Classical Poets of Gujarat.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

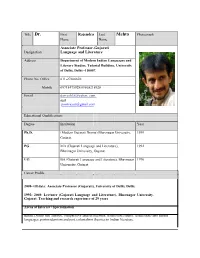

Dr Rajendra Mehta.Pdf

Title Dr. First Rajendra Last Mehta Photograph Name Name Associate Professor-Gujarati Designation Language and Literature Address Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, Tutorial Building, University of Delhi, Delhi -110007. Phone No Office 011-27666626 Mobile 09718475928/09868218928 Email darvesh18@yahoo. com and [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. (Modern Gujarati Drama) Bhavnagar University, 1999 Gujarat. PG MA (Gujarati Language and Literature), 1992 Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. UG BA (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar 1990 University, Gujarat. Career Profile 2008- till date: Associate Professor (Gujarati), University of Delhi, Delhi. 1992- 2008: Lecturer (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. Teaching and research experience of 29 years Areas of Interest / Specialization Indian Drama and Theatre, comparative Indian literature, translation studies, translations into Indian languages, postmodernism and post colonialism theories in Indian literature. Subjects Taught 1- Gujarati language courses (certificate, diploma, advanced diploma) 2-M.A (Comparative Indian Literature) Theory of literary influence, Tragedy in Indian literature, Ascetics and poetics 3-M.Phil (Comparative Indian Literature): Gandhi in Indian literature. Introduction to an Indian language- Gujarati Research Guidance M.Phil. student -12 Ph.D. student - 05 Details of the Training Programmes attended: Name of the Programme From Date To Date Duration Organizing Institution -

M.Phil. Gujarati

SAURASHTRA UNIVERSITY RAJKOT (ACCREDITED GRADE “A” BY NAAC) FACULTY OF GUJARATI Syllabus for M. Phil. (GUJARATI) Choice Based Credit System With Effect From: 2016-17 Programme Outcomes PO1 : The student will be leaning towards the society, a sense of humanity, love and cosmopolitanism will be cultivated in them. PO2 : Students will be awakened towards the abundance of knowledge that is deepening in the 21st century and their professional readiness will be refined. PO3 : The study of language and literature, the realization of how the student can be a link by becoming a strong medium to nurture human consciousness and the spirit of human unity. PO4 : The student will understand the glory of the mother-tongue and will feel respect and pride towards the mother-tongue in his heart. Programme Specific Outcomes of M.Phil. Gujarati PSO1 : Students will receive knowledge about research methodology and comparative approach. PSO2 : The student can study and experience about fieldwork. PSO3 : The student can understand the difference between criticism and research. PSO4 : The student will can understand the Tradition and new trends of Gujarati Criticism. 1 M.Phil. Semester – 1 – CCT - 01 Research Methodology Duration No. Weightage Weightage of of For Subject Title of the Cource For Total Semester Hrs. Semester Code Course Credits Internal Markes End Per End Examination Exam in Week Examination Hrs. CCT-01 - Research 4 4 30 70 100 2.5 1601010103010100 Methodology Course Outcomes CCT - 01 Research Methodology CO1 The purpose and form of research can be studied. CO2 Student can study the scope of research and the differences between research and Criticism. -

Rasa and Garba in the Arts of Gujarat 1

Rasa and Garba in the Arts of Gujarat 1 Jyotindra Jain Rasa and garba are two interrelated and exceedingly popular forms of dance in Gujarat. The purpose of this article is not so much to trace the general chronology of rasa and garba from literary evidence as to examine the local Gujarati varieties of these dance forms in relation to their plastic and pictorial depictions. Literary sources, however graphic in description, do not always provide an accurate picture of the visual aspects of dance. Therefore rasa and garba as depicted in the visual arts of Gujarat might serve as a guide to an understanding of some features of these dances otherwise not easy to construe. Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan2 has given a sufficiently exhaustive and analytical account of rasa as described in the Harivamsha, Vishnu Purana, Shrimad Bhagavata and Brahma Vaivarta Purana as well as the commentaries of Nilakantha on the Puranas. Vasant Yamadagni3 and Ramanarayana Agrawal4 have published full-fledged monographs on the rasaleela of Vraja and other related subjects. The aspects covered by them will not be dealt with in this article. The descriptions of rasa in the Puranas make it clear that it is a circle-dance in which the participants move with hands interlocked. It appears that rasa included several types of circle-dances: ( 1) Those where several gopi-s formed a circle with Krishna in the centre; 5 (2) Those where Radha and Krishna danced as a pair together with other gopi-s or other pairs of gopa-s and gopi-s;6 (3) Those where Krishna multiplied himself and actually danced between two gopi-s thus forming a ring with one gopi and one Krishna. -

![Dr. Ushaben G. Upadhyay [Professor].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3643/dr-ushaben-g-upadhyay-professor-pdf-3213643.webp)

Dr. Ushaben G. Upadhyay [Professor].Pdf

Curriculum Vitae Name : Prof. Dr. Usha Upadhyay Date of Birth : 07/06/1956 Address (Postal) : 14, fourth floor, Vandemataram Arcade, Vandemataram Cross, Road, New Gota, Ahmedabad‐ 382481 Current Position : Professor and Head, Department of Gujarati, M.D. Samajsewa Sankul, Gujarat Vidyapith, Ahmedabad – 380014 E‐mail : [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mobile : +91‐9426415887, 9106305995 1 Academic Qualifications Division / Exam Grade / Board/University Subjects Year passed Merit. Ph. D. Saurashtra Uni., Rajkot Symbols in Post‐ 1982 Awarded Independence Gujarati Poetry M.A. S.N.D.T. Uni., Mumbai Gujarati 1977 55% B.A. S.N.D.T. Uni., Mumbai Main‐Gujarati, 1975 56% Sub‐Hindi Contribution to Teaching Courses Taught Name of University/College/Institution Duration M.A., M. Phil, Department of Gujarati, Gujarat Vidyapith, 1998 to till date Ph.D. (PG) Ahmedabad M.A. (PG) Department of Gujarati, Bhavnagar Uni., Bhavnagar 1990 to 1998 M.A. (PG) N.P. Arts College,Keshod 1987 to 1990 K.O. Shah College, Dhoraji B.A. (UG) M.M.G. Mahila College, Junagadh 1985 to 1990 Area of Specialization 1. Comparative Literature 2. Folk Literature 3. Indian Poetics 4. Women’s Studies 2 Awards and other Achievements Awards: 1. Late Bhagirathibahen Maheta (Jahnvi) Smriti Kavyitri Award, Shishuvihar, Bhavnagar, 2018 2. ‘Nari‐Shakti’ Award, Palitana, 2017 3. ‘Women Achiever’s Award by Udgam Institute, Gandhinagar, 2015 4. ‘Sahitya Darshan’ Samaan by Kendriy Hindi Sansthan, Agra, 2014 5. ‘Nagrik Samman’ by Municipal Corporation, Ahmedabad, 2013 6. ‘Mahatma Savitribai Phule’ Award by Mahatma Savitribai Phule Talent Research Academy, Nagpur, 2012 7. -

The Perception of the Literary Tradition of Gujarat in the Late Nineteenth Century

1 ■Article■ The Perception of the Literary Tradition of Gujarat in the Late Nineteenth Century ● Riho Isaka I The late nineteenth century saw the rise of interest in the develop- ment of vernacular literature among Indian intellectuals educated under the colonial system. Gujarat was no exception, and active debates arose among the literati on the question of defining the 'correct' language , creating 'new' literature and understanding their literary tradition . The aim of this paper is to examine how the Gujarati intellectuals of this period articulated their literary tradition, and what influence this articu- lation had on the social and cultural life of this region in the long term . It attempts to show how these literati, in describing this tradition , selec- tively appropriated ideas and idioms introduced under colonial rule as well as those existing in the local society from the pre-British period , according to their needs and circumstances. By the time British rule began, Gujarat had already established several different genres of literature. Firstly there was a rich collection of Jain literature in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Apabhramsha and old Gujarati.1) Such works were produced by Jain priests over many centuries and preserved in manuscripts, which were then stored in bhandars (storehouses) in 井坂理穂 Riho Isaka, Department of Area Studies, The University of Tokyo . Subject : Modern Indian History. Articles: "Language and Dominance: The Debates over the Gujarati Language in the Late Nineteenth Century", South Asia, 25-1 (April, 2002), pp. 1-19. "M . K. Gandhi and the Problem of Language in India" , Odysseus: Bulletin of the Department of Area Studies, The University of Tokyo, 5 (2000), pp. -

Rajendra Shukla - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Rajendra Shukla - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Rajendra Shukla(12 October 1942 -) Rajendra Shukla is a well known Gujarati poet. <b>Introduction to Kavi Shri Rajendra Shukla</b> Name: Rajendra Shukla Father: Anantray Shukla Mother: Vidyagauri Place of Birth: Bantwa, Dist. Junagadh, Gujarat. Date of Birth: 12 October 1942. Native place and the point of beginning and the source inspiration: Mt. Giranar, Junagadh city, Gujarat. Marriage: in 1974 with Nayana Jani, M.A. with entire English, First in Gujarat University, winner of F. C. Dawar Gold Medal (daughter of well-known scholar and folklorist Prof. Kanubhai Jani). Birth of son – Dhaivat – in 1975. Birth of son – Jajvalya – in 1977. <b>Education</b> Primary: Mainly at Bantwa, up to 1954. (at Jamnagar and Bhavnagar for short intervals in between) Secondary and Higher-secondary: Majevadi (dist. Junagadh) up to 1956. Junagadh – Bahadurkhanji High School up to 1957. Ahmedabad – H. B Kapadia High School (SSC) 1960 College education: Junagadh – Bahauddin College (Inter Arts) up to 1963. Ahmedabad – L. D. Arts College (B.A. Sanskrit-Prakrit)up to 1965 Ahmedabad – School of Languages, Gujarat University (M.A. Sanskrit-Prakrit, special subject Indian Poetics) up to 1967. <b>Teaching</b> Chhota Udaipur – Shri Natavarshimhji Arts College, 1967-1969 (Graduate Level) Ahmedabad – Gujarat Vidyapith, 1969-1970 (Postgraduate Level) Patan (North Gujarat) – Kotawala Arts College, 1970-1971 (Graduate & Postgraduate Levels) Ahmedabad – Vivekanand Arts College 1972-1973, part time (Graduate Level) Dahod – Navjivan Arts College, 1972–1973, part time (Graduate & Postgraduate Levels) Dahod – Navjivan Arts College, 1973–1977, full time (Graduate & Postgraduate Levels) Dahod – R. -

72 Course 1. History of Gujarati Language and Script Credits

Structure of B. A. Honours Gujarati under CBCS Gujarati Total Credits: 140 Core Courses Credits: 72 Course 1. History of Gujarati Language and Script Credits: 5+1 Unit of the course 1. Indo Aryan Languages and Gujarati 2. History of Gujarati Script. 3. Sources of Gujarati Language History 4. Phonological, Morphological, and syntactic changes 5. Semantic changes Preamble: This course aims at introducing the history of Gujarati language beginning from the origin of the Gujarati script. The latter texts of grammatical treatises, epics, commentaries etc., stand as the resource for the study of evolution of Gujarati during the medieval period. It discusses phonological, morphological, semantic, and syntactic changes taken place in the language. This course also explains the place of Gujarati in the indo Aryan languages, various dialects of Gujarati and the impact of Sanskrit and other languages in Gujarati. Prescribed Text: Kothari Jayant, Dhvani Parichay Ane Gujarati Bhashanu Swaroop,Ahmedabad,Gurjar Prakashan,2009 Bhayani, Harivallabh Vyutpattivichar. University Granth Nirman Board, Ahmedabad. 1975. Bhayani, Harivallabh. Gujarati Bhasha-nu Aitihasik Vyakran. Parshva Prakashan, Ahmedabad. 1996. Parikh, Pravinchandra C., Gujarat-maN Brahmi-thi Nagari sudhi-no Lipivikas: 1500 sudhi. Ahmedabad: Gujarat University. 1974. Reading list : Vyas K.B. Bhashavignan, Ahmedabad, University Book Production Board, 1985 Course 2. Language Varieties: Gujarati Credits: 5+1 Unit of the course 1. Indo Aryan Languages and Gujarati 3. Sources of Gujarati Language History 5. Semantic changes 6. Dialects of Gujarati Preamble: The course aims at creating an awareness of varieties in linguistic usage and their successful application in creative literature. It looks at various aspects of high literary language and rules of grammar in Gujarati alongside the common conversational/colloquial language. -

Department of Gujarati M.A. Sem-I (Gujarati) 2019-2020 CC-101 (A

Department of Gujarati M.A. Sem-I (Gujarati) 2019-2020 CC-101 (A Study of the Modern and Middle Age Texts) After completing this course the students are able: • To study ‘Amruta’ , ‘Prem Pachisy’ by Vishvanath Jani and Raghuvir Chaudhary. • To know about the unique literary work of India and the world. • To study of Modern Literature and Middle Age of Gujarati Literature. • To know the sensitivity in the work. CC-102 (Study of the forms of Literature: Drama)-(Angulimal –ed. Satish Vyas) After completing this course the students are able: • To understand the growth and development of Drama. • To understand the characteristics of Gujarati literature. • To understand the contemporary dramatists. CC-103 (Literature and Modernity) (Adhunik Varta Shrusti –(Strories) ed. Mohan Parmar) After completing this course the students are able: • To understand the modernity with reference of Gujarati Literature and western literature. • To understand various characteristics of modernity. • To understand the various ‘isms’ of Gujarati Literature. CC-104 (Folklore and Folk Literature: An Introduction) After completing this course the students are able: • To study the characteristics of Folk Literature. • To define Folk Literature and its inspiring factors. • To study folk tales and folk song like lok katha and Katha Geet. IDC -105 (Literature and Cinema) After completing this course the students are able: • To know the comprehensive traits of the literature. • To know the comprehensive traits of the cinema. • To understand the inter relation of Literature and Cinema. • To cultivate comparative approach through the medium of ‘Abhu Makrani’, ‘Mirch Masala’ and ‘Kanku’ as films. CC-201 [Study of the Authors of (Middle Age)] [Vansaladi- Dayaram. -

The Gujarati Lyrics of Kavi Dayarambhal

The Gujarati Lyrics of Kavi Dayarambhal Rachel Madeline Jackson Dwyer School of Oriental and African Studies Thesis presented to the University of London for the degree PhD July 1995 /f h. \ ProQuest Number: 10673087 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673087 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT Kavi Dayarambhal or Dayaram (1777-1852), considered to be one of the three greatest poets of Gujarati, brought to an end not only the age of the great bhakta- poets, but also the age of Gujarati medieval literature. After Dayaram, a new age of Gujarati literature and language began, influenced by Western education and thinking. The three chapters of Part I of the thesis look at the ways of approaching North Indian devotional literature which have informed all subsequent readings of Dayaram in the hundred and fifty years since his death. Chapter 1 is concerned with the treatment by Indologists of the Krsnaite literature in Braj Bhasa, which forms a significant part of Dayaram's literary antecedents. -

Contemporary Gujarati Poetry: for Whom Are They Writing?

Contemporary Gujarati Poetry: For Whom Are They Writing? Mukesh Modi, D. M. Patel Arts and S. S. Patel Commerce College Abstract: The writer here describes the various ages and traditions of Gujarati Poetry, looks into the present condition and questions the practice of writing poetry for the pundits’ sake. Middle Age Gujarati Poetry Gujarati poetry has basically evolved from Bhakti Literature of the 15th and 16th centuries. Oral tradition of Gujarati folklore dates back to the 12th century. So many seekers/devotees contributed immensely to the development of Gujarati poetry. Gujarati literature is divided broadly into two periods. The period from 12th century to the early 19th century is known as Middle Age, and the second period from 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century is known as Modern age. Looking at the Middle Age Gujarati literature, we find that the period was, as is the case with other Indian literature, dominated by poetry. In Gujarati, we have Narsinh Mehta Mirabai, Akho, Premanand, Shamal, Dayaram, Bhalan, Nakar, Bhim, Raje, Pritam, Dhiro, Bhojo and many others. With few exceptions, most of these poets liked to be known as devotees more and poets less. As Dr. Ramesh Trivedi mentions: “There was neither a consciousness of being poets nor attachment to being poets.” The central theme of Middle Age Gujarati Literature Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities Summer Issue, Volume I, Number 1, 2009 URL of the journal: www.rupkatha.com/issue0109.php URL of the article: www.rupkatha.com/0109contemporarygujaratipoetry.pdf © www.rupkatha.com Rupkatha Journal, Issue 1 2009 was religion. -

Gohilwad and Wessex: a Comparative Study of Regionalism in the Folk Fictions of Nanabhai Jebaliya and Thomas Hardy*

[VOLUME 3 I ISSUE 4 I OCT. – DEC. 2016] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Gohilwad and Wessex: A Comparative Study of Regionalism in the * Folk Fictions of Nanabhai Jebaliya and Thomas Hardy Dr. Dilip Bhatt Associate Professor & Ph. D. Supervisor, Department of English, V. D. Kanakia Arts and M. R. Sanghavi Commerce College, Savarkundla, Gujarat, India Received August 25, 2016 Accepted Sept 29, 2016 ABSTRACT Nanabhai is one of the least commented-upon and yet one of the most read fictioneers of contemporary Gujarati literature. The reticence and indifference of the so-called Gujarati literary academicians and critics can be conjectured from the creative output versus meagre critical reception of Nanabhai’s writings by Gujarati critics of today. For one or the other reasons, today’s Gujarati literature is only written and appreciated by a certain class of people. It seems that the Gujarati critic and criticism has gone astray by not paying attention to writers like Nanabhai. Gujarati critics look down upon those fictioneers who contribute in the newspapers and periodicals. Some of these call these writings cheap journalese. Moreover, the other reason of Nanabhai’s not among critics’ circles is that he is not a “college teacher” (since most of the critics are so and so are the “famous” creative writers!). Had Shakespeare born in Gujarat he would have never become famous, as he was only fourth-standard-primary-school-pass writer! Nanabhai has authored more than thirty books that are published by such highly acclaimed publishers as R.