New Estimates of the Mean Ethanol Content of Beer, Wine, and Spirits Sold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drink Choices

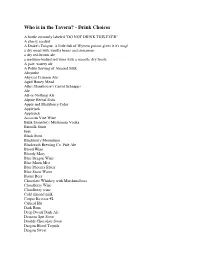

Who is in the Tavern? - Drink Choices A bottle curiously labeled "DO NOT DRINK THIS EVER" A cherry cordial A Drake's Tongue. A little dab of Wyvern poison gives it it's zing! a dry mead with vanilla beans and cinnamon a dry red-brown ale a medium-bodied red wine with a smooth, dry finish A pale, watery ale A Polite Serving of Almond Milk Absynthe Abyssal Crimson Ale Aged Honey Mead Albis Shinehouse's Carrot Schnapps Ale All-or-Nothing Ale Alpine Herbal Soda Apple and Blackberry Cider Applejack Applejack Assassin Vine Wine Balik Stonefist's Mushroom Vodka Batmilk Stout beer Black Stout Blackberry Moonshine Blackwish Brewing Co. Pale Ale Blood Wine Bloody Mary Blue Dragon Wine Blue Moon Mist Blue Phoenix Elixir Blue Snow Water Butter Beer Chocolate Whiskey with Marshmallows Cloudberry Wine Cloudberry wine Cold almond milk Corpse Reviver #2 Critical Hit Dark Rum Deep Dwarf Dark Ale Demons Spit Stout Double Chocolate Stout Dragon Blood Tequila Dragon Sweat Dragon's Breath Ginger Beer Dragon's Breath Liquer Drambuie Dry red wine with sugared fruit slices. Dry white wine, aged in oak Dwarven Ale Dwarven Stout Elderblossom Wine Eleven Pear Cider from Imratheon Elorian Sprite Wine Elven Honey Mead Elven Pale Ale Elverquist (rare elven wine) Elvish Mint Tea Elvish Pale Ale Emerald Dream (absinthe) Fermented Owlbear Blood Firefly Ale -- For when you want to have a healthy glow about you. Firewine Five Foot's Frothingslosh Flametongue-Hellfire Pepper Porter fragrant mug of hot chamomile tea Ghost pepper pineapple juice Gimlet Ginger Scald Gnoll Booger -

A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 7-3-2018 A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 Lyndsay Danielle Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Lyndsay Danielle, "A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: the Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4497. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A Temperate and Wholesome Beverage: The Defense of the American Beer Industry, 1880-1920 by Lyndsay Danielle Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Catherine McNeur, Chair Katrine Barber Joseph Bohling Nathan McClintock Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Lyndsay Danielle Smith i Abstract For decades prior to National Prohibition, the “liquor question” received attention from various temperance, prohibition, and liquor interest groups. Between 1880 and 1920, these groups gained public interest in their own way. The liquor interests defended their industries against politicians, religious leaders, and social reformers, but ultimately failed. While current historical scholarship links the different liquor industries together, the beer industry constantly worked to distinguish itself from other alcoholic beverages. -

Beer and Malt Handbook: Beer Types (PDF)

1. BEER TYPES The world is full of different beers, divided into a vast array of different types. Many classifications and precise definitions of beers having been formulated over the years, ours are not the most rigid, since we seek simply to review some of the most important beer types. In addition, we present a few options for the malt used for each type-hints for brewers considering different choices of malt when planning a new beer. The following beer types are given a short introduction to our Viking Malt malts. TOP FERMENTED BEERS: • Ales • Stouts and Porters • Wheat beers BOTTOM FERMENTED BEERS: • Lager • Dark lager • Pilsner • Bocks • Märzen 4 BEER & MALT HANDBOOK. BACKGROUND Known as the ‘mother’ of all pale lagers, pilsner originated in Bohemia, in the city of Pilsen. Pilsner is said to have been the first golden, clear lager beer, and is well known for its very soft brewing water, which PILSNER contributes to its smooth taste. Nowadays, for example, over half of the beer drunk in Germany is pilsner. DESCRIPTION Pilsner was originally famous for its fine hop aroma and strong bitterness. Its golden color and moderate alcohol content, and its slightly lower final attenuation, give it a smooth malty taste. Nowadays, the range of pilsner beers has extended in such a way that the less hopped and lighter versions are now considered ordinary lagers. TYPICAL ANALYSIS OF PILSNER Original gravity 11-12 °Plato Alcohol content 4.5-5.2 % volume C olor6 -12 °EBC Bitterness 2 5-40 BU COMMON MALT BASIS Pale Pilsner Malt is used according to the required specifications. -

Development Laboratories for Alcoholic Beverages

Asahi Breweries, Ltd. Development Laboratories for Alcoholic Beverages Striving to create products that are sure to delight customers We are engaged in the development of new products across prod- uct lines including beer and related products (beer, happoshu [low-malt beer], new genre, etc.), ready-to-drink (RTD) alcoholic beverages (chuhai, cocktails, etc.), shochu, wine, and non-alcohol beverages (beer-taste and cocktail-taste beverages, etc.). From small-scale production of prototypes to follow-up for mass pro- duction at breweries and distilleries, we are always striving to create products that are sure to delight customers. Development of brewed alcoholic Development of RTD alcoholic Development of distilled beverages beverages alcoholic beverages When developing beer, wine and other For the development of canned chuhai and In the development of distilled alcoholic li- brewed alcoholic beverages, we produce cocktails, referred to as RTD alcoholic bev- quors such as shochu and spirits, a variety small batches of prototypes in a small-scale erages, we study techniques for preparing of factors and conditions need to be deter- plant to determine the flavor profile for the and blending ingredients such as fruit juice mined, from ingredient selection and pro- new product. Through this process, various and other flavoring agents to propose new cessing, yeast selection, as well as condi- factors and conditions will be determined flavors and meet the ever diversifying tions for wort preparation, fermentation, including the type and quantity of ingredi- tastes of consumers. We also explore and distillation, filtration, and maturation. New ents (malt, hop, grapes, etc.) to use, selec- evaluate new ingredients to create innova- product development entails the optimiza- tion of fermenting yeast, fermentation tem- tive flavors. -

Analytical Records Three Qualities

1265 130 is the conclusion of a story about a man who sold matter, 4’7 ° 58 per cent. The total nitrogen amounted to 4’00 an idea with money in it for a glass of beer. The astute per cent. Primox is a highly concentrated preparation and buyer of the idea, which was that of a zinc collar-pad should be useful as an emergency food. We attach little to prevent horses getting sore necks, argued "that the importance on dietetic grounds to the addition of vegetables matter oozing from the sores on the horses’ necks would in this preserved state. corrode the zinc pad and produce sulphate of zinc- LAUREL CAMPHOR SOAP (MILNE). thus the disease would provide its own remedy." It may be (THE GALEN MANUFACTURING Co., LIMITED. WiMON-STBEET, said that this was only the idea of the buyer, but the authors NEW CROSS-ROAD, LONDON, S.E.) of the book let it pass without a word of comment. Some This soap proved to be well made, containing a minimum salts of zinc would undoubtedly be produced, but surely not of moisture and giving absolutely no indication of alkaline the sulphate. However, as a whole the book puts the argu- excess. It is soft and agreeable to the skin and possesses an of ments for temperance in a forcible manner, but we do attractive odour. The soap is said to contain the oil think that in a book specially intended for schools such the camphor laurel, tar phenols and cymene. It yields a is suitable for errors as we have indicated should have no place. -

TTB Ruling 2008-3

DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY TTB Ruling Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau TTB Ruling Number: 2008–3 July 7, 2008 Classification of Brewed Products as “Beer” Under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 and as “Malt Beverages” Under the Federal Alcohol Administration Act The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau issues this ruling to clarify that certain brewed products that are classified as “beer” under the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 do not meet the definition of a “malt beverage” under the Federal Alcohol Administration Act. TTB Ruling 2008–3 Background In recent months, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) has received inquiries from brewers regarding the labeling standards that apply to beers produced from substitutes for malted barley, such as rice or corn. We also have fielded questions from brewers and importers regarding the appropriate labeling of beers that are made without hops. This ruling explains the statutory criteria for classification of products as “beer” and “malt beverages” under the applicable laws and regulations. Laws and Regulations Federal Alcohol Administration Act Sections 105(e) and (f) of the Federal Alcohol Administration Act (FAA Act), 27 U.S.C. 205(e) and (f), vest broad authority in the Secretary of the Treasury to prescribe regulations with respect to the labeling and advertising of wine, distilled spirits, and malt beverages that are introduced into interstate or foreign commerce or imported into the United States. Section 105(e) also provides that no person may bottle, or remove from customs custody in bottles, distilled spirits, wine, or malt beverages unless he has obtained a certificate of label approval issued in accordance with regulations prescribed by the Secretary. -

Journ of Intell Prop 7

141 Journal of Intellectual Property. Companies and Intellectual Property Office Dominica VOL. 5 ROSEAU, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2014 NO. 7 Applications for Trademark Registration CHINA RESOURCES SNOW BREWERIES COMPANY LTD. of CHINA RESOURCES SNOW BREWERIES COMPANY LTD. of ROOM 306 CHINA RESOURCES BUILDING, NO. 8 JIANGUOMEN Room 306 CHINA RESOURCES BUILDING, NO. 8 JIANGUOMEN NORTH AVENUE, DONGCHENG DISTRICT, BEIJING, CHINA, NORTH AVENUE, DONGCHENG DISTRICT, BEIJING, CHINA, 100005 has applied through their agent, DUPIGNY, BRUNEY 100005 has applied through their agent, DUPIGNY, BRUNEY & ASSOCIATES of 20 HANOVER STREET, ROSEAU, COMMON- & ASSOCIATES of 20 HANOVER STREET, ROSEAU, COMMON- WEALTH OF DOMINICA, to the Companies and Intellectual WEALTH OF DOMINICA, to the Companies and Intellectual Property Office for the registration of one trade mark Property Office for the registration of one trade mark consisting of the following device, based on an application consisting of the following device, based on an application received on the 9th day of July, 2014 received on the 9th day of July, 2014 in Class 32 that is to say: Beer, Ginger Ale/Ginger Beer, in Class 32 that is to say: Beer, Ginger Ale/Ginger Beer, Malt Beer, Beer wort, Hops (Extracts of) for making Malt Beer, Beer wort, Hops (Extracts of) for making Beer, Malt wort. Beer, Malt wort. Any person may within two (2) months from the date Any person may within two (2) months from the date of the first publication of this advertisement in the Intellec- of the first publication of this advertisement in the Intellec- tual Property Journal, file a notice of opposition in Form 3 tual Property Journal, file a notice of opposition in Form 3 at the Companies and Intellectual Property Office, of the at the Companies and Intellectual Property Office, of the opposition to the registration of the said trademark. -

American Craft Beer and Food

AMERICAN CRAFT BEER AND FOOD: PERFECT COMPANIONS AMERICA’S HOT CRAFT BEER SCENE During the 1960s and 1970s, many young Americans traveled abroad, seeking new and exciting experiences. Among these were memo- rable encounters with classic European beers. When travel- ers returned, some sought to recreate those experiences by brewing, first at home, and then in small commercial breweries. By 1980, there were four or five of these new craft breweries. Presently, thou- sands of small, independent and traditional breweries are creating exciting, uniquely American interpretations of every imaginable style of beer. This abundance of flavorful beers led to economic growth. The U.S. craft beer category continues to grow rapidly. Beer lovers clearly appreciate the flavor, diversity and quality of the new American beer scene. These creative brewers have produced a range of delicious beers to suit nearly every kind of food. Here we present a brief introduction to the pleasures of American craft beer as a dining companion. Enjoy! 2 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages 4–5 The Principles of Beer & Food Matching Pages 6–7 Beer with Various Types of Food Pages 8–9 Beer & Food Matching Chart Page 10 Serving Up the Perfect Beer Experience Page 11 Cooking with Beer Back Cover About the Brewers Association WHAT IS CRAFT BEER? It is generally agreed to mean all-malt beer brewed with traditional methods and ingredients, inspired by classic styles. Brewed by small, independent breweries, craft beer offers a huge range of colors, flavors, strengths and sensations. Naturally, it makes a great companion to the wide world of foods. -

Baseline Study of the Liquor Industry Including the Impact of the National Liquor Act 59 May 2011 of 2003

Baseline study of the liquor industry Including the impact of the National Liquor Act 59 May 2011 of 2003 AUTHORS Sarah Truen Yash Ramkolowan Joanne Corrigall (UCT) Richard Matzopoulos (UCT) 4th Floor, South Office Tower, Hatfield Plaza, 1122 Burnett Street, Hatfield, Pretoria, 0083, South Africa PO Box 95838, Waterkloof, 0145, South Africa Tel +27 (0)12 362 0025 | Fax +27 (0)12 362 0210 | Email [email protected] | www.dnaeconomics.com DNA Economics is the registered business and trading name of Development Network Africa (Pty) Ltd Company Registration: 2001/023453/07│Directors: Elias Masilela, Matthew Stern Department of Trade and Industry Baseline study of the National Liquor Act 59 of 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ I 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 2 VALUE CHAIN ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Relevant economic concepts ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Inputs into alcoholic beverages ........................................................................................................................ 5 2.2.1 Agricultural products ......................................................................................................................................... -

Trouble Brewing

" " " " " Trouble"Brewing:"" Brewers’"Resistance"to"Prohibition"and"Anti: German"Sentiment" " " " " " Daniel'Aherne' " " " Honors"Thesis"Submitted"to"the" Department"of"History,"Georgetown"University" Advisor:"Professor"Joseph"McCartin" Honors"Program"Chair:"Professor"Amy"Leonard" " " " 9"May"2016" 1" " Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 I."Introduction 5 Why Beer 5 Prohibition in Europe 6 Early Temperance and State Prohibition in United States 8 Historical Narratives of Temperance and Prohibition 18 Brewers’ Muted Response 22 II. When Beer is Bier It’s Hard to Bear: How America’s Beer Became German 27 Lager Beer’s Inescapable German Identity 32 III."Band of Brewers: Industrial Collective Action in Brewers’ Associations 40 United States Brewers’ Association and the Origins of Brewer Cooperation and Lobbying 43 The USBA, Arthur Brisbane, and the Washington Times 48 Brotherly Brewing: A Brief History of Brewing in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania 56 “Facts Versus Fallacies”: Brewers Set the Record Straight 63 Popular Response After the War 68 Brewers and Labor: A Marriage of Necessity 72 Conclusions on Competition and Collective Action 78 IV. A King Without a Throne: Anheuser-Busch’s Struggle to Stave off Prohibition 80 How French St. Louis Became a Land of Germans and Beer 83 The Rise of Anheuser-Busch 89 Early Brand Advertising 94 Anheuser-Busch Changes Its Tune 97 V. From Drought to Draught: The Return of Beer and the End of the Great American Hangover 107 Beer and Volstead 110 Brewers’ During Prohibition 113 Conclusion 118 Epilogue 123 -

Journal-2019-06

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY REGISTRY OF SAMOA (IPROS) JOURNAL 2019/06 Publication Date – 4 December 2019 GENERAL INFORMATION The Public is hereby notified that the following persons have applied for the Registration of the Trade Marks as set out in Section 50 of the Intellectual Property Act 2011. Any person who wishes to oppose the registration of any of the under-mentioned Trade Marks, must give notice to the Registrar of Trade Marks, c/- Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Labour, Apia, Samoa within three (3) months from the date of this publication. The notice must be in writing and must include a statement of the grounds of opposition. Each notice of opposition must be accompanied by a filing fee of WST$300. Any person who has any doubts as to whether he/she may be affected by the registration of the Trade Mark in Samoa should consult his/her Solicitor immediately. For any enquiries regarding Trade Marks, please contact the Registry of Intellectual Property at the following telephone number (+685) 20441 or email [email protected] Faafetai, Registrar of Intellectual Property Accepted Trade Marks – Direct Filing (NEWSPAPER VERSION) Application No. : WS/T/7350 Representation of Mark Filing Date : 12 September, 2018 Priority Date : N/A Proprietor/Address : NEST CONSTRUCTION COMPANY LTD Vaitele Uta, Samoa Class(es) 37 Application No. : WS/T/7361 Representation of Mark Filing Date : 24 September, 2018 Priority Date : N/A Proprietor/Address : NIKE INNOVATE C.V. One Bowerman Drive, Beaverton, Oregon 97005--6453, United States of America Class(es) 18 and 25 Application No. : WS/T/7464 Representation of Mark Filing Date : 29 July, 2019 Priority Date : 04/03/2019 Proprietor/Address : REIGN BEVERAGE COMPANY LLC 1547 N. -

Grand Ridge Brewery Mirboo North, Victoria

Grand Ridge Brewery Mirboo North, Victoria Brewery Profile, Product Range and Tasting Notes Grand Ridge Brewery – Our Story The Grand Ridge Brewery is situated in a small country town in the Gippsland region of Victoria, called Mirboo North. The site was chosen for its exceptional water quality for beer making, given its position on the top of the mountains in the Strzelecki ranges. After extensive product testing to achieve the highest standards in pure beer, Grand Ridge, one of the pioneers in the Australian Craft Beer Industry commenced brewing in June 1989. Grand Ridge Brewery is 100% Independently Australian family owned company. At Grand Ridge the quality of the beer and cider is never compromised. All the beers are produced to exceptionally high standards of flavour and purity, with no added chemicals, sugars or preservatives. Our Twisted Sister Craft Cider is made with 100% Australian Fruit and made without the use of concentrates or added sugars and is Gluten free and Vegan. The quality of the Grand Ridge beers and ciders continue to be recognised with over 200 Australian and International beer awards and most recently Grand Ridge won awards at the 2015 & 2016 Australian International Beer Awards, 2015 & 2016 Sydney Royal Beer and Cider Show and 2015 & 2016 Cider Australia National Awards. In January 2017, Grand Ridge secured a long term beer and cider partnership with Melbourne Arts Centre, Hamer Hall and Sidney Myer Music Bowl. This is a highly strategic partnership with one of Australia’s most iconic On Premise and Stadia groups which will drive exposure of our brands to approximately 3 million visitors each year.