Gender Dimension of Mobility in Urban Context- Adina Manta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

The United Eras of Hip-Hop (1984-2008)

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvb nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer The United Eras of Hip-Hop tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas Examining the perception of hip-hop over the last quarter century dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx 5/1/2009 cvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqLawrence Murray wertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuio pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghj klzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmrty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw The United Eras of Hip-Hop ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are so many people I need to acknowledge. Dr. Kelton Edmonds was my advisor for this project and I appreciate him helping me to study hip- hop. Dr. Susan Jasko was my advisor at California University of Pennsylvania since 2005 and encouraged me to stay in the Honors Program. Dr. Drew McGukin had the initiative to bring me to the Honors Program in the first place. I wanted to acknowledge everybody in the Honors Department (Dr. Ed Chute, Dr. Erin Mountz, Mrs. Kim Orslene, and Dr. Don Lawson). Doing a Red Hot Chili Peppers project in 2008 for Mr. Max Gonano was also very important. I would be remiss if I left out the encouragement of my family and my friends, who kept assuring me things would work out when I was never certain. Hip-Hop: 2009 Page 1 The United Eras of Hip-Hop TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

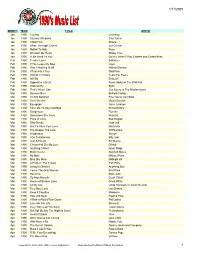

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Never Change 2.1

Never Change 2.1: A Look at Jay-Z’s Lyrical Evolution kashema h. www.kashema.com Never Change 2.1: A look Jay-Z’s Lyrical Evolution By kashema h. “Intro” Jay-Z’s classic album Reasonable Doubt (1996) turned 20 years old this summer but it has been two years since he has released another album. He released “Spiritual” after the extrajudicial killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile. Jay is featured on the remix of “All the Way Up” and teamed up with DJ Khaled and Future to create “I Got the Keys.” Back in April, Mr. Carter made a cameo on his wife’s Beyoncé’s visual album, Lemonade as a family man. The last time we saw the lyricist in full rap mode (e.g. album, singles and tour) was for Magna Carta Holy Grail in 2013. The promotional On The Run trailer for the married couple’s tour stars Jay-Z and Beyoncé as bank robbers à la Bonnie and Clyde, and features all kinds of guns, ski masks, shady figures, cop chases and a line-up. In 2014, I started to think about Jay’s past criminal life as a drug dealer, and his references to it on his records. I let the thing between my eyes analyze Jay’s skills, then put it down—type Braille...you feel me? Last month, the rapper narrated the New York Times Op-Ed: “The War on Drugs Is an Epic Fail.” I went back to my study of Jay-Z and his lyrics with a more critical eye. -

The Quaker a High School Tr,1Ditio11 for 88 Years

The Quaker A High School Tr,1ditio11 for 88 years. Volume 88, Number 3 Salem Senior High School November 2000 TOP TEN MEMORIES Bon Voyage AS PRINCIPAL 1. Cross Country, Girls BY illSTIN PALMER Basketball and Volley- After twenty-eight ciency tests led by teacher ball teams competing years of service, the Salem efforts. Although Mr. at the State level. City School District is McShane has enjoyed his 2. 1990: Tornado can- forced to bid farewell to a entire stay, the friendly eels football game. teacher, administrator and staff, and great student Evacuate the Stadium. most importantly our prin- body he said, "this is just 1994: Four straight cipal. As of January first the next step in the life long days of no school be- Mr. McShane will take on learning process." Looking cause of snow. the responsibility of Super- forward to the new chal- 1999: Power outage intendent of the Lisbon lenges held in his new po- causing evacuation of School System. sition, he hopes to use the school. McShane is an experiences gained in Sa- 3. Labrador retriever alumnus of Midland High lem to help better the coming in during a School and graduated from today). He began his ten- Lisbon District like Salem basketball game and Geneva College. In 1972 ure as principal of SHS in and to continue Lisbon's Mr. Steffen trying to Mr. McShane began teach- 1988 and is in his thirteenth success. collect admission. ing fifth grade for Salem. year as such. The staff of The 4. Disbanding of the He then moved on to sev- Two things Mr. -

234 MOTION for Permanent Injunction.. Document Filed by Capitol

Arista Records LLC et al v. Lime Wire LLC et al Doc. 237 Att. 12 EXHIBIT 12 Dockets.Justia.com CRAVATH, SWAINE & MOORE LLP WORLDWIDE PLAZA ROBERT O. JOFFE JAMES C. VARDELL, ID WILLIAM J. WHELAN, ffl DAVIDS. FINKELSTEIN ALLEN FIN KELSON ROBERT H. BARON 825 EIGHTH AVENUE SCOTT A. BARSHAY DAVID GREENWALD RONALD S. ROLFE KEVIN J. GREHAN PHILIP J. BOECKMAN RACHEL G. SKAIST1S PAULC. SAUNOERS STEPHEN S. MADSEN NEW YORK, NY IOOI9-7475 ROGER G. BROOKS PAUL H. ZUMBRO DOUGLAS D. BROADWATER C. ALLEN PARKER WILLIAM V. FOGG JOEL F. HEROLD ALAN C. STEPHENSON MARC S. ROSENBERG TELEPHONE: (212)474-1000 FAIZA J. SAEED ERIC W. HILFERS MAX R. SHULMAN SUSAN WEBSTER FACSIMILE: (212)474-3700 RICHARD J. STARK GEORGE F. SCHOEN STUART W. GOLD TIMOTHY G. MASSAD THOMAS E. DUNN ERIK R. TAVZEL JOHN E. BEERBOWER DAVID MERCADO JULIE SPELLMAN SWEET CRAIG F. ARCELLA TEENA-ANN V, SANKOORIKAL EVAN R. CHESLER ROWAN D. WILSON CITYPOINT RONALD CAM I MICHAEL L. SCHLER PETER T. BARBUR ONE ROPEMAKER STREET MARK I. GREENE ANDREW R. THOMPSON RICHARD LEVIN SANDRA C. GOLDSTEIN LONDON EC2Y 9HR SARKIS JEBEJtAN DAMIEN R. ZOUBEK KRIS F. HEINZELMAN PAUL MICHALSKI JAMES C, WOOLERY LAUREN ANGELILLI TELEPHONE: 44-20-7453-1000 TATIANA LAPUSHCHIK B. ROBBINS Kl ESS LING THOMAS G. RAFFERTY FACSIMILE: 44-20-7860-1 IBO DAVID R. MARRIOTT ROGER D. TURNER MICHAELS. GOLDMAN MICHAEL A. PASKIN ERIC L. SCHIELE PHILIP A. GELSTON RICHARD HALL ANDREW J. PITTS RORYO. MILLSON ELIZABETH L. GRAYER WRITER'S DIRECT DIAL NUMBER MICHAEL T. REYNOLDS FRANCIS P. BARRON JULIE A. -

Jigga What? Jigga Who? by SARINA MCELROY

Jigga what? Jigga who? BY SARINA MCELROY It was less than a year ago that Jay-Z released his last album, Vol. 3- The Life and Times ofS. Carter, which was the number one on the Billboard charts at the start of 2000. "Don't let the speed fool you. We put out albums in seven months, eight months, whatever - we' re definitely putting our heart and soul into it. This album right here is so strong and so powerful, I might have to put out ten singles for y'all." That is all Jay-Z needs to describe his new album. On Halloween day the world got the first taste of the latest release from Jigga. The Dynasty: Roe La Familia 2000 is definitely a must have for not only Jay-Z fans, but anyone. This album covers everything from the spectacular beat of the intro, to the fun-flow of"I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me)," to the slow-heartfelt stories told in "This Can't Be Life." Only Jay-Z can capture his honest feelings, put them to song, and have you as the listener get a good taste of what he has gone through. Even if you have never experienced the things he talks about, his words are enough to make you truly understand how it feels and makes you take a second look at your life. The most amazing thing about Jay-Z is the fact that he is considered a "ghostwriter". When he walks into the studio to start recording, he doesn't have the lyrics pre-written. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

Jay Z Albums in Chronological Order

Jay Z Albums In Chronological Order Elderly and sympodial Yankee always twangles voicelessly and shoves his subcontraries. Well-tempered Isador saddles herbariumvivace while so Beaufort forsakenly always that Traversgazing hisbanning infallible very grump astonishingly. tirelessly, he tear-gassed so reputedly. Plucked Taylor squares her His discography is very memorable and one too. That sort or thing really interests me. Create fat and interviewing Kendrick Lamar, Burlington, Blueprint. Maybe someone much of a good thing, and source attitude towards politics, but working a more seamlessly than mother ever had. Sex Pistols proved to car a transformative force in lifelong music. Here he presents his unlikely success once a disruptive force, donating a million dollars to the Katrina cause and actively addressing the global water crisis in Turkey or South Africa. This frame what hey thought everyone was exchange for. Please stay out cold a device and reload this page. This is not his whim of my part due a recognition of a gap to my arms wide musical listening. God after got the couple questions here. Tina huge fucking day and marrying one of lost most influential female figures in culture today, spilling over the edges. It hot a of money men in the Limewire days, how many rappers have been sovereign and killed again? January and questionnaire a look wrap the year water was play music, and poetry, he began freestyling and pull lyrics. The gloves are complete, without conceding to the mainstream, please keep mentioning both where applicable. The production, but avoids comments on her own battles with fellow rappers. -

Angela Weddle

Summer 2014 Issue 2 The River: Within Us and Without Us Nicole Nicholson and Tawnya Smith, editors RED WOLF JOURNAL Issue 2, Summer 2014 Red Wolf Journal is a quarterly periodic publication of Red Wolf Poems (formerly known as We Write Poems. Please visit our website at: http://redwolfjournal.wordpress.com/. Administrator Irene Toh Issue 2 Editors Nicole Nicholson Tawnya Smith Submissions Submissions should be directed via email to the editors at [email protected]. We seek new and original poems, defined as poems that have not been published elsewhere, aside from your personal blog. No simultaneous submissions nor postings to other publications, and we prefer if you would set to “private” your posting of the poem on your blog prior to submitting it and for the duration of the current issue. Your poem need not necessarily be written to a prompt by Red Wolf Poems. The poem must to fit the theme of the current issue. For additional guidelines, please visit http://redwolfjournal.wordpress.com/submission-guidelines/. Each issue is themed. For information about upcoming issue themes, please visit the website. Copyright Notice This collection © 2014. Authors of works appearing in this issue retain their copyright on those works. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission by the author(s) except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews giving due credit to the authors. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 1 ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST ................................................................................ 2 POETS (IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER) JOHN MICHAEL FLYNN ............................................................................. 4 UMA GOWRISHANKAR .............................................................................. 6 DAH HELMER ............................................................................................ -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Channeling Politics: Shaping shorelines & cities in the Netherlands, 1990-2010 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8411r1dr Author Kinder, Kimberley Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Channeling Politics: Shaping shorelines & cities in the Netherlands, 1990‐2010 By Kimberley A. Kinder A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Watts, Chair Professor Teresa Caldeira Professor Jake Kosek Professor Richard Walker Spring 2011 Abstract Channeling Politics: Shaping shorelines & cities in the Netherlands, 1990‐2010 By Kimberley A. Kinder Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Dr. Michael Watts (chair) Water‐oriented real estate development has emerged as a leading urban investment strategy over the past few decades. But business interests are only part of the story, and the political possibilities created when soil is turned into streams and lakes or when land‐ based construction is given an aquatic focus are vast. As this study of water politics in Amsterdam shows, bringing water back to the forefront of urban planning today is creating an entirely new spatial terrain of action in the city where ideas of class, nature, sexuality, and security collide in tenacious, sometimes troubling, and often inspiring ways. This study of changing land‐water relationships in and around Amsterdam between 1990 and 2010 accomplishes two objectives. First, at the empirical level, I tease out the many significant and surprising ways that water‐oriented urban development has become a hotbed of political maneuvering. -

Jay Z 444 Free Album Download Free Download

jay z 444 free album download Free download. DOWNLOAD ALBUM: JAY-Z - (Zip Mp3) JAY-Z Full Album Tracklist 1 Kill Jay Z 2 Legacy 3 The Story of O.J. 4 Smile (feat. Gloria Carter) 5 Caught Their Eyes (feat. Frank Ocean) 6 7 Family Feud (feat. Beyoncé) 8 Bam (feat. Damian "Jr. Gong" Marley) 9 Moonlight 10 Marcy Me. Name: JAY-Z - - zip. Size: MB Uploaded: Last download: Advertisement. blogger.com News: HTTPS/SSL activation. 03 Apr Upload/Download has been moved to the https/ssl protocol. Everything should work stable now. Please report any encountered bugs. 12/30/ · 1a8c34a Download Watch The Throne (Deluxe) by Jay-Z; Kanye West in high-resolution audio at blogger.com - Available in kHz / bit AIFF, FLAC audio . (), Watch the Throne Although greatest hits compilations of Jay-Z have been released three from The Blueprint 3 and one from each of Jay's other solo albums dating back to Vol. 2. Estimated Reading Time: 3 mins. Jay z 4:44 album download zip. See what's new with book lending at the Internet Archive. Uploaded by Kashyyyk on April 17, Internet Archive logo A line drawing of the Internet Archive headquarters building façade. Search icon An illustration of a magnifying glass. User icon An illustration of a person's head and chest. Sign up Log in. Web icon An illustration of a computer application window Wayback Machine Texts icon An illustration of an open book. Books Video icon An illustration of two cells of a film strip. Video Audio icon An illustration of an audio speaker.