Outcomes of Using a Modified Seldinger Technique for Long Term Intravenous Therapy in Hospitalized Patients with Difficult Venous Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Venous Access with Accelerated Seldinger Technique Versus Modified Seldinger Technique

Central Venous Access with Accelerated Seldinger Technique versus Modified Seldinger Technique L A N E THAUT , D O , CAPT , M C , USAF SAN ANTONIO MILITARY MEDICAL CENTER CO- AUTHORS: WELLS WEYMOUTH, MD, DANIEL RESCHKE, MD, BRANDEN HUNSAKER,MD Disclosures Expired POWERWAND™ combination device kits were donated by Access Scientific for the express purpose to be used in this study; however, no other contributions were made. We approached Access Scientific to obtain the devices to conduct this study. No financial relationship with Access Scientific. Background Techniques Research and Outcomes Questions Background Air Force SAMMC San Antonio, TX Level 1 Trauma Center 85,000+ patients annually Central Access Common Procedure Approximately 8% of hospitalized patients Multiple indications Large volume fluid or blood product resuscitation Administration of central acting medications Multiple medications simultaneously Trans venous pacing Difficult peripheral access Quick Story What if there was a simpler/quicker way? Intra-osseous? Complications Slower Flow Rate Labs Traditional Central Line Multiple steps/parts Midlines Usually used for extended dwelling lines. Self contained, all in one device. Equivalent and sometimes superior flow rate. Question Will the use of combination devices (midline/POWERWAND™) and the associated accelerated technique reduce the time of CVC placement? VS What is Accelerated Seldinger Technique? Needle, guidewire, dilator, and sheath into one. The device needle is inserted into the target vein under ultrasound guidance and a flash is observed The internal guidewire is then advanced into the vein and snapped into the needle hub. Dilator collar is turned and the dilator and sheath are advanced The dilator hub is disengaged from the needle hub, and the guidewire, dilator, and needle are all removed as a single unit. -

Practice Parameter for the Use of Ultrasound to Guide Vascular Access Procedures

PRACTICE GUIDELINES AIUM Practice Parameter for the Use of Ultrasound to Guide Vascular Access Procedures I. Introduction he clinical aspects of this parameter were developed collaboratively among the AIUM and other organizations whose members use ultrasound for guidance in vascular T “ ” access procedures (see Acknowledgments ). Recommendations for practitioner requirements, the written request for the examination, procedure documentation, and quality control vary among the organizations and are addressed by each separately. This parameter has been developed by and for clinicians from diverse specialties and practitioner levels who perform vascular access. While vascular access may be performed using external landmarks, point-of-care ultrasound is now increasingly available.1 Appropriately used, ultrasound guidance for vascular access has been shown to improve success rates while reducing iatrogenic injury, the number of needle passes, and infection rates.2 Addition- ally, it may improve patient comfort and satisfaction. This parameter is intended to be evidence based when possi- ble and to include selected references of importance, but it is not meant to be a comprehensive or rigorous literature review, as this has been accomplished elsewhere.3 The intent of this document is to highlight appropriate evidence while also providing a practical, real-world expert consensus from clinicians with diverse back- grounds on the best use and techniques for incorporating ultra- sound into vascular access procedures with the ultimate goal of improving the care of our patients. II. Indications/Contraindications Ultrasound should be used to aid in central venous, peripheral venous, and arterial access procedures.4 When used appropriately by qualified personnel, there are no absolute contraindications to using ultrasound as a procedural adjunct for vascular guidance. -

Too Many Twos in One Patient: Two Central Venous Catheters, Two

& Experim l e ca n i t in a l l C Journal of Clinical and Experimental C f a o r d l i a o Chalwade, J Clin Exp cardiolog 2018, 9:9 n l o r g u y o Cardiology DOI: 10.4172/2155-9880.1000605 J ISSN: 2155-9880 Case Report Open Access Too Many Twos in One Patient: Two Central Venous Catheters, Two Routes, Two Hospitals, Two Lost Guidewires, Two Vascular Systems, One Patient Rahul Chalwade* Department of Cardiology, Felix Health Care, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India *Corresponding author: Rahul Chalwade, Department of Cardiology, Felix Health Care, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India, Phone: +919717053558; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: September 05, 2018; Accepted date: September 10, 2018; Published date: September 17, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Chalwade R. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Central venous catheter insertion by Seldinger's technique is a very common procedure nowadays. The technique though considered safe, is associated with potential dreaded complications. One such complication is intravascular loss of guidewire during insertion. We describe one unusual case of two chronically lost guidewires in venous and arterial system with successful retrieval by innovative interventional techniques. Keywords: Lost guidewire; Interventional cardiology; Interventionl AORTA-ARCH OF AORTA-LOOPING IN DESCENDING AORTA- radiology; Central venous catheter complications; Anaesthesiology; OPENING OF LT SCA (straight tip of guidewire). Snare We did routine blood evaluation, all were normal, venous and arterial Doppler and echo was done to rule out thrombus. -

First Simulator for Seldinger Technique and Angiography Training

This is a repository copy of ImaGiNe Seldinger: first simulator for Seldinger Technique and Angiography Training. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79950/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Luboz, V, Zhang, Y, Johnson, S et al. (20 more authors) (2013) ImaGiNe Seldinger: first simulator for Seldinger Technique and Angiography Training. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 111 (2). 419 - 434. ISSN 0169-2607 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.05.014 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ ImaGiNe Seldinger: first simulator for Seldinger technique and angiography training V. Luboz, Y. Zhang, S. Johnson, Y. Song, C. Kilkenny, C. Hunt, H. Woolnough, S. Guediri, J. Zhai, T. Odetoyinbo, P. Littler, A. -

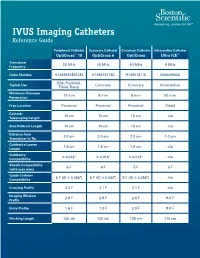

IVUS Imaging Catheters Reference Guide

IVUS Imaging Catheters Reference Guide Peripheral Catheter Coronary Catheter Coronary Catheter Intracardiac Catheter OptiCross™ 18 OptiCross 6 OptiCross Ultra ICE™ Transducer 30 MHz 40 MHz 40 MHz 9 MHz Frequency Order Number H7493932800180 H7495181160 H749518110 M00499000 SFA, Popliteal, Typical Use Coronary Coronary Intracardiac Tibial, Renal Maximum Diameter 12 mm 6 mm 6 mm 50 mm Penetration Prep Location Proximal Proximal Proximal Distal Catheter 15 cm 15 cm 15 cm n/a Telescoping Length Sled Pullback Length 10 cm 10 cm 10 cm n/a Distance from 2.0 cm 2.0 cm 2.0 cm 1.0 cm Transducer to Tip Guidewire Lumen 1.6 cm 1.6 cm 1.6 cm n/a Length Guidewire ≤ 0.018" ≤ 0.014" ≤ 0.014" n/a Compatibility Sheath Compatibility 6 F 6 F 5 F 9 F (with max wire) Guide Catheter 6 F (ID ≥ 0.068") 6 F (ID ≥ 0.064") 5 F (ID ≥ 0.058") n/a Compatibility Crossing Profile 3.5 F 3.1 F 3.1 F n/a Imaging Window 2.9 F 2.9 F 2.6 F 9.0 F Profile Entry Profile 1.6 F 1.3 F 2.0 F 9.0 F Working Length 135 cm 135 cm 135 cm 110 cm OPTICROSS™ 18 CATHETER AND MDU5 PLUS BAG OPTICROSS 6 40 MHZ CORONARY IMAGING CATHETER CAUTION Federal law (USA) restricts this device to sale by or on the order of a physician. Rx only. Prior to use, please see the CAUTION: Federal law (USA) restricts this device to sale by or on the order of a physician. -

Coding Billing

Coding&Billing Quarterly FEBRUARY 2015 EDITOR ALAN L. PLUMMER, MD ATS RUC Advisor Letter from the Editor Welcome to the January 2015 edition of the ATS Coding ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS: and Billing Quarterly. The New Year will bring a number of KATINA NICOLACAKIS, MD important changes to medicine for practitioners of pulmonary, Chair, ATS Clinical Practice Committee ATS Alternate RUC Advisor critical care and sleep medicine. Below are some issues that ATS STEPHEN P. HOFFMANN, MD members and their staff need to be aware of and prepared for: Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee ATS CPT Advisor ICD-10 Transition – Barring another last minute intervention MICHAEL NELSON, MD by Congress (which is possible but very unlikely), 2015 will Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee be the year of the ICD-10 transition. I hope providers and ATS Alternate CPT Advisor practices are well underway preparing for the transition. Over the past year, the STEVE G. PETERS, MD Member, ATS Clinical Practice Committee ATS Coding and Billing Quarterly has featured articles on the transition. The April 2015 edition will cover ICD-10 for pediatric pulmonary services. Lung Cancer Screening Coverage – Earlier this month, the Centers for Medicare In This Issue and Medicaid Services (CMS) released its final coverage policy for lung cancer Low Dose CT Lung Cancer screening. In this issue, Dr. Kovitz describes the final coverage policy, its impact Screening Coverage - Implications on Medicare and private coverage, as well as tips for coding services related to for the Practitioner, page 2 screening. 2015 Brings New Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation New ECMO codes – Also covered in this issue is the new and expanded family of (ECMO)/Extracorporeal Life codes for EMCO services. -

Open Seldinger-Guided Peripheral Femoro-Femoral Cannulation

Chen et al. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery (2021) 16:199 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-021-01584-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Open Seldinger-guided peripheral femoro- femoral cannulation technique for totally endoscopic cardiac surgery Yi Chen1,2, Liang-wan Chen1, Xiao-fu Dai1 and Xue-shan Huang1,2* Abstract Background: The cannulation technique used in totally endoscopic cardiac surgery has a significant impact on the overall prognosis of patients. However, there are no large cohort studies to discuss it. Here we report on our research of using open Seldinger-guided technique to establish femoro-femoral cardiopulmonary bypass during totally endoscopic cardiac surgery and evaluate its safety and efficacy. Methods: The institutional database from 2017 to 2020 was retrospectively reviewed to find cases in which totally endoscopic cardiac surgery was performed. We identified 214 consecutive patients who underwent totally endoscopic cardiac surgery with peripheral femoro-femoral cannulation. All patients underwent femoral artery cannulation. Of these, 201 were cannulated in the femoral vein and 13 were cannulated in the femoral vein combined with internal jugular cannulation. The technique involves surgically exposing the femoral vessel, setting up purse-string over the vessels and then inserting a guidewire into the femoral vessel without a vascular incision, followed by exchange of the guidewire with a cannula. Results: Surgery indications included mitral valve disease in 82.71% (177/214), atrial septal defect in 11.68% (25/214) and tricuspid regurgitation in the remaining 5.61% (12/214). Hospital survival was 98.60% (211/214). There were no cases of stroke and postoperative limb ischaemia. -

Emergency Management of the DKA Patient

COMMON EMERGENCY ROOM PROCEDURES Garret Pachtinger, VMD, DACVECC Associate, BluePearl PA Co-Founder, VETgirl ABDOMINOCENTESIS Abdominocentesis is a minimally invasive, inexpensive, diagnostic and potentially therapeutic procedure for patients with ascites. Evaluation of the fluid aids in diagnosis and helps guide treatment. Abdominal effusion is classified as a transudate, modified transudate, or exudate based on the cellularity and protein content of the fluid. Transudates (protein concentration < 25 g/l, nucleated cell count < 1000/l (1 x 109/l)), are commonly due to causes including hypoalbuminemia and early congestive heart failure. Modified transudates (protein concentration < 35 g/l, cell count < 5000/l (5 x 109/l)) result from increased hydrostatic pressure (right-sided congestive heart failure, left- sided congestive heart failure in cats), decreased oncotic pressure (hypoalbuminemia) or lymphatic obstruction (neoplasia). Exudates (protein concentration > 30–35 g/l, cell count > 5000/l (5 x 109/l), are found with causes including sepsis, feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), neoplasia, lung-lobe torsion, and pancreatitis. Along with cellularity and protein content, biochemical evaluation of the fluid for creatinine, potassium, bilirubin, lactate and glucose can aid in the diagnosis of various conditions, including uroabdomen, bile peritonitis, and septic peritonitis. The equipment needed to perform an abdominocentesis includes clippers, antimicrobial scrub, 70% ethyl alcohol, sterile gloves, 18 – 22 gauge, 1 - 1 ½ inch needles, extension tubing, 20 – 60 ml syringes (depending on size of the patient), and sterile EDTA and red top tubes for sample collection. To perform an abdominocentesis, the patient is placed in left lateral (to allow the spleen to fall away from midline) or sternal recumbency. -

Guidelines for Performing Ultrasound Guided Vascular Cannulation

GUIDELINES AND STANDARDS Guidelines for Performing Ultrasound Guided Vascular Cannulation: Recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Christopher A. Troianos, MD, Gregg S. Hartman, MD, Kathryn E. Glas, MD, MBA, FASE, Nikolaos J. Skubas, MD, FASE, Robert T. Eberhardt, MD, Jennifer D. Walker, MD, and Scott T. Reeves, MD, MBA, FASE, for the Councils on Intraoperative Echocardiography and Vascular Ultrasound of the American Society of Echocardiography, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Lebanon, New Hampshire; Atlanta, Georgia; New York, New York; Boston, Massachusetts; and Charleston, South Carolina (J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:1291-318.) Keywords: Anatomy, Artery, Cannulation, Femoral, Guidelines, Internal jugular, Pediatric, Peripheral, Subclavian, Ultrasound, Vascular, Venous TABLE OF CONTENTS 7.1. Anatomic Considerations 1297 7.2. Cannulation Technique 1298 Abbreviations 1292 7.3. Complications 1298 7.4. Recommendation for IJ Vein Cannulation 1300 1. Introduction 1291 8. Subclavian Vein Cannulation 1300 2. Methodology and Evidence Review 1292 8.1. Anatomic Considerations 1300 3. Ultrasound-Guided Vascular Cannulation 1292 8.2. Cannulation Technique 1300 4. Ultrasound Principles for Needle-Guided Catheter Placement 1292 8.3. Complications 1301 5. Real-Time Imaging Versus Static Imaging 1294 8.4. Recommendation for SC Vein Cannulation 1302 6. Vessel Identification 1297 9. Femoral Vein Cannulation 1302 7. Internal Jugular Vein Cannulation 1297 9.1. Anatomic Considerations 1302 9.2. Cannulation Technique 1302 9.3. Complications 1303 From the Department of Anesthesiology, West Penn Allegheny Health System, 9.4. Recommendation for FV Cannulation 1303 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (C.A.T.); the Department of Anesthesiology, 10. Pediatric Ultrasound Guidance 1303 Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire (G.S.H.); the 10.1. -

Venous Cutdown Versus the Seldinger Technique for Placement of Totally Implantable Venous Access Ports (Protocol)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Venous cutdown versus the Seldinger technique for placement of totally implantable venous access ports (Protocol) Hsu CCT, Kwan GNC, van Driel ML, Rophael JA Hsu CCT, Kwan GNC, van Driel ML, Rophael JA. Venous cutdown versus the Seldinger technique for placement of totally implantable venous access ports. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD008942. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD008942. www.cochranelibrary.com Venous cutdown versus the Seldinger technique for placement of totally implantable venous access ports (Protocol) Copyright © 2011 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 BACKGROUND .................................... 1 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 3 METHODS ...................................... 3 REFERENCES ..................................... 5 CONTRIBUTIONSOFAUTHORS . 6 DECLARATIONSOFINTEREST . 6 SOURCESOFSUPPORT . 6 Venous cutdown versus the Seldinger technique for placement of totally implantable venous access ports (Protocol) i Copyright © 2011 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Intervention Protocol] Venous cutdown versus the Seldinger technique for placement of totally implantable venous access ports Charlie C-T Hsu1, Gigi NC Kwan2, Mieke L van Driel3, John A Rophael4 1The Alfred Hospital, Prahran, Australia. 2Box Hill Hospital, Box Hill, Australia. 3Faculty of Health -

Venaseal Closure System Product Code: VS-402

VenaSealTM Closure System Product Code: VS-402 Instructions for Use TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTENDED USE/INDICATIONS .......................................................................................... 2 3. CONTRAINDICATIONS ....................................................................................................... 2 4. WARNINGS ............................................................................................................................ 3 5. PRECAUTIONS ...................................................................................................................... 3 6. POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS OF THE DEVICE ON HEALTH ................................ 4 7. SUMMARY OF CLINICAL STUDIES ................................................................................. 5 8. PRIMARY CLINICAL STUDY (VECLOSE) ....................................................................... 5 9. HOW SUPPLIED .................................................................................................................. 16 10. STORAGE AND HANDLING ......................................................................................... 19 11. DIRECTIONS FOR USE .................................................................................................. 19 12. SYMBOL LEGEND ......................................................................................................... -

Pleural Procedures and Thoracic Ultrasound: British Thorax: First Published As 10.1136/Thx.2010.137026 on 9 August 2010

BTS guidelines Pleural procedures and thoracic ultrasound: British Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.2010.137026 on 9 August 2010. Downloaded from Thoracic Society pleural disease guideline 2010 Tom Havelock,1 Richard Teoh,2 Diane Laws,3 Fergus Gleeson,4 on behalf of the BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group < Supplementary appendices BACKGROUND curriculum for core medical training and trainees 1-4 are published online only. In hospital practice, pleural aspiration (thor- should be expected to describe the procedure and To view these files please visit acocentesis) and chest drain insertion may be complications in an examination. The trainee should the journal online (http://thorax. bmj.com). required in many different clinical settings for ensure each procedure is documented in their log a variety of indications. Doctors in most specialities book and signed by the trainer. A Directly Observed 1Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Southampton will be exposed to patients requiring pleural Practice (DOP) assessment should be completed in General Hospital, Southampton, drainage and need to be aware of safe techniques. support of this. UK There have been many reports of the dangers of Studies of training involving didactic lectures, 2Department of Respiratory large-bore chest drains and it had been anticipated manikin practice and following protocols, including Medicine, Castle Hill Hospital, that, with the previous guidelines, better training use of sedation and anaesthesia, have shown the Cottingham, East Yorkshire, UK 3Department of Thoracic and the advent of small-bore Seldinger technique risk of complications and patient pain and anxiety 4 Medicine, Royal Bournemouth chest drains, there would have been an improve- can be reduced and trainee knowledge and confi- Hospital, Bournemouth, UK ment.