Forests of Mount Rainier National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellowstone National Park, Resources and Issues, Vegetation

VEGETATION More than 1,300 plant taxa occur in Yellowstone National Park. The whitebark pine, shown here and found in high elevations in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, is an important native species in decline. Vegetation The vegetation communities of Yellowstone National major disturbances. Yellowstone is home to three Park include overlapping combinations of species endemic plant species, at least two of which depend typical of the Rocky Mountains as well as of the on the unusual habitat created by the park’s thermal Great Plains to the east and the Intermountain region features. Most vegetation management in the park to the west. The exact vegetation community pres- is focused on minimizing human-caused impacts on ent in any area of the park reflects the consequences their native plant communities to the extent feasible. of the underlying geology, ongoing climate change, substrates and soils, and disturbances created by fire, Vegetation Communities floods, landslides, blowdowns, insect infestations, There are several vegetation communities in and the arrival of nonnative plants. Yellowstone: higher- and lower-elevation forests Today, the roughly 1,386 native taxa in the park and the understory vegetation associated with them, represent the species able to either persist in the area sagebrush-steppe, wetlands, and hydrothermal. or recolonize after glaciers, lava flows, and other Quick Facts Number in Yellowstone • Three endemic species (found only Management Issues Native plant taxa: more than 1,300: in Yellowstone): Ross’s bentgrass, • Controlling nonnative species, • Hundreds of wildfowers. Yellowstone sand verbena, which threaten native species, Yellowstone sulfur wild buckwheat. especially near developed areas; • Trees: nine conifers (lodgepole some are spreading into the Nonnative plant species: 225. -

Scientific Name Species Common Name Abies Lasiocarpa FIR Subalpine Acacia Macracantha ACACIA Long-Spine

Scientific Name Species Common Name Abies lasiocarpa FIR Subalpine Acacia macracantha ACACIA Long-spine Acacia roemeriana CATCLAW Roemer Acer grandidentatum MAPLE Canyon Acer nigrum MAPLE Black Acer platanoides MAPLE Norway Acer saccharinum MAPLE Silver Aesculus pavia BUCKEYE Red Aesculus sylvatica BUCKEYE Painted Ailanthus altissima AILANTHUS Tree-of-heaven Albizia julibrissin SILKTREE Mimosa Albizia lebbek LEBBEK Lebbek Alnus iridis ssp. sinuata ALDER Sitka Alnus maritima ALDER Seaside Alvaradoa amorphoides ALVARADOA Mexican Amelanchier laevis SERVICEBERRY Allegheny Amyris balsamifera TORCHWOOD Balsam Annona squamosa SUGAR-APPLE NA Araucaria cunninghamii ARAUCARIA Cunningham Arctostaphylos glauca MANZANITA Bigberry Asimina obovata PAWPAW Bigflower Bourreria radula STRONGBACK Rough Brasiliopuntia brasiliensis PRICKLY-PEAR Brazilian Bursera simaruba GUMBO-LIMBO NA Caesalpinia pulcherrima FLOWERFENCE NA Capparis flexuosa CAPERTREE Limber CRUCIFIXION- Castela emoryi THORN NA Casuarina equisetifolia CASUARINA Horsetail Ceanothus arboreus CEANOTHUS Feltleaf Ceanothus spinosus CEANOTHUS Greenbark Celtis lindheimeri HACKBERRY Lindheimer Celtis occidentalis HACKBERRY Common Cephalanthus occidentalis BUTTONBUSH Common Cercis canadensis REDBUD Eastern Cercocarpus traskiae CERCOCARPUS Catalina Chrysophyllum oliviforme SATINLEAF NA Citharexylum berlandieri FIDDLEWOOD Berlandier Citrus aurantifolia LIME NA Citrus sinensis ORANGE Orange Coccoloba uvifera SEAGRAPE NA Colubrina arborescens COLUBRINA Coffee Colubrina cubensis COLUBRINA Cuba Condalia globosa -

Guide Alaska Trees

x5 Aá24ftL GUIDE TO ALASKA TREES %r\ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE Agriculture Handbook No. 472 GUIDE TO ALASKA TREES by Leslie A. Viereck, Principal Plant Ecologist Institute of Northern Forestry Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station ÜSDA Forest Service, Fairbanks, Alaska and Elbert L. Little, Jr., Chief Dendrologist Timber Management Research USD A Forest Service, Washington, D.C. Agriculture Handbook No. 472 Supersedes Agriculture Handbook No. 5 Pocket Guide to Alaska Trees United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Washington, D.C. December 1974 VIERECK, LESLIE A., and LITTLE, ELBERT L., JR. 1974. Guide to Alaska trees. U.S. Dep. Agrie., Agrie. Handb. 472, 98 p. Alaska's native trees, 32 species, are described in nontechnical terms and illustrated by drawings for identification. Six species of shrubs rarely reaching tree size are mentioned briefly. There are notes on occurrence and uses, also small maps showing distribution within the State. Keys are provided for both summer and winter, and the sum- mary of the vegetation has a map. This new Guide supersedes *Tocket Guide to Alaska Trees'' (1950) and is condensed and slightly revised from ''Alaska Trees and Shrubs" (1972) by the same authors. OXFORD: 174 (798). KEY WORDS: trees (Alaska) ; Alaska (trees). Library of Congress Catalog Card Number î 74—600104 Cover: Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis)., the State tree and largest in Alaska, also one of the most valuable. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402—Price $1.35 Stock Number 0100-03308 11 CONTENTS Page List of species iii Introduction 1 Studies of Alaska trees 2 Plan 2 Acknowledgments [ 3 Statistical summary . -

Site Basic Report 7/11/2006

Site Basic Report 7/11/2006 Site Code BCD S.USIDHP*688 Site Class Standard site Name DOME LAKE Defining Managed Area DOME LAKE RNA State/Province Idaho Directions Dome Lake RNA lies at the northern end of the Bighorn Crags in the Salmon River Mountains, about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of the Salmon River, at a point about 17 miles (27.5 km) southwest of Shoup. | Access to the RNA is possible via several routes, none of which are quick and easy. One route follows: From the town of North Fork, head west on the Salmon River Road 033 for about 36 miles (58 km). The western trailhead for FS Trail 172 is on the south side of the Salmon River between river miles 201 and 202 (opposite of Colson Creek RNA), just west of the junction with FS Road 123 (Colson Creek Road). From the trailhead, FS Trail 172 heads south, switchbacking up the ridge west of Shell Creek and gaining about 5000 feet (1524 m) in elevation over about three air miles (4.8 km) as it climbs to an area just below the Horse Heaven Lookout. Just southeast of the lookout, FS Trail 172 joins the ridgeline that defines the western boundary of the RNA. Other routes include FS Trail 021 from Crags Campground, approximately a 10 mile hike (16 km), and the eastern trailhead of 172 which leaves from near the junction of the Salmon River Road 033 and Panther Creek Road 055. Minimum Elevation: 4,700 Feet 1,433 Meters Maximum Elevation: 9,316 Feet 2,840 Meters Site Description Dome Lake RNA contains the entire upper portion of the Lake Creek watershed. -

SC Trees & Shrubs

Alaska Department of Natural Resources / Division of Forestry / Community Forestry Program 550 W. 7th Ave., Ste. 1450 / Anchorage, AK 99501 / 269-8466 / http://forestry.alaska.gov/community Trees & Shrubs for South Central Alaska The following trees and shrubs are growing successfully in south central Alaska. Each has specific requirements and should be planted where conditions and space allow it to be healthy and safe. For a complete list of plants, descriptions, limitations, requirements, and hardiness, see www.alaskaplants.org. For information on selecting and planting trees, see http://forestry.alaska.gov/community/publications.htm. Deciduous Trees Acer glabrum var. douglasii – Douglas maple Acer negundo – Boxelder Acer platanoides – Norway maple Acer rubrum – Red maple Acer tataricum var. ginnala – Amur maple Betula papyrifera – Paper birch Betula pendula – European white birch Crataegus – Hawthorn Fraxinus manshurica – Manchurian ash Fraxinus nigra – Black ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica – Green ash Larix – Larch, tamarack Malus – Apple, crabapple Populus balsamifera – Balsam poplar Populus tremula – Swedish columnar aspen Populus tremuloides, Aspen Populus trichocarpa – Cottonwood Prunus cerasus ‘Evans’ – Cherry Prunus maackii – Amur chokecherry Prunus pennsylvanica – Pin cherry Pyrus ussuriensis – Ussurian pear Quercus macrocarpa – Bur oak Sorbus aucuparia – Mountainash Syringa reticulata – Japanese tree lilac Tilia Americana – American linden, basswood Tilia cordata - Littleleaf linden Evergreen Tree Abies concolor – White fir Abies -

TREES AS CROPS in ALASKA PROFILE with an EMPHASIS on SPRUCE Revised 2009

TREES AS CROPS IN ALASKA PROFILE WITH AN EMPHASIS ON SPRUCE Revised 2009 Robert A. Wheeler Thomas R. Jahns Janice I. Chumley PRODUCTION FACTS Growing trees in Alaska can be difficult. This document addresses basic questions regarding growing tree seedlings as an agricultural crop. Whether growing a few seedlings or thousands, many of the basic production questions are the same. From the standpoint of tree seedling production there are three basic regions in Alaska: Southeast, South Central, and the Interior. Producing high quality tree seedlings is 4-H Tree Sale in Soldotna, AK May 2003 achievable in all three regions however care must (photo/Bob Wheeler). be taken to match tree species requirements with local environmental conditions. Through the efforts of the University of Alaska Fairbanks and the Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station, many tree species have been evaluated over the past 100 years for their performance. Results from these species trials have led to the listing of tree species, growth characteristics, and site requirements found in Table 1. DEMAND Interest in tree production can vary from growing trees for your yard or property to full scale outdoor or greenhouse, bareroot, or container nurseries. Tree planting and tree sales continue to be of considerable interest to the public although there are no large-scale commercial tree nurseries currently operating in Alaska. A state tree nursery was once operated in the Matanuska Valley area, but it has been closed. Reasons for the closure were based upon the high cost of producing seedlings in Alaska versus what it would cost to import them from nurseries outside the state and also, the overall operational difficulties and risks associated with an Alaska nursery program. -

Subalpine Fir (Bl)- Abies Lasiocarpa

Subalpine fir (Bl)- Abies lasiocarpa Tree Species > Subalpine fir Page Index Distribution Range and Amplitiudes Tolerances and Damaging Agents Silvical Characteristics Genetics and Notes BC Distribution of Subalpine fir (Bl) Range of Subalpine fir Old-growth, subalpine fir stands cover a large area of the ESSF zone, particularly in wetter areas, such as northwest of Smithers Geographic Range and Ecological Amplitudes Description Subalpine fir is a medium - to large-sized (exceptionally >40 m tall), evergreen conifer, at maturity with a low-taper stem, narrow, dense, cylindrical crown, with a spire-like top, short, drooping branches, and grayish-brown bark, breaking into irregular scales with age. Its light, soft, odorless wood is used mainly for lumber. Geographic Range Geographic element: Western North American/mainly Cordilleran and less Pacific Distribution in Western North America: (central) in the Pacific region; north, central, and south in the Cordilleran region Ecological Amplitudes Climatic amplitude: (alpine tundra) - continental subalpine boreal - montane boreal - (cool temperate) Orographic amplitude: montane - subalpine - (alpine) Occurrence in biogeoclimatic zones: (lower AT), submaritime MH, SWB, ESSF, MS, (BWBS), SBS, (upper IDF), upper ICH, (wetter submaritime CWH) Subalpine fir grows mainly in humid, continental boreal climates, with a short growing season; less frequently in cool temperate climates, with a longer growing season. When these climates become drier and/or warmer, subalpine fir is absent or its occurrence is rare (e.g., in the SBPS and PP zones). Edaphic Amplitude Range of soil moisture regimes: (moderately dry) - slightly dry - fresh - moist - very moist - wet Range of soil nutrient regimes: very poor - poor - medium - rich - very rich Field studies indicate that subalpine fir is most vigorous on moist and rich sites, with calcium - and magnesium-rich soils such as those derived from basaltic or limestone parent materials. -

Examples of Forest Habitat Types in Montana

EXAMPLES OF FOREST HABITAT TYPES IN MONTANA Published as part of Forest Habitat Types of Montana, 1977 USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Ogden, Utah (This group of images was presented as a poster in the printed version of this document.) Pinus flexilislAgropyron spica tum h .t. Dry, rocky W. slope (4,900 ft) near Whitehall supporting Pinus Ilexilis, Juniperus scopulorum, and scattered Pseudotsuga. Pseudorsuga menziesiil Vaccinium globulare h. t. (Arctostaphylos phase) S. exposure (4,700 ft) in a relatively most area of west-central Montana. Seral Pinus ponderosa is an overstory dominant; Vaccinium and Xerophyllum dominate the undergrowth. Pinus ponderosa1A ropyron spicatum h.t. Steep SW. slope (4,500 ft) near Missoula. ?inusponderosa is a long-lived seral dominant. Pseudotsuga menziesii ILinnaea borealis h.t. (Symphoricarpos phase) Valley bottom (2,600 It) in NW. Montana. Larix occidentalis is the dominant seral tree. Pinus ponderosal Prunus virginiana h. t . (Prunus phase) Lower N. slope (4,000 ft) near Ashland. Prunus has been browsed back by deer. Pseudotsu a menziesiilSymphoricarpos albus h.t. (Calamagrostis p$I ase) W. slope (7,050 ft) in south-central Montana. Pseudotsuga is dominant in all size classes. Undergrowth is dominated by symphoricarP6s, Calamagrostis, and Carex geyeri, with numerous forbs. Pseudo tsuga menziesiilA#rop yron spica tum h .t . Steep S. slope(5,650 ft) in west-central ontana Soil is loose and gravelly; much of ground surface is exposed, partly because of grazing. Pseudo tsuga menziesiiICalamagros tis rubescens h.t. (Calamagrostis phase) SE. slope (6,300 ft) in west-central Montana. Typical park-like stand of old-growthPseudotsuga, with dense mat of Calamagrostis and Arnica cordifolia beneath. -

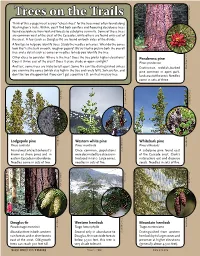

Trees on the Trails D Think of This 4-Page Insert As Your “Cheat Sheet” for the Trees Most Often Found Along Washington’S Trails

trees canreach 300feettall. east of the crest. Old-growth forests drier in and forests rain western both in tree Abundant Pseudotsuga menziesii Douglas-fir Needles comeinsetsoftwo. abundance. in Cascades eastern known as shore pine) and in it’s (where crest of west Found Pinus contorta pine Lodgepole WASHINGTON WASHINGTON don’t betoodisappointedifyoucan’tgetapositiveI.D.onthatmysterytree. and fun, have So fall!). rarely and tree the in high stay (which cones the examine you unless distinguished be can’t firs Some apart. tell to tricky are trees some last, And Does itthriveeastofthecrest?craveshadeoropensunlight? elevations? higher prefer tree the Does tree? the is Where consider: to clues Other overall the both picture tree andadetailsuchasconesorneedlestohelpyouidentifythetree. to tried We’ve papery? or rough smooth, bark the Is like? look cones the do What leaves. or needles the Study trees: identify you help to tips few A the crest.Afew(suchasDouglas-fir)arefoundonbothsidesofdivide. of east only found are others while Cascades, the of crest the of west common are trees these of Some summits. subalpine to forests lowland from everywhere found trees deciduous flowering and conifers both find along you’ll Within, found trails. often Washington’s most trees the for sheet” “cheat your as insert 4-page this of Think Trees ontheTrails Trees TRAILS ALAN BAUER ALAN BAUER DAVE SCHIEFELBEIN ALAN BAUER very shadetolerant. below 3,500 feet, this tree is forests westside in Douglas-fir Second only in abundance to heterophylla Tsuga hemlock Western needles insetsoffive. cones, Large 1910. in troduced in disease a by decimated were Once common, populations Pinus monticola pine white Western August 2007 August - SUSAN MCDOUGAL SUSAN MCDOUGAL SYLVIA FEDER SUSAN MCDOUGAL come insetsofthree. -

Sixth International Christmas Tree Research & Extension

Sixth International Christmas Tree Research & Extension Conference September 14 - 19, 2003 Kanuga Conference Center Hendersonville, NC Proceedings Hosted by North Carolina State University CONFERENCE SPONSORS Cellfor Inc. Mitchell County Christmas Tree Growers and Nurserymen's Association Avery County East Carolina University – Christmas Tree & Nurserymen's Association Department of Biology Monsanto – Makers of Roundup Agricultural Herbicides North Carolina State University – Ashe County Christmas Tree Association Christmas Tree Genetics Program College of Natural Resources North Carolina Christmas Tree Association Eastern North Carolina Christmas Tree Association North Carolina Forest Service Avery County Cooperative Extension Service Center and Master Gardeners North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Christmas Tree Council of Nova Scotia Proceedings of the 6th International Christmas Tree Research & Extension Conference September 14 - 19, 2003 Kanuga Conference Center Hendersonville, NC Hosted by North Carolina State University John Frampton, Organizer and Editor Forward During September 2003, North Carolina State University hosted the 6th International Christmas Tree Research and Extension Conference. This conference was the latest in the following sequence: Date Host Organization Location Country October Washington State Puyallup, USA 1987 University Washington August Oregon State Corvallis, Oregon USA 1989 University October Silver Fall State Silver Falls, Oregon USA 1992 Park September Cowichan Lake Mesachie Lake, Canada 1997 Research Station British Columbia July/August Danish Forest and Vissenbjerg Denmark 2000 Landscape Research Institute The conference started September 14th with indoor presentations and posters at the Kanuga Conference Center, Hendersonville, N.C., and ended September 18th in Boone following a 1½ day field trip. The conference provided a forum for the exchange of scientific research results concerning various aspects of Christmas tree production and marketing. -

Status and Dynamics of Whitebark Pine (Pinus Albicaulis Engelm.) Forests in Southwest Montana, Central Idaho, and Oregon, U.S.A

Status and Dynamics of Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis Engelm.) Forests in Southwest Montana, Central Idaho, and Oregon, U.S.A. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Evan Reed Larson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Kurt F. Kipfmueller June 2009 © Evan Reed Larson 2009 Acknowledgements This research was made possible through the efforts of a number of people. For their help in the field, my thanks go to Kyle Anderson, Adam Berland, Brad Bogard, Neil Green-Clancey, Noelle Harden, Zack and Mesa Holmboe, Matt Jacobson, Eric and Shelley Larson, Tony and Donna Praza, Danica and Mara Larson, Karen Arabas, Joe Bowersox, and the Forest Ecology class from Willamette University including Eric Autrey, Luke Barron, Jeff Bennett, Laura Cattrall, Maureen Goltz, Whitney Pryce, Maria Savoca, Hannah Wells, and Kaitlyn Wright. Thanks to Jessica Burke, Noelle Harden, and Jens Loberg for their long hours helping sand my samples to a high shine. Many thanks also to USDA Forest Service personnel Carol Aubrey, Kristen Chadwick, Vickey Erickson, Carly Gibson, Bill Given, Robert Gump, Chris Jensen, Bob Keane, Al Kyles, Clark Lucas, Robin Shoal, David Swanson, Sweyn Wall, and Bob Wooley for their time and assistance in planning logistics and gaining sampling permission for my research. I am fortunate to have been influenced by many wonderful friends and mentors during my academic career. I give thanks to my Ph.D. committee members Lee Frelich, Kathy Klink, Bryan Shuman, and Susy Ziegler for their guidance and efforts on my behalf. -

Evaluation of Needle Nutritional Status in a Nordmann Fir Christmas Tree

Proceedings of the 8. international christmas tree research & extension conference Thomsen, Iben Margrete; Rasmussen, Hanne Nina; Sørensen, Johanne Margrethe Møller Publication date: 2008 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Thomsen, I. M., Rasmussen, H. N., & Sørensen, J. M. M. (Eds.) (2008). Proceedings of the 8. international christmas tree research & extension conference Forest & Landscape, University of Copenhagen. Download date: 09. okt.. 2021 Proceedings of the 8th International Christmas Tree Research & Extension Conference FOREST & LANDSCAPE WORKING PAPERS 26 / 2008 By Iben M. Thomsen, Hanne N. Rasmussen & Johanne M. Sørensen (Eds.) Title Proceedings of the 8th International Christmas Tree Research & Extension Conference IUFRO Working Unit 2.02.09 - Christmas Trees Hotel Bogense Kyst, Denmark, August 12th - 18th, 2007 Held by Forest & Landscape Denmark and Danish Christmas Tree Growers’ Association Editors Iben Margrete Thomsen Hanne N. Rasmussen Johanne Møller Sørensen Publisher Forest & Landscape Denmark University of Copenhagen Hørsholm Kongevej 11 DK-2970 Hørsholm Tel. +45 3533 1500 [email protected] Series-title and no. Forest & Landscape Working Papers no. 26-2008 published on www.SL.life.ku.dk also available at www.ps-xmastree.dk and www.iufro.org ISBN 978-87-7903-342-9 Citation Thomsen, I.M., Rasmussen, H.N. & Sørensen, J.M. (Eds.) 2008: Proceedings of the 8th International Christmas Tree Research and Extension Conference. Forest & Landscape Working Papers No. 26- 2008, 145 pp. Forest & Landscape Denmark, Hørsholm. Citation allowed with clear source indication Written permission is required if you wish to use Forest & Landscape’s name and/or any part of this report for sales and advertising purposes.