The Emergence of Tragedy in Gujarati Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(73) History & Political Science

MT Seat No. 2018 .... .... 1100 MT - SOCIAL SCIENCE (73) History & Political Science - Semi Prelim I - PAPER VI (E) Time : 2 hrs. 30 min MODEL ANSWER PAPER Max. Marks : 60 A.1. (A) Choose the correct option and rewrite the complete answers : (i) Vishnubhat Godase wrote down the accounts of his journey from 1 Maharashtra to Ayodhya and back to Maharashtra. (ii) Harishchandra Sakharam Bhavadekar was also known as Savedada. 1 (iii) Louvre Museum has in its collection the much acclaimed painting of 1 Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci. (iv) Indian Hockey team won a gold medal in 1936 at Berlin Olympics 1 under the captaincy of Major Dhyanchand. A.1. (B) Find the incorrect pair in every set and write the correct one. (i) Atyapatya - International running race 1 Atyapatya is Indian outdoor game. (ii) Ekach Pyala - Annasaheb Kirloskar 1 Ekach Pyala is written by Ram Ganesh Gadkari. (iii) Bharatiya Prachin Eitihasik Kosh - Mahadev Shastri Joshi 1 Bharatiya Prachin Eitihasik Kosh - Raghunath Bhaskar Godbole (iv) Gopal Neelkanth Dandekar - Maza Pravas 1 Gopal Neelkanth Dandekar - Hiking tours A.2. (A) Complete the following concept maps. (Any Two) (i) 2 Pune Vadodara Kolhapur Shri Shiv Chhatrapati Kreeda Sankul Vyayam Kashbag Shala Talim Training centres for wrestling Swarnim Kreeda Gujarat Vidyapeeth Sports Hanuman Vyayam Prasarak Mandal Gandhinagar Patiyala Amaravati 2/MT PAPER - VI (ii) 2 (4) Name of the Place Period Contributor/ Artefacts Museum Hanagers (1) The Louvre Paris 18th C Members of the Royal MonaLisa, Museum family and antiquities 3 lakh and eighty brought by Napolean thousand artefacts Bonaparte (2) British London 18th C Sir Hans Sloan and 71 thousand Museum British people from objects British Colonies Total 80 lakh objects (3) National USA 1846CE Smithsonian 12 crore Museum Institution (120 millions) of Natural History (iii) Cultural Tourism 2 Visiting Educational Institutions Get a glimpse of local culture history and traditions Visiting historical monuments at a place Appreciate achievements of local people Participating in local festivals of dance A.2. -

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Kirtan Leelaarth Amrutdhaara

KIRTAN LEELAARTH AMRUTDHAARA INSPIRERS Param Pujya Dharma Dhurandhar 1008 Acharya Shree Koshalendraprasadji Maharaj Ahmedabad Diocese Aksharnivasi Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Hariswaroopdasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) Param Pujya Mahant Sadguru Purani Swami Dharmanandandasji Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj (Kutch) PUBLISHER Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple (Kenton-Harrow) (Affiliated to Shree Swaminarayan Mandir Bhuj – Kutch) PUBLISHED 4th May 2008 (Chaitra Vad 14, Samvat 2064) Produced by: Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton Harrow All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. © Copyright 2008 Artwork designed by: SKSS Temple I.T. Centre © Copyright 2008 Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple - Kenton, Harrow Shree Kutch Satsang Swaminarayan Temple Westfield Lane, Kenton, Harrow Middlesex, HA3 9EA, UK Tel: 020 8909 9899 Fax: 020 8909 9897 www.sksst.org [email protected] Registered Charity Number: 271034 i ii Forword Jay Shree Swaminarayan, The Swaminarayan Sampraday (faith) is supported by its four pillars; Mandir (Temple), Shastra (Holy Books), Acharya (Guru) and Santos (Holy Saints & Devotees). The growth, strength and inter- supportiveness of these four pillars are key to spreading of the Swaminarayan Faith. Lord Shree Swaminarayan has acknowledged these pillars and laid down the key responsibilities for each of the pillars. He instructed his Nand-Santos to write Shastras which helped the devotees to perform devotion (Bhakti), acquire true knowledge (Gnan), practice righteous living (Dharma) and develop non- attachment to every thing material except Supreme God, Lord Shree Swaminarayan (Vairagya). There are nine types of bhakti, of which, Lord Shree Swaminarayan has singled out Kirtan Bhakti as one of the most important and fundamental in our devotion to God. -

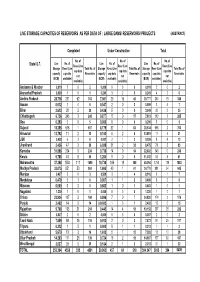

Live Storage Capacities of Reservoirs As Per Data of : Large Dams/ Reservoirs/ Projects (Abstract)

LIVE STORAGE CAPACITIES OF RESERVOIRS AS PER DATA OF : LARGE DAMS/ RESERVOIRS/ PROJECTS (ABSTRACT) Completed Under Construction Total No. of No. of No. of Live No. of Live No. of Live No. of State/ U.T. Resv (Live Resv (Live Resv (Live Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of Storage Resv (Live Total No. of cap data cap data cap data capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs capacity cap data Reservoirs not not not (BCM) available) (BCM) available) (BCM) available) available) available) available) Andaman & Nicobar 0.019 20 2 0.000 00 0 0.019 20 2 Arunachal Pradesh 0.000 10 1 0.241 32 5 0.241 42 6 Andhra Pradesh 28.716 251 62 313 7.061 29 16 45 35.777 280 78 358 Assam 0.012 14 5 0.547 20 2 0.559 34 7 Bihar 2.613 28 2 30 0.436 50 5 3.049 33 2 35 Chhattisgarh 6.736 245 3 248 0.877 17 0 17 7.613 262 3 265 Goa 0.290 50 5 0.000 00 0 0.290 50 5 Gujarat 18.355 616 1 617 8.179 82 1 83 26.534 698 2 700 Himachal 13.792 11 2 13 0.100 62 8 13.891 17 4 21 J&K 0.028 63 9 0.001 21 3 0.029 84 12 Jharkhand 2.436 47 3 50 6.039 31 2 33 8.475 78 5 83 Karnatka 31.896 234 0 234 0.736 14 0 14 32.632 248 0 248 Kerala 9.768 48 8 56 1.264 50 5 11.032 53 8 61 Maharashtra 37.358 1584 111 1695 10.736 169 19 188 48.094 1753 130 1883 Madhya Pradesh 33.075 851 53 904 1.695 40 1 41 34.770 891 54 945 Manipur 0.407 30 3 8.509 31 4 8.916 61 7 Meghalaya 0.479 51 6 0.007 11 2 0.486 62 8 Mizoram 0.000 00 0 0.663 10 1 0.663 10 1 Nagaland 1.220 10 1 0.000 00 0 1.220 10 1 Orissa 23.934 167 2 169 0.896 70 7 24.830 174 2 176 Punjab 2.402 14 -

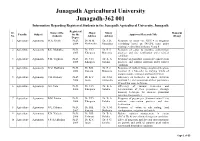

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

Folk Songs CLASS-II

Folk Songs CLASS-II 6 Notes FOLK SONGS A folk song is a song that is traditionally sung by the common people of a region and forms part of their culture. Indian folk music is diverse because of India's vast cultural diversity. It has many forms. The term folk music was originated in the 19th century, but is often applied to music older than that. The glimpse of rural world can be seen in the folk music of the villages. They are not only the medium of entertainment among the rural masses but also a reflection of the rural society. In this lesson we shall learn about the characteristics of folk songs and music and also about the various folk songs of India. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to: • define folk songs; • list the characteristics of folk songs and folk music; • list some famous forms of folk song of our country; and • describe the importance of folk song in our culture. OBE-Bharatiya Jnana Parampara 65 Folk Songs CLASS-II 6.1 MEANING OF FOLK SONGS AND MUSIC Music has always been an important aspect in the lives of Indian Notes people. India's rich cultural diversity has greatly contributed to various forms of folk music. Almost every region in India has its own folk music, which reflects local cultures and way of life. Folk songs are important to music because they give a short history of the people involved in the music. Folk songs often pass important information from generation to generation as well. -

Indian Cultural Dance Logos Free Download Indian Cultural Dance Logos Non Watermarked Dance

indian cultural dance logos free download indian cultural dance logos non watermarked Dance. Information on North Central Zonal Cultural Centre (NCZCC) under the Ministry of Culture is given. Users can get details of various art forms of various states such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana, Uttaranchal and Delhi. Get detailed information about the objectives, schemes, events of the centre. Links of other zonal cultural centers are also available. Website of Eastern Zonal Cultural Centre. The Eastern Zonal Cultural Center (EZCC) is one of the seven such Zonal Cultural Centers set up by the Ministry of Culture with a vision to integrate the states and union territories culturally. Users can get information about the objectives, infrastructure, events, revival projects, etc. Details about the member states and their activities to enhance the cultural integrity are also available. Website of Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. The Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts (IGNCA) under the Ministry of Culture is functioning as a centre for research, academic pursuit and dissemination in the field of the arts. Information about IGNCA, its organizational setup, functions, functional units, regional centres, etc. is given. Details related to archeological sites, exhibitions, manuscripts catalogue, seminars, lectures. Website of Jaipur Kathak Kendra. Jaipur Kathak Kendra is a premier Institution working for Training, Promotion & Research of North Indian Classical Dance Kathak. It was established in the year 1978 by the Government of Rajasthan and formally started working from 19th May 1979. Website of North East Zone Cultural Centre. North East Zone Cultural Centre (NEZCC) under Ministry of Culture aims to preserve, innovate and promote the projection and dissemination of arts of the Zone under the broad discipline of Sangeet Natak, Lalit Kala and Sahitya. -

Current Affairs November - 2018

MPSC integrated batchES 2018-19 CURRENT AFFAIRS NOVEMBER - 2018 COMPILED BY CHETAN PATIL CURRENT AFFAIRS NOVEMBER – 2018 MPSC INTEGRATED BATCHES 2018-19 INTERNATIONAL, INDIA AND MAHARASHTRA J&K all set for President’s rule: dissolves state assembly • Context: If the state assembly is not dissolved in two months, Jammu and Kashmir may come under President’s rule in January. What’s the issue? • Since J&K has a separate Constitution, Governor’s rule is imposed under Section 92 for six months after an approval by the President. • In case the Assembly is not dissolved within six months, President’s rule under Article 356 is extended to the State. Governor’s rule expires in the State on January 19. Governor’s rule in J&K: • The imposition of governor’s rule in J&K is slightly different than that in otherstates. In other states, the president’s rule is imposed under the Article 356 of Constitution of India. • In J&K, governor’s rule is mentioned under Article 370 section 92 – ‘ Provisions in case of failure of constitutional machinery in the State.’ Article 370 section 92: Provisions in case of failure of constitutional machinery in the State: • If at any time, the Governor is satisfied that a situation has arisen in which the Government of the State cannot be carried on in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution, the Governor may by Proclamation: • Assume to himself all or any of the functions of the Government of the State and all or any of the powers vested in or exercisable by anybody or authority in the State. -

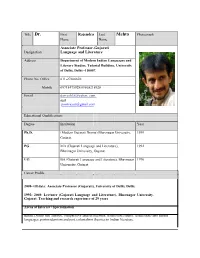

Dr Rajendra Mehta.Pdf

Title Dr. First Rajendra Last Mehta Photograph Name Name Associate Professor-Gujarati Designation Language and Literature Address Department of Modern Indian Languages and Literary Studies, Tutorial Building, University of Delhi, Delhi -110007. Phone No Office 011-27666626 Mobile 09718475928/09868218928 Email darvesh18@yahoo. com and [email protected] Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. (Modern Gujarati Drama) Bhavnagar University, 1999 Gujarat. PG MA (Gujarati Language and Literature), 1992 Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. UG BA (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar 1990 University, Gujarat. Career Profile 2008- till date: Associate Professor (Gujarati), University of Delhi, Delhi. 1992- 2008: Lecturer (Gujarati Language and Literature), Bhavnagar University, Gujarat. Teaching and research experience of 29 years Areas of Interest / Specialization Indian Drama and Theatre, comparative Indian literature, translation studies, translations into Indian languages, postmodernism and post colonialism theories in Indian literature. Subjects Taught 1- Gujarati language courses (certificate, diploma, advanced diploma) 2-M.A (Comparative Indian Literature) Theory of literary influence, Tragedy in Indian literature, Ascetics and poetics 3-M.Phil (Comparative Indian Literature): Gandhi in Indian literature. Introduction to an Indian language- Gujarati Research Guidance M.Phil. student -12 Ph.D. student - 05 Details of the Training Programmes attended: Name of the Programme From Date To Date Duration Organizing Institution -

Bhavai Introduction and History

Paper: 2 Relationship Of Dance And Theatre, Study Of Rupaka And Uparupaka, Traditional Theatres Of India Module 11 Bhavai Introduction And History Bhavai is an extraordinary and unparalleled example of performing arts in Gujarat. It is rich with history, acting, dramatic inspiration and pleasure. There is free flow of the power of imagination. Sharp writing that focuses on important lessons for life revolves around a pithy story. New ideals of youth are chiseled out. Bhavai is an inspiration and holds a mirror to youth. Therefore there is a rationale behind the study of Bhavai. The following is a sketch of the proposed programme: 1) Arrive at fundamental resolutions to discuss how Bhavai can fit into the modern era. 2) Explore the resolutions necessary to accustom to the contemporary era, and where to derive advice and consultations for the same? 3) Brainstorming over means to encourage Bhavai performances. Thinking about solutions like organising competitions, monoacts, and writing on new situations and encouraging other actions on similar thought. 4) To popularise the best Bhavai acts ever staged 5) To think about the possibilities and means by which Bhavai performers can contribute to the Indian governments initiatives, 1 just like people from other professions/disciplines are contributing in their own manner. 6) To organise all Bhavai groups on a common platform 7) To make efforts to address the existential issues of all Bhavai groups 8) To provide systematic training to rising stars of Bhavai so that the art form can exist in the contemporary times. Also for the development of the said artists, make efforts to set up a respective social role so that Bhavai performers as well as the Bhavai genre can prosper and the grand legacy of Bhavai folk art is sustained. -

The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture

www.ijemr.net ISSN (ONLINE): 2250-0758, ISSN (PRINT): 2394-6962 Volume-7, Issue-2, March-April 2017 International Journal of Engineering and Management Research Page Number: 550-559 The Role of Indian Dances on Indian Culture Lavanya Rayapureddy1, Ramesh Rayapureddy2 1MBA, I year, Mallareddy Engineering College for WomenMaisammaguda, Dhulapally, Secunderabad, INDIA 2Civil Contractor, Shapoor Nagar, Hyderabad, INDIA ABSTRACT singers in arias. The dancer's gestures mirror the attitudes of Dances in traditional Indian culture permeated all life throughout the visible universe and the human soul. facets of life, but its outstanding function was to give symbolic expression to abstract religious ideas. The close relationship Keywords--Dance, Classical Dance, Indian Culture, between dance and religion began very early in Hindu Wisdom of Vedas, etc. thought, and numerous references to dance include descriptions of its performance in both secular and religious contexts. This combination of religious and secular art is reflected in the field of temple sculpture, where the strictly I. OVERVIEW OF INDIAN CULTURE iconographic representation of deities often appears side-by- AND IMPACT OF DANCES ON INDIAN side with the depiction of secular themes. Dancing, as CULTURE understood in India, is not a mere spectacle or entertainment, but a representation, by means of gestures, of stories of gods and heroes—thus displaying a theme, not the dancer. According to Hindu Mythology, dance is believed Classical dance and theater constituted the exoteric to be a creation of Brahma. It is said that Lord Brahma worldwide counterpart of the esoteric wisdom of the Vedas. inspired the sage Bharat Muni to write the Natyashastra – a The tradition of dance uses the technique of Sanskrit treatise on performing arts. -

Swaminarayan Bliss March 2009

March 2009 Annual Subscription Rs. 60 HONOURING SHASTRIJI MAHARAJ February 2009 In 1949, Atladara, thousands of devotees ho- noured Brahmaswarup Shastriji Maharaj on his 85th birthday by celebrating his Suvarna Tula. The devotees devoutly weighed Shastriji Ma- haraj against sugar crystals and then weighed the sugar crystals against gold. To commemorate the 60th anniversary of this historic occasion, on 2 February 2009, the devotees of Atladara re-enacted it in the pres- ence of Pramukh Swami Maharaj. Weighing scales were set up under the same neem tree (above) where the original celebration took place. On one side a murti of Shastriji Maharaj was placed and on the other side sugar crystals. Devotees dressed in the traditions of that period joyfully hailed the glory of Shastriji Maharaj. Swamishri also participated in the celebration by placing sugar crystals on the scales. Then, on Sunday, 8 February 2009, the occasion was celebrated on the main assembly stage, and again Swamishri, the sadhus and devotees honoured Shastriji Maharaj (inset). March 2009, Vol. 32 No. 3 CONTENTS FIRST WORD 4 Bhagwan Swaminarayan The Vaishnava tradition in Hinduism Personal Magnetism Maharaj’s divine murti... believes that God manifests on earth in four 7 Sanatan Dharma ways: (1) through his avatars (vibhav) in Worshipping the Charanarvind of God times of spiritual darkness, (2) through his Ancient tradition of Sanatan Dharma... properly consecrated murti (archa) in 8 Bhagwan Swaminarayan mandirs, (3) within the hearts of all beings as The Sacred Charanarvind of Shriji Maharaj their inner controller (antaryamin) and (4) in Darshan to paramhansas and devotees... the form of a guru or bona fide sadhu.