At the Crossroads: Prospects for Kentucky's Educational Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ccfiber TV Channel Lineup

CCFiber TV Channel Lineup Locals+ Expanded (cont'd) Stingray Music Premium Channels (cont'd) 2 WKRN (ABC) 134 Travel Channel Included within Ultimate Cinemax Package 4 WSMV (NBC) 140 Viceland 210 Adult Alternative 5 WTVF (CBS) 144 OWN 211 ALT Rock Classics 330 5StarMAX 6 WTVF 5+ 145 Oxygen 212 Americana 331 ActionMAX East 8 WNPT (PBS) 146 Bravo 213 Bluegrass 332 ActionMAX West 9 QVC 147 E! 214 Broadway 333 MaxLatino 10 QVC2 148 We TV 215 Chamber Music 334 Cinemax East 12 ION 149 Lifetime 216 Classic Masters 335 Cinemax West 14 Qubo 151 Lifetime Movie Network 217 Classic R&B Soul 336 MoreMAX East 17 WZTV (FOX) 153 Hallmark Channel 218 Classic Rock 337 MoreMAX West 19 EWTN 154 Hallmark Movie 219 Country Classics 338 MovieMAX 20 Shop HQ 155 Hallmark Drama 220 Dance Clubbin 339 OuterMAX 21 Inspiration 160 Nick Jr. 221 Easy Listening 340 ThrillerMAX East 22 TBN 161 Disney Channel 222 Eclectic Electronic 341 ThrillerMAX West 25 WPGD 164 Cartoon Network 223 Everything 80's 27 CSPAN 165 Discovery Family 224 Flashback 70's Starz Package 28 CSPAN 2 166 Universal Kids 225 Folk Roots 29 CSPAN 3 168 Nickelodeon 226 Gospel 360 Starz West 30 WNPX (ION) 189 TV Land 227 Groove Disco and Funk 361 Starz East 32 WUXP (MY TV) 190 MTV 228 Heavy Metal 362 Starz Kids East 35 Jewelry TV 191 MTV 2 229 Hip Hop 363 Starz Kids West 36 HSN 192 VH1 230 Hit List 364 Starz in Black West 37 HSN2 194 BET 231 Holiday Hits 365 Starz in Black East 38 WJFB (Shopping) 200 CMT 232 Hot Country 366 Starz Edge West 41 WHTN (CTN) Ultimate (Includes Locals+ & Expanded) 233 Jammin -

Eastern Progress

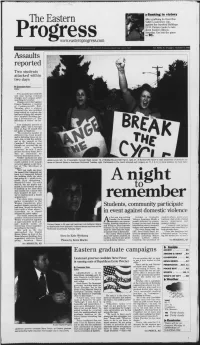

—, ■i ► Basking in victory After grabbing its first Ohio The Eastern Valley Conference win, against the Samford Bulldogs 13-10, Eastern looks to take down Eastern Illinois Saturday. Get into the game Pro gress on Bl. *—^ www.easternprogress.com ilern Konlui ky University sines I'li"/ Vol 82/No 8. 18 pages October 9 2003 Assaults reported Two students attacked within two days BY CASSQNDRA KWBY Editor Two assaults last week left one man facing criminal charges and campus police searching for another. Charges were filed against Francis Stapleton, a resident of Commonwealth Hall. Tuesday after a student reported she was grabbed from behind by a person she had been talking with outside the Campbell Building dur- ing a production of "The Merchant of Venice" on Oct. 1. Tom Lindquist, director of public safety, said it was tips from an Aug. 26 assault that led police to Stapleton. "We received a number of different tips from people and in following those up, we were able to link this individ- ual to the assault at the Campbell Building, even though we received the tip before the incident occurred," he said. "I can't go into any more detail, but il was an individual we received information about." Neither Lindquist nor play director Jeffrey Boord-Dill Jenna Lyons, left. 18, of Lexington, Hannah Reed, center, 19, of Shelbyville and Kelli Harris, right, 21, of Barbourville march to raise awareness of domestic vio- could confirm if the assault lence on Second Street in downtown Richmond Tuesday night. Participants in the march shouted such slogans as, "2, 4. -

IN the COURT of APPEALS of TENNESSEE at NASHVILLE June 09, 2014 Session

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE June 09, 2014 Session THE TENNESSEAN, ET AL. V. METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, ET AL. Appeal from the Chancery Court for Davidson County No. 14156IV Russell T. Perkins, Chancellor No. M2014-00524-COA-R3-CV - Filed September 30, 2014 Various media outlets made request under the Tennessee Public Records Act for access to records accumulated and maintained by the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department in the course of its investigation and prosecution of an alleged rape in a campus dormitory. When the request was refused, the outlets a filed petition in Chancery Court in accordance with Tennessee Code Annotated § 10-7-505; the State of Tennessee, District Attorney General and alleged victim were permitted to intervene. The court held the required show cause hearing and, following an in camera inspection, granted petitioners access to four categories of records and documents. Petitioners, as well as the Metropolitan Government and Intervenors appeal, raising numerous and various statutory and constitutional issues. We have determined that the records sought are currently exempt from disclosure due to the continuing police investigation and pending prosecution; accordingly, we reverse the judgment of the Chancery Court and dismiss the petition. Tenn. R. App. P. 3 Appeal as of Right; Judgment of the Chancery Court Reversed; Petition Dismissed RICHARD H. DINKINS, J., delivered the opinion of the court, in which FRANK G. CLEMENT, JR., P. J., M. S., joined. W. NEAL MCBRAYER, J., filed a dissenting opinion. Robb S. Harvey and Lauran M. Sturm, Nashville, Tennessee, for the appellants, The Tennessean, Associated Press, Chattanooga Times Free Press, Knoxville News Sentinel, Tennessean Coalition for Open Government, Inc., Tennessee Associated Press Broadcasters, WZTV Fox 17, WBIR-TV Channel Ten, WTVF-TV Channel Five, The Commercial Appeal, and WSMV-TV Channel Four. -

The Opportunity Ahead MONETIZING the MEDIA CONSUMER in 2017 and BEYOND UBS Dec

The Opportunity Ahead MONETIZING THE MEDIA CONSUMER IN 2017 AND BEYOND UBS Dec. 6 // 2016 Safe Harbor/Disclosures This presentation contains forward-looking statements that involve a number of risks and uncertainties. For this purpose, any statements contained herein that are not statements of historical fact may be deemed to be forward-looking statements. Without limiting the foregoing, the words “believes,” “anticipates,” “plans,” “expects,” “intends,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Important factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from those indicated by such forward-looking statements are set forth in The E.W. Scripps Company’s annual report on Form 10-K for the year ended Dec. 31, 2015, as filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. We undertake no obligation to publicly update any forward-looking statements to reflect events or circumstances after the date the statement is made. 2 The Year Rich Boehne Ahead PRESIDENT, CHAIRMAN & CEO Rebuilding Scripps For Growth Buy Complete Buy Newsy Cracked; Stitcher separation of Divest Launch original Scripps “Peanuts” programming National brands Networks and unit, two Buy two Granite move to 45% of access shows Interactive licensing TV stations Digital revenue 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 ECONOMIC CRISIS 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 Combine digital Propose spin off Close Denver Terminate Scripps Spin/combine operations; of cable newspaper, Howard News newspapers with networks to announce Journal reset investment and Service; Launch -

Remarks at a Bush-Cheney Luncheon in Louisville February 26, 2004

Administration of George W. Bush, 2004 / Feb. 26 percent bracket permanent, they pay with all their heart, people who are putting $1,000 next year. We’re running up taxes food on the table. on this family, and it affects their ability I want to repeat to you what I said be- to make decisions. It affects their future. fore. This country has overcome a lot, and It’s just—it doesn’t make any sense for we’re moving forward with optimism and Congress not to make the tax relief perma- confidence. You know why? Because we’ve nent. And the best way that I can possibly got great people. And I’m proud to be the tell the story—they’re used to me—is all leader of such a strong nation. they’ve got to do is listen to what tax relief Thank you all for coming. God bless. meant for people in their lives and what NOTE tax increases would do. And so I call upon : The President spoke at 10:52 a.m. at ISCO Industries. In his remarks, he referred Congress to listen to the voices of the peo- to Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, ple out here struggling to get ahead in husband of Secretary of Labor Elaine L. America, people who are making good deci- Chao; Gov. Ernie Fletcher and Lt. Gov. sions, people who are doing their duty as Steve Pence of Kentucky; and Mayor Jerry responsible citizens to love their children E. Abramson of Louisville, KY. Remarks at a Bush-Cheney Luncheon in Louisville February 26, 2004 Thank you all for coming. -

Report Summary: Total Hits:44 Total Audience Impressions:2647204 Total Publicity Value:$119838.70 05:36:32.00

† Report Summary: Total Hits:44 Total Audience Impressions:2,647,204 Total Publicity Value:$119,838.70 Market: Nashville TN [NV] [29] HUT: 1,024,560 DMA%: 0.89 Date: 01/27/2014 Time: 5:30am Aired On: WTVF Affiliate: CBS Show: Morning Report Early Edition (2/2) Estimated Audience Number: 91,071 | Estimated Publicity Value: $4,122.78 05:36:32.00 That is john godwin talking about all the people up there lined up sunday to shake his hand and maybe an autograph or picture or two-godwin says appearances are flattering, but it is time to get back to work. Going back home. Were starting to film tomorrow. The rest of season five. And back to reality. The nashville boat and sports show wrapped up yesterday afternoon at the music city center. It was a night of amazing performances and some big honors and aefrn wedding. The 56 and even a wedding. The 56th grammy awards wrapped up with some unforgettable moments. ? Daft punk won album of the year and record of the year at the 56th annual grammy award Market: Nashville TN [NV] [29] HUT: 1,024,560 DMA%: 0.89 Date: 01/27/2014 Time: 5:00am Aired On: WKRN Affiliate: ABC Show: Nashville's News 2 This Morning at 5am (1/2) Estimated Audience Number: 30,389 | Estimated Publicity Value: $1,375.71 05:11:24.00 The presidents address is expected to focus on jobs. According to metro schols, the white house asked about many metro schools, but decided to visit mcgavock high school because of how it has been re- invented and become a nationally recognized model academy in the past few years. -

Channel # Channel # WKRN-DT 2.1 A&E HD 57.2 WKRN-DT2 2.2 AMC

Channel # Channel # WKRN-DT 2.1 A&E HD 57.2 WKRN-DT2 2.2 AMC HD 59.1 WKRN-DT3 2.3 Animal Planet HD 59.2 Big Ten Network HD 3.2 AXS TV HD 60.1 WSMV-DT 4.1 BBC America HD 60.2 WSMV-DT2 4.2 BET HD 61.1 WSMV-DT3 4.3 Big Ten Network HD 3.2 WTVF-DT 5.1 Bloomberg Television HD 61.2 WTVF-DT2 5.2 Bravo HD 62.1 WTVF-DT3 5.3 Cartoon Network HD 62.2 WNPT-DT 8.1 CBS Sports Network HD 87.1 WNPT-DT2 8.2 CGTN-E 71.1 MTSU 9.1 CheddarU 11.1 MTSU 10.1 CMT HD 63.1 CheddarU 11.1 CNBC HD 57.1 DSI Guide Channel 11.2 CNN HD 55.1 WZTV-DT 17.1 Comedy Central HD 63.2 WNPX-DT 28.1 Cooking Channel HD 64.1 WNPX-DT2 28.2 CSPAN1 80.1 WNPX-DT3 28.3 CSPAN2 80.2 WNPX-DT4 28.4 Destination America HD 64.2 WNPX-DT5 28.5 Discovery Channel HD 65.1 WNPX-DT6 28.6 Discovery Family Channel HD82.2 WUXP-DT 30.1 Disney Channel HD 83.1 WUXP-DT2 30.2 Disney XD 83.2 CNN HD 55.1 DSI Guide Channel 11.2 MSNBC HD 55.2 E! Entertainment HD 65.2 Fox News Channel HD 56.1 ESPN HD 87.2 Fox Business Network HD 56.2 ESPN2 HD 88.1 CNBC HD 57.1 ESPNews HD 88.2 A&E HD 57.2 ESPNU HD 89.1 WNAB-DT 58.1 Food Network HD 66.1 WNAB-DT2 58.2 Fox Business Network HD 56.2 WNAB-DT3 58.3 Fox News Channel HD 56.1 AMC HD 59.1 Freeform HD 66.2 Animal Planet HD 59.2 Fuse HD 84.1 AXS TV HD 60.1 FX HD 67.1 BBC America HD 60.2 Golf Channel HD 86.1 BET HD 61.1 Hallmark Channel HD 67.2 Bloomberg Television HD 61.2 Hallmark Movies and Mysteri68.1 Bravo HD 62.1 HGTV HD 68.2 Cartoon Network HD 62.2 History Channel HD 69.1 CMT HD 63.1 HLN HD 69.2 Comedy Central HD 63.2 IFC HD 70.1 Cooking Channel HD 64.1 Investigation Discovery -

Benefits Derived from Western's Intercollegiate Athletic Program

• BENEFllS UEHIVEO FRO~I WESTERN'S INTEHCOLLEG IATE ATHLETIC PHOGRAM In April 1982 an i ndepende nt comn ission was established by the Nationa l Col legiate At hletic Association to study col lege athletics. Its purpose was to concentrate on athletic probl ems and concerns i n Highe r Education. A.. significant sect ion of that report focused on the role of intercol legiate " atnletics at an educational institution with emphasis on the li nk that has existed between amateur athletics and higher educati on during the past- century. In referring to this link . the comnittee declared : " ... one cou ld search at length for a theoretical justification fo r this linkage. but the exercise is meani ngless . The fact is that intercollegiate ath letics today is firmly established as part of the fabric of our education system , and it wil l continue to be in the future . The reason for thi s is clear. Despite all of the problems that have been associated with col lege athletic programs , their contributions to the overall well -being of higher education have outwe i glled their negative aspects. " I am sure each of us agree wi th the report when it states, "the primary function of any educational in stitution is to educa t e its constituency." However . it further conc ludes that "in our society, colleges and universities also serve functions that are ancillary to their basic miss ion" and that these functions are enormously impo rtant to those who share in them . For example, some of these anc ill ary functions are pub l ic service; developing and sustaining an interest in the fine arts ; and intercol l egiate athletic programs . -

Local TV Coverage of the 2000 General Election

Local TV Coverage of the 2000 General Election Martin Kaplan, Principal Investigator Matthew Hale, Research Director Most Americans say they get most of their news from local television. We analyzed the local news programs watched by most Americans to find out what news they received on the 2000 general election. We analyzed local broadcast television coverage on 74 stations in 58 markets in the last 30 days before the election to see whether a White House panel’s recommendation of airing five minutes of candidate centered discourse (CCD) a night had an impact. We found that the 74 stations ran an average of 74 seconds of CCD per night. The average sound bite was 14 seconds; 55 percent of the stories focused on strategy; 24 percent focused on issues; and less than 1 percent were adwatch stories. Local TV News Coverage of the 2000 General Election The Norman Lear Center The Ford Foundation The Alliance for Better Campaigns The Norman Lear Center is a The Alliance for Better Campaigns is a The Ford Foundation is a resource for multidisciplinary research and public policy public interest group that seeks to innovative people and institutions center exploring implications of the improve elections by promoting worldwide. For more than a century, its convergence of entertainment, commerce campaigns in which the most useful goals have been to strengthen democratic and society. On campus, from its base in information reaches the greatest values; reduce poverty and injustice; the USC Annenberg School for number of citizens in the most engaging promote international cooperation; and Communication, the Lear Center builds ways. -

Unbridled Voice!!!

Unbridled Voice March 2006 Military Members Serve Country While Working for the Commonwealth Pride runs deep among those who serve in the military. Add to their duties a full time state job where they serve the Commonwealth of Kentucky as well, and you have a citizen giving back two-fold. “During Operation Iraqi Freedom we flew missions into 59 locations in 38 countries in the Middle East, Southwest Asia, Europe and Africa,” said Colonel Steve Bullard of the Kentucky Air National Guard in Louisville. Bullard was mobilized for 26 months and commanded a composite National Guard and Re- serve C-130 aircraft squadron in Germany. Besides serving in the Air National Guard, Bullard works full time as the Director of Administrative Services in the Department of Military Affairs at the Boone National Guard Center. “We regularly send out two airplanes and three crews on 17-to-45 day deploy- ments to places like Iraq, Bosnia and Central/South America,” Bullard said. Responsible for flying in troops, gear and humanitarian supplies on C-130 cargo planes, Bullard says soldiers are quiet going in to combat zones and boisterous returning home. Regardless your position in state government or elsewhere, he says leaving home is the greatest challenge. “One of the reasons I left active duty was because I was gone so much. I averaged 253 days on the road.” With a wife and three children, Bullard said he missed many winter holidays including two spent in the Middle East. Now Bullard is gratified to have the best of both worlds, working in Military Affairs and in the Air National Guard. -

Alabama at a Glance

ALABAMA ALABAMA AT A GLANCE ****************************** PRESIDENTIAL ****************************** Date Primaries: Tuesday, June 1 Polls Open/Close Must be open at least from 10am(ET) to 8pm (ET). Polls may open earlier or close later depending on local jurisdiction. Delegates/Method Republican Democratic 48: 27 at-large; 21 by CD Pledged: 54: 19 at-large; 35 by CD. Unpledged: 8: including 5 DNC members, and 2 members of Congress. Total: 62 Who Can Vote Open. Any voter can participate in either primary. Registered Voters 2,356,423 as of 11/02, no party registration ******************************* PAST RESULTS ****************************** Democratic Primary Gore 214,541 77%, LaRouche 15,465 6% Other 48,521 17% June 6, 2000 Turnout 278,527 Republican Primary Bush 171,077 84%, Keyes 23,394 12% Uncommitted 8,608 4% June 6, 2000 Turnout 203,079 Gen Election 2000 Bush 941,173 57%, Gore 692,611 41% Nader 18,323 1% Other 14,165, Turnout 1,666,272 Republican Primary Dole 160,097 76%, Buchanan 33,409 16%, Keyes 7,354 3%, June 4, 1996 Other 11,073 5%, Turnout 211,933 Gen Election 1996 Dole 769,044 50.1%, Clinton 662,165 43.2%, Perot 92,149 6.0%, Other 10,991, Turnout 1,534,349 1 ALABAMA ********************** CBS NEWS EXIT POLL RESULTS *********************** 6/2/92 Dem Prim Brown Clinton Uncm Total 7% 68 20 Male (49%) 9% 66 21 Female (51%) 6% 70 20 Lib (27%) 9% 76 13 Mod (48%) 7% 70 20 Cons (26%) 4% 56 31 18-29 (13%) 10% 70 16 30-44 (29%) 10% 61 24 45-59 (29%) 6% 69 21 60+ (30%) 4% 74 19 White (76%) 7% 63 24 Black (23%) 5% 86 8 Union (26%) -

Kentucky and the New Economy/Challenges for the Next

Kentucky and the New Economy Challenges for the Next Century THE CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS Kentucky Long-Term Policy Research Center Kentucky and the New Economy Challenges for the Next Century THE CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS Edited and Compiled by Suzanne King Billie M. Sebastian Kentucky Long-Term Policy Research Center Published By Kentucky Long-Term Policy Research Center 111 St. James Court Frankfort, Kentucky 40601 2001 Printed with state funds Available in alternative formats upon request ii Kentucky Long-Term Policy Research Center BOARD OF DIRECTORS Rep. Steve Nunn, Chair Betty Griffin, Vice Chair EXECUTIVE BRANCH Diane Hancock Mary E. Lassiter Donna B. Moloney James R. Ramsey LEGISLATIVE BRANCH Sen. Tom Buford Sen. Alice Forgy Kerr Rep. “Gippy” Graham Sen. Dale Shrout AT-LARGE MEMBERS Evelyn Boone Ron Carson Paul B. Cook Daniel Hall Jennifer M. Headdy Sheila Crist Kruzner Penny Miller Robert Sexton Alayne L. White EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Michael T. Childress The Kentucky Long-Term Policy Research Center is governed by a 21-member board of directors, including four appointees from the executive branch, six from the legislative branch, and eleven at-large members representing organizations, universities, local governments, and the private sector. From the at-large component of the board, six members are appointed by the Governor and five by the Legislative Research Commission. In accordance with its authorizing legislation, the Center is attached to the legislative branch of Kentucky state government. iii iv Preface s part of its mission to advise and inform the Governor, the General Assembly, and the public about the Aimplications of trends influencing the state’s future, the Kentucky Long-Term Policy Research Center presents the proceedings from its seventh annual conference, which was held in Covington at the Northern Kentucky Convention Center in November 2000.