Download Essay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area

Crashing waves, redwoods and historic sites Discover California State Parks in the Monterey Area Some of the most beautiful sights in California can be found in Monterey area California State Parks. Rocky cliffs, crashing waves, redwood trees, and historic sites are within an easy drive of each other. "When you look at the diversity of state parks within the Monterey District area, you begin to realize that there is something for everyone - recreational activities, scenic beauty, natural and cultural history sites, and educational programs,” said Dave Schaechtele, State Parks Monterey District Public Information Officer. “There are great places to have fun with families and friends, and peaceful and inspirational settings that are sure to bring out the poet, writer, photographer, or artist in you. Some people return to their favorite state parks, year-after-year, while others venture out and discover some new and wonderful places that are then added to their 'favorites' list." State Parks in the area include: Limekiln State Park, 54 miles south of Carmel off Highway One and two miles south of the town of Lucia, features vistas of the Big Sur coast, redwoods, and the remains of historic limekilns. The Rockland Lime and Lumber Company built these rock and steel furnaces in 1887 to cook the limestone mined from the canyon walls. The 711-acre park allows visitors an opportunity to enjoy the atmosphere of Big Sur’s southern coast. The park has the only safe access to the shoreline along this section of cast. For reservations at the park’s 36 campsites, call ReserveAmerica at (800) 444- PARK (7275). -

Federal Register/Vol. 71, No. 110/Thursday, June 8, 2006/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 71, No. 110 / Thursday, June 8, 2006 / Rules and Regulations 33239 request for an extension beyond the Background Background on Viticultural Areas maximum duration of the initial 12- The final regulations (TD 9254) that TTB Authority month program must be submitted are the subject of this correction are electronically in the Department of under section 1502 of the Internal Section 105(e) of the Federal Alcohol Homeland Security’s Student and Revenue Code. Administration Act (the FAA Act, 27 Exchange Visitor Information System U.S.C. 201 et seq.) requires that alcohol (SEVIS). Supporting documentation Need for Correction beverage labels provide consumers with must be submitted to the Department on As published, final regulations (TD adequate information regarding product the sponsor’s organizational letterhead 9254) contains an error that may prove identity and prohibits the use of and contain the following information: to be misleading and is in need of misleading information on such labels. (1) Au pair’s name, SEVIS clarification. The FAA Act also authorizes the identification number, date of birth, the Secretary of the Treasury to issue length of the extension period being Correction of Publication regulations to carry out its provisions. requested; Accordingly, the final regulations (TD The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and (2) Verification that the au pair 9254) which was the subject of FR Doc. Trade Bureau (TTB) administers these completed the educational requirements 06–2411, is corrected as follows: regulations. of the initial program; and On page 13009, column 2, in the Part 4 of the TTB regulations (27 CFR (3) Payment of the required non- preamble, under the paragraph heading part 4) allows the establishment of refundable fee (see 22 CFR 62.90) via ‘‘Special Analyses’’, line 4 from the definitive viticultural areas and the use Pay.gov. -

City of Watsonville Historic Context Statement (2007)

Historic Context Statement for the City of Watsonville FINAL REPORT Watsonville, California April 2007 Prepared by One Sutter Street Suite 910 San Francisco CA 94104 415.362.7711 ph 415.391.9647 fx Acknowledgements The Historic Context Statement for the City of Watsonville would not have been possible without the coordinated efforts of the City of Watsonville Associate Planner Suzi Aratin, and local historians and volunteers Ann Jenkins and Jane Borg whose vast knowledge and appreciation of Watsonville is paramount. Their work was tireless and dependable, and their company more than pleasant. In addition to hours of research, fact checking and editing their joint effort has become a model for other communities developing a historic context statement. We would like to thank the City of Watsonville Council members and Planning Commission members for supporting the Historic Context Statement project. It is a testimony to their appreciation and protection of local history. Thanks to all of you. Table of Contents Chapter Page 1.0 Background and Objectives 1 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Location and Boundaries of Study 1.3 Context Statement Objective 2.0 Methodology 5 2.1 Context Statement Methodology 2.2 Summary of Resources 3.0 Introduction to Historic Contexts 7 3.1 Summary of Historic Contexts 3.2 Summary of Regional History Before Incorporation 3.3 Summary of regional history from 1868 – 1960 4.0 Historic Context 1 - Municipal Development 17 4.1 Overview 4.2 History 4.2.1 Schools 4.2.2 Civic Institutions 4.2.3 Infrastructure: Water 4.2.4 Infrastructure: -

Monterey Bay Chapter Archive of Field Trips 2016

22-Oct-19 California Native Plant Society – Monterey Bay Chapter Archive of Field Trips 2016- Table of Contents 2019 ............................................................................................................................................................ 11 Sunday, December 29 ......................................................................................................................... 11 Williams Canyon Hike to Mitteldorf Preserve................................................................................. 11 Saturday, December 21....................................................................................................................... 11 Fly Agaric Mushroom Search .......................................................................................................... 11 Saturday, December 7......................................................................................................................... 11 Buzzards Roost Hike, Pfeiffer State Park ......................................................................................... 11 Saturday, November 23 ...................................................................................................................... 11 Autumn in Garzas Creek, Garland Ranch ........................................................................................ 11 Wednesday, November 13 ................................................................................................................. 11 Birds and Plants of Mudhen Lake, Fort -

Explore Monterey County

Old Fisherman’s Wharf Post Ranch Inn, Big Sur Monterey County boasts 99 miles of coastline and 3,771 square miles of magnificence that begs for exploration. From submarine depths to elevations of over 5,500 feet, Monterey County invites you to grab life by the moments and discover an unlimited array Explore of things to see and do. Plan your next trip and explore more with Monterey our interactive map at SeeMonterey.com. County White-sand beach at Carmel-by-the-Sea Paragliding at Marina State Beach DESTINATION GUIDE AND MAP Carmel-by-the-Sea Monterey Big Sur Marina UNFORGETTABLE CHARM BOUNTY ON THE BAY SCENERY BEYOND COMPARE ADVENTURE ON LAND, SEA & AIR The perfect itinerary of California’s Central Coast isn’t Monterey’s never-ending activities and various attractions will With its breathtaking beauty and unparalleled scenery, Big Sur Marina is wonderfully diverse, teeming with options for food, complete without a visit to picturesque Carmel-by-the-Sea. keep you busy from the moment you wake until you rest your beckons for you to explore. Rocky cliffs, lush mountains, coastal culture, and adventure. On top of the bay, its scenic trails and This quaint town is a delightful fusion of art galleries, boutiques, head at night. Its robust and remarkable history has attracted redwood forests, and hidden beaches combine to create an epic seascapes afford endless possibilities for fun and exploration, charming hotels, a white-sand beach, diverse restaurants, and visitors since the 1700s. Today, the abundance of restaurants, backdrop for recreation, romance, and relaxed exploration. attracting bicyclists, hang gliders, paragliders, kite enthusiasts, whimsically styled architecture. -

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan

Big Sur Sustainable Tourism Destination Stewardship Plan DRAFT FOR REVIEW ONLY June 2020 Prepared by: Beyond Green Travel Table of Contents Acknowledgements............................................................................................. 3 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 About Beyond Green Travel ................................................................................ 9 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 10 Vision and Methodology ................................................................................... 16 History of Tourism in Big Sur ............................................................................. 18 Big Sur Plans: A Legacy to Build On ................................................................... 25 Big Sur Stakeholder Concerns and Survey Results .............................................. 37 The Path Forward: DSP Recommendations ....................................................... 46 Funding the Recommendations ........................................................................ 48 Highway 1 Visitor Traffic Management .............................................................. 56 Rethinking the Big Sur Visitor Attraction Experience ......................................... 59 Where are the Restrooms? -

Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin, Forebay Aquifer Subbasin • Groundwater Basin Number: 3-4.04 • County: Monterey • Surface Area: 94,000 Acres (147 Square Miles)

Central Coast Hydrologic Region California’s Groundwater Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin Bulletin 118 Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin, Forebay Aquifer Subbasin • Groundwater Basin Number: 3-4.04 • County: Monterey • Surface Area: 94,000 acres (147 square miles) Basin Boundaries and Hydrology The Salinas Valley Groundwater Basin – Forebay Aquifer Subbasin occupies the central portion of the Salinas Valley and extends from the town of Gonzales in the north to approximately three miles south of Greenfield. The subbasin is bounded to the west by the contact of Quaternary terrace deposits of the subbasin with Mesozoic metamorphic rocks (Sur Series) or middle Miocene marine sedimentary rocks (Monterey Shale) of the Sierra de Salinas. To the east, the boundary is the contact of Quaternary terrace deposits or alluvium with granitic rocks of the Gabilan Range. The northern subbasin boundary is shared with the Salinas Valley –180/400-Foot Aquifer and –Eastside Aquifer and represents the southern limit of confining conditions in the 180/400-Foot Aquifer Subbasin. The southern boundary is shared with the Salinas Valley – Upper Valley Aquifer Subbasin and generally represents the southern limit of confining conditions above the 400-Foot Aquifer (MW 1994). This boundary also represents a constriction of the Valley floor caused by encroachment from the west by the composite alluvial fan of Arroyo Seco and Monroe Creek. Intermittent streams such as Stonewall and Chalone Creeks drain the western slopes of the Gabilan Range and flow westward across the subbasin toward the Salinas River. The major tributary drainage to the Salinas River in the Salinas Valley is Arroyo Seco, which drains a large portion of the Sierra de Salinas west of Greenfield. -

Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY California State Parks (CSP) has prepared this General Plan and Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the Carmel Area State Parks (CASP) to cover four separate park units located in Monterey County just south of the City of Carmel-by-the-Sea: two classified units of the State Park System - Point Lobos State Natural Reserve (Reserve) and Carmel River State Beach (State Beach, and two unclassified properties - Point Lobos Ranch Property (Point Lobos Ranch) and Hatton Canyon Property (Hatton Canyon). T he park lands were acquired at different times Existing Proposed Park and for different purposes beginning in 1933 with the Reserve Units/Properties Units west of State Route (SR) 1. Acquisition of Carmel River State Point Lobos State Point Lobos State Beach began in 1953. The eastern parcel of the Reserve was Natural Reserve Natural Reserve added in 1962. Other parcels were soon added to the Reserve Carmel River State New State Park - north of Point Lobos and to the State Beach at Odello Farm. A Beach Coastal Area General Plan was adopted in 1979 for the Reserve and State Point Lobos Ranch New State Park - Beach. Point Lobos Ranch was later acquired by CSP in 1998 and Property Inland Area Hatton Canyon was deeded to CSP from the California Hatton Canyon New State Park - Department of Transportation (Caltrans) in 2001. This General Property Hatton Canyon Area Plan will supersede and replace the 1979 General Plan for the Reserve and State Beach, and include a new general plan for Point Lobos Ranch and Hatton Canyon. -

Appeal Staff Report: Substantial Issue Determination

STATE OF CALIFORNIA- THE RESOURCES AGENCY CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION ciNTRAL COAST DISTRICT OFFICE '725 FRONT STREET, SUITE 300 RUZ. CA 95060 F5a { ...:863 • Filed: 11129/99 RECORD PACKET COPY 49th Day: 1117/2000 Opened & Continued: 1/12/2000 Staff: RH/CKC-SC Staff Report: 5/24/2000 Hearing Date: 6/16/2000 Commission Action: APPEAL STAFF REPORT: SUBSTANTIAL ISSUE DETERMINATION APPEAL NUMBER: A-3-MC0-99-092 LOCAL GOVERNMENT: MONTEREY COUNTY DECISION: Approved with conditions, 11 /09/99 APPLICANT: Rancho Chiquita Associates, Attn: Ted Richter APPELLANTS: Big Sur Land Trust, Attn: Zad Leavy; Department of Parks and Rec., Attn Kenneth L. Gray; and Responsible Consumers of Monterey Peninsula, Attn David Dillworth PROJECT LOCATION:· Highway One and Riley Ranch Road, across from Point Lobos State Reserve; Carmel Highlands (Monterey County) APN • 243-112-015 (see Exhibit A). PROJECT DESCRIPTION: Convert an existing single family dwelling, bam and cottage to a 10-unit bed and breakfast (see Exhibit B) FILE DOCUMENTS: Monterey County Certified Local Coastal Program, consisting of Carmel Area Land Use Plan and relevant sections of Monterey County Coastal Implementation Plan; Administrative Record for County Permit PLN970284; information on Point Lobos Ranch plans for development and subsequent acquisition by Big Sur Land Trust; County permit SB94001 for Whisler subdivision. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Staff recommends that the Commission determine that a substantial issue exists with respect to some of the grounds on which the appeal has been filed, because the coastal permit approved by Monterey County does not fully conform to the provisions of its certified Local Coastal Program. Staff recommends that the de novo hearing on the coastal permit be held at a subsequent meeting. -

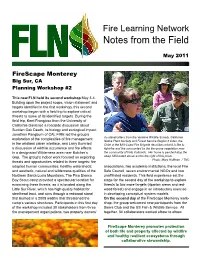

Notes from the Field

Fire Learning Network Notes from the Field May 2011 FireScape Monterey Big Sur, CA Planning Workshop #2 This new FLN held its second workshop May 3-4. Building upon the project scope, vision statement and targets identified in the first workshop, this second workshop began with a field trip to explore critical threats to some of its identified targets. During the field trip, Kerri Frangioso from the University of California-Davis led a roadside discussion about Sudden Oak Death, its biology and ecological impact. Jonathan Pangburn of CAL FIRE led the group’s As stakeholders from the Ventana Wildlife Society, California exploration of the complexities of fire management Native Plant Sociiety and Forest Service Region 5 listen, the in the wildland urban interface, and Larry Born led Chief of the Mid-Coast Fire Brigade describes what it is like to a discussion of wildfire occurrence and fire effects fight fire and live surrounded by the fire-prone vegetation near in a designated Wilderness area near Botcher’s the community of Palo Colorado. Her home is perched atop the Gap. The group’s indoor work focused on exploring steep hill located above and to the right of this photo. Photo: Mary Huffman / TNC threats and opportunities related to three targets: fire adapted human communities; healthy watersheds; associations, two academic institutions, the local Fire and aesthetic, natural and wilderness qualities of the Safe Council, seven environmental NGOs and two Northern Santa Lucia Mountains. The Pico Blanco unaffiliated residents. This field experience set the Boy Scout camp provided a spectacular location for stage for the second day of the workshop to explore examining these threats, as it is located along the threats to two more targets (riparian areas and red- Little Sur River, which has high quality habitat for wood forest) and engage in an introductory exercise steelhead trout, and runs through a redwood stand in developing conceptual system models. -

Beat Poetry 06/21/01

Big Sur COllllllunlty Llllks http://www.bigsurcalifornia.org/community.htm Landeis-Hill Big Creek Reserve and the Big Creek Marine Ecological Reserve Pacific Valley School 30f4 1211912001 11:50AM Big Sur Community Links http://www.bigsurcalifornia.org/community.htm amazon.com ~ _~- ,"""",,,,h--_<>==""X Click here to purchase books about Big Sur Big Sur Chamber of Commerce http://www.bigsurcalifornia.org (831) 667-2100 Big Sur Internet. www.bigsurinternet.com 40f4 12119/2001 11:50 AM • 11 Big Sur California Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurcalifornia.org/events.html Lodging Camping Calendar Restaurants Beaches Condors Big Sur Information Guide Calendar of Events Contact Us January I February I March IApril IMi!.Y I June 1,i.1!JY IAugust I September IOctober I November I December If you missed the Halloween Bal Masque at Nepenthe this year, have a look-see at all the beautiful costumes. Photos supplied by Central Coast Magazine. Click Here Now! JANUARY 2002 Retum to top 1 of 11 12/191200111:47 AM 1~lg Sur C'al ilornia Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurcalifornia.org/events.htm FEBRUARY 2002 Return to top MARCH 2002 Return to top 2 of 11 12/19/2001 11:47 AM Big Sur Cal ifornia Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurcalifomia.org/events.htm: APRIL 2002 Return to top MAY 2002 3 of 11 12/19/2001 11:47 AM Big Sur California Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurcalifomia.org/events.html Retum to top 4 of II 12/19/2001 11:47 AM Big Sur California Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurcalifornia.org/events.htm JUNE 2002 Return to top 5 of II 12/19/2001 11:47 AM BIg Sur Calltornia Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurealifornia.org/events.html JULY 2002 Return to top AUGUST 2002 6 of 11 12/19/2001 11:47 AM Big Sur California Calendar of Events http://www.bigsurealifornia.org/eYents.htm. -

Pancho Rico Formation Salinas Valley, California

Pancho Rico Formation Salinas Valley, California G E 0 L 0 G I CAL SURVEY P R 0 FE S S I 0 N A L PAPER 524-A Pancho Rico Formation Salinas Valley, California By DAVID L. DURHAM and WARREN 0. ADDICOTT SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 524-A A study of stratigraphy and paleontology of Pliocene marine strata in southern Salinas Vallry, California UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1965 SHORTER CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY PANCHO RICO FORMATION, SALINAS VALLEY, CALIFORNIA By DAVID L. DuRHAM and WARREN 0. AnniCOTT ABSTRACT northwestern part of the area are of a northern, cool-water type and may indicate interchange with Pliocene faunas to the north The Pancho Rico Formation of Pliocene age comprises sandy through a northwest-trending marine trough. marine strata and interbedded finer grainr.d rocks. It generally overlies the marine Monterey Shale of Miocene age and under INTRODUCTION lies the nonmarine Paso Robles Formation of Pliocene and fleistocene( ?) age in southern Monterey County, Calif. Lo Sandy marine strata succeed mudstone, porcelanite, ~ally it lies on the basement complex or on the Santa Mar and chert beds of the Monterey Shale at most places in galita Formation of upper Miocene age. It crops otrt from north the Salinas Valley, southern Monterey County, Calif. of King City southeastward for more than 50 miles to beyond the Nacimiento River and Vineyard Canyon. The Pancho Rico These sandy strata, together with interspersed finer contains sandstone, mudstone, porcelaneous mudstone, por grained rocks, constitute the Paneho Rico Formation celanite, diatomaceous mudstone, and conglomerate.