"Merciless Indian Savages" and the Declaration of Independence: Native Americans Translate the Ecunnaunuxulgee Document John R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wanamaker-Grand-Court.Pdf

5. Boundary Description The Grand Court of the former John Wanamaker Store at 1301-25 Chestnut Street is a seven- story open interior volume measuring approximately 122 feet long by 66 feet wide and 150 feet high. The clear-span area is enclosed by a ground-floor perimeter arcade and upper-floor colonnade walls rising the full height of the space. The boundaries of this nomination include the entire Grand Court volume from floor to ceiling; the inner, outer, and intrados surfaces of the ground-floor arcade; the inward and lateral-facing surfaces of the upper-floor columns and colonnade walls; the architectural elements that span between and in plane with these columns; and all components of the Wanamaker Organ visible from within the Court, including the organ console located in the middle bay of the east second-floor gallery. These boundaries exclude the outer faces of the upper-floor colonnade walls and those portions of the Wanamaker Organ that are not visible from within the Court. This defined Grand Court area satisfies the definition of a public interior eligible for historic designation as set forth in the Philadelphia Historic Preservation Ordinance and defined in the Philadelphia Zoning Code, §14-203 (252) as “an interior portion of a building or structure that is, or was designed to be, customarily open or accessible to the public, including by invitation,” and which retains “a substantial portion of the features reflecting design for public use.” The visible Wanamaker Organ components satisfy the definition of fixtures of a public interior space as set forth in the Philadelphia Historical Commission Rules and Regulations 2.10. -

John Wanamaker Collection 2188

John Wanamaker collection 2188 Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania ; March 2013 John Wanamaker collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 Series I. Personal records........................................................................................................................ 9 Series II. Store records.......................................................................................................................... 32 Series III. Miscellaneous -

Rodman Wanamaker (1863-1928)

Rodman Wanamaker (1863-1928) He belonged to the Wanamaker department store family. In his free time, he used his wealth and influence to support many causes, including documenting Native American populations through photographic expeditions. He also hosted the first meeting which would later become the PGA (Professional Golfers Association) and was a professional golfer himself. In fact, the winner of the PGA championship receives the Wanamaker Trophy. Primary Sources: John and Rodman Wanamaker group portrait with Native American men [electronic resource] Published 1913 Call Number: 10844 Group photograph of Native American men with John and Rodman Wanamaker. Rodman Wanamaker is pictured shaking hands with one man while John Wanamaker is clasping hands with another. Photo was taken in conjunction with the groundbreaking of the (unbuilt) National American Indian Memorial in New York City. John Wanamaker Collection Box 207 Record Number: 10844 Digital Library Link: http://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/idno/10844 John and Rodman Wanamaker group portrait with Native American men (10844) HEAD for the Future is an education initiative by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in partnership with Wells Fargo. Rodman Wanamaker group portrait with Native Americans [electronic resource] Published 1913 Call Number: 12687 Formal portrait of Rodman Wanamaker gathered in Wanamaker's department store office with Native American men, possibly in conjunction with the groundbreaking of the (unbuilt) National American Indian Memorial in New York City. Collection: John Wanamaker collection [2188] Box Number: 118 Folder Number: 7 Record Number: 12687 Digital Library Link: http://digitallibrary.hsp.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/idno/12687 Rodman Wanamaker (picture) Rodman Wanamaker in an office space, filled with plants and flowers. -

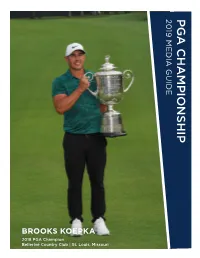

P G a C H a M P Io Nsh Ip

2019 MEDIA GUIDE MEDIA 2019 CHAMPIONSHIP PGA BROOKS KOEPKA 2018 PGA Champion Bellerive Country Club | St. Louis, Missouri 101ST PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 13-19, 2019 Bethpage Black Farmingdale, New York 102ND PGA CHAMPIONSHIP 103RD PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 2020 May 2021 Harding Park Golf Club The Ocean Course San Francisco, California Kiawah Island, South Carolina 104TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP 105TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 2022 May 2023 Trump National Golf Club Oak Hill Country Club Bedminster, New Jersey Pittsford, New York 106TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP 108TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 2024 May 2026 Valhalla Golf Club Aronimink Golf Club Louisville, Kentucky Newtown Square, Pennsylvania 109TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP 110TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 2027 May 2028 PGA Frisco The Olympic Club Frisco, Texas San Francisco, California 111TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP 113TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 2029 May 2031 Baltusrol Golf Club Congressional Country Club Springfield Township, New Jersey Bethesda, Maryland 116TH PGA CHAMPIONSHIP TBD PGA CHAMPIONSHIP May 2034 TBD PGA Frisco Southern Hills Country Club Frisco, Texas Tulsa, Oklahoma PGA MEDIA GUIDE 2019 | 1 101ST PGA CHAMPIONSHIP MAY 16-19, 2019 Bethpage Black, Long Island, New York Defending Champion: Brooks Koepka FACTS & FORMAT Purse and Honors The 2019 PGA Champion will have 9. Playing members of the last-named U.S. and European Ryder his name inscribed on the Wanamaker Trophy, which is Cup teams (2018) provided they remain within the top 100 on enshrined in the PGA Gallery at PGA Golf Club in Port St. the Official World Golf Rankings as of May 5, 2019. Lucie, Florida. The PGA Champion also receives a replica of 10. Winners of PGA TOUR co-sponsored or approved the Wanamaker Trophy. -

Rodman Wanamaker

Volume 68, Number 12 October 2018 John Bishop, editor Visit the website of the NYC AGO Chapter Don't miss events presented by your friends and colleagues. Visit the Concert Calendar of the NYC Chapter, and attend some concerts! Table of contents: Dean's Message Program News Quote of the Month Won't you be my neighbor? Joke of the Month From the Editor Dean's Message Fall is often seen as a natural time for new beginnings. That’s thanks in part to the dominance of the academic calendar that derives its timing from the postharvest season. For those who celebrate Judaism, September sees the celebration of Rosh Hashanah—the New Year— celebrated with liturgies that several of us will have been involved with as organists, singers, and congregants. Now is the perfect time to grow our Chapter. We have seen a steady increase in membership over the past few years which is most encouraging considering the downward trend that many chapters are experiencing. That’s due in part to some exciting programming, creative and engaging communication, clear and effective leadership, and an overall easier process of joining the Guild via the ONCARD online registration system. There are many reasons to join the guild, and I invite you to read this excellent article by David Vogels, published in The American Organist in 2015, for a detailed discussion of the benefits of AGO membership. Here are my top five reasons: 1. Stronger together! It’s true, more members mean more money to be spent on programs, which enables us to present bigger and better performances, conferences, masterclasses, and outreach events. -

Educational Requirements

2018 Turf Grad Program Turf Grad Program Bellerive offers a great opportunity for you to work and learn in an environment that consistently wants to improve. As a part of the Turf Grad program, you will have the opportunity to learn many skill sets such as fertility, pesticide management, moisture management, cultural practices, and receive career mentoring. Our goal here at Golf Operations is to help you lay a solid foundation on which to build a successful golf course management career. Surface Management You will be responsible for the management and championship preparation of all green, green complexes and fairway surface management. Each day you will have assigned area of greens and you will become familiar with the soil and apply necessary moisture, amendments, plugging and ensure a championship surface is displayed daily and through the 2018 PGA Championship. Moisture Management: At Bellerive, moisture management is held as the utmost priority due to the extreme environmental stresses that the Missouri weather puts on the bentgrass plant. With the use of moisture meters, you will learn to manage moisture to an exact percentage based on physical analysis, to optimize the balance between water and air in the soil profile. Career Mentoring: Building a strong agronomic foundation is important, but many interns miss building a strong professional background which can help land them the job they want. We believe education is of the utmost importance so we provide sessions on topics to separate our Turf Grads from the competition. At Bellerive, we hope to inspire, motivate, and coach you to the success for the future. -

Virgil Fox Memorial Concert

Virgil Fox Memorial Concert LORD & TAYLOR, PHILADELPHIA THE WANAMAKER ORGAN OCTOBER 7, 2001 VIRGIL FOX AT THE CONSOLE OF THE WANAMAKER ORGAN — Virgil Fox 1912-1980 VIRGIL FOX was born in Princeton, uate with the its highest honor—the Illinois, on May 3, 1912. He was a child Artist’s Diploma. In 1936, he returned to prodigy. At the age of ten, he was playing Baltimore to head the Peabody organ the organ for church services. At fourteen, department, and to serve as organist of he played his first organ recital before a Brown Memorial Church. cheering crowd of 2,500 people in In 1942, he enlisted in the Army Air Cincinnati. At seventeen, he was the unan- Force and performed 600 recitals in three imous winner of the Biennial Contest of years to raise money for the armed serv- the National Federation of Music Clubs in ices. After his discharge in 1946, Virgil Boston, the first organist ever chosen. Fox performed forty-four major works Before graduating in 1930 as saluta- from memory in a series of three concerts torian of his high school class, he studied given under the auspices of the Elizabeth for three years with Wilhelm Sprague Coolidge Foundation, before Middelschulte, Organist of the (now) sold-out audiences in the Library of Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In 1931, Congress. In the same year, he was he became a scholarship student at selected to be organist of New York City’s Peabody Conservatory in Baltimore, famed Riverside Church where he served America’s oldest music conservatory. In for nineteen years (with W. -

Who Killed John Wanamaker?

142028 – Journal of Management and Marketing Research Who killed John Wanamaker? Marvin G. Lovett The University of Texas at Brownsville Gerardo A. Miranda The University of Texas at Brownsville ABSTRACT Retailing has grown and continues to contribute significantly to the economy of the Unit- ed States, as well as to most other economies around the world. The study of retailing, as an ac- ademic field, continues to grow and evolve. The study of retail history and of its contributors provides beneficial insight. Retail commerce began to flourish in the United States well over a century ago. This study attempts to provide insight into the absence of an original and signifi- cant contributor to the field of retailing and marketing, John Wanamaker. In fact, John Wanamaker has been referred to as the “Father of Retailing.” He earned that title and reputation as an original and innovative successful retail entrepreneur and was responsible for numerous significant contributions to the field of retailing. However, current retail expertise, as voiced in current retail and marketing curricula and among marketing professors, is largely void of any recognition of John Wanamaker. This study initially reviews the significant contributions made by John Wanamaker to the field of retailing. Secondly, a survey to assess the current awareness of John Wanamaker among various marketing professors is administered and presented. Thirdly, a survey to assess the presence of John Wanamaker within current retail and marketing textbooks is administered and presented. Fourthly, an investigation into the reasons for the demise of the John Wanamaker brand and reputation is presented. Finally a discussion leads to recommenda- tions for current retail curricula. -

Oral History Interview with Robert Carlen, 1985 June 28-July 16

Oral history interview with Robert Carlen, 1985 June 28-July 16 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview CS: CATHARINE STOVER RC: ROBERT CARLEN AC: ALICE CARLEN CS: This is tape 1, side 1. Robert Carlen being interviewed by Catharine Stover for the Archives of American Art. The date is June 28, 1985. The interview is being conducted at the Carlen Galleries, 323 S. 16th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The time is 2 p.m. I understand that you're from Indianapolis. RC: Yeah, I was born out there. CS: What year? CS: 1906. CS: And when did you come to Philadelphia? CS: You know, I think it was a couple of years after that. We were having a lot of bad floods out there. You know, the river. My mother hadn't been well. She wanted to come east to get some medical advice and she was. she came here. She didn't like it out there; it was too lonely. It was all farmers. CS: Did you live on a farm? RC: We had a general store. We catered to the farmers. It was all Germans settling out there. So my mother decided she didn't want to come back. So we stayed here and my father tried to make a go here. See, it was very bad. You see, during the time there was an awful lot of business trouble. -

John Wanamaker Collection

Collection 2188 John Wanamaker Collection 1827-1987 327 boxes, 196 volumes, 365 lin. feet Contact: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street, Philadelphia, PA 19107 Phone: (215) 732-6200 FAX: (215) 732-2680 http://www.hsp.org Restrictions: None Related collections: The Yost Collection, 1861-1985 (no number) © 2008 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. All rights reserved. John Wanamaker collection Collection 2188 John Wanamaker Collection, 1827-1987 327 boxes, 196 volumes, 365 lin. feet Collection 2188 Abstract John Wanamaker (1838-1922) was a well-known merchant, entrepreneur, and lifelong resident of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was active in the city’s religious, political, and philanthropic areas, founded several Presbyterian churches and Sunday schools, and served as Postmaster General under President Benjamin Harrison from 1889 to 1893. He opened his first Philadelphia clothing store, Oak Hall, with partner Nathan Brown in 1861, and founded John Wanamaker and Co. several years later in 1869. In 1876, they opened “A New Kind of Store” known as the Grand Depot at 13th and Market Streets. This store later became the flagship store, which eventually branched out into central and southeastern Pennsylvania. Satellite stores were also established in New Jersey, Delaware, and New York City. Wanamaker was at the forefront in many areas in retailing including merchandising, employee relations and advertising. His sons Thomas B. Wanamaker and L. Rodman Wanamaker were also active in the business. Thomas ran John Wanamaker and Co. in Philadelphia and Rodman took over the New York store operations in 1906. This rich and extensive collection, which is arranged into five series and spans over one hundred and fifty years, details the history of Wanamaker’s store in Philadelphia and its influence as a major city retailer in during the 19 th and 20 th centuries. -

An American Heart of Darkness: the 1913 Expedition for American Indian Citizenship

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1993 An American Heart of Darkness: The 1913 Expedition for American Indian Citizenship Russel Lawrence Barsh Apamuek Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Barsh, Russel Lawrence, "An American Heart of Darkness: The 1913 Expedition for American Indian Citizenship" (1993). Great Plains Quarterly. 751. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/751 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AN AMERICAN HEART OF DARKNESS THE 1913 EXPEDITION FOR AMERICAN INDIAN CITIZENSHIP RUSSEL LAWRENCE BARSH In his pungent essay on Conrad's Heart of car Signet on a 20,OOO-mile journey that would Darkness, Chinua Achebe explores Europeans' take them to eighty-nine Indian reservations in literary use of African stereotypes to work out a little more than six months. Everywhere the their own psycho-social dilemmas.! The jour Signet stopped, Indian leaders were gathered to ney into Africa was in reality a journey inside listen to recorded messages from the president the confused souls of explorers and missionar of the United States and the commissioner of ies who sometimes found salvation there but Indian affairs, to hoist a large American flag to never saw, heard, or found the Africans. The their own drums, and to sign a vellum "Decla Africans they imagined were only a dark reflec ration of Allegiance of the North American tion of themselves. -

By Lloyd E. Klos the Wanamaker Grand Court Or- Gan! the Very

Tti~ by Lloyd E. Klos The Wanamaker Grand Court Or gan! The very sound of those words is in keeping with the prestigious rank which this instrument enjoys when one mentions the great pipe or gans of the world. Though it is not a theatre instrument per se, it does have some percussive stops, and the Wanamaker Store was a focal point for one of the sessions of the 1976 ATOS Convention in Philadelphia. The original organ was but a third the size of the present instrument. It was designed by George Ashdown Audsley and was built by the Los Angeles Art Organ Co. for the St. Louis Exposition in 1904. It required 11 box cars to move the 10,059 pipes, console, and other appurtenances. Not much is known about the or gan's early history. It was installed in the Festival Hall of the exposition, and was played by Alexander Guil rnont and nearly every great organist of the time. When the exposition closed in December 1904, the instru ment was dismantled and stored in a warehouse for six years. Enter Rod man Wanamaker. Organs and organ music have The Grand Court organ console . Notice the 11 ► expression pedals . There are 729 tablets and 168 pistons included in the 964 controls. It is situated in an alcove high above the main floor . IWa11,11naAPrPhmoJ 12 been a part of the John Wanamaker The console is situated in a niche high. tradition since 1876. The store's on the east side of the court. on the The percussion section is expres founder.