Haloperidol As Prophylactic Treatment for Postoperative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

203050Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 203050Orig1s000 LABELING HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION ------------------------------CONTRAINDICATIONS-------------------------------- These highlights do not include all the information needed to use Hypersensitivity to the drug or any of its components (4) PALONOSETRON HYDROCHLORIDE INJECTION safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for PALONOSETRON ------------------------WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS------------------------- HYDROCHLORIDE INJECTION. • Hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, have been reported with or without known hypersensitivity to other selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists PALONOSETRON HYDROCHLORIDE injection, for intravenous (5.1) use • Serotonin syndrome has been reported with 5-HT3 receptor antagonists alone Initial U.S. Approval: 2003 but particularly with concomitant use of serotonergic drugs (5.2, 7.1) -------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE------------------------ --------------------------------ADVERSE REACTIONS------------------------------- Palonosetron Hydrochloride (HCl) Injection is a serotonin-3 (5-HT3) The most common adverse reactions in chemotherapy-induced nausea and receptor antagonist indicated in adults for: vomiting (≥5%) are headache and constipation (6.1) • Moderately emetogenic cancer chemotherapy -- prevention of acute and delayed nausea and vomiting associated with initial and repeat The most common adverse reactions in postoperative nausea and vomiting (≥ courses (1.1) 2%) are QT prolongation, -

Safety and Efficacy of a Continuous Infusion, Patient Controlled Anti

Bone Marrow Transplantation, (1999) 24, 561–566 1999 Stockton Press All rights reserved 0268–3369/99 $15.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/bmt Safety and efficacy of a continuous infusion, patient controlled anti- emetic pump to facilitate outpatient administration of high-dose chemotherapy SP Dix, MK Cord, SJ Howard, JL Coon, RJ Belt and RB Geller Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, Oncology and Hematology Associates and Saint Luke’s Hospital of Kansas City, Kansas City, MO, USA Summary: and colleagues1 described an outpatient BMT care model utilizing intensive clinic support following inpatient admin- We evaluated the combination of diphenhydramine, lor- istration of HDC. This approach facilitated early patient azepam, and dexamethasone delivered as a continuous discharge and significantly decreased the total number of i.v. infusion via an ambulatory infusion pump with days of hospitalization associated with BMT. More patient-activated intermittent dosing (BAD pump) for recently, equipped BMT centers have extended the out- prevention of acute and delayed nausea/vomiting in patient care approach to include administration of HDC in patients receiving high-dose chemotherapy (HDC) for the clinic setting. Success of the total outpatient care peripheral blood progenitor cell (PBPC) mobilization approach is dependent upon the availability of experienced (MOB) or prior to autologous PBPC rescue. The BAD staff and necessary resources as well as implementation of pump was titrated to patient response and tolerance, supportive care strategies designed to minimize morbidity and continued until the patient could tolerate oral anti- in the outpatient setting. emetics. Forty-four patients utilized the BAD pump Despite improvements in supportive care strategies, during 66 chemotherapy courses, 34 (52%) for MOB chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting continues to be and 32 (48%) for HDC with autologous PBPC rescue. -

5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists in Neurologic and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: the Iceberg Still Lies Beneath the Surface

1521-0081/71/3/383–412$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.118.015487 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 71:383–412, July 2019 Copyright © 2019 by The Author(s) This is an open access article distributed under the CC BY-NC Attribution 4.0 International license. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: JEFFREY M. WITKIN 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists in Neurologic and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: The Iceberg Still Lies beneath the Surface Gohar Fakhfouri,1 Reza Rahimian,1 Jonas Dyhrfjeld-Johnsen, Mohammad Reza Zirak, and Jean-Martin Beaulieu Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Faculty of Medicine, CERVO Brain Research Centre, Laval University, Quebec, Quebec, Canada (G.F., R.R.); Sensorion SA, Montpellier, France (J.D.-J.); Department of Pharmacodynamics and Toxicology, School of Pharmacy, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (M.R.Z.); and Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (J.-M.B.) Abstract. ....................................................................................384 I. Introduction. ..............................................................................384 II. 5-HT3 Receptor Structure, Distribution, and Ligands.........................................384 A. 5-HT3 Receptor Agonists .................................................................385 B. 5-HT3 Receptor Antagonists. ............................................................385 Downloaded from 1. 5-HT3 Receptor Competitive Antagonists..............................................385 2. 5-HT3 Receptor -

The Vomiting Center and the Chemoreceptor Trigger Zone

Pharmacologic Control of Vomiting Todd R. Tams, DVM, Dipl. ACVIM VCA West Los Angeles Animal Hospital Pharmacologic Control of Acute Vomiting Initial nonspecific management of vomiting includes NPO (in minor cases a 6-12 hour period of nothing per os may be all that is required), fluid support, and antiemetics. Initial feeding includes small portions of a low fat, single source protein diet starting 6-12 hours after vomiting has ceased. Drugs used to control vomiting will be discussed here. The most effective antiemetics are those that act at both the vomiting center and the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Vomiting is a protective reflex and when it occurs only occasionally treatment is not generally required. However, patients that continue to vomit should be given antiemetics to help reduce fluid loss, pain and discomfort. For many years I strongly favored chlorpromazine (Thorazine), a phenothiazine drug, as the first choice for pharmacologic control of vomiting in most cases. The HT-3 receptor antagonists ondansetron (Zofran) and dolasetron (Anzemet) have also been highly effective antiemetic drugs for a variety of causes of vomiting. Metoclopramide (Reglan) is a reasonably good central antiemetic drug for dogs but not for cats. Maropitant (Cerenia) is a superior broad spectrum antiemetic drug and is now recognized as an excellent first choice for control of vomiting in dogs. Studies and clinical experience have now also shown maropitant to be an effective and safe antiemetic drug for cats. While it is labeled only for dogs, clinical experience has shown it is safe to use the drug in cats as well. Maropitant is also the first choice for prevention of motion sickness vomiting in both dogs and cats. -

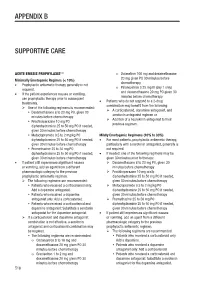

Appendix B Supportive Care

APPENDIX B SUPPORTIVE CARE 1-4 ACUTE EMESIS PROPHYLAXIS o Dolasetron 100 mg and dexamethasone 20 mg given PO 30 minutes before Minimally Emetogenic Regimes (< 10%) chemotherapy • Prophylactic antiemetic therapy generally is not Palonosetron 0.25 mg IV (day 1 only) required. o and dexamethasone 20 mg PO given 30 • If the patient experiences nausea or vomiting, minutes before chemotherapy use prophylactic therapy prior to subsequent Patients who do not respond to a 2-drug treatments. • combination may benefit from the following: One of the following regimens is recommended: A corticosteroid, dopamine antagonist, and Dexamethasone 8 to 20 mg PO, given 30 serotonin antagonist regimen or minutes before chemotherapy Addition of a neurokinin antagonist to their Prochlorperazine 10 mg PO ± previous regimen. diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO if needed, given 30 minutes before chemotherapy Metoclopramide 0.5 to 2 mg/kg PO ± Mildly Emetogenic Regimens (10% to 30%) diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO if needed, • For most patients, prophylactic antiemetic therapy, given 30 minutes before chemotherapy particularly with a serotonin antagonist, generally is Promethazine 25 to 50 mg PO ± not required. diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO if needed, • If needed, one of the following regimens may be given 30 minutes before chemotherapy given 30 minutes prior to therapy: • If patient still experiences significant nausea Dexamethasone 8 to 20 mg PO, given 30 or vomiting, add an agent from a different minutes before chemotherapy pharmacologic category to the previous Prochlorperazine 10 mg orally ± prophylactic antiemetic regimen. diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg PO if needed, The following regimens are recommended: given 30 minutes before chemotherapy Patients who received a corticosteroid only: Metoclopramide 0.5 to 2 mg/kg PO ± Add a dopamine antagonist. -

ASCO's Antiemetics Drug, Dose, and Schedule Table

ASCO 2017 Antiemetics Guideline Update: Drug, Dose, Schedule Recommendations for Antiemetic Regimens Antiemetic Dosing by Chemotherapy Risk Category Agent Dose on Day of Chemotherapy Dose(s) on Subsequent Days High Emetic Risk: Cisplatin and other agents Aprepitant 125 mg oral 80 mg oral; days 2 and 3 Fosaprepitant 150 mg IV NK1 Receptor 300 mg netupitant/0.5 mg palonosetron oral in single Antagonist Netupitant-palonosetron capsule (NEPA) Rolapitant 180 mg oral 2 mg oral or 1 mg or 0.01 mg/kg IV or 1 transdermal Granisetron patch or 10 mg subcutaneous 8 mg oral twice daily or 8 mg oral dissolving tablet Ondansetron twice daily or three 8 mg oral soluble films or 8 mg or 5-HT3 Receptor 0.15 mg/kg IV Antagonista Palonosetron 0.50 mg oral or 0.25 mg IV Dolasetron 100 mg oral ONLY Tropisetron 5 mg oral or 5 mg IV Ramosetron 0.3 mg IV if aprepitant is usedb 12 mg oral or IV 8 mg oral or IV once daily on days 2-4 8 mg oral or IV on day 2; 8 mg oral or IV twice if fosaprepitant is usedb 12 mg oral or IV Dexamethasone daily on days 3-4 if netupitant-palonosetron 12 mg oral or IV 8 mg oral or IV once daily on days 2 to 4 is usedb This table is derived from recommendations in the Antiemetics Guideline Update (2017). This table is a practice tool based on ASCO® practice guidelines and is not intended to substitute for the independent professional judgment of the treating physician. -

Medication Coverage Policy

MEDICATION COVERAGE POLICY PHARMACY AND THERAPEUTICS ADVISORY COMMITTEE POLICY Nausea LAST REVIEW 12/14/2016 THERAPEUTIC CLASS Gastrointestinal Disorders REVIEW HISTORY 11/07, 11/15 LOB AFFECTED Medi-Cal, SJHA (MONTH/YEAR) OVERVIEW Prescription and OTC antiemetic medications are used to relieve nausea and/or prevent or stop vomiting. Some medications have more evidence of providing benefit in specific patient populations, such as patients taking chemotherapy or undergoing a procedure that requires anesthesia. While there are many available agents to relieve the symptoms of nausea and vomiting, non-pharmacologic recommendations should be incorporated into every patient care plan.1,2,3 The purpose of this coverage policy is to review the coverage criteria of HPSJ’s formulary anti-nausea agents (Table 1). Table 1: Available Anti-Nausea Medications Generic (Brand) Strength & Dosage form Formulary Notes Limits 5-HT3 Antagonists Dolasetron Anzemet 50 mg tablet PA; SP Reserved for treatment failure of (Anzemet) Anzemet 100 mg tablet PA; SP Ondansetron and Granisetron Tablets Reserved for members with documented Granisetron 3.1 mg/24 hr PA; SP inability to take medications by mouth, transdermal patch (Sancuso Granisetron (Kytril, including ODT formulations. Sancuso) Reserved for patients with documented Granisetron Tablets (Kytril) PA treatment failure of dose optimized Ondansetron therapy Ondansetron 4 mg disintegrating QL tablet Ondansetron 8 mg disintegrating QL Limit 60 tablets per 30 days. tablet Ondansetron Ondansetron Hcl 4 mg tablet QL (Zofran) Ondansetron Hcl 8 mg tablet QL Ondansetron 4 mg/5 ml solution NF Ondansetron 40 mg/20 ml vial NF Ondansetron HCL 4 mg/2 ml vial NF Reserved for use in patients receiving Palonosetron Aloxi 0.25 mg/5 ml intravenous highly-emetogenic chemotherapy, with PA; SP (Aloxi) solution treatment failure of ondansetron, or documented inability to swallow. -

Name of Medicine

HALDOL® haloperidol decanoate NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME HALDOL haloperidol decanoate 50 mg/mL Injection HALDOL CONCENTRATE haloperidol decanoate 100 mg/mL Injection 2. QUANTITATIVE AND QUALITATIVE COMPOSITION HALDOL 50 mg/ml Haloperidol decanoate 70.52 mg, equivalent to 50 mg haloperidol base, per millilitre. HALDOL CONCENTRATE 100 mg/ml Haloperidol decanoate 141.04 mg, equivalent to 100 mg haloperidol base, per millilitre. For a full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Injection (depot) HALDOL Injection (long acting) is a slightly amber, slightly viscous solution, free from visible foreign matter, filled in 1 mL amber glass ampoules. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications HALDOL is indicated for the maintenance therapy of psychoses in adults, particularly for patients requiring prolonged parenteral neuroleptic therapy. 4.2 Dose and method of administration Administration HALDOL should be administered by deep intramuscular injection into the gluteal region. It is recommended to alternate between the two gluteal muscles for subsequent injections. A 2 inch-long, 21 gauge needle is recommended. The maximum volume per injection site should not exceed 3 mL. The recommended interval between doses is 4 weeks. DO NOT ADMINISTER INTRAVENOUSLY. Patients must be previously stabilised on oral haloperidol before converting to HALDOL. Treatment initiation and dose titration must be carried out under close clinical supervision. The starting dose of HALDOL should be based on the patient's clinical history, severity of symptoms, physical condition and response to the current oral haloperidol dose. Patients must always be maintained on the lowest effective dose. CCDS(180302) Page 1 of 16 HALDOL(180712)ADS Dosage - Adults Table 1. -

Proposal for the Inclusion of Anti-Emetic Medications (For Children) in the Who Model List of Essential Medicines

Second Meeting of the Subcommittee of the Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines Geneva, 29 September to 3 October 2008 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF ANTI-EMETIC MEDICATIONS (FOR CHILDREN) IN THE WHO MODEL LIST OF ESSENTIAL MEDICINES REPORT Marc Bevan, Elizabeth Seil, Robin Bell and Jane Robertson Discipline of Clinical Pharmacology School of Medicine and Public Health Faculty of Health University of Newcastle Level 5, Clinical Sciences Building, NM2 Calvary Mater Hospital Edith Street, Waratah, 2298 New South Wales AUSTRALIA Tel +61-02-49211726 Fax + 61-02-49602088 WHO EML – anti-emetics – June 2008 1. Summary statement of the proposal Anti-emetic medications (anti-histamines, dopamine antagonists and serotonin 5-HT3 antagonists) are proposed for inclusion in the World Health Organization (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines for the management of acute gastroenteritis in children. 2. Name of focal point in WHO submitting or supporting the application 3. Name of the organisation preparing the application Discipline of Clinical Pharmacology, School of Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Health, University of Newcastle, Level 5, Clinical Sciences Building, NM2, Calvary Mater Hospital, Edith Street, Waratah, 2298, New South Wales, Australia. 4. International Nonpropriety Name (INN, generic name) of the medicine The proposal reviews relevant data regarding four anti-emetic medications; metoclopramide and domperidone (dopamine agonists), promethazine (anti- histamine) and ondansetron (serotonin 5-HT3 antagonist). 5. Formulation considered for inclusion The formulations of metoclopramide, domperidone, promethazine and ondansetron considered for inclusion are shown in Table 1. Table 1: Formulations of ant-emetic medications considered for inclusion Formulation Comment Metoclopramide Injection or oral - Injection, tablet and oral liquid formulations are preparation (tablet, currently listed on WHO EML for children. -

Antiemetics Review 02/17/2009

Antiemetics Review 02/17/2009 Copyright © 2004 - 2009 by Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage and retrieval system without the express written consent of Provider Synergies, L.L.C. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Attention: Copyright Administrator Intellectual Property Department Provider Synergies, L.L.C. 5181 Natorp Blvd., Suite 205 Mason, Ohio 45040 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational -

A Narrative Review of Tropisetron and Palonosetron for the Control of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting

Review Article Page 1 of 19 A narrative review of tropisetron and palonosetron for the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting Yunpeng Yang, Li Zhang Medical Oncology Department, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou 510060, China Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: All authors; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: All authors; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors. Correspondence to: Li Zhang. Medical Oncology Department, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center, 651 Dongfeng East Road, Guangzhou 510060, China. Email: [email protected]. Abstract: Review the clinical evidence of tropisetron or palonosetron, an old- and new-generation serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) type 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist (RA), respectively, for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients with cancer, and evaluate any difference in efficacy trends. A literature search of the EMBASE and PubMed databases was performed to identify publications of intravenous (IV) tropisetron (generic forms or Navoban®) for the treatment of CINV in patients with various cancers. Data from the pivotal clinical studies evaluating the IV formulation of Aloxi® (palonosetron HCl) were also considered. The effectiveness and safety of each antiemetic was summarized. Sixteen papers for tropisetron fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were extracted for full analysis; publications from six pivotal palonosetron clinical trials were considered. No direct data comparisons could be made between the two drugs, due to the varying definitions of efficacy endpoints between studies. For tropisetron, the rates of no emesis were lower in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC) versus moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC). -

Dolasetron Mesylate)

Rx only ANZEMET ® Tablets (dolasetron mesylate) DESCRIPTION ANZEMET (dolasetron mesylate) is an antinauseant and antiemetic agent. Chemically, dolasetron mesylate is (2α,6α,8α,9aß)-octahydro-3-oxo-2,6-methano-2H-quinolizin-8-yl-1H indole-3-carboxylate monomethanesulfonate, monohydrate. It is a highly specific and selective serotonin subtype 3 (5-HT3) receptor antagonist both in vitro and in vivo. Dolasetron mesylate has the following structural formula: The empirical formula is C19H20N2O3 • CH3SO3H • H2O, with a molecular weight of 438.50. Approximately 74% of dolasetron mesylate monohydrate is dolasetron base. Dolasetron mesylate monohydrate is a white to off-white powder that is freely soluble in water and propylene glycol, slightly soluble in ethanol, and slightly soluble in normal saline. Each ANZEMET Tablet for oral administration contains dolasetron mesylate (as the monohydrate) and also contains the inactive ingredients: carnauba wax, croscarmellose sodium, hypromellose, lactose, magnesium stearate, polyethylene glycol, polysorbate 80, pregelatinized starch, synthetic red iron oxide, titanium dioxide, and white wax. The tablets are printed with black ink, which contains lecithin, pharmaceutical glaze, propylene glycol, and synthetic black iron oxide. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Dolasetron mesylate and its active metabolite, hydrodolasetron (MDL 74,156), are selective serotonin 5-HT3 receptor antagonists not shown to have activity at other known serotonin receptors and with low affinity for dopamine receptors. The serotonin 5-HT3 receptors are located on the nerve terminals of the vagus in the periphery and centrally in the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the area postrema. It is thought that chemotherapeutic agents produce nausea and vomiting by releasing serotonin from the enterochromaffin cells of the small intestine, and that the released serotonin then activates 5-HT3 receptors located on vagal efferents to initiate the vomiting reflex.