the design trade-offs that might emerge during the development of technological solutions for promoting and enhancing the fruition of cultural heritage. To this aim, the paper briefly describes the UniBSArt4All project, which employs advanced interactive technologies, such as artwork recognition and wireless sensors, to obtain engaging and accessible visitor experiences customized to different users’ profiles. By reflecting on the project development and its preliminary results, the paper finally proposes a meta-design approach to inclusive design in the CH domain. Keywords: Cultural heritage, augmented reality, beacon, end-user development, meta-design, inclusive design, design for all 1 Introduction In our everyday life, we often encounter trade-offs, namely situations where we need to renounce to something in order to gain something else. Problem solving usually represents such a situation, in which a solution must be designed by taking into account both the goals one would like to satisfy and the different constraints that impose choosing among those goals. Therefore, usually design “is the identification, discussion and resolution of trade-offs” [15]. Indeed, as underlined by Gerhard Fischer, a design problem does not have a correct solution or a right answer, but the solution or the answer depends on the values and interests of the involved stakeholders [6][7]. -

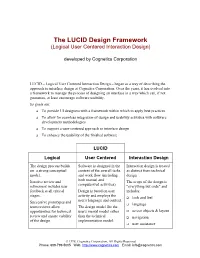

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design)

The LUCID Design Framework (Logical User Centered Interaction Design) developed by Cognetics Corporation LUCID – Logical User Centered Interaction Design – began as a way of describing the approach to interface design at Cognetics Corporation. Over the years, it has evolved into a framework to manage the process of designing an interface in a way which can, if not guarantee, at least encourage software usability. Its goals are: q To provide UI designers with a framework within which to apply best practices q To allow for seamless integration of design and usability activities with software development methodologies q To support a user-centered approach to interface design q To enhance the usability of the finished software LUCID Logical User Centered Interaction Design The design process builds Software is designed in the Interaction design is treated on a strong conceptual context of the overall tasks as distinct from technical model. and work flow (including design. both manual and Iterative review and The scope of the design is computerized activities). refinement includes user "everything but code" and feedback at all critical Design is based on user includes: stages. activity and employs the q look and feel user's language and context. Successive prototypes and q language team reviews allow The design model fits the opportunities for technical user's mental model rather q screen objects & layout review and ensure viability than the technical q navigation of the design implementation model. q user assistance © 1998, Cognetics Corporation, All Rights Reserved Phone: 609-799-5005 Web: http://www.cognetics.com Email: [email protected] An Introduction to the LUCID Framework Page 2 Over the past 30 years, several techniques for managing software development projects have been developed and documented. -

Making a Makerspace? Guidelines for Accessibility and Universal Design

Making a Makerspace? Guidelines for Accessibility and Universal Design Many engineering departments, libraries, and Student Voices universities are launching new initiatives to create Why are accessible makerspaces important, makerspaces, physical spaces where students, and how do we involve more students with faculty, and the broader community can gather disabilities? and share resources and knowledge, work on projects, network, and build. In creating these • “Makerspaces are about community. innovative spaces we should apply principles of We need to ensure everyone from the universal design to ensure the spaces, tools, and community can participate.” community are accessible to as many individuals as possible. • “Makerspaces are often used to help build new assistive technology and increase Universal design encourages the design of space, accessibility; however, many of these spaces products, and processes not just for the average and tools remain inaccessible. We need to user, but for people with a broad range of abilities, make sure disabled people can access these ages, reading levels, learning styles, languages, spaces and create the products and designs cultures, and other characteristics. Makerspaces that they actually want.” foster innovation, and we want to ensure that individuals of all backgrounds and abilities can actively contribute to the design process. We Planning and Policies advocate for participatory design (interactions. Create a culture of inclusion and universal design acm.org/archive/view/march-april-2015/design-for- as early as possible. During your planning process user-empowerment) where individuals from diverse consider the following questions: backgrounds bring their unique experiences and • Are people with a variety of disabilities in- perspectives to the design process. -

Assistive Technology That's Free

AT That’s Free By Andrew Leibs Before the digital age, assistive technology was hard to miss, and hard to buy. Classmates would see a sight-impaired student’s boxy video magnifier or hear her computer talk. These were costly, clunky solutions usually acquired through special education. Today, we have the inverse: sleek laptops, tablets, and smartphones now have so much processing power, manufacturers can enfold functionality – e.g., screen reading, magnification, audio playback – that once necessitated separate software or machines. All Windows and iOS devices have more built-in accessibility than most users will ever need or know they have. And what’s not built into the operating system is usually available as a free mobile app, web service, or downloadable application. Here’s a quick look at some of the assistive applications you either have or can quickly snag to make reading, writing, online research, and information sharing more accessible or efficient. Accessibility Built Into Microsoft Windows & Office The Microsoft Windows operating system provides three main accessibility applications: Narrator, a screen reader; Magnifier, a text and image enlarger; and On-Screen Keyboard, an input option for persons who are unable to type on a standard keyboard. The programs are located in the system’s Ease of Access Center. To get there, click Start, Control Panel, and then Ease of Access Center. The Center lets you change accessibility settings, activate built-in command tools, and fill out a questionnaire to receive personalized recommendations. • Narrator is a screen reader that lets users operate their PC without a display. Narrator reads all onscreen text aloud, provides verbal cues to navigate programs, and has keyboard shortcuts for choosing what's read, e.g., “Insert + F8” will read the current document. -

Design for All: Not Excluded by Design

A Friendly Rest Room: Developing Toilets of the Future for Disabled and Elderly People 7 J.F.M. Molenbroek et al. (Eds.) IOS Press, 2011 © 2011 The authors. All rights reserved. doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-752-9-7 Design for All: Not Excluded by Design Johan F.M. MOLENBROEKa,1, Theo J.J. GROOTHUIZENb, R. DE BRUINc a Faculty of Industrial Design – Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands b Design Consultant – Groothuizen Beheer bv, Rotterdam, The Netherlands c Erin Ergonomics and Industrial Design, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Abstract. Inclusive Design or Design for All refers to the design philosophy of including as many users groups as possible in the target population of a to-be- designed product and to be aware of the ones that are excluded. This paper explains about the history, current status and possibilities of Inclusive Design as strategy. Within the FRR-project this strategy was leading when design decisions had to be taken. The outcome is a truly Friendly Rest Room, fulfilling the needs of disabled and elderly in a non-stigmatizing manner, and thus favoured by us all. Keywords: Inclusive Design, Design for All, Universal Design 1. Introduction 1.1. The Need to Design for All In Europe and the Western world in general, the quality of life for its inhabitants has dramatically improved over the last couple of decades. The numbers of people that reach the age of 65 have been fast growing. For instance in the Netherlands 6% of the population in 1900 was aged 65+ to more than 12% in 2000 and perhaps 25% in 2050. -

Accessibility Standards Activities

INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS EFFORTS TOWARDS SAFE ACCESSIBILITY TECHNOLOGY FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES: CROSS-INDUSTRY ACTIVITIES Roger Bostelman August 24, 2010 1 of 20 1. Introduction a. US Government Accessibility Standards Activities Because of their large potential impact, accessibility standards might be thought of by many as only including the US Department of Justice Rehabilitation Act Section 508 standard or the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards. Section 508 requires that electronic and information technology that is developed by or purchased by the Federal Agencies be accessible to people with disabilities. [1] The ADA standard part 36 of 1990 (42 U.S.C. 12181), prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability by public accommodations and requires places of public accommodation and commercial facilities to be designed, constructed, and altered in compliance with the accessibility standards established by this part. [2] Other US Federal Government agencies have ADA responsibilities as listed here with the regulating agency shown in parentheses: Consider Employment (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) Public Transportation (Department of Transportation) Telephone Relay Service (Federal Communications Commission) Proposed Design Guidelines (Access Board) Education (Department of Education) Health Care (Department of Health and Human Services) Labor (Department of Labor) Housing (Department of Housing and Urban Development) Parks and Recreation (Department of the Interior) Agriculture (Department of Agriculture) Like the agencies listed, the US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) supports and complies with the 508 and ADA standards. Moreover, NIST was directed by the Help America Vote Act of 2002, to work with the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) and Technical Guidelines Development Committee (TGDC) to develop voting system standards - Voluntary Voting System Guidelines (VVSG). -

Inclusive Design for Mobile Devices with WCAG and Attentional Resources in Mind

Linköping University | Department of Computer and Information Science Master’s thesis, 30 credits | Cognitive science Spring term 2020 | ISRN: LIU-IDA/KOGVET-A--20/010--SE Inclusive Design for Mobile Devices with WCAG and Attentional Resources in Mind An investigation of the sufficiency of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines when designing inclusively and the effects of limited attentional resources. Josefin Carlbring Tutor: Erik Marsja (IBL) Examinator: Arne Jönsson (IDA) Copyright The publishers will keep this document online on the Internet – or its possible replacement – for a period of 25 years starting from the date of publication barring exceptional circumstances. The online availability of the document implies permanent permission for anyone to read, to download, or to print out single copies for his/hers own use and to use it unchanged for non-commercial research and educational purpose. Subsequent transfers of copyright cannot revoke this permission. All other uses of the document are conditional upon the consent of the copyright owner. The publisher has taken technical and administrative measures to assure authenticity, security and accessibility. According to intellectual property law the author has the right to be mentioned when his/her work is accessed as described above and to be protected against infringement. For additional information about the Linköping University Electronic Press and its procedures for publication and for assurance of document integrity, please refer to its www home page: http://www.ep.liu.se/. © Josefin Carlbring ii iii Abstract When designing for the general population it is important to design inclusively in order to invite to participation in today’s digital society. -

Disability Rights Movement —The ADA Today

COVER STORY: ADA Today The Disability Rights Movement —The ADA Today Karen Knabel Jackson navigates Washington DC’s Metro. by Katherine Shaw ADA legislation brought f you’re over 30, you probably amazing changes to the landscape—expected, understood, remember a time in the and fostering independence, access not-too-distant past when a nation, but more needs and self-suffi ciency for people curb cut was unusual, there to be done to level the with a wide range of disabilities. were no beeping sounds at playing fi elds for citizens Icrosswalks on busy city street with disabilities. Yet, with all of these advances, corners, no Braille at ATM court decisions and inconsistent machines, no handicapped- policies have eroded the inten- accessible bathroom stalls at the airport, few if tion of the ADA, lessening protections for people any ramps anywhere, and automatic doors were with disabilities. As a result, the ADA Restoration common only in grocery stores. Act of 2007 (H.R. 3195/S. 1881) was introduced last year to restore and clarify the original intent Today, thanks in large part to the Americans with of the legislation. Hearings have been held in both Disabilities Act (ADA), which was signed into law the House and Senate and the bill is expected to in 1990, these things are part of our architectural pass in 2008. 20 Momentum • Fall.2008 Here’s how the ADA works or doesn’t work for some people with MS today. Creating a A no-win situation Pat had a successful career as a nursing home admin- istrator in the Chicago area. -

Universal Design in Architectural Education: Who Is Doing It? How Is It Being Done?

Universal design in architectural education: Who is doing it? How is it being done? 1 1 1 Megan Basnak , Beth Tauke , Sue Weidemann 1IDeA Center, University at Buffalo—State University of New York, Buffalo, NY ABSTRACT: The World Health Organization estimates that over one billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, have some form of disability. As demographics change and the world’s population continues to age, this number is expected to dramatically increase. In response to this global trend, many designers, advocates, and anyone interested in making physical and visual environments more usable for people with diverse backgrounds and abilities have adopted the philosophy known as universal design (UD), inclusive design, or design for all. Despite the demonstrated need for designers who are knowledgeable in UD theory and practice, it seems that architecture programs in U.S. universities have been slow to adequately incorporate UD into their curricula. In an effort to gain a better understanding of the current state of UD content in architecture curricula, researchers distributed an online survey to architectural educators and administrators in 120 U.S. institutions with accredited degree programs. The study, sponsored by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), consisted of qualitative and quantitative questions that sought information related to the understanding, attitudes, and incorporation of UD into each participant’s curriculum. Responses were obtained from 463 participants representing 104 of the 120 surveyed schools. Quantitative analyses found relationships between perceived attitudes of administrators, faculty, and students and the effectiveness of UD components in a program. Qualitative findings were rich and complex, revealing great variability across schools, in terms of how, when (course level), and the degree to which UD aspects were incorporated into programs. -

Enhancing Accessibility for Persons with Disabilities to Conferences and Meetings of the United Nations System

JIU/REP/2018/6 ENHANCING ACCESSIBILITY FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES TO CONFERENCES AND MEETINGS OF THE UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM Prepared by Gopinathan Achamkulangare Joint Inspection Unit Geneva 2018 United Nations JIU/REP/2018/6 Original: ENGLISH ENHANCING ACCESSIBILITY FOR PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES TO CONFERENCES AND MEETINGS OF THE UNITED NATIONS SYSTEM - Prepared by Gopinathan Achamkulangare Joint Inspection Unit United Nations, Geneva 2018 iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Enhancing accessibility for persons with disabilities to conferences and meetings of the United Nations system JIU/REP/2018/6 I. Background and context About 15 per cent of the world’s population is estimated to live with some form of disability.1 In almost all societies, persons with disabilities face more barriers than those without, with regard to participation in and access to deliberative processes, and are at greater risk of being left behind. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which currently guides the developmental activities of all United Nations system organizations, is aimed at addressing these inequities through the key pledge to “leave no one behind”. Indeed, the Sustainable Development Goals reference disability in seven targets across five goals, while another six goals have targets linked to disability-inclusive development. A perspective relating to the inclusion of persons with disabilities and their rights, as outlined in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and particularly as relates to accessibility, must consequently be effectively incorporated into all facets of the work of the United Nations system organizations. Persons with disabilities should have a representative voice, chosen by persons with disabilities themselves, in every platform that has an impact on their interests, for they are best positioned to identify their own needs and the most suitable policies for meeting those needs. -

9.2 MB Fort Mcnair Design Narrative

Design Narrative 100% Design Submission FY21 - McNair Group 01 Quarters 10 - 15 USACE Project reference: JBMHH Army Family Housing Project number: 60615576 June 09, 2021 Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Quality information Prepared Checked Verified by Approved by by by Blank Blank Blank Blank Krista Joshua Ryan Krista Kehrer Levy Horner/Troy Kehrer Project Metz Manager Revision History Revision Revision Details Authorized Name Position date 0 Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Distribution List # Hard PDF Association / Company Name Copies Required Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank Blank blank Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family Housing Solicitation Number – W912DR21BXXXX Prepared for: USACE W912DR21BXXXX -W912DR19F0647 Vivian Wong 2 Hopkins Plaza Baltimore, MD 21201 Prepared by: Krista Kehrer Project Manager T: 703-682-4973 M: 703-867-7948 E: [email protected] AECOM 3101 Wilson Boulevard Arlington, VA 22201 aecom.com Copyright © 2019 by AECOM All rights reserved. No part of this copyrighted work may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of AECOM. Prepared for: USACE AECOM Design Narrative Project reference: JBMHH Family -

What Is Universal Design…Inclusive Design…Design-For-All?

What is universal design…inclusive design…design-for-all? …a framework for the design of places, things, information, communication and policy that focuses on the user, on the widest range of people operating in the widest range of situations without special or separate design. Or, more simply: Human-Centered design (of everything) with everyone in mind Universal Design Principles: Equitable Use: The design does not disadvantage or stigmatize any group of users. Flexibility in Use: The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. Simple, Intuitive Use: Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. Perceptible Information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. Tolerance for Error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. Low Physical Effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably, and with a minimum of fatigue. Size and Space for Approach & Use: Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use, regardless of the user’s body size, posture, or mobility. [Developed by a group of US designers and design educators from five organizations in 1997. Principles are copyrighted to the Center for Universal Design, School of Design, State University of North Carolina at Raleigh. The Principles are in use internationally.] Relationship between Legally Mandated Accessibility & Inclusive Design Legally mandated requirements for accessible design, within a civil or human rights context, provide a vital basis for autonomy and equal opportunity for people with disabilities.