The Case of the Sama-Bajau of Maritime Southeast Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

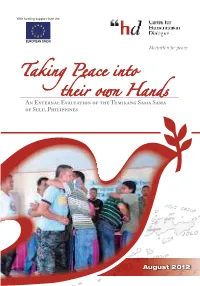

Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands

Taking Peace into An External Evaluation of the Tumikang Sama Sama of Sulu, Philippinestheir own Hands August 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre) would like to thank the author of this report, Marides Gardiola, for spending time in Sulu with our local partners and helping us capture the hidden narratives of their triumphs and challenges at mediating clan confl icts. The HD Centre would also like to thank those who have contributed to this evaluation during the focused group discussions and interviews in Zamboanga and Sulu. Our gratitude also goes to Mary Louise Castillo who edited the report, Merlie B. Mendoza for interviewing and writing the profi le of the 5 women mediators featured here, and most especially to the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines, headed by His Excellency Ambassador Guy Ledoux, for believing in the power of local suluanons in resolving their own confl icts. Lastly, our admiration goes to the Tausugs for believing in the transformative power of dialogue. DISCLAIMER This publication is based on the independent evaluation commissioned by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue with funding support from the Delegation of the European Union in the Philippines. The claims and assertions in the report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the HD Centre nor of the Eurpean Union. COVER “Taking Peace Into Their Own Hands” expresses how people in the midst of confl ict have taken it upon themselves to transform their situation and usher in relative peace. The cover photo captures the culmination of the mediation process facilitated by the Tumikang Sama Sama along with its partners from the Provincial Government, the Municipal Governments of Panglima Estino and Kalinggalan Caluang, the police and the Marines. -

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: a Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution

Ethnic and Religious Conflict in Southern Philippines: A Discourse on Self-Determination, Political Autonomy, and Conflict Resolution Jamail A. Kamlian Professor of History at Mindanao State University- ILigan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT), ILigan City, Philippines ABSTRACT Filipina kini menghadapi masalah serius terkait populasi mioniritas agama dan etnis. Bangsa Moro yang merupakan salah satu etnis minoritas telah lama berjuang untuk mendapatkan hak untuk self-determination. Perjuangan mereka dilancarkan dalam berbagai bentuk, mulai dari parlemen hingga perjuangan bersenjata dengan tuntutan otonomi politik atau negara Islam teroisah. Pemberontakan etnis ini telah mengakar dalam sejarah panjang penindasan sejak era kolonial. Jika pemberontakan yang kini masih berlangsung itu tidak segera teratasi, keamanan nasional Filipina dapat dipastikan terancam. Tulisan ini memaparkan latar belakang historis dan demografis gerakan pemisahan diri yang dilancarkan Bangsa Moro. Setelah memahami latar belakang konflik, mekanisme resolusi konflik lantas diajukan dalam tulisan ini. Kata-Kata Kunci: Bangsa Moro, latar belakang sejarah, ekonomi politik, resolusi konflik. The Philippines is now seriously confronted with problems related to their ethnic and religious minority populations. The Bangsamoro (Muslim Filipinos) people, one of these minority groups, have been struggling for their right to self-determination. Their struggle has taken several forms ranging from parliamentary to armed struggle with a major demand of a regional political autonomy or separate Islamic State. The Bangsamoro rebellion is a deep- rooted problem with strong historical underpinnings that can be traced as far back as the colonial era. It has persisted up to the present and may continue to persist as well as threaten the national security of the Republic of the Philippines unless appropriate solutions can be put in place and accepted by the various stakeholders of peace and development. -

A Study of the Badjaos in Tawi- Tawi, Southwest Philippines Erwin Rapiz Navarro

Centre for Peace Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education Living by the Day: A Study of the Badjaos in Tawi- Tawi, Southwest Philippines Erwin Rapiz Navarro Master’s thesis in Peace and Conflict Transformation – November 2015 i Abstract This study examines the impacts of sedentarization processes to the Badjaos in Tawi-Tawi, southwest of the Philippines. The study focuses on the means of sedentarizing the Badjaos, which are; the housing program and conditional cash transfer fund system. This study looks into the conditionalities, perceptions and experiences of the Badjaos who are beneficiaries of the mentioned programs. To realize this objective, this study draws on six qualitative interviews matching with participant-observation in three different localities in Tawi-Tawi. Furthermore, as a conceptual tool of analysis, the study uses sedentarization, social change, human development and ethnic identity. The study findings reveal the variety of outcomes and perceptions of each program among the informants. The housing project has made little impact to the welfare of the natives of the region. Furthermore, the housing project failed to provide security and consideration of cultural needs of the supposedly beneficiaries; Badjaos. On the other hand, cash transfer fund, though mired by irregularities, to some extent, helped in the subsistence of the Badjaos. Furthermore, contentment, as an antithesis to poverty, was being highlighted in the process of sedentarization as an expression of ethnic identity. Analytically, this study brings substantiation on the impacts of assimilation policies to indigenous groups, such as the Badjaos. Furthermore, this study serves as a springboard for the upcoming researchers in the noticeably lack of literature in the study of social change brought by sedentarization and development policies to ethnic groups in the Philippines. -

Dr Mahathir's

OPPORTUNITY MALAYSIA 2018 Malaysia and Singapore Neighbours & Partners in Growth A SPECIAL PUBLICATION BY THE HIGH COMMISSION OF MALAYSIA, SINGAPORE OPPORTUNITY MALAYSIA 2018 Photo credits: CONTENTS Malaysian High Commission in Singapore Department of Information, Malaysia Singapore Ministry of Foreign Affairs Singapore Ministry of Communication & Information 01 Editor’s Note ASEAN Secretariat 02 Message from the High Commission of Malaysia, Singapore 03 Introducing the New High Commissioner BILATERAL TIES 04 Dr Mahathir’s Return to Singapore 06 Prime Ministers Highlight the Importance of Bilateral Ties 04 08 The TUN Experience 10 At the 33rd ASEAN Summit FEATURE 12 Special Conferment Ceremony ECONOMY 16 The ASEAN Business & Investment Summit: The Fight Against Protectionism 20 ARTS & CULTURE 20 Causeway EXChange: Arts & Healing Festival TOURISM 24 2019 Visit Melaka Year 25 See You in Sarawak 25 EDITOR’S NOTE Engaging at All Levels PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF elcome to the 2018 edition of Nomita Dhar Opportunity Malaysia. We, for many EDITORIAL years in collaboration and support from Ranee Sahaney High Commission of Malaysia, have been Prionka Ray Wputting together this annual publication. Arjun Dhar Malaysia and Singapore being close neighbours are engaged on multiple levels. Each day people from DESIGN Syed Jaafar Alkaff the two countries work or move across the borders, to visit relatives, make a living, savour their favourite ADVERTISING delights etc. To ensure the smoothness of our ties, & MARKETING the two countries must cooperate and engage at so Swati Singh many different levels and many government agencies collaborate and communicate with each other on a PHOTOS High Commission of Malaysia, daily basis to this end. -

1 Orang Asli and Melayu Relations

1 Orang Asli and Melayu Relations: A Cross-Border Perspective (paper presented to the Second International Symposium of Jurnal Antropologi Indonesia, Padang, July 18-21, 2001) By Leonard Y. Andaya In present-day Malaysia the dominant ethnicity is the Melayu (Malay), followed numerically by the Chinese and the Indians. A very small percentage comprises a group of separate ethnicities that have been clustered together by a Malaysian government statute of 1960 under the generalized name of Orang Asli (the Original People). Among the “Orang Asli” themselves, however, they apply names usually associated with their specific area or by the generalized name meaning “human being”. In the literature the Orang Asli are divided into three groups: The Semang or Negrito, the Senoi, and the Orang Asli Melayu.1 Among the “Orang Asli”, however, the major distinction is between themselves and the outside world, and they would very likely second the sentiments of the Orang Asli and Orang Laut (Sea People) in Johor who regard themselves as “leaves of the same tree”.2 Today the Semang live in the coastal foothills and inland river valleys of Perak, interior Pahang, and Ulu (upriver) Kelantan, and rarely occupy lands above 1000 meters in elevation. But in the early twentieth century, Schebesta commented that the areas regarded as Negrito country included lands from Chaiya and Ulu Patani (Singora and Patthalung) to Kedah and to mid-Perak and northern Pahang.3 Most now live on the fringes rather than in the deep jungle itself, and maintain links with Malay farmers and Chinese shopkeepers. In the past they appear to have also frequented the coasts. -

Covid-19 Conditional Movement Control Order (Cmco) in Malaysia Frequently Asked Questions

COVID-19 CONDITIONAL MOVEMENT CONTROL ORDER (CMCO) IN MALAYSIA FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS S/N Question Answer Leaving Malaysia 1 The Malaysian government Under the CMCO, some restrictions of the MCO have been eased, has implemented a such as allowing the re-opening of certain businesses and Conditional Movement resumption of the economic sector. Singaporeans in Malaysia will Control Order (CMCO) still be allowed to leave during the CMCO period. However, since 4 May. What is the Singaporeans should be prepared for significant travel CMCO, and will inconveniences due to the travel restrictions. Singaporeans will not Singaporeans be allowed be able to re-enter Malaysia during the CMCO period. to leave Malaysia? 2 Will airports, flights, and Based on the current available information, airports and land land checkpoints remain checkpoints* will continue to operate during the CMCO period. open during the CMCO There are limited direct flights to Singapore from KLIA and KLIA2. period? Those leaving Malaysia are advised to plan their own transport arrangements and check directly with transport operators for any changes/cancellations. [*Operating hours at the Bangunan Sultan Iskandar checkpoint in Johor Bahru is 7am to 7pm daily.] 3 [UPDATED] I am a According to the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, foreign Singaporean and I intend nationals who wish to return to their respective countries are to return to Singapore. Am required to comply with the following procedures: I allowed to travel across states to KL International a) Possess valid travel documents including passport and Airport (KLIA) / Causeway / airline ticket; and Second Link? b) Obtain written concurrence from the respective Diplomatic Missions. -

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, Dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1

Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 MUNICIPALITIES Classification NCR 1. Pateros 1st CAR ABRA 1 Baay-Licuan 5th 2 Bangued 1st 3 Boliney 5th 4 Bucay 5th 5 Bucloc 6th 6 Daguioman 5th 7 Danglas 5th 8 Dolores 5th 9 La Paz 5th 10 Lacub 5th 11 Lagangilang 5th 12 Lagayan 5th 13 Langiden 5th 14 Luba 5th 15 Malibcong 5th 16 Manabo 5th 17 Penarrubia 6th 18 Pidigan 5th 19 Pilar 5th 20 Sallapadan 5th 21 San Isidro 5th 22 San Juan 5th 23 San Quintin 5th 24 Tayum 5th 25 Tineg 2nd 26 Tubo 4th 27 Villaviciosa 5th APAYAO 1 Calanasan 1st 2 Conner 2nd 3 Flora 3rd 4 Kabugao 1st 5 Luna 2nd 6 Pudtol 4th 7 Sta. Marcela 4th BENGUET 1. Atok 4th 2. Bakun 3rd 3. Bokod 4th 4. Buguias 3rd 5. Itogon 1st 6. Kabayan 4th 7. Kapangan 4th 8. Kibungan 4th 9. La Trinidad 1st 10. Mankayan 1st 11. Sablan 5th 12. Tuba 1st blgf/ltod/updated 1 of 30 updated 4-27-16 Income Classification Per DOF Order No. 23-08, dated July 29, 2008 13. Tublay 5th IFUGAO 1 Aguinaldo 2nd 2 Alfonso Lista 3rd 3 Asipulo 5th 4 Banaue 4th 5 Hingyon 5th 6 Hungduan 4th 7 Kiangan 4th 8 Lagawe 4th 9 Lamut 4th 10 Mayoyao 4th 11 Tinoc 4th KALINGA 1. Balbalan 3rd 2. Lubuagan 4th 3. Pasil 5th 4. Pinukpuk 1st 5. Rizal 4th 6. Tanudan 4th 7. Tinglayan 4th MOUNTAIN PROVINCE 1. Barlig 5th 2. Bauko 4th 3. Besao 5th 4. -

A Plan to Manage the Fisheries of Tawi- Tawi Marine Key Biodiversity

INTER-LGU FISHERIES MANAGEMENT PLAN A Plan to Manage the Fisheries of Tawi- Tawi Marine Key Biodiversity Area Applying the Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management Covering the Municipalities of: Bongao Panglima Sugala Sapa- Sapa Simunul South Ubian Tandubas December 2016 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Site – Location, Boundaries and Basic Features 1.2 Plan – Rationale, Objectives, Guiding Principles, Planning Process and Contents 2. Profile of Tawi-Tawi MKBA 2.1. Key Ecological Features: Weather, Meteorology, Season; Oceanographic Characteristics, Marine & Coastal Habitats 2.2. Key Socio-Economic Features: Population and Basic Demography, Post-Harvest, Market Infrastructure, Occupation, Income and Poverty 2.3. Key Institutional Features/Fisheries Governance: 2.3.1 Overview of Relevant Laws, Regulations, Policies 2.3.2 Jurisdictional Boundaries 2.3.3 Organizations/Institutions Involved in Fisheries Managemen 2.3.4 Programs/Projects related to Fisheries and Coastal Resource Management 2.3.5 EAFM Benchmarks for LGUs 2.4. Fisheries in Focus: Gears, Efforts, including Gear Distribution, Catch and Trends 3. Issues/Problems and Opportunities 3.1 Ecological Dimensions 3.2 Socio-Economic Dimensions 3.3 Governance Dimensions 4. Priority Action Plans and Programs 4.1 Inter-LGU/MKBA-Wide Management Actions 4.1.1. Inter-LGU Alliance: Tawi-Tawi MKBA Alliance MPA Network, CLE, FM Plans 4.1.2. Delineation of Municipal Boundaries and Zoning 4.1.3. Economic Incentives 5. Adoption and Implementation of the Plan 5.1 Adoption of the Plan 5.2 Financing the Plan 6. Monitoring and Evaluation 7. Reference Cited and/or Consulted 8. Attachments 8.1 Results of EAFM-Benchmarking of Focal LGUs in 2013, 2014 8.2 Perceived Changes in Fisheries Resources in the Past 20 Years 8.3 Changes in Coral Cover and Fish Biomass as Monitores from 2004-2010 8.4 Individual LGU Priority Actions Plans 1- INTRODUCTION 1.1 Site Tawi-Tawi is an archipelagic and the southernmost province of the Philippines in the Sulu Archipelago bordering on Sabah, East Malaysia. -

The Vulnerability of Bajau Laut (Sama Dilaut) Children in Sabah, Malaysia

A position paper on: The vulnerability of Bajau Laut (Sama Dilaut) children in Sabah, Malaysia Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN) 888/12, 3rd Floor Mahatun Plaza, Ploenchit Road Lumpini, Pratumwan 10330 Bangkok, Thailand Tel: +66(0)2-252-6654 Fax: +66(0)2-689-6205 Website: www.aprrn.org The vulnerability of Bajau Laut (Sama Dilaut) children in Sabah, Malaysia March 2015 Background Statelessness is a global man-made phenomenon, variously affecting entire communities, new-born babies, children, couples and older people, and can occur because of a bewildering array of causes. According to UNHCR, at least 10 million people worldwide have no nationality. While stateless people are entitled to human rights under international law, without a nationality, they often face barriers that prevent them from accessing their rights. These include the right to establish a legal residence, travel, work in the formal economy, access education, access basic health services, purchase or own property, vote, hold elected office, and enjoy the protection and security of a country. The Bajau Laut (who often self-identify as Sama Dilaut and are referred to by others as ‘Pala’uh’) are arguably some of the most marginalised people in Malaysia. Despite records of their presence in the region dating back for centuries, today many Bajau Laut have no legal nationality documents bonding them to a State, are highly vulnerable to exploitation and abuse. The Bajau Laut are a classic example of a protracted and intergenerational statelessness situation. Children, the majority of whom were born in Sabah and have never set foot in another country, are particularly at risk. -

Sulu Archipelago

AMERICAN MUSEUM Novitates PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10024 Number 2818, pp. 1-32, figs. 1-19, tables 1-5 June 11, 1985 Philippine Rattus: A New Species from the Sulu Archipelago GUY G. MUSSER1 AND LAWRENCE R. HEANEY2 ABSTRACT A new species, Rattus tawitawiensis, is de- close relative now living in either the Philippine scribed from Tawitawi Island in the southern Sulu Islands to the east or on the islands and peninsula Islands. It is native to the island, whereas Rattus ofthe Sunda Shelfto the west. In morphology, the rattus mindanensis, which also occurs there is not. Tawitawi rat is most similar to species of Rattus The known mammalian fauna of the Sulu Archi- living on islands rimming the Sunda Shelfbeyond pelago has characteristics indicating that the is- the 180 m bathymetric line. These peripheral iso- lands have had no recent land-bridge connection lates appear to be most similar to Rattus tio- to either Borneo or Mindanao; this is consistent manicus among the extant fauna ofthe Sunda Shelf. with geological evidence. The new species has no INTRODUCTION From September 1971 to January 1972, those species in this report. Two of them, R. members of the Delaware Museum of Nat- exulans and R. rattus mindanensis, are prob- ural History and Mindanao State University ably not native to the Sulu Archipelago. The Expedition collected vertebrates in the South third species, represented by three specimens Sulu Islands (fig. 1). A report of that expe- from Tawitawi Island, is new and endemic dition has been provided by duPont and Ra- to the Sulu Archipelago. -

Chapter 5 Existing Conditions of Flood and Disaster Management in Bangsamoro

Comprehensive capacity development project for the Bangsamoro Final Report Chapter 5. Existing Conditions of Flood and Disaster Management in Bangsamoro CHAPTER 5 EXISTING CONDITIONS OF FLOOD AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT IN BANGSAMORO 5.1 Floods and Other Disasters in Bangsamoro 5.1.1 Floods (1) Disaster reports of OCD-ARMM The Office of Civil Defense (OCD)-ARMM prepares disaster reports for every disaster event, and submits them to the OCD Central Office. However, historic statistic data have not been compiled yet as only in 2013 the report template was drafted by the OCD Central Office. OCD-ARMM started to prepare disaster reports of the main land provinces in 2014, following the draft template. Its satellite office in Zamboanga prepares disaster reports of the island provinces and submits them directly to the Central Office. Table 5.1 is a summary of the disaster reports for three flood events in 2014. Unfortunately, there is no disaster event record of the island provinces in the reports for the reason mentioned above. According to staff of OCD-ARMM, main disasters in the Region are flood and landslide, and the two mainland provinces, Maguindanao and Lanao Del Sur are more susceptible to disasters than the three island provinces, Sulu, Balisan and Tawi-Tawi. Table 5.1 Summary of Disaster Reports of OCD-ARMM for Three Flood Events Affected Damage to houses Agricultural Disaster Event Affected Municipalities Casualties Note people and infrastructures loss Mamasapano, Datu Salibo, Shariff Saydona1, Datu Piang1, Sultan sa State of Calamity was Flood in Barongis, Rajah Buayan1, Datu Abdulah PHP 43 million 32,001 declared for Maguindanao Sangki, Mother Kabuntalan, Northern 1 dead, 8,303 ha affected. -

Trade in the Sulu Archipelago: Informal Economies Amidst Maritime Security Challenges

1 TRADE IN THE SULU ARCHIPELAGO: INFORMAL ECONOMIES AMIDST MARITIME SECURITY CHALLENGES The report Trade in the Sulu Archipelago: Informal Economies Amidst Maritime Security Challenges is produced for the X-Border Local Research Network by The Asia Foundation’s Philippine office and regional Conflict and Fragility unit. The project was led by Starjoan Villanueva, with Kathline Anne Tolosa and Nathan Shea. Local research was coordinated by Wahida Abdullah and her team at Gagandilan Mindanao Women Inc. All photos featured in this report were taken by the Gagandilan research team. Layout and map design are by Elzemiek Zinkstok. The X-Border Local Research Network—a partnership between The Asia Foundation, Carnegie Middle East Center and Rift Valley Institute—is funded by UK aid from the UK government. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this report are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of The Asia Foundation or the UK Government. Published by The Asia Foundation, October 2019 Suggested citation: The Asia Foundation. 2019. Trade in the Sulu Archipelago: Informal Economies Amidst Maritime Security Challenges. San Francisco: The Asia Foundation Front page image: Badjao community, Municipality of Panglima Tahil, Sulu THE X-BORDER LOCAL RESEARCH NETWORK In Asia, the Middle East and Africa, conflict and instability endure in contested border regions where local tensions connect with regional and global dynamics. With the establishment of the X-Border Local Research Network, The Asia Foundation, the Carnegie Middle East Center, the Rift Valley Institute and their local research partners are working together to improve our understanding of political, economic and social dynamics in the conflict-affected borderlands of Asia, the Middle East and the Horn of Africa, and the flows of people, goods and ideas that connect them.