Stream Crossing Inventories in the Swan and Notikewin River Basins of Northwest Alberta: Resolution at the Watershed Scale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

Science, Assessments and Data Availability Related to Anticipated

Science, Assessments and Data Availability Related to Anticipated Climate and Hydrologic Changes in Inland Freshwaters of the Prairies Region (Lake Winnipeg Drainage Basin) David J. Sauchyn and Jeannine-Marie St. Jacques Fisheries and Oceans Canada Freshwater Institute 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N6 2016 Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 3107 i Canadian Manuscript Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Manuscript reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which deals with national or regional problems. Distribution is restricted to institutions or individuals located in particular regions of Canada. However, no restriction is placed on subject matter, and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Manuscript reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Manuscript reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-900 in this series were issued as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Biological Board of Canada, and subsequent to 1937 when the name of the Board was changed by Act of Parliament, as Manuscript Reports (Biological Series) of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 1426 - 1550 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Manuscript Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 1551. Rapport manuscrit canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports manuscrits contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui traitent de problèmes nationaux ou régionaux. -

Distribution Alberta, North West Territories, British Columbia And

D IS TRIBUTI ON ALBERTA N ORTH E TERRITORI S BRITI S , W S T E , H COLUMB IA AN D YUKON TERRITORY CONTAINING m 1 . of Ofli The na es the Post ces alphabetically arranged . Th m o 2 . e f of C na es the Postal Car Routes , Sections Postal ar Routes or Distribution m for Offices through which atter the several offices should pass . m of m 3 . The na es the Offices to which the atter is forwarded by the Railway Mail Clerks m i di . or Distributing Offi ces when not ailed direct . (D rect Mails are in cated by dotted lines ) o 4 . The names f the Mail Routes by whi ch the offices are served when not situated on a o m line of Railway . Wh en an office is served by two or more routes the hours f departure fro the several terminal points are given . -O . m 5 ffices . Nixie List closed, na es changed — 6 . Offices in Northwest Territories Page 137 . INSTRUCTIONS for w i m l f 1 . Matter any office hich is suppl ed by ore than one route shou d be orwarded by m the one by which it will ost speedily reach its destination . i m 2 . Wh en any doubt ex sts as to the proper railway route by which atter should be f m c . orwarded, application should be ade to the District Director or Superintendent, Postal Servi e O m 3 . fli c es hi newly established, and offi ces to w ch new na es have been given , should be written in the List of Offices having the same initial letter . -

2017 Municipal Codes

2017 Municipal Codes Updated December 22, 2017 Municipal Services Branch 17th Floor Commerce Place 10155 - 102 Street Edmonton, Alberta T5J 4L4 Phone: 780-427-2225 Fax: 780-420-1016 E-mail: [email protected] 2017 MUNICIPAL CHANGES STATUS CHANGES: 0315 - The Village of Thorsby became the Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017). NAME CHANGES: 0315- The Town of Thorsby (effective January 1, 2017) from Village of Thorsby. AMALGAMATED: FORMATIONS: DISSOLVED: 0038 –The Village of Botha dissolved and became part of the County of Stettler (effective September 1, 2017). 0352 –The Village of Willingdon dissolved and became part of the County of Two Hills (effective September 1, 2017). CODE NUMBERS RESERVED: 4737 Capital Region Board 0522 Metis Settlements General Council 0524 R.M. of Brittania (Sask.) 0462 Townsite of Redwood Meadows 5284 Calgary Regional Partnership STATUS CODES: 01 Cities (18)* 15 Hamlet & Urban Services Areas (396) 09 Specialized Municipalities (5) 20 Services Commissions (71) 06 Municipal Districts (64) 25 First Nations (52) 02 Towns (108) 26 Indian Reserves (138) 03 Villages (87) 50 Local Government Associations (22) 04 Summer Villages (51) 60 Emergency Districts (12) 07 Improvement Districts (8) 98 Reserved Codes (5) 08 Special Areas (3) 11 Metis Settlements (8) * (Includes Lloydminster) December 22, 2017 Page 1 of 13 CITIES CODE CITIES CODE NO. NO. Airdrie 0003 Brooks 0043 Calgary 0046 Camrose 0048 Chestermere 0356 Cold Lake 0525 Edmonton 0098 Fort Saskatchewan 0117 Grande Prairie 0132 Lacombe 0194 Leduc 0200 Lethbridge 0203 Lloydminster* 0206 Medicine Hat 0217 Red Deer 0262 Spruce Grove 0291 St. Albert 0292 Wetaskiwin 0347 *Alberta only SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE SPECIALIZED MUNICIPALITY CODE NO. -

AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region

AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region AREA Chief Economist https://albertare.configio.com/page/ann-marie-lurie-bioAnn-Marie Lurie analyzes Alberta’s resale housing statistics both provincially and regionally. In order to allow for better analysis of housing sales data, we have aligned our reporting regions to the census divisions used by Statistics Canada. Economic Region AB-NW: Athabasca – Grande Prairie – Peace River 17 16 Economic Region AB-NE: Wood Buffalo – Cold Lake Economic Region AB-W: 19 Banff – Jasper – Rocky Mountain House 18 12 Economic Region AB-Edmonton 13 14 Economic Region AB-Red Deer 11 10 Economic Region AB-E: 9 8 7 Camrose – Drumheller 15 6 4 5 Economic Region AB-Calgary Economic Region AB-S: 2 1 3 Lethbridge – Medicine Hat New reports are released on the sixth of each month, except on weekends or holidays when it is released on the following business day. AREA Housing Statistics by Economic Region 1 Alberta Economic Region North West Grande Prairie – Athabasca – Peace River Division 17 Municipal District Towns Hamlets, villages, Other Big Lakes County - 0506 High Prairie - 0147 Enilda (0694), Faust (0702), Grouard Swan Hills - 0309 (0719), Joussard (0742), Kinuso (0189), Rural Big Lakes County (9506) Clear Hills – 0504 Cleardale (0664), Worsley (0884), Hines Creek (0150), Rural Big Lakes county (9504) Lesser Slave River no 124 - Slave Lake - 0284 Canyon Creek (0898), Chisholm (0661), 0507 Flatbush (0705), Marten Beach (0780), Smith (0839), Wagner (0649), Widewater (0899), Slave Lake (0284), Rural Slave River (9507) Northern Lights County - Manning – 0212 Deadwood (0679), Dixonville (0684), 0511 North Star (0892), Notikewin (0893), Rural Northern Lights County (9511) Northern Sunrise County - Cadotte Lake (0645), Little Buffalo 0496 (0762), Marie Reine (0777), Reno (0814), St. -

Status of the Arctic Grayling (Thymallus Arcticus) in Alberta

Status of the Arctic Grayling (Thymallus arcticus) in Alberta: Update 2015 Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 57 (Update 2015) Status of the Arctic Grayling (Thymallus arcticus) in Alberta: Update 2015 Prepared for: Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP) Alberta Conservation Association (ACA) Update prepared by: Christopher L. Cahill Much of the original work contained in the report was prepared by Jordan Walker in 2005. This report has been reviewed, revised, and edited prior to publication. It is an AEP/ACA working document that will be revised and updated periodically. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 57 (Update 2015) December 2015 Published By: i i ISBN No. 978-1-4601-3452-8 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1499-4682 (On-line Edition) Series Editors: Sue Peters and Robin Gutsell Cover illustration: Brian Huffman For copies of this report, visit our web site at: http://aep.alberta.ca/fish-wildlife/species-at-risk/ (click on “Species at Risk Publications & Web Resources”), or http://www.ab-conservation.com/programs/wildlife/projects/alberta-wildlife-status-reports/ (click on “View Alberta Wildlife Status Reports List”) OR Contact: Alberta Government Library 11th Floor, Capital Boulevard Building 10044-108 Street Edmonton AB T5J 5E6 http://www.servicealberta.gov.ab.ca/Library.cfm [email protected] 780-427-2985 This publication may be cited as: Alberta Environment and Parks and Alberta Conservation Association. 2015. Status of the Arctic Grayling (Thymallus arcticus) in Alberta: Update 2015. Alberta Environment and Parks. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 57 (Update 2015). Edmonton, AB. 96 pp. ii PREFACE Every five years, Alberta Environment and Parks reviews the general status of wildlife species in Alberta. -

Quaternary Stratigraphy and Surficial Geology Peace River Final Report

SPE 10 Quaternary Stratigraphy and Surficial Geology Peace River Final Report Alberta Energy and Utilities Board Alberta Geological Survey QUATERNARY STRATIGRAPHY AND SURFICIAL GEOLOGY PEACE RIVER - FINAL REPORT Alberta Geological Survey Special Report SPE10 (Canada – Alberta MDA Project M93-04-035) Prepared by L.E. Leslie1 and M.M. Fenton Alberta Energy and Utilities Board Alberta Geological Survey Branch 4th Floor Twin Atria Building 4999 98 Avenue Edmonton, Alberta T6B 2X3 Release date: January 2001 (1)Geo-Environmental Ltd., 169 Harvest Grove Close NE , Calgary AB T3K 4T6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Dr. B. Garrett (Geological Survey of Canada) for providing a GSC till standard to use as controls in geochemical analyses of the samples submitted to various laboratories during this study. Thanks also to R. Richardson and R. Olson for reviewing the manuscript and T. Osachuk and D. Troop of Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration regarding the Grimshaw groundwater report. The co-operation and assistance received from the personnel at Municipal Districts of 22, 131 and 135, the Peace River Alberta Transportation Regional office is sincerely appreciated. The various companies involved in locating subsurface utilities conducted through Alberta First Call were completed efficiently and without delay The writers are indebted to the willing and able support from the field assistants Solweig Balzer (1993), Nadya Slemko (1994) and Joan Marklund (1995). Special thanks also goes to Dan Magee who drafted the coloured surficial geology map. Partial funding for field support in 1994 was provided by a grant from the Canadian Circumpolar Institute. i PREFACE This report is one of the final products from a project partly funded under the Canada- Alberta Partnership Agreement on Mineral Development (Project M93-04-035) through the Mineral Development Program by what was then called the Alberta Department of Energy (now Department of Resource Development). -

Canada /Dlbsria 45 Northernriverbasins Study

ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Canada /dlbsria 4 5 3 1510 00168 6063 NorthernRiverBasins Study NORTHERN RIVER BASINS STUDY PROJECT REPORT NO. 105 CONTAMINANTS IN ENVIRONMENTAL SAMPLES: MERCURY IN THE PEACE, ATHABASCA AND SLAVE RIVER BASINS Ft A SH/177/.M45/D675/1996 Contaminants in Donald, David B 168606 DATE DUE BRODART Cat No. 23-221 ; S 8 0 2 , 0 2 / Prepared for the Northern River Basins Study under Project 5312-D1 by David B. Donald, Heather L. Craig and Jim Syrgiannis Environment Canada NORTHERN RIVER BASINS STUDY PROJECT REPORT NO. 105 CONTAMINANTS IN ENVIRONMENTAL SAMPLES: MERCURY IN THE PEACE, ATHABASCA AND SLAVE RIVER BASINS Published by the Northern River Basins Study Edmonton, Alberta ATHABASCA UNIVERSITY March, 1996 OCT 3 1 1996 LIBRARY CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Donald, David B. Contaminants in environmental samples: mercury in the Peace, Athabasca and Slave River Basins (Northern River Basins Study project report, ISSN 1192-3571 ; no. 105) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-662-24502-4 Cat. no. R71-49/3-105E 1. Mercury — Environmental aspects -- Alberta -- Athabasca River Watershed. 2. Mercury - Environmental aspects - Peace River Watershed (B.C. and Alta.) 3. Mercury - Environmental aspects -- Slave River Watershed (Alta. And N.W.T.) 4. Fishes - Effect of water pollution on - Alberta -- Athabasca River Watershed. 5. Fishes -- Effect of water pollution on -- Peace River Watershed (B.C. and Alta.) 6. Fishes — Effect of water pollution on — Slave River Watershed (Alta. And N.W.T.) I. Craig, Fleather L. II. Syrgiannis, Jim. III. Northern River Basins Study (Canada) IV. Title. V. Series. SH177.M45D62 1996 363.73'84 C96-980176-9 Copyright© 1996 by the Northern River Basins Study. -

Northern River Basins Study

Northern River Basins Study NORTHERN RIVER BASINS STUDY PROJECT REPORT NO. 133 SEDIMENT DYNAMICS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR SEDIMENT-ASSOCIATED CONTAMINANTS IN THE PEACE, ATHABASCA AND Prepared for the Northern River Basins Study under Project 5315-E1 by Michael A. Carson Consultant in Environmental Data Interpretation and Henry R. Hudson Ecological Research Division, Environment Canada NORTHERN RIVER BASINS STUDY PROJECT REPORT NO. 133 SEDIMENT DYNAMICS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR SEDIMENT-ASSOCIATED CONTAMINANTS IN THE PEACE, ATHABASCA AND SLAVE RIVER BASINS Published by the Northern River Basins Study Edmonton, Alberta March, 1997 CANADIAN CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA Carson, Michael A. Sediment dynamics and implications for sediment associated contaminants in the Peace, Athabasca and Slave River Basins (Northern River Basins Study project report, ISSN 1192-3571 ; no. 133) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-662-24768-X Cat. no. R71-49/3-133E 1. River sediments -- Environmental aspects -- Alberta - Athabasca River. 2. River sediments - Environmental aspects - Peace River (B.C. and Alta.) 3. River sediments -- Environmental aspects - Slave River (Alta, and N.W.T.) 4. Sedimentation and deposition - Environmental aspects -- Alberta -- Athabasca River. 5. Sedimentation and deposition - Environmental aspects - Peace River (B.C. and Alta.) 6. Sedimentation and deposition - Environmental aspects - Slave River (Alta, and N.W.T.) I. Hudson, H.R. (Henry Roland), 1951- II. Northern River Basins Study (Canada) III. Title. IV. Series. TD387.A43C37 1997 553.7'8'0971232 C96-980263-3 Copyright© 1997 by the Northern River Basins Study. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to reproduce all or any portion of this publication provided the reproduction includes a proper acknowledgement of the Study and a proper credit to the authors. -

Legend - AUPE Area Councils Whiskey Gap Del Bonita Coutts

Indian Cabins Steen River Peace Point Meander River 35 Carlson Landing Sweet Grass Landing Habay Fort Chipewyan 58 Quatre Fourches High Level Rocky Lane Rainbow Lake Fox Lake Embarras Portage #1 North Vermilion Settlemen Little Red River Jackfish Fort Vermilion Vermilion Chutes Fitzgerald Embarras Paddle Prairie Hay Camp Carcajou Bitumount 35 Garden Creek Little Fishery Fort Mackay Fifth Meridian Hotchkiss Mildred Lake Notikewin Chipewyan Lake Manning North Star Chipewyan Lake Deadwood Fort McMurray Peerless Lake #16 Clear Prairie Dixonville Loon Lake Red Earth Creek Trout Lake #2 Anzac Royce Hines Creek Peace River Cherry Point Grimshaw Gage 2 58 Brownvale Harmon Valley Highland Park 49 Reno Blueberry Mountain Springburn Atikameg Wabasca-desmarais Bonanza Fairview Jean Cote Gordondale Gift Lake Bay Tree #3 Tangent Rycroft Wanham Eaglesham Girouxville Spirit River Mclennan Prestville Watino Donnelly Silverwood Conklin Kathleen Woking Guy Kenzie Demmitt Valhalla Centre Webster 2A Triangle High Prairie #4 63 Canyon Creek 2 La Glace Sexsmith Enilda Joussard Lymburn Hythe 2 Faust Albright Clairmont 49 Slave Lake #7 Calling Lake Beaverlodge 43 Saulteaux Spurfield Wandering River Bezanson Debolt Wembley Crooked Creek Sunset House 2 Smith Breynat Hondo Amesbury Elmworth Grande Calais Ranch 33 Prairie Valleyview #5 Chisholm 2 #10 #11 Grassland Plamondon 43 Athabasca Atmore 55 #6 Little Smoky Lac La Biche Swan Hills Flatbush Hylo #12 Colinton Boyle Fawcett Meanook Cold Rich Lake Regional Ofces Jarvie Perryvale 33 2 36 Lake Fox Creek 32 Grand Centre Rochester 63 Fort Assiniboine Dapp Peace River Two Creeks Tawatinaw St. Lina Ardmore #9 Pibroch Nestow Abee Mallaig Glendon Windfall Tiger Lily Thorhild Whitecourt #8 Clyde Spedden Grande Prairie Westlock Waskatenau Bellis Vilna Bonnyville #13 Barrhead Ashmont St. -

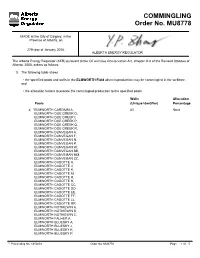

Order No. MU8778 COMMINGLING

COMMINGLING Order No. MU8778 MADE at the City of Calgary, in the Province of Alberta, on 27th day of January 2016. ALBERTA ENERGY REGULATOR The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) pursuant to the Oil and Gas Conservation Act, chapter O-6 of the Revised Statutes of Alberta, 2000, orders as follows: 1) The following table shows • the specified pools and wells in the ELMWORTH Field wherein production may be commingled in the wellbore, and • the allocation factors to prorate the commingled production to the specified pools: Wells Allocation Pools (Unique Identifier) Percentage a) 1 ELMWORTH CARDIUM A, All None ELMWORTH DOE CREEK D, ELMWORTH DOE CREEK I, ELMWORTH DOE CREEK P, ELMWORTH DOE CREEK Q, ELMWORTH DOE CREEK R, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN A, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN F, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN N, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN P, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN W, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN BB, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN MM, ELMWORTH DUNVEGAN ZZ, ELMWORTH CADOTTE A, ELMWORTH CADOTTE J, ELMWORTH CADOTTE K, ELMWORTH CADOTTE M, ELMWORTH CADOTTE R, ELMWORTH CADOTTE S, ELMWORTH CADOTTE CC, ELMWORTH CADOTTE DD, ELMWORTH CADOTTE EE, ELMWORTH CADOTTE FF, ELMWORTH CADOTTE LL, ELMWORTH CADOTTE RR, ELMWORTH NOTIKEWIN A, ELMWORTH NOTIKEWIN B, ELMWORTH NOTIKEWIN C, ELMWORTH FALHER A, ELMWORTH BLUESKY A, ELMWORTH BLUESKY J, ELMWORTH BLUESKY K, ELMWORTH BLUESKY P, (1) Proceeding No. 1850659 Order No. MU8778 Page 1 of 5 ELMWORTH BLUESKY P, ELMWORTH GETHING A, ELMWORTH GETHING H, ELMWORTH GETHING J, ELMWORTH GETHING N, ELMWORTH GETHING R, ELMWORTH GETHING EE, ELMWORTH GETHING HH, ELMWORTH NIKANASSIN K, ELMWORTH CHARLIE LAKE -

Municipalities of Alberta Lac Des Arcs CALGARY Cheadle Strathmore

122°0'0"W 121°0'0"W 120°0'0"W 119°0'0"W 118°0'0"W 117°0'0"W 116°0'0"W 115°0'0"W 114°0'0"W 113°0'0"W 112°0'0"W 111°0'0"W 110°0'0"W 109°0'0"W 108°0'0"W Fitzgerald I.D. No. 24 Wood Buffalo N " 0 ' N 0 " ° Zama City 0 ' 9 0 5 ° 9 Wood Buffalo 5 M.D. of Mackenzie No. 23 National Park Fort Chipewyan Assumption Footner Lake Rainbow Lake High Level Fort Vermilion N " 0 ' N 0 " ° 0 ' 8 La Crete 0 5 ° 8 5 Buffalo Head Prairie Paddle Prairie Regional Municipality of Keg River Wood Buffalo Carcajou M.D. of Northern Lights No. 22 N " 0 ' N 0 " ° 0 ' 7 0 5 ° 7 5 Notikewin Manning North Star M.D. of Northern Sunrise County Clear Hills No. 21 Deadwood M.D. of Fort McMurray Peerless Lake Opportunity No. 17 Worsley Dixonville Red Earth Creek Loon Lake Anzac Trout Lake Cadotte Lake Cleardale Little Buffalo Hines Creek Peace River N " Grimshaw 0 ' N 0 " ° 0 ' 6 0 5 ° M.D. of 6 5 M.D.F aoirviefw Peace No. 135 Nampa Fairview No. 136 Reno Wabasca-Desmarais Saddle Hills County Jean Cote Gift Lake Spirit River Tangent Rycroft Sandy Lake Wanham Birch Hills Girouxville M.D. of Falher Watino Spirit River County McLennan No. 133 M.D. of Conklin Woking Smoky River No. 130 Guy Grouard M.D. of Marten Beach Valhalla Centre La Glace High Prairie Enilda Lesser Slave River Sexsmith County of Joussard WidewaterWagner Canyon Creek Kinuso No.