Analysis of Godard's Pierrot Le

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Géo-Politique De L'image Dans Les Histoire(S) Du Cinéma De Jean-Luc

La Géo-politique de l’image dans les Histoire(s) du cinéma de Jean-Luc Godard1 Junji Hori Les Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–98) de Jean-Luc Godard s’offre comme un collage kaléidoscopique d’innombrables fragments de films et d’actualités. Nous pouvons cependant tout de suite constater que la plupart des fragments appartiennent au cinéma occidental d’avant la Nouvelle Vague. L’inventaire de films cités contient aussi peu d’œuvres contemporaines que venant d’Asie et du tiers-monde. Mais cet eurocentrisme manifeste des Histoire(s) n’a curieusement pas fait l’objet d’attentions spéciales, et ce malgré la prospérité intellectuelle des Études culturelles et du post- colonialisme dans le monde anglo-américain des années 90. Il arrive certes que certains chercheurs occidentaux mentionnent brièvement le manque de référence au cinéma japonais dans l’encyclopédie de Godard, mais il n’y a que très peu de recherches qui sont véritablement consacrées à ce sujet. Nous trouvons toutefois une critique acharnée contre l’eurocentrisme des Histoire(s) dans un article intitulé Ç Pacchoro » de Inuhiko Yomota. Celui-ci signale que les films cités par Godard fournissent un panorama très imparfait par rapport à la situation actuelle du cinéma mondial et que ses choix s’appuient sur une nostalgie toute personnelle et un eurocentrisme conscient. Les Histoire(s) font abstraction du développement cinémato- graphique d’aujourd’hui de l’Asie de l’Est, de l’Inde et de l’Islam et ainsi manquent- elles de révérence envers les autres civilisations. Il reproche finalement à l’ironiste Godard sa vie casanière en l’opposant à l’attitude accueillante de l’humoriste Nam Jun Paik2. -

Of Christophe Honoré: New Wave Legacies and New Directions in French Auteur Cinema

SEC 7 (2) pp. 135–148 © Intellect Ltd 2010 Studies in European Cinema Volume 7 Number 2 © Intellect Ltd 2010. Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/seci.7.2.135_1 ISABELLE VANDERSCHELDEN Manchester Metropolitan University The ‘beautiful people’ of Christophe Honoré: New Wave legacies and new directions in French auteur cinema ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Drawing on current debates on the legacy of the New Wave on its 50th anniversary French cinema and the impact that it still retains on artistic creation and auteur cinema in France auteur cinema today, this article discusses three recent films of the independent director Christophe French New Wave Honoré: Dans Paris (2006), Les Chansons d’amour/Love Songs (2007) and La legacies Belle personne (2008). These films are identified as a ‘Parisian trilogy’ that overtly Christophe Honoré makes reference and pays tribute to New Wave films’ motifs and iconography, while musical offering a modern take on the representation of today’s youth in its modernity. Study- adaptation ing Honoré’s auteurist approach to film-making reveals that the legacy of the French Paris New Wave can elicit and inspire the personal style and themes of the auteur-director, and at the same time, it highlights the anchoring of his films in the Paris of today. Far from paying a mere tribute to the films that he loves, Honoré draws life out his cinephilic heritage and thus redefines the notion of French (European?) auteur cinema for the twenty-first century. 135 December 7, 2010 12:33 Intellect/SEC Page-135 SEC-7-2-Finals Isabelle Vanderschelden 1Alltranslationsfrom Christophe Honoré is an independent film-maker who emerged after 2000 and French sources are mine unless otherwise who has overtly acknowledged the heritage of the New Wave as formative in indicated. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 27 Dresses DVD-8204 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 28 Days Later DVD-4333 10th Victim DVD-5591 DVD-6187 12 DVD-1200 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 12 and Holding DVD-5110 3 Women DVD-4850 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 12 Monkeys DVD-3375 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 1776 DVD-0397 300 DVD-6064 1900 DVD-4443 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 1984 (Hurt) DVD-4640 39 Steps DVD-0337 DVD-6795 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 1984 (Obrien) DVD-6971 400 Blows DVD-0336 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 42 DVD-5254 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 50 First Dates DVD-4486 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 500 Years Later DVD-5438 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-0260 61 DVD-4523 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 70's DVD-0418 2012 DVD-4759 7th Voyage of Sinbad DVD-4166 2012 (Blu-Ray) DVD-7622 8 1/2 DVD-3832 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 8 Mile DVD-1639 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 9 to 5 DVD-2063 25th Hour DVD-2291 9.99 DVD-5662 9/1/2015 9th Company DVD-1383 Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet DVD-0831 A.I. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Film Itself As the Story: Reflexive Constructions in Alfred Hitchcock and Jean-Luc Godard

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Film No Longer Telling a Story; Film Itself as the Story: Reflexive Constructions in Alfred Hitchcock and Jean-Luc Godard Amy Ertie Chabassier Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Film Production Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Philosophy of Language Commons, Theory and Criticism Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Chabassier, Amy Ertie, "Film No Longer Telling a Story; Film Itself as the Story: Reflexive Constructions in Alfred Hitchcock and Jean-Luc Godard" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 219. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/219 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Film no Longer Telling a Story; Film itself as the Story: Reflexive Constructions in Alfred Hitchcock and Jean-Luc Godard Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Arts of Bard College by Amy Chabassier Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to singularly thank one of many from the film department, Peter Hutton, for his introducing me to the Bolex, for his landscapes, and for his recurring inspiration. -

Wide Angle a Journal of Literature and Film

Wide Angle a journal of literature and film Volume 8, Issue 1 Fall 2018 Published by Department of English Samford University 3 Mission Statement Literature and film continually reimagine an ever-changing world, and through our research we discover our relationships to those art forms and the cultures they manifest. Publishing one issue each semester, Wide Angle serves as a conduit for the expression and critique of that imagination. A joint publication between English majors and faculty, the journal embodies the interdisciplinary nature of the Department of English at Samford University. It provides a venue for undergraduate research, an opportunity for English majors to gain experience in the business of editing and publishing, and a forum for all students, faculty, and staff to publish their best work. As a wide-angle lens captures a broad field of vision, this journal expands its focus to include critical and creative works, namely academic essays, book and film reviews, and commentaries, as well as original poetry, short fiction and non-fiction, and screenplays. Editorial Staff 2018-‘19 Managing Editor……………………Hannah Warrick Assistant Managing Editor…………Emily Youree Literature Editor…………………....Claire Davis Film Editor………………………....Annie Brown Creative Writing Editor…………….Regan Green General Editor……………………...Dr. Geoffrey A. Wright Copyright © 2018 Wide Angle, Samford University. All rights reserved. Wide Angle 8.1 4 Contents Literature “Love’s a Drag: Reconciling Gender, Sexuality, and Attraction in Sonnet 20” Jillian Fantin……………………………………………………………………………………6 -

300 Greatest Films 4 Black Copy

The goal in this compilation was to determine film history's definitive creme de la creme. The titles considered to be the greatest of the great from around the world and throughout the history of film. So, after an in-depth analysis of respected critics and publications from around the globe, cross-referenced and tweaked to arrive at the ranking of films representing, we believe, the greatest cinema can offer. Browse, contemplate, and enjoy. Check off all the films you have seen 1 Citizen Kane 1941 USA 26 The 400 Blows 1959 France 51 Au Hasard Balthazar 1966 France 76 L.A. Confidential 1997 USA 2 Vertigo 1958 USA 27 Satantango 1994 Hungary 52 Andrei Rublev 1966 USSR 77 Modern Times 1936 USA 3 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 UK 28 Raging Bull 1980 USA 53 All About Eve 1950 USA 78 Mr Hulot's Holiday 1952 France 4 The Rules of the Game 1939 France 29 L'Atalante 1934 France 54 Sunset Boulevard 1950 USA 79 Wings of Desire 1978 France 5 Seven Samurai 1954 Japan 30 Annie Hall 1977 USA 55 The Turin Horse 2011 Hungary 80 Ikiru 1952 Japan 6 The Godfather 1972 USA 31 Persona 1966 Sweden 56 Jules and Jim 1962 France 81 The Apartment 1960 USA 7 Apocalypse Now 1979 USA 32 Man With a Movie Camera 1929 USSR 57 Double Indemnity 1944 USA 82 Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie 1972 France 8 Tokyo Story 1953 Japan 33 E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 1982 USA 58 Contempt (Le Mepris) 1963 France 83 The Seventh Seal 1957 Sweden 9 Taxi Driver 1976 USA 34 Star Wars Episode IV 1977 USA 59 Belle De Jour 1967 France 84 Wild Strawberries 1957 Sweden 10 Casablanca 1942 USA 35 -

The Point in Time: Precise Chronology in Early Godard

First published in Studies in French Cinema 3:2 (2003), 101-109 The point in time: precise chronology in early Godard ‘A film is out of date when it doesn’t give a true picture of the era it was made in’, said Godard in 1960 (Godard 1972: 26), and in 1966: ‘All of my films report on the situation of the country, are documents d’actualité’1 (Godard 1971: 12). My subject here is the actuality of the documents we see and hear in Godard’s sixties’ films, the truth of the picture given. Godard has a reputation for having kept pace with his time, a reputation founded in the 1960s,2 when his films held a mirror up to the ephemeral detritus of the real and said it was beautiful. Neon signs, film posters, records on the jukebox, magazine covers…: the film of these passing phenomena celebrates them, and documents them in their place and time. The mirror image implies a certain passivity, and here I wish to illustrate how the reflective function of Godard’s films is an active engagement with his time, in fact a critical revision of what it means to be ‘of’ a time. Serge Daney comments, somewhere, that Godard was the first to put in a fiction film the newspaper of the day of the shoot (Bergala 1999: 225). Daney may have forgotten the scene in Paris nous appartient (Rivette, 1961), filmed at the beginning of September 1958, where we see the front page of L’Equipe, with the headline announcing Ercole Baldini’s victory in cycling’s World Road Championship the day before.3 Then again, the newspaper is in the hand of Godard himself, cycling fan and extra in Rivette’s film, and we can at least say that from the outset he was associated with this cinematic use of found materials. -

Tasevska EF 2020 Final

Etudes Francophones Vol. 32 Printemps 2020 Bande dessinée et intermédialité Godard’s Contra-Bande: Early Comic Heroes in Pierrot le fou and Le Livre d’image Tamara Tasevska Northwestern University Introduction Throughout Jean-Luc Godard’s scope of work spanning over more than six decades, references to the comic strip strangely surface, seemingly unattached to any interpretative frame, creating instability and disproportion within the form of the films. Specific images of characters reading and performing Les Pieds Nickelés, or Zig et Puce appear in his early films, À Bout de souffle (1960), Une Femme est une femme (1961) and Pierrot le fou (1965), whereas in Une femme est une femme (1960), Alphaville (1965), Made in U.S.A (1966), and Tout va bien (1972), the whole of the diegetic world resembles the compositions and frames of the comic strip. In Godard’s later period, even though we witness an acute shift in register of the image, comic figures ostensibly continue to appear, drained of color, as if photocopied several times, floating free in a void of empty black space detached from any definitive meaning. Without doubt, the filmmaker uses the comic strip as Brechtian means in order to provoke distanciation effects (Sterritt 64), but I would also suggest that these instances put forward by the comic may also function to point to provocative connections between aesthetics and politics.1 Thinking of Godard’s oeuvre, in the chapter “Au-delà de l’image-mouvement” of L’image-temps, Gilles Deleuze remarks that the filmmaker drew inspiration from the comic strip at its most cruel and cutting, thus constructing a world according to “émouvantes” and “terribles” images that reach a level of autonomy in and of themselves (18-19). -

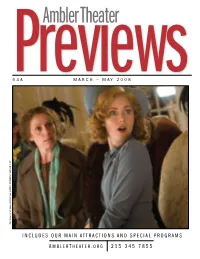

Includes Our Main Attractions

Ambler Theater Previews63A MARCH – MAY 2008 Amy Adams and Frances McDormand in MISS PETTIGREW LIVES FOR A DAY Adams and Frances McDormand in MISS PETTIGREW LIVES FOR Amy INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS A MBLERT HEATER.ORG 215 345 7855 Welcome to the nonprofit Ambler Theater The Ambler Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. ADMISSION Give us Feedback Your film experience is the most important thing to us, so we welcome your feedback. Please let us know what we can do General ............................................................$8.50 better. Call (215) 345-7855, or email us at Members .........................................................$4.50* [email protected] Seniors (62+) Children under 18 and When will films play? Students w/valid I.D. .....................................$6.50 Matinee (before 5:30 pm) ...............................$6.50 Main Attractions Wed Early Matinee (before 2:30 pm) ...............$5.00 Film Booking. Our main films play week-to-week from Friday Affiliated Theaters Members** .........................$5.50 through Thursday. Every Monday we determine what new films will start on Friday, what current films will end on Thursday, **Affiliated Theaters Members and what current films will continue through Friday for another The Ambler Theater, the County Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film In- week. All films are subject to this week-to-week decision-mak- ing process. We try to play all of our Main Attraction films as stitute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your Ambler membership soon as possible. (For more info on the business of booking will allow you $5.50 admission at the other theaters. (You must films and why some films play longer or sooner than others, present your membership card to obtain this discount.) visit our website.) Be a Member When Will a Film’s Run Start? Become a member of the nonprofit Ambler Theater and show your After we decide on Monday (Tuesday at the latest) what new support for good films and a cultural landmark. -

Lectures Et Voix Littéraires Dans Pierrot Le Fou, De Jean-Luc Godard

PASCAL VACH ER Lectures et voix littéraires dans Pierrot le fou, de Jean-Luc Godard ierrot le fou, l’un des films phares de Jean-Luc Godard, est, davantage encore Pque ses autres créations, émaillé de références littéraires. Et, de façon assez unique dans le cinéma de Godard, celles-ci relèvent moins de l’allusion que de la citation directe du texte sur le mode de la lecture à haute voix. Pourquoi cette propension à la lecture de textes littéraires véhiculés par les voix des protagonistes ? Comment analyser ces lectures qui confèrent à Pierrot le fou sa tonalité unique dans l’histoire du cinéma ? Nous ne nous intéresserons pas ici à la façon dont les textes lus sont en rapport avec la situation. Il est, par exemple, évident que le poème de Robert Browning cité par Ferdinand (Jean-Paul Belmondo) illustre parfaitement la situation du couple que ce dernier forme avec Marianne (Anna Karina), de même que « L’Éternité » de Rimbaud intervient à point nommé lorsque les deux héros ne sont plus de ce monde et que la caméra fixe le bleu du ciel. Au-delà d ’une fonction illustrative, la littérature, justement parce que les textes sont lus, acquiert une place essentielle dans Pierrot le fou. Quelle place précisément, avec quelles conséquences sur notre réception de spectateur ? C’est ce que nous allons tenter de cerner. Mais avant toute chose, se pose la question : comment reconnaît-on la lecture dans un film ? Contrairement à ce que l’on pourrait croire de prime abord, ce n’est pas là une question simple. -

Newsletter Été 2009

Bulletin Culturel July - August 2009 focus DJ Medhi The Cinematheque Ontario presents The New Wave UNIVERSAL CODE EXHIBITION AT THE POWER PLANT Gabriel Orozco, Black Kites Perspective Summer paths lead you through meadows, marshlands and marches. Get rid of the astrolab, forget about GPS, whatever the compass : in such a mess, where is Contents the satellite bending over ? Time spend to cook is pure happiness. During harsh winter, Amélie Nothomb PAGE 4 - Festival shared with us her admiration for her sister Juliette’s recipes : « to please me, PAGE 5 - Exhibitions [she] cooks up, with a lot of humor, theorically freakish dishes, at the end I enjoy PAGE 6 - Theater them so much. Green tea chesnut spread is my favorite, but overall, sweet tooth obliged, is the Mont Fuji cake which remembers me about my descent… »* PAGE 7 - Music Power Plant invites artists dealing with beginnings to end mysteries, the Cine- PAGE 9 - Cinema matheque offers on-going images’ feast. DJ Medhi and M83 go electro. Joël Savary, Attaché Culturel * « La cuisine d’Amélie, 80 recettes de derrière les fagots » by Juliette Nothomb. July 2009 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12 3 4 5 CINEMA CINEMA CINEMA - A woman is a - Alphaville The Nun woman - Jules and Jim - Breathless 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 CINEMA CINEMA CINEMA The sign of Leo Pierrot le fou - To live her life - And God created woman 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 CINEMA CINEMA CINEMA THEATER THEATER - Band of Out- Les bonnes Bob le flam- Je serais tou- Je serais tou- siders femmes beur jours là ..