Engineering Physics I & Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineering Physics

COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Engineering Physics WHY ENGINEERING PHYSICS? graduates have gone on to become the CEO Engineering is about the way things work. of Eastman Kodak Co., work as acoustical Physics is about why things work the way engineers for Disney, work for the CIA, thrive they do. By combining the two, engineering in the financial sector, work in nuclear physics students are able to satisfy their engineering at Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant, curiosity and ultimately gain a deeper manage the power flow for northern New understanding of the engineering problems England, work as radiation physicists at medical centers, and become high-level UM aine’s ADVANTAGE they are working to solve. executives at SanDisk and Avis. • Professors with Ph.D. degrees, not graduate WHY STUDY ENGINEERING PHYSICS AT UMAINE? RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES students, teach classes UMaine engineering physics was the first UMaine engineering physics students are able • State-of-the-art teaching and accredited engineering physics program in to take advantage of a myriad of research research facilities the world. Currently, it is one of only 20 programs in the U.S. and the only opportunities as undergraduates — some as • Small, student-centered accredited one in New England. e early as their freshman year. Many work classes Department of Physics and Astronomy in closely with scientists in UMaine’s Laboratory for Surface Science and Technology, which is • Opportunities to do conjunction with the College of Engineering undergraduate research offers bachelor’s and master’s degrees in internationally known for cutting-edge alongside faculty engineering physics. e curriculum research with sensors. -

B.Sc. Mechatronics Specialization: Photonic Engineering

Study plan for: B.Sc. Mechatronics Specialization: Photonic Engineering Faculty of Mechatronics Study plan for reference only; may be subject to change. Semester 1 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 Patents and Intelectual Property 30 2 Optics and Photonics Applications 30 15 3 Calculus I 30 45 7 Algebra and Geometry 15 30 4 Engineering Graphics 15 30 2 Materials 30 2 Computer Science I 30 30 6 Engineering Physics 30 30 4 Total ECTS 30 Semester 2 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 Economics 30 2 Elective Lecture 1/Virtual and 30 3 Augmented Reality Calculus II 30 30 5 Engineering Graphics ‐ CAD 30 2 Computer Science II 15 15 5 Mechanics I i II 45 45 6 Mechanics of Structures I 30 15 4 Electric Circuits I 30 15 3 Total ECTS 30 1 Study Plan for B.Sc. Mechatronics (Spec. Photonic Engineering) Semester 3 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 0 Foreign Language 60 4 Elective Lecture 2/Introduction to 30 3 MEMS Calculus III 15 30 6 Mechanics of Structures II 15 15 4 Manufacturing Technology I 30 4 Fine Machine Design I 15 30 3 Electric Circuits II 30 3 Basics of Automation and Control I 30 15 4 Total ECTS 31 Semester 4 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 Foreign Language 60 4 Elective Lecture 3/Photographic 30 3 techniques in image acqusition Elective Lecture 4 30 3 /Enterpreneurship Optomechatronics 30 30 5 Electronics I 15 15 2 Electronics II 15 1 Fine Machine Design II 15 15 3 Manufacturing Technology 30 2 Metrology 30 30 4 Total ECTS 27 Semester 5 Course Lecture Tutorial Labs Pojects ECTS (hours) (hours) (hours) (hours) Physical Education and Sports 30 0 Foreign Language 60 4 Marketing 30 2 Elective Lecture 5/ Electric 30 2 2 Study Plan for B.Sc. -

Engineering Physics I Syllabus COURSE IDENTIFICATION Course

Engineering Physics I Syllabus COURSE IDENTIFICATION Course Prefix/Number PHYS 104 Course Title Engineering Physics I Division Applied Science Division Program Physics Credit Hours 4 credit hours Revision Date Fall 2010 Assessment Goal per Outcome(s) 70% INSTRUCTION CLASSIFICATION Academic COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is the first semester of a calculus-based physics course primarily intended for engineering and science majors. Course work includes studying forces and motion, and the properties of matter and heat. Topics will include motion in one, two, and three dimensions, mechanical equilibrium, momentum, energy, rotational motion and dynamics, periodic motion, and conservation laws. The laboratory (taken concurrently) presents exercises that are designed to reinforce the concepts presented and discussed during the lectures. PREREQUISITES AND/OR CO-RECQUISITES MATH 150 Analytic Geometry and Calculus I The engineering student should also be proficient in algebra and trigonometry. Concurrent with Phys. 140 Engineering Physics I Laboratory COURSE TEXT *The official list of textbooks and materials for this course are found on Inside NC. • COLLEGE PHYSICS, 2nd Ed. By Giambattista, Richardson, and Richardson, McGraw-Hill, 2007. • Additionally, the student must have a scientific calculator with trigonometric functions. COURSE OUTCOMES • To understand and be able to apply the principles of classical Newtonian mechanics. • To effectively communicate classical mechanics concepts and solutions to problems, both in written English and through mathematics. • To be able to apply critical thinking and problem solving skills in the application of classical mechanics. To demonstrate successfully accomplishing the course outcomes, the student should be able to: 1) Demonstrate knowledge of physical concepts by their application in problem solving. -

Tennis Court Cleaner

Robotics Overview: The purpose of this session is to learn some basics about autonomous robots. What is a robot? A robot is a specialized kind of intelligent agent. Intelligent agents represent any kind of active decision-making behavior based on achieving some goal. Robots usually mean intelligent agents that are specifically designed to sense and adjust the “real world.” A good example of an intelligent agent that is not a robot would be a smart “physicians assistant” which helps diagnose patients and keeps track of multiple drug interactions. A good example of an intelligent agent that is a robot is the Martian explorer Opportunity. Figure 1: How robots, a type of intelligent agent, typically interact with the world. Figure 1 shows how most robots are designed to interact with the world, known as the feedback control loop. The field of robotics spans many disciplines essentially because of this diagram: sensors and actuators are built using knowledge of chemistry, physics, engineering, medicine and biology. Controls are built using knowledge of computer science, mathematics, and psychology. We will mostly worry about control, or the mind here. A primitive way to implement the idea of memory is to use a state machine. If you think about how you think (a subject of psychology and artificial intelligence) your mind often has these states: when hungry seek pizza, when sleepy seek bedroom, when board call friends, etc. A state diagram formalizes this kind of state-of-mind kind of thinking which helps to design robots to behave “intelligently.” State diagrams can have many states and ways to transition from one state to another. -

Engineering Physics Dept: Engineering and Physics Major: Electrical Engineering College: Mathematics and Science Degree: Master of Science (M.S.) Major Code: 6633

University of Central Oklahoma Graduate Catalog 2021-2022 Program: Engineering Physics Dept: Engineering and Physics Major: Electrical Engineering College: Mathematics and Science Degree: Master of Science (M.S.) Major Code: 6633 Engineering Physics - Electrical Engineering, M.S. This major is designed so that its graduates can enter industry/government as practicing engineers or pursue research and teaching careers with government and/or academic institutions. The major also provides advanced study in electrical engineering, with emphasis in communications and signal processing, for students who intend to pursue a Ph.D. degree in Electrical Engineering or related fields. Graduate Advisor: Dr. Yuhao Jiang Graduate Studies. Email: [email protected] Students applying for a Master Degree through the Accelerated Office: STEM 242 BS/MS Degree Program must submit the following items to the Phone: 405 - 974 - 5472 Engineering Physics Department Accelerated Program Admissions Committee: Admission Requirements • Application for admission received by March 5 in the spring semester of the junior year. Submit the following items to: • Official copies of transcripts from each institution attended. Jackson College of Graduate Studies Transcripts must show: 100 N. University Drive, NUC 404 ◦ The applicant is a UCO Electrical Engineering major; Edmond, OK 73034 ◦ A minimum overall GPA of 3.00; • Online application for admission (www.uco.edu/graduate/). ◦ A minimum GPA of 3.00 in all Engineering and Physics • Official copies of undergraduate and graduate transcripts from courses specified in the junior year for their major. Grades each institution attended with all degrees posted. All transcripts for engineering courses taken in the spring semester of the must be from accredited institutions. -

2008 NSF-Sponsored Report: the Future of Materials Science And

THE FUTURE OF MATERIALS SCIENCE AND MATERIALS ENGINEERING EDUCATION A report from the Workshop on Materials Science and Materials Engineering Education sponsored by the National Science Foundation September 18-19, 2008 in Arlington, VA TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary . 5. Summary of the Recommendations . 9. Public Education and Outreach Recommendations . 9. Kindergarten through 12th Grade (K-12) Education Recommendations . 9. Undergraduate Education Recommendations . 10. Graduate Education Recommendations . 10. 1. Public Education and Outreach . 13. 1 .1 Introduction . 13. 1 .2 What Does the Public Know? . 13. 1 .3 What Should the Public Know? . 14. 1 .4 How Does the Public Learn About Materials Science and Materials Engineering? . 17. 1 5. How Can the Materials Community Promote Learning Using Informal Science Education? . 20. 1 .6 What is the Impact of Outreach Activities on the Career Development of Faculty? . 21. 1 .7 Recommendations . 22. 2. Kindergarten Through 12th Grade (K-12) Education . 23. 2 .1 Introduction . 23. 2 .2 Materials Education Standards and Curricula for K-12 Students . 24. 2 .3 Professional Development of K-12 Teachers . 27. 2 .4 Career Awareness for K-12 Students . 28. 2 .5 Recommendations . 29. 3. Undergraduate Education . 31. 3 .1 Introduction . 31. 3 .2 Curriculum Development . 32. 3 .3 Recruiting and Retaining Students in MSME . 34. 3 .4 Recommendations . 35. 4. Graduate Education . 37. 4 .1 Introduction . 37. 4 .2 Course Curriculum . 39. 4 .3 Interdisciplinary Training . 41. 4 .4 Career Preparation . 43. 4 .5 Recommendations . 44. 5. Cross-Cutting Theme: Use of Information Technology in MSME Education and Research . 45. 6. Workshop Program . 47. 7. -

Engineering Physics a Guide for Undergraduate Majors

Engineering Physics A Guide for Undergraduate Majors Last modified Fall 2015 This guide applies to students entering the program after August 2015. Students admitted prior to this should continue to follow the Undergraduate Student guide in effect when they entered the program. They may petition the department to select features of the new curriculum. Administered by the Department of Engineering Physics 153 Engineering Research Building, 1500 Engineering Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1609 Phone: (608) 263-1646, Fax: (608) 263-7451, Internet: www.engr.wisc.edu/ep/ Introduction The Engineering Physics Undergraduate Program (EP) is administered by the Department of Engineering Physics. The Department Office is room 153 Engineering Research Building (ERB). The Department Chair’s office is also in room 153 ERB. The department also administers the Engineering Mechanics undergraduate and graduate programs (EM) as well as the Nuclear Engineering undergraduate (NE) and the Nuclear Engineering and Engineering Physics graduate programs (NEEP). This guide is intended to provide Engineering Physics undergraduate students with information that will facilitate their studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In addition to this guide, you should consult the Undergraduate Catalog (www.pubs.wisc.edu/ug/engr_engphys.htm) for requirements, objectives, and course descriptions. You may also find the resources page at the UW website helpful https://www.admissions.wisc.edu/ The Engineering Physics Department web site is www.engr.wisc.edu/ep.html. There are links to the Engineering Physics, Engineering Mechanics, and Nuclear Engineering programs. Updated curriculum and course information is included on the department website. The College of Engineering website (www.engr.wisc.edu/ep.html) also provides information for engineering students. -

Curriculum for Engineering Physics with Concentration in Electrical and Computer Engineering

CURRICULUM FOR ENGINEERING PHYSICS WITH CONCENTRATION IN ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING (126-128 Credits) PROFESSIONAL ORIENTATION (1 Cr. Required) Selected from the following Introduction to AE & ME AENG/MENG 1001 1 Biomedical Engineering Orientation BME 1000 1 Introduction to ECE ECE 1001 1 Introduction to Physics PHYS 1110 1 BASIC SCIENCE & MATHEMATICS (46 Cr.) (ABET Minimum = 32 Cr.) General Chemistry I/Lab CHEM 1110/1115 4 Calculus I MATH 1510 4 Calculus II MATH 1520 4 Calculus III MATH 2530 4 Differential Equations I MATH 3550 3 Advanced Mathematics for Engineers MATH 3270 3 Numerical Analysis MATH 3240 3 Foundations of Statistics MATH 3850 3 Engineering Physics I/Lab PHYS 1610/1620 4 Engineering Physics II/Lab PHYS 1630/1640 4 Modern Physics/Lab PHYS 2610/2620 4 Classical Mechanics PHYS 3110 3 Quantum Mechanics PHYS 4610 _3 46 ENGINEERING PHYSICS & ENGINEERING TOPICS (50-51 Cr.) (ABET Minimum = 48 Cr.) Intro. to CS: Scientific Programming CSCI 1060 3 Engineering Circuits I ECE 2101 3 Engineering Circuits II ECE 2102 3 Electrical Science Lab ECE 2103 1 Semiconductor Devices ECE 3130 3 Electromagnetic Fields ECE 3140 3 ECE Design I, II (Senior Project) ECE 4800, 4810 6 Optics/Lab PHYS 3310/3320 4 Thermodynamics & Statistical Mechanics PHYS 3410 3 2 Engineering Physics Electives PHYS 4XXX _6 35 Track 1 Electromagnetic Fields and Waves Electric Energy Conversion ECE 3110 3 Communication Systems ECE 4160 3 Electromagnetic Waves ECE 4140 3 2 Engineering Electives Selected in consultation with advisor 6 15 Track 2 Analog Electronics Linear Systems -

Engineering Physics 1

Engineering Physics 1 PHYS 1020 (4) Physics of Everyday Life 2 ENGINEERING PHYSICS Intended primarily for nonscientists, this course is a continuation of PHYS 1010. Includes electrical power generation and distribution, Engineering physics provides students with a broad exposure to the basic electrical motors, radio, television, computers, copiers, lasers, fluorescent physical theories and mathematical techniques underlying engineering. lights, cameras, and medical imaging. Department enforced prereq., high The program may be specialized to meet the student's interests through school algebra. engineering electives. Most students become involved in laboratory Requisites: Requires prerequisite course of PHYS 1010 (minimum grade research, and graduates find opportunities in optics, electronics, C-). magnetics, and other hardware-based job markets. The program also Additional Information: GT Pathways: GT-SC1 - Natural Physcal Sci:Lec provides excellent preparation for graduate study in physics, applied Crse w/ Req Lab physics, and other areas of the natural sciences and engineering. Arts Sci Core Curr: Quant Reasn Mathmat Skills Arts Sci Core Curr: Natural Science Sequence The engineering physics program focuses on the foundations of Arts Sci Core Curr: Natural Science Lab modern technology. The program prepares students for research, Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Natural Sciences development, and entrepreneurial careers in many frontier areas of Arts Sci Gen Ed: Quantitative Reasoning Math engineering, including quantum devices, ultra fast lasers, adaptive optics, Arts Sci Gen Ed: Distribution-Natural Sci Lab cryogenic electronics, computer simulation of physical systems, solar cells, magnetic storage technology, micro-mechanical systems, and PHYS 1110 (4) General Physics 1 molecular electronics. All students study the core theoretical subjects Three lect., one rec. -

Engineering Physics Advising Guide

Undergraduate Advising Guide Academic Year 2019-2020 Duane Physics, E1B32 390 UCB Boulder, CO 80309-0390 www.colorado.edu/physics Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Engineering Physics Mission Statement ....................................................................................................... 1 Engineering Physics Overview ...................................................................................................................... 1 Employment Opportunities for Engineering Physics Graduates .................................................................. 2 Engineering Physics Curriculum .................................................................................................................... 2 Academic Advising Policy .............................................................................................................................. 3 Advising Required Every Semester ........................................................................................................... 3 Student E-mail Policy ................................................................................................................................ 3 Questions .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Additional Advising Resources ..................................................................................................................... -

BS in Electrical Engineering & Physics (Dual Degree) Academic Plan of Study

B.S. in Electrical Engineering & Physics (dual degree) Academic Plan of Study William States Lee College of Engineering + College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Dept. of Electrical and Computer Engineering + Dept. of Physics & Optical Science ece.uncc.edu & physics.uncc.edu PROGRAM SUMMARY • Credit Hours: 133 hours • Concentrations: No • Declaring the Major: Students should declare a dual degree in Physics and Engineering by their sophomore or junior year. • Advising (For the Major): (Engineering) Ms. Jerena McNeil, [email protected] or another Engineering advisor; (Physics) Dr. Tom Suleski, [email protected] • Advising (For General Education): Engineering Advisor • Minimum Grades/GPA: Students must have a 2.0 or higher average in Physics courses to graduate. A “C” or better is required in most PHYS classes before students can progress to the next PHYS course. Students must have a 2.0 overall GPA as well as in engineering courses. • Teacher Licensure: No • Evening Classes Available: Some but need to take day classes to complete requirements. • Weekend Classes Available: No • Other Information: College Internships, Co-ops, Leadership Academy, Freshmen Learning Community. • Contact(s): (Engineering) Ms. Jerena McNeil Undergraduate Student Services Specialist ([email protected], 704-687-8445, EPIC 2242); (Physics) Dr. Tom Suleski, [email protected] PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS To obtain a dual B.S. degree in Electrical Engineering and Physics, an undergraduate student must complete all requirements for the B.S.E.E. degree as established by the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. In addition, the student must complete 12 hours of upper division physics courses specified by the Department of Physics and Optical Science with an average grade of C or above. -

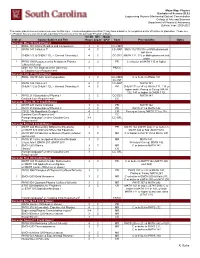

2020 Physics-Engineering Physics (Mechanical Option) Major

Major Map: Physics Bachelor of Science (B.S.) Engineering Physics (Mechanical Option) Concentration College of Arts and Sciences Department of Physics & Astronomy Bulletin Year: 2020-2021 This course plan is a recommended sequence for this major. Courses designated as critical (!) may have a deadline for completion and/or affect time to graduation. Please see the Program Notes section for details regarding “critical courses” for this particular Program of Study. Credit Min. Major Critical Course Subject and Title Hours Grade1 GPA2 Code Prerequisites Notes Semester One (16 Credit Hours) ! ENGL 101 Critical Reading and Composition 3 C CC-CMW ! MATH 141 Calculus 13 4 C CC-ARP Math 112/115/116 or Math placement test score CHEM 111 & CHEM 111L – General Chemistry I 4 C CC-SCI MATH 111, 115 or Math placement test score ! PHYS 199 Measurement & Analysis in Physics 2 C PR C or better in MATH 115 or higher (offered fall only) UNIV 101 The Student in the University 3 PR/CC or Carolina Core Requirement4 Semester Two (17 Credit Hours) ! ENGL 102 Rhetoric and Composition 3 C CC-CMW C or better in ENGL 101 CC-INF ! MATH 142 Calculus II 4 C CC-ARP MATH 141 CHEM 112 & CHEM 112L – General Chemistry II 4 C PR CHEM 111 or 141 & MATH 111, 115 or higher math; Prereq or Coreq: MATH 122, 141 or higher & CHEM 112L ! PHYS 211 Essentials of Physics I 3 C CC-SCI MATH 141 Carolina Core Requirement4 3 CC Semester Three (16-17 Credit Hours) ! MATH 241 Vector Calculus 3 C PR MATH 142 ! PHYS 212 Essentials of Physics II 3 C PR PHYS 211 & MATH 142 CSCE 145 Algorithmic Design I 4 C CR Prereq or Coreq: MATH 111 or 115 Carolina Core Requirement4 3 CC Foreign language5 or other Carolina Core 3-4 CC-GFL Requirement4 Semester Four (18 Credit Hours) ! MATH 242 Elementary Differential Equations 3 C PR MATH 142 (MATH 242); C or better in or MATH 520 Ordinary Differential Equations MATH 344 or 544 (MATH 520) ! PHYS 307 Introduction to Modern Physics (offered 3 C MR C or better in PHYS 112 & MATH 241 spring only) ! PHYS 311 Intro.