Cracker Etiquette: Stories from Somebody's South by Philip Booth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exploration of Family History Through Autobiography and Record Analysis by Anna Peabody a THESIS Su

The Stories We Will Tell: An Exploration of Family History through Autobiography and Record Analysis by Anna Peabody A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Marketing (Honors Scholar) Presented June 1, 2017 Commencement June 2017 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Anna Peabody for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Marketing presented on June 1, 2017. Title: The Stories We Will Tell: An Exploration of Family History Through Autobiography and Record Analysis. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Thomas Bahde The research of genealogy and family history can represent a means of self- discovery, connection, and preservation of the past. The experience is individualistic, unique to the intricate intertwining of lives that helped create and influence who we are today. Through the analysis of historical biographies, family documents, and autobiographical vignettes, I explore the significance of general and personal family history portrayed in a narrative writing style. Studying texts that utilize styles and record analysis to tell untold stories of figures in history, including Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past: Power and Production of History, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s A Midwife’s Tale, and Richard White’s Remembering Ahanagran, I am provided the tools necessary to tell my own silenced history. The following sections of the text will explore that history of each of my four major lineages, combining the tools learned from the researched texts with records compiled for genealogical purposes to construct a narrative for a living document. My own reflections and historical context are used to orient the narrative and give meaning to the chronological events of the past that aligned to tell my story. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Karaoke Version Song Book

Karaoke Version Songs by Artist Karaoke Shack Song Books Title DiscID Title DiscID (Hed) Planet Earth 50 Cent Blackout KVD-29484 In Da Club KVD-12410 Other Side KVD-29955 A Fine Frenzy £1 Fish Man Almost Lover KVD-19809 One Pound Fish KVD-42513 Ashes And Wine KVD-44399 10000 Maniacs Near To You KVD-38544 Because The Night KVD-11395 A$AP Rocky & Skrillex & Birdy Nam Nam (Duet) 10CC Wild For The Night (Explicit) KVD-43188 I'm Not In Love KVD-13798 Wild For The Night (Explicit) (R) KVD-43188 Things We Do For Love KVD-31793 AaRON 1930s Standards U-Turn (Lili) KVD-13097 Santa Claus Is Coming To Town KVD-41041 Aaron Goodvin 1940s Standards Lonely Drum KVD-53640 I'll Be Home For Christmas KVD-26862 Aaron Lewis Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow KVD-26867 That Ain't Country KVD-51936 Old Lamplighter KVD-32784 Aaron Watson 1950's Standard Outta Style KVD-55022 An Affair To Remember KVD-34148 That Look KVD-50535 1950s Standards ABBA Crawdad Song KVD-25657 Gimme Gimme Gimme KVD-09159 It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas KVD-24881 My Love, My Life KVD-39233 1950s Standards (Male) One Man, One Woman KVD-39228 I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus KVD-29934 Under Attack KVD-20693 1960s Standard (Female) Way Old Friends Do KVD-32498 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31474 When All Is Said And Done KVD-30097 1960s Standard (Male) When I Kissed The Teacher KVD-17525 We Need A Little Christmas KVD-31475 ABBA (Duet) 1970s Standards He Is Your Brother KVD-20508 After You've Gone KVD-27684 ABC 2Pac & Digital Underground When Smokey Sings KVD-27958 I Get Around KVD-29046 AC-DC 2Pac & Dr. -

Fulton Daily Leader, April 5, 1947 Fulton Daily Leader

Murray State's Digital Commons Fulton Daily Leader Newspapers 4-5-1947 Fulton Daily Leader, April 5, 1947 Fulton Daily Leader Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/fdl Recommended Citation Fulton Daily Leader, "Fulton Daily Leader, April 5, 1947" (1947). Fulton Daily Leader. 628. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/fdl/628 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fulton Daily Leader by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •, y • V. • $ te-r 1 The Weather ril 4,1947 Kentucky -Considerable clou- MEMBER iness and windy with thunder- this means showers tonight, becoming cold- natty friends er in west portion; Sunda K TUCKY PRES clearing, windy and heir kindness colder. LAII1t011 ASSOCIATION tees and wh- ritaitr r TAibAn SIO• ir father. We Volume thank Rev NLVIlt Associated Presa Leased Wire Fulton, Iradley, Dr. Kentucky, °Stunt-du) t.renitut. Iprii .3. /9/7 re Cents Per Copy id their staff =Mb Ann Horn- Lewis Asks U. S. Burlington Roy Wright. Rural Co-Op, Zephyr Smacks Into Station -• Jo Leave (?nly 2 Chinese Reds h p', Marines les Green. easeminim-i; K.U. Told To 1..'oal Mines Open. ,to Vi'ashington, April 5-4,Th Pi 110111111g 11:0"(d Aear Tangku; Accept -John I.. Lewis today asked Union the government today asked NLRB Says but two bituminous coal • Roth miiies in the United States. iRiolrest Toll Since End of War I In a letter to colt mines Ilful Refused To administrator N. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

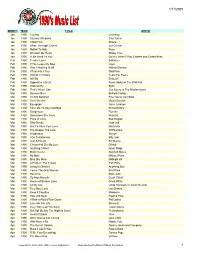

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

The Hidden Child VOL

The Hidden Child VOL. XXIII 2015 PUBLISHED BY HIDDEN CHILD FOUNDATION®/ADL AS IF IT WERE Two young children, one wearing a yellow star, play on a street in the Lodz ghetto, 1943. The little YESTERDAY girl is Ilona Winograd, born in January 1940. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Ilona Winograd-Barkal. AS IF IT WERE YESTERDAY A JEWISH CHILD IN CHRISTIAN DISGUISE WHEN WE WERE YOUNG AND 9 EXTRAORDINARILY GUTSY: THE MAKING OF THE FILM COMME SI C’ÉTAIT HIER (AS IF IT WERE YESTERDAY) (1980) THE SEARCH FOR PRISONER 1002: RICHARD BRAHMER By Nancy Lefenfeld 14 One summer day in 1976, while on a heavily on Myriam’s mother, Léa; she asked visit to Brussels, Myriam Abramowicz found her daughter to visit Mrs. Ruyts and extend herself sitting in a kitchen chair, staring at the family’s condolences. AVRUMELE’S WARTIME MEMOIR the back of the woman who had hidden her Myriam had been born in Brussels short- 18 parents during the German Occupation. It ly after the end of the war and had spent was four in the afternoon—time for goûter— her early childhood there. When she was and Nana Ruyts was preparing a tray of six years old and a student at the Lycée TRAUMA IN THE YOUNGEST sweets to serve to her guest. Describing Carter, there was, in Myriam’s words, “an HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS the moment nearly forty years later, Myri- incident.” “In the courtyard during recess, 26 am ran an index finger over the curve that a little girl by the name of Monique—her lay at the base of her skull and spoke of father was our butcher—called me a sale the vulnerability of this part of the human Juif, a dirty Jew, and I hit her, and then my LA CASA DI SCIESOPOLI: ‘THE HOUSE’ anatomy. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 08/09/2016 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 08/09/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Crazy - Patsy Cline Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Don't Stop Believing - Journey Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Shake It Off - Taylor Swift Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond My Girl - The Temptations Like I'm Gonna Lose You - Meghan Trainor Girl Crush - Little Big Town Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Ex's & Oh's - Elle King Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Let It Go - Idina Menzel Me Too - Meghan Trainor Baby Got Back - Sir Mix-a-Lot EXPLICIT Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals H.O.L.Y. - Florida Georgia Line Hello - Adele Sweet Home Alabama - Lynyrd Skynyrd When We Were Young - Adele Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Jackson - Johnny Cash Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Summer Nights - Grease Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Unchained Melody - The Righteous Brothers Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Stop The Feeling - Justin Timberlake Piano Man - Billy Joel I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys All Of Me - John Legend Turn The Page - Bob Seger These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley My Way - Frank Sinatra (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Love Shack - The B-52's 7 Years - Lukas Graham Wannabe - Spice Girls A Whole New World - -

DJ Master Mix CD List

DJ Master Mix CD List ***Background Music*** 25 Gloria in Excelsis Deo (vocal) 2 Pennsylvania 6-5000 3 Chatanooga Choo-Choo 101 Strings Play Frank Sinatra ***Background Music*** 4 String of pearls 1 All the way 25 All Time Christmas Favorites Di 5 In the mood 2 Strangers in the night 1 Jingle bells (pop) 6 Sunrise serenade 3 Fly me to the moon 2 Joy to the world (pop) 7 Johnson rag 4 New York, New York 3 Deck the halls (pop) 8 American patrol 5 The lady is a tramp 4 We wish you a merry Christmas (pop) 9 Kalamazoo 6 Come fly with me 5 Hark the herald angels sing (pop) 10 Bugle call rag 7 I've got you under my skin 6 Jolly old St. Nicholas (pop) 11 Anvil chorus 8 Young at heart 7 O Christmas Tree (pop) 12 Tuxedo junction 9 Just the way you look tonight 8 Auld Lang Syne (pop) 13 Moonlight cocktail 10 You're nobody till somebody loves you 9 The twelve days of Christmas(pop) 14 Serenade in blue 11 The shadow of your smile 10 We three Kings (pop) 12 Three coins in the fountain 11 Ave Maria (vocal) ***Background Music*** ***Background Music*** 12 Gloria a Jesu(vocal) Big Band Spectacular Vol. II 13 Alleluia (vocal) 1 One O'clock jump 15 of the World's Greatest Love Son 14 II Est Ne Le Divin Enfant 2 Jersey bounce 1 Wind beneath my wings 15 Silver Bells (vocal) 3 Frankie and Johnny were lovers 2 Always on my mind 16 Alleluiah 4 Stomping at the Savoy 3 All out of love 17 For unto us a child is born 5 Down south camp meeting 4 Dust in the wind 18 The trumpet shall sound 6 Jumping at the woodside 5 Lady in red 19 Amen 7 Let's dance 6 Up where we -

An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases Translated by Michael D

久須本文雄 Kusumoto Bun’yū (1907-1995) 禅語入門 Zengo nyūmon Tokyo: 大法輪閣 Daihōrin-kaku Co. Ltd., 1982 An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases Translated by Michael D. Ruymar (Michael Sōru Ruymar) 1 What follows is a translation of Kusumoto Bunyū’s (久須本⽂雄) 1982 book Zengo Nyūmon (禅 語⼊⾨, An Introduction to Zen Words and Phrases, Tokyo: Daihōrin-kaku Co. Ltd.), absent its glossary of monastic terms. The main text consists of 100 words and phrases selected by Dr. Kusumoto for exegesis from a variety of sources, but particularly from classic kōan (Zen case) collections like the Blue Cliff Record, the Gateless Barrier, and the Book of Serenity, as well as from the collected writings or sayings of renowned Zen Masters from both China and Japan, like Zen Masters Linji and Dōgen, or, again, from the poetry of such as Han Shan (Cold Mountain) and others. As a genre, there are numerous books of this kind available in Japan, and I have become familiar with two excellent Zengo texts now available to English readers: (i) Moon by The Window: The calligraphy and Zen insights of Shodo Harada (Wisdom Publications, 2011), !and (ii) Zen Words Zen Calligraphy (Tankosha, 1991). It is evident from the breadth and depth of his commentaries that Dr. Kusumoto brought a lifetime of study to bear on the matter contained herein. Though sketchy, he was born in 1908 and graduated in 1933 from what is now Hanazono University, one of several prestigious institutions at which he was destined to lecture in his areas of specialization: Chinese philosophy and Zen studies. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 25/10/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 25/10/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Wannabe - Spice Girls Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond Zombie - The Cranberries I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor Don't Stop Believing - Journey Dancing Queen - ABBA Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Perfect - Ed Sheeran Piano Man - Billy Joel Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Africa - Toto Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Black Velvet - Alannah Myles Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Santeria - Sublime Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Someone Like You - Adele Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Valerie - Amy Winehouse Livin' On A Prayer - Bon Jovi Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker New York, New York - Frank Sinatra Girl Crush - Little Big Town House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals What A Wonderful World - Louis Armstrong Summer Nights - Grease Jackson - Johnny Cash Jolene - Dolly Parton Crazy - Patsy Cline Let It Go - Idina Menzel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding My Girl - The Temptations All Of Me - John Legend I Wanna Dance With Somebody - Whitney Houston Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Turn The Page - Bob Seger Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn My Way - Frank Sinatra These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter I Want It That Way - Backstreet