Common Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms of the Northeast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toxic Fungi of Western North America

Toxic Fungi of Western North America by Thomas J. Duffy, MD Published by MykoWeb (www.mykoweb.com) March, 2008 (Web) August, 2008 (PDF) 2 Toxic Fungi of Western North America Copyright © 2008 by Thomas J. Duffy & Michael G. Wood Toxic Fungi of Western North America 3 Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................... 7 Dedication ............................................................................................................... 7 Preface .................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 7 An Introduction to Mushrooms & Mushroom Poisoning .............................. 9 Introduction and collection of specimens .............................................................. 9 General overview of mushroom poisonings ......................................................... 10 Ecology and general anatomy of fungi ................................................................ 11 Description and habitat of Amanita phalloides and Amanita ocreata .............. 14 History of Amanita ocreata and Amanita phalloides in the West ..................... 18 The classical history of Amanita phalloides and related species ....................... 20 Mushroom poisoning case registry ...................................................................... 21 “Look-Alike” mushrooms ..................................................................................... -

Mushrooms on Stamps

Mushrooms On Stamps Paul J. Brach Scientific Name Edibility Page(s) Amanita gemmata Poisonous 3 Amanita inaurata Not Recommended 4-5 Amanita muscaria v. formosa Poisonous (hallucenogenic) 6 Amanita pantherina Deadly Poisonous 7 Amanita phalloides Deadly Poisonous 8 Amanita rubescens Not Recommended 9-11 Amanita virosa Deadly Poisonous 12-14 Aleuria aurantiaca Edible 15 Sarcocypha coccinea Edible 16 Phlogiotis helvelloides Edible 17 Leccinum aurantiacum Good Edible 18 Boletus parasiticus Not Recommended 19 For this presentation I chose the species for Cantharellus cibarius Choice Edible 20 their occurrence in our 5 county region Cantharellus cinnabarinus Choice Edible 21 Coprinus atramentarius Poisonous 22 surrounding Rochester, NY. My intent is to Coprinus comatus Choice Edible 23 show our stamp collecting audience that an Coprinus disseminatus Edible 24 Clavulinopsis fusiformis Edible 25 artist's rendition of a fungi species depicted Leotia viscosa Harmless 26 on a stamp could be used akin to a Langermannia gigantea Choice Edible 27 Lycoperdon perlatum Good Edible 28-29 guidebook for the study of mushrooms. Entoloma murraii Not Recommended 30 Most pages depict a photograph and related Morchella esculenta Choice Edible 31-32 Russula rosacea Not Recommended (bitter) 33 stamp of the species, along with an edibility Laetiporus sulphureus Choice Edible 34 icon. Enjoy… but just the edible ones! Polyporus squamosus Edible 35 Choice/Good Edible Harmless Not Recommended Poisonous Deadly Poisonous 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Amanita rubescens (blusher) 9 10 -

Wild Mushrooms Can Kill, California Health Officer Warns Page 1 of 2

Wild Mushrooms Can Kill, California Health Officer Warns Page 1 of 2 Food Safety News - Breaking News for Everyone's Consumption Search Wild Mushrooms Can Kill, California Health Officer Warns by News Desk | Nov 26, 2011 Wild, edible mushrooms are a delectable treat but California issued a warning earlier this week to people who forage for them. Mistakes in wild mushroom identification can result in serious illness and even death, cautions Dr. Ron Chapman, director of the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) and State Public Health Officer. "It is very difficult to distinguish which mushrooms are dangerous and which are safe to eat. Therefore, we recommend that wild mushrooms not be eaten unless they have been carefully examined and determined to be edible by a mushroom expert," Chapman said. Wild mushroom poisoning continues to cause disease, hospitalization and death among California residents. According to the California Poison Control System (CPCS), 1,748 cases of mushroom ingestion were reported statewide in 2009-2010. Among those cases: - Two people died. - Ten people suffered a major health outcome, such as liver failure leading to coma and/or a liver transplant, or kidney failure requiring dialysis. - 964 were children under six years of age. These incidents usually involved the child's eating a small amount of a mushroom growing in yards or neighborhood parks. - 948 individuals were treated at a health care facility. • 19 were admitted to an intensive care unit. The most serious illnesses and deaths have been linked primarily to mushrooms known to cause liver damage, including Amanita ocreata, or "destroying angel," and Amanita phalloides, also known as the "death cap," according to the California health department's warning. -

Expansion and Diversification of the MSDIN Family of Cyclic Peptide Genes in the Poisonous Agarics Amanita Phalloides and A

Pulman et al. BMC Genomics (2016) 17:1038 DOI 10.1186/s12864-016-3378-7 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Expansion and diversification of the MSDIN family of cyclic peptide genes in the poisonous agarics Amanita phalloides and A. bisporigera Jane A. Pulman1,2, Kevin L. Childs1,2, R. Michael Sgambelluri3,4 and Jonathan D. Walton1,4* Abstract Background: The cyclic peptide toxins of Amanita mushrooms, such as α-amanitin and phalloidin, are encoded by the “MSDIN” gene family and ribosomally biosynthesized. Based on partial genome sequence and PCR analysis, some members of the MSDIN family were previously identified in Amanita bisporigera, and several other members are known from other species of Amanita. However, the complete complement in any one species, and hence the genetic capacity for these fungi to make cyclic peptides, remains unknown. Results: Draft genome sequences of two cyclic peptide-producing mushrooms, the “Death Cap” A. phalloides and the “Destroying Angel” A. bisporigera, were obtained. Each species has ~30 MSDIN genes, most of which are predicted to encode unknown cyclic peptides. Some MSDIN genes were duplicated in one or the other species, but only three were common to both species. A gene encoding cycloamanide B, a previously described nontoxic cyclic heptapeptide, was also present in A. phalloides, but genes for antamanide and cycloamanides A, C, and D were not. In A. bisporigera, RNA expression was observed for 20 of the MSDIN family members. Based on their predicted sequences, novel cyclic peptides were searched for by LC/MS/MS in extracts of A. phalloides. The presence of two cyclic peptides, named cycloamanides E and F with structures cyclo(SFFFPVP) and cyclo(IVGILGLP), was thereby demonstrated. -

Poisoning Associated with the Use of Mushrooms a Review of the Global

Food and Chemical Toxicology 128 (2019) 267–279 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food and Chemical Toxicology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodchemtox Review Poisoning associated with the use of mushrooms: A review of the global T pattern and main characteristics ∗ Sergey Govorushkoa,b, , Ramin Rezaeec,d,e,f, Josef Dumanovg, Aristidis Tsatsakish a Pacific Geographical Institute, 7 Radio St., Vladivostok, 690041, Russia b Far Eastern Federal University, 8 Sukhanova St, Vladivostok, 690950, Russia c Clinical Research Unit, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran d Neurogenic Inflammation Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran e Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Department of Chemical Engineering, Environmental Engineering Laboratory, University Campus, Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece f HERACLES Research Center on the Exposome and Health, Center for Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation, Balkan Center, Bldg. B, 10th km Thessaloniki-Thermi Road, 57001, Greece g Mycological Institute USA EU, SubClinical Research Group, Sparta, NJ, 07871, United States h Laboratory of Toxicology, University of Crete, Voutes, Heraklion, Crete, 71003, Greece ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Worldwide, special attention has been paid to wild mushrooms-induced poisoning. This review article provides a Mushroom consumption report on the global pattern and characteristics of mushroom poisoning and identifies the magnitude of mortality Globe induced by mushroom poisoning. In this work, reasons underlying mushrooms-induced poisoning, and con- Mortality tamination of edible mushrooms by heavy metals and radionuclides, are provided. Moreover, a perspective of Mushrooms factors affecting the clinical signs of such toxicities (e.g. consumed species, the amount of eaten mushroom, Poisoning season, geographical location, method of preparation, and individual response to toxins) as well as mushroom Toxins toxins and approaches suggested to protect humans against mushroom poisoning, are presented. -

Inf Information

KA´DE SPISES? 2 General advices on safe use of mushrooms • Eat only mushrooms, which you are 100% sure that you recognize Svampene kendes ofte som skadevoldere, men i naturen har de • Eat only mushrooms, which are generally recognized as edible Ka’ de spises? • Do not eat spoiled mushrooms Sådan lyder spørgsmålet igen og igen på svampeturen. Og spises overvejende uundværlige funktioner. De hjælper således med • When eating a new species of mushrooms for the first time, Ved Strandenkan 18de, mange af de vilde svampe – men bestemt ikke dem alle. til at nedbryde alt det døde materiale, så kredsløbet i naturen always start up with a small portion in order to minimize the DK-1061Copenhagen K kan fortsætte. Mange arter indgår i et samspil med planter og risk for allergy or other hypersensitivity reactions www.norden.orgIndsamling af vilde svampe åbner døren til intense naturoplevel- træer – så både svampe, træer og planter vokser bedre. Mange • Do not eat mushrooms raw, as many mushrooms may cause ser – men desværre kan manglende kendskab til svampe også svampe harinformation stor økonomisk betydning. De bruges til livsvigtig discomfort if eaten raw, e.g., stomach pain or nausea. føre til alvorlige forgiftningstilfælde ved svampespisning. De fle- medicin som antibiotikaon potential og kolesterolsænkende lægemidler, ste ved nok, at Rød Fluesvamp, der er vist på forsiden, er giftig. de anvendes i fødevareindustrien, fx som gær til brød, øl- og Especially for foreigners collecting mushrooms in the Nordic countries Den forveksles næppe med spisesvampene. Men andre giftige vinfremstilling, og man udnytter svampenes enzymer i vigtige, • Learn carefully about the mushrooms in the Nordic countries, deadly mistakes svampe er dobbeltgængere til spiselige arter. -

“All Mushrooms Are Edible; but Some Only Once.”~Croatian Proverb (Amanita Muscaria)

The Blue Ridge Poison Center Information Sheet: WILD MUSHROOMS Spring signals the start of mushroom growing season. Many wild Virginia mushrooms are edible and delicious, but some are deadly, and the differences between them may be so slight, even an experienced mycologist (mushroom scientist) can make a mistake. Mushrooms are not plants. They are the reproductive part of a fungus, an organism that “eats” dead plants and animals. The toxins in mushrooms are chemicals that are thought to have evolved to prevent animals from eating them. The toxic “Fly Agaric” “All mushrooms are edible; but some only once.”~Croatian proverb (Amanita muscaria) There are no simple guidelines to identify poisonous mushrooms. When in doubt, it is best not to eat what you have picked. Folklore presents many myths about poisonous mushrooms: MYTH: Poisonous mushrooms always have bright, flashy colors. TRUTH: Some toxic species are pure white or otherwise bland in color. MYTH: Snails, insects, or other animals won’t eat poisonous mushrooms. TRUTH: The toxins may be harmless to other organisms. Evidence that something else is eating the mushroom does not mean it is safe for humans to eat. MYTH: Toxic mushrooms turn black if touched by silver or by an onion. TRUTH: All mushrooms may darken or “bruise” as they wither or are damaged. MYTH: Toxic mushrooms smell and taste horrible. TRUTH: Some toxic mushrooms are reported to taste very good. MYTH: Any mushroom becomes safe if you cook it enough. TRUTH: Neither cooking, canning, freezing, or drying will make a poisonous mushroom safe to eat. Symptoms of mushroom poisoning are sometimes delayed by hours or even days after eating, when the toxins have begun to attack the liver and other organs. -

Amatoxin: a Review Brandon Allen, Bobby Desai* and Nathaniel Lisenbee Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA

edicine: O M p y e c n n A e c g c r Bobby Desai and Lisenbee, Emergency Medicine 2012, 2:4 e e s s m DOI: 10.4172/2165-7548.1000110 E Emergency Medicine: Open Access ISSN: 2165-7548 Review Article Open Access Amatoxin: A review Brandon Allen, Bobby Desai* and Nathaniel Lisenbee Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA Abstract This article presents a comprehensive review of amatoxin poisoning. The article discusses the biochemistry of amatoxin, as well as the clinical manifestations of amatoxin ingestion. In addition, the evaluation of the patient with amatoxin ingestion is discussed, along with the treatment – including newer therapy – and the ultimate prognosis of the syndrome. Introduction in the form of hepatic encephalopathy as seen on MRI and autopsy. The authors of this study confirmed that fulminant hepatic failure is a rapid The United States contains over 5,000 species of mushrooms. While and progressive pattern of disease that is important to understand for 4-6% of U.S. mushroom species are safe to eat, approximately 2% are any suspected amatoxin poisoning [3]. poisonous, with twelve species being known to be fatal if ingested. Worldwide, accurate figures for the incidence of mushroom toxicity Clinical Presentation are difficult to obtain. Outbreaks of severe mushroom poisoning have The pattern of injury following amatoxin ingestion presents in been documented in Europe, Russia, the Middle East, and the Far East. three phases. The first phase consists of ingestion and the appearance In all of these areas, mushroom foraging is a common practice. -

Amanita Ocreata on Vancouver Island? Theory Suggests That a Less Earth-Shaking by Shannon Berch Possibility Could Have Played a Role

Fungifama The Newsletter of the South Vancouver Island Mycological Society April 2006 Introducing the SVIMS Executive for 2006 Monthly Meetings: President Christian Freidinger [email protected] 250-721-1793 April 6: Slime! Mushrooms have it too. Vice President Speaker: Dr. Mary-Lou Florian Gerald Loiselle. [email protected] Treasurer Today fungal colonies are called Chris Shepard [email protected] biofilms because they excrete a slimy film - Membership the film of the biofilm -attached to every Andy MacKinnon [email protected] Secretary (interim) surface on which they live. The film is a buffer Joyce Lee [email protected] between the fungal structures and the 250-656-3117 environment and surface, whether it be air, Foray Organizers Adolf and Oluna Ceska [email protected] soil, rock or water. The film is the site for 250-477-1211 oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange, water Jack and Neil Greenwell [email protected] storage, enzymatic activities and protection Fungifama Editors Shannon Berch [email protected] from antibiotics and toxic metals. 250-652-5201 Heather Leary [email protected] May 4: Truffling in 250-385-2285 Publicity Spain by Shannon Joyce Lee [email protected] Berch, SVIMS, Webmaster Victoria BC Ian Gibson [email protected] 250-384-6002 Directors at large June 1: President’s Kevin Trim [email protected] Picnic - details TBD 250-642-5953 Richard Winder [email protected] Memories of the SVIMS 250-642-7528 September, 2006 Survivors Banquet Rob Gemmel [email protected] Foray, identification Refreshments Organizers Gerald and Marlee Loiselle [email protected] workshop and mushroom cookery at Sooke 250-474-4344 Harbour House organized by Kevin Trim. -

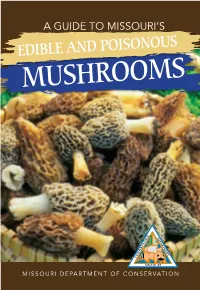

A Guide to Missouri's Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms

A GUIDE TO MISSOURI’S EDIBLE AND POISONOUS MUSHROOMS MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION A Guide to Missouri’s Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms by Malissa Briggler, Missouri Department of Conservation Content review by Patrick R. Leacock, Ph.D. Front cover: Morels are the most widely recognized edible mushroom in Missouri. They can be found throughout the state and are the inspiration of several festivals and mushroom-hunting forays. Photo by Jim Rathert. Caution! If you choose to eat wild mushrooms, safety should be your first concern. Never forget that some mushrooms are deadly, and never eat a mushroom you have not positively identified. If you cannot positively identify a mushroom you want to eat, throw it out. The author, the reviewers, the Missouri Department of Conservation, and its employees disclaim any responsibility for the use or misuse of information in this book. mdc.mo.gov Copyright © 2018 by the Conservation Commission of the State of Missouri Published by the Missouri Department of Conservation PO Box 180, Jefferson City, Missouri 65102–1080 Equal opportunity to participate in and benefit from programs of the Missouri Department of Conservation is available to all individuals without regard to their race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. Questions should be directed to the Department of Conservation, PO Box 180, Jefferson City, MO 65102, 573–751–4115 (voice) or 800–735–2966 (TTY), or to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Division of Federal Assistance, 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Mail Stop: MBSP-4020, Arlington, VA 22203. TABLE OF CONTENTS Enjoy Missouri’s Wild Mushrooms Safely .................... -

Deactivation Study of Α-Amanitin Toxicity in Poisonous Amanita Spp

orensi Narongchai and Narongchai, J Forensic Res 2017, 8:6 f F c R o e l s a e n DOI: 10.4172/2157-7145.1000396 r a r u c o h Journal of J ISSN: 2157-7145 Forensic Research Research Article Open Access Deactivation Study of α-Amanitin Toxicity in Poisonous Amanita spp. Mushrooms by the Common Substances In Vitro Paitoon Narongchai* and Siripun Narongchai Department of Forensic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, ChiangMai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand Abstract The purpose of this research was to find out the substance which deactivate α-AmanitinToxicity The materials and methods used in the study include analysis with high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to: 1.Demonstrate the standard α-amanitin at concentrations of 25, 50 and 100 µg/ml 2.Determine the deactivation of α-amanitin with 1) 18% acetic acid 2), calcium hydroxide 40 mg/ml, 3) potassium permanganate 20 mg/ml, 4) sodium bicarbonate 20 mg/ml 3.Report the statistical analysis as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and paired t-test. The result revealed that potassium permanganate could eliminate 100 percent of the α-amanitin at 25, 50 and 100 µg/ml. Calcium hydroxide, sodium bicarbonate and acetic acid had lower elimination rates at those concentrations: 68.43 ± 2.58 (-71.4, -67.2, -66.7%), 21.48 ± 10.23 (-29.4, -25.2, -9.9%) and 3.21 ± 0.02% (-3.2, -3.2, +1.1%), respectively. The conclusion of this study was suggested that potassium permanganate could be applied as an absorbent substance during gastric lavage in patients with mushroom poisoning. -

Identification of Forensically Relevant Oligopeptides of Poisonous Mushrooms with Capillary Electrophoresis-ESI-Mass Spectrometry

Identification of forensically relevant oligopeptides of poisonous mushrooms with capillary electrophoresis-ESI-mass spectrometry J. Rittgen, M. Pütz, U. Pyell Abstract Over 90% of the lethal cases of mushroom toxin poisoning in man are caused by a species of Amanita. They contain the amatoxins α-, β-, γ- and ε-amanitin, amanin and amanullin together with phallotoxins and virotoxins. The identification of the named toxicants in intentionally poisoned samples of foodstuff and beverages is of significant forensic interest. In this work a CE-ESI-MS procedure was developed for the separation of five forensically relevant oligopeptides including α-, β- and γ-amanitin, phalloidin and phallacidin. The running buffer consisted of 20 mmol/l ammonium formate at pH 10.8 and 10% (v/v) isopropanol. Dry nitrogen gas was delivered at 4 l/min at 250°C. The pressure of nebulizing nitrogen gas was set at 4 psi. The sheath liquid was isopropanol/water (50:50, v/v) at a flow rate of 3 µl/min. A mass range between 600 and 1000 m/z and negative as well as positive polarity detection mode was selected. The separation of the five negatively charged analytes was achieved at 23°C within 8 min using a high voltage of + 28 kV. The method validation included the determination of the detection limits (10 – 40 ng/ml) and the repeatability of migration time (0.2 – 0.3% RSD). The CE-MS procedure was successfully applied for the identification of amatoxins and phallotoxins in extracts of fresh and dried mushroom samples. 1. Introduction Over 90% of the lethal cases of mushroom toxin poisoning in man are caused by a species of Amanita [1].