An Exploration of Family History Through Autobiography and Record Analysis by Anna Peabody a THESIS Su

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

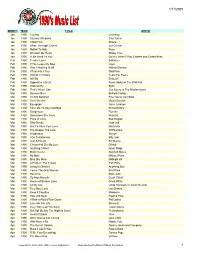

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/09/2016 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/09/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Crazy - Patsy Cline Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Don't Stop Believing - Journey Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond My Girl - The Temptations Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Ex's & Oh's - Elle King Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Let It Go - Idina Menzel Me Too - Meghan Trainor Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-Lot EXPLICIT Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals H.O.L.Y. - Florida Georgia Line Hello - Adele Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd When We Were Young - Adele Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Summer Nights - Grease Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Piano Man - Billy Joel I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys All Of Me - John Legend Turn The Page - Bob Seger These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Way - Frank Sinatra (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's 7 Years - Lukas Graham Wannabe - Spice Girls A Whole New World - -

DJ Master Mix CD List

DJ Master Mix CD List ***Background Music*** 25 Gloria in Excelsis Deo (vocal) 2 Pennsylvania 6-5000 3 Chatanooga Choo-Choo 101 Strings Play Frank Sinatra ***Background Music*** 4 String of pearls 1 All the way 25 All Time Christmas Favorites Di 5 In the mood 2 Strangers in the night 1 Jingle bells (pop) 6 Sunrise serenade 3 Fly me to the moon 2 Joy to the world (pop) 7 Johnson rag 4 New York, New York 3 Deck the halls (pop) 8 American patrol 5 The lady is a tramp 4 We wish you a merry Christmas (pop) 9 Kalamazoo 6 Come fly with me 5 Hark the herald angels sing (pop) 10 Bugle call rag 7 I've got you under my skin 6 Jolly old St. Nicholas (pop) 11 Anvil chorus 8 Young at heart 7 O Christmas Tree (pop) 12 Tuxedo junction 9 Just the way you look tonight 8 Auld Lang Syne (pop) 13 Moonlight cocktail 10 You're nobody till somebody loves you 9 The twelve days of Christmas(pop) 14 Serenade in blue 11 The shadow of your smile 10 We three Kings (pop) 12 Three coins in the fountain 11 Ave Maria (vocal) ***Background Music*** ***Background Music*** 12 Gloria a Jesu(vocal) Big Band Spectacular Vol. II 13 Alleluia (vocal) 1 One O'clock jump 15 of the World's Greatest Love Son 14 II Est Ne Le Divin Enfant 2 Jersey bounce 1 Wind beneath my wings 15 Silver Bells (vocal) 3 Frankie and Johnny were lovers 2 Always on my mind 16 Alleluiah 4 Stomping at the Savoy 3 All out of love 17 For unto us a child is born 5 Down south camp meeting 4 Dust in the wind 18 The trumpet shall sound 6 Jumping at the woodside 5 Lady in red 19 Amen 7 Let's dance 6 Up where we -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 25/10/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 25/10/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Wannabe - Spice Girls Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Zombie - The Cranberries I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Don't Stop Believing - Journey Dancing Queen - ABBA Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Perfect - Ed Sheeran Piano Man - Billy Joel Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Africa - Toto Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Santeria - Sublime Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Someone Like You - Adele Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Valerie - Amy Winehouse Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals What A Wonderful World - Louis Armstrong Summer Nights - Grease Jackson - Johnny Cash Jolene - Dolly Parton Crazy - Patsy Cline Let It Go - Idina Menzel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding My Girl - The Temptations All Of Me - John Legend I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Turn The Page - Bob Seger Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn My Way - Frank Sinatra These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter I Want It That Way - Backstreet -

2013 NBA All-Star Game and Related Events

1 Cover Sheet Event: 2013 National Basketball Association (NBA) All-Star Game Date: February 8-18, 2013 Location: Houston, Texas Report Date: November 20, 2014 2013 National Basketball Association (NBA) All-Star Game 2 Post Event Analysis 2013 National Basketball Association (NBA) All-Star Game I. Introduction This post-event analysis is intended to evaluate the short-term tax benefits to the state through review of tax revenue data to determine the level of incremental tax impact to the state of Texas from the event. A primary purpose of this analysis is to determine the reasonableness of the initial incremental tax estimate made by the Comptroller’s office prior to the event. The initial estimate is included in Appendix B. Large events, particularly “premier events” such as this one, with heavy promotion, corporate sponsorship and spending, and “luxury” spending by visitors, will tend to create significant ripples in the local economy, and in fact, even the regional economy outside the immediate area considered in this report. The purpose of this report is to analyze the changes in tax collections during the period in which the event occurred. An analysis of tax data will shed some light on tax impact, however, several outside factors must be considered when looking at tax collections data during the time of the event. While these events might bring in a significant number of out- of-state visitors, they might also entice many in-state residents to travel and spend their dollars in this area. Additionally, while an analysis of tax data may shed some light on tax impact, some factors must be considered when looking at tax collections data during the time of the event. -

Wisconsin HOUSE RABBIT NEWS

Wisconsin HOUSE RABBIT NEWS Spring 2018 | Volume XXV | Issue 1 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Rabbit photograph by Casandra Parshall | Designed by Kanae Hoshina WHRS Chapter News What’s happening at Wisconsin House Rabbit Society? HOPPY HOUR Twitch Fund Drive information email [email protected]. RETROSPECTIVE A special fundraiser for Wisconsin House PG 4 Bunny Day at HAWS, April 15th, 12-4pm Rabbit Society will began on March 1st. SPRINGTIME During the month of March, Timid Bunny, a The program for this year’s HAWS Bunny Day PARASITE RISKS Twitch online content creator, will promote is now set. Dr. April Wittenburg from Brook PG 6 WHRS during her streams. The purpose is to Falls Veterinary Hospital will speak on “Senior make people aware of all WHRS does to help Citizen Rabbits: How to Keep Your Bunny A SAFE OUTDOOR rabbits. Both WHRS members and the event Hopping in Old Age.” Dave Stevenson, PhD, will PLAY AREA organizers, Romy and Mike, have taken lots speak about “How Rabbits Became Pets: New PG 7 of video footage behind the scenes and at Evidence from DNA.” As always, we will have hay for sale, great items in the Bunny Boutique, RUBY-EYED RABBITS our public events. So, please tune in to see us at work. The program will also promote our and free educational materials. This year we PG 8 Easter message that rabbits are not seasonal will invite you take quizzes on rabbit diet, basic FORAGING FOR novelties, and it will attempt to raise donations environment, toys, and wellness and grooming. SPRING FLOWERS for us as well as showcase our adoptable PG 11 rabbits. -

Iowa Doc Disapproved Publications List - June 2019

IOWA DOC DISAPPROVED PUBLICATIONS LIST - JUNE 2019 DECISION # TITLE CODE DATE A & M NEWSLETTER (5-08 / #33 / 10-09 / 10-10 / #62 / 2,4,9-11 / A #66,68,73,79,85,86 / 5,9,10-12) A A BATTLE FOR THE SOUL OF ISLAM (by Jasser) May-16 A A BILLION WICKED THOUGHTS (by Ogas & Goddan) Feb-14 A A BLACK MAN IN THE WHITE HOUSE (by Belcher) Jan-19 D A CHILD OF A CRACKHEAD (by Speight) F2 Aug-15 A A DENSITY OF SOULS (by Rice) Nov-14 A A DIFFERENT KIND OF CELL (by Jones) Nov-18 A A DOLLAR OUTTA FIFTEEN CENTS (by McGill) Nov-15 A A FUNNY THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY TO HEAVEN (by Taylor) Feb-17 A A GAME OF THRONES - #6 (by Martin) Aug-17 A A GANGSTER AND A GENTLEMAN (by Swinson & Diamond) May-16 A A GANGSTER'S GIRL (by Chunichi) May-16 A A GANGSTER'S GIRL SAGA (by Chunichi) May-16 D A GARDEN OF WILDFLOWERS (by Art) F6 Nov-14 A HISTORY OF THE NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS (by Nikolaus A Wachsmann) Jan-19 A A HOLY BOOK (Original Edition) Nov-16 A A HUSTLER'S WIFE (by Turner) Jun-18 A A LION AMONG MEN (by Maguire) Jul-15 D A LOVER'S COCK (by Rimbaud & Verlaine) F10/F11 Oct-15 A A MEASURE OF MADNESS (by Merrick) May-15 A A MILLION LITTLE PIECES (by Frey) Feb-18 A A MOMENT OF SILENCE (by Souljah) Oct-17 A A PAGAN ANTI-CAPITALIST PRIMER Jun-16 D A POLISHED SOUL - The Mike Rae Anderson Story (by Anderson) F6 Jan-15 A A ROSE AMONG THORNS (by Dasaint) Feb-16 A A SEASON IN HELL (Preface by Patti Smith) Mar-18 D A SECRET LIFE (Anonymous) F11 Nov-14 A A SENSE OF FREEDOM (by Boyle) Nov-17 A A SPANKING ROMANCE (by Rainford) Oct-16 D A TIME TO KILL (by Grisham) F2/F7/F10 Jan-14 -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 17/12/2016 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 17/12/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs (H?D) Planet Earth My One And Only Hawaiian Hula Eyes Blackout I Love My Baby (My Baby Loves Me) On The Beach At Waikiki Other Side I'll Build A Stairway To Paradise Deep In The Heart Of Texas 10 Years My Blue Heaven What Are You Doing New Year's Eve Through The Iris What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Long Ago And Far Away 10,000 Maniacs When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Bésame mucho (English Vocal) Because The Night 'S Wonderful For Me And My Gal 10CC 1930s Standards 'Til Then Dreadlock Holiday Let's Call The Whole Thing Off Daddy's Little Girl I'm Not In Love Heartaches The Old Lamplighter The Things We Do For Love Cheek To Cheek Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Rubber Bullets Love Is Sweeping The Country That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Life Is A Minestrone My Romance That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) 112 It's Time To Say Aloha I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Cupid We Gather Together Aren't You Glad You're You Peaches And Cream Kumbaya (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 12 Gauge The Last Time I Saw Paris My One And Only Highland Fling Dunkie Butt All The Things You Are No Love No Nothin' 12 Stones Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Personality Far Away Begin The Beguine Sunday, Monday Or Always Crash I Love A Parade This Heart Of Mine 1800s Standards I Love A Parade (short version) Mister Meadowlark Home Sweet Home I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter 1950s Standards Home On The Range Body And Soul Get Me To The Church On