Intranasal Steroids and the Myth of Mucosal Atrophy: a Systematic Review of Original Histological Assessments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group D07A (Corticosteroids, Plain) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 4 DISCLAIMER 6 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 7 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Methylprednisolone (ATC: D07AA01) 8 Hydrocortisone (ATC: D07AA02) 9 Prednisolone (ATC: D07AA03) 11 Clobetasone (ATC: D07AB01) 13 Hydrocortisone butyrate (ATC: D07AB02) 16 Flumetasone (ATC: D07AB03) 18 Fluocortin (ATC: D07AB04) 21 Fluperolone (ATC: D07AB05) 22 Fluorometholone (ATC: D07AB06) 23 Fluprednidene (ATC: D07AB07) 24 Desonide (ATC: D07AB08) 25 Triamcinolone (ATC: D07AB09) 27 Alclometasone (ATC: D07AB10) 29 Hydrocortisone buteprate (ATC: D07AB11) 31 Dexamethasone (ATC: D07AB19) 32 Clocortolone (ATC: D07AB21) 34 Combinations of Corticosteroids (ATC: D07AB30) 35 Betamethasone (ATC: D07AC01) 36 Fluclorolone (ATC: D07AC02) 39 Desoximetasone (ATC: D07AC03) 40 Fluocinolone Acetonide (ATC: D07AC04) 43 Fluocortolone (ATC: D07AC05) 46 2 Diflucortolone (ATC: D07AC06) 47 Fludroxycortide (ATC: D07AC07) 50 Fluocinonide (ATC: D07AC08) 51 Budesonide (ATC: D07AC09) 54 Diflorasone (ATC: D07AC10) 55 Amcinonide (ATC: D07AC11) 56 Halometasone (ATC: D07AC12) 57 Mometasone (ATC: D07AC13) 58 Methylprednisolone Aceponate (ATC: D07AC14) 62 Beclometasone (ATC: D07AC15) 65 Hydrocortisone Aceponate (ATC: D07AC16) 68 Fluticasone (ATC: D07AC17) 69 Prednicarbate (ATC: D07AC18) 73 Difluprednate (ATC: D07AC19) 76 Ulobetasol (ATC: D07AC21) 77 Clobetasol (ATC: D07AD01) 78 Halcinonide (ATC: D07AD02) 81 LIST OF AUTHORS 82 3 INTRODUCTION The availability of medicines with or without a medical prescription has implications on patient safety, accessibility of medicines to patients and responsible management of healthcare expenditure. The decision on prescription status and related supply conditions is a core competency of national health authorities. -

1532 Corticosteroids

1532 Corticosteroids olone; Ultraderm; Malaysia: Synalar†; Mex.: Cortifung-S; Cortilona; Gr.: Lidex; Ital.: Flu-21†; Topsyn; Mex.: Topsyn; Norw.: Metosyn; Pharmacopoeias. In Br. Cremisona; Farmacorti; Flumicin; Fluomex; Fusalar; Lonason; Synalar; Philipp.: Lidemol; Lidex; Singapore: Lidex†; Spain: Klariderm†; Novoter; BP 2008 (Fluocortolone Hexanoate). A white or creamy-white, Norw.: Synalar; NZ: Synalar; Philipp.: Aplosyn; Cynozet; Synalar; Syntop- Switz.: To p s y m ; To p s y m i n ; UK: Metosyn; USA: Lidex; Vanos. ic; Pol.: Flucinar; Port.: Oto-Synalar N; Synalar; Rus.: Flucinar (Флуцинар); odourless or almost odourless, crystalline powder. It exhibits pol- Multi-ingredient: Austria: Topsym polyvalent; Ger.: Jelliproct; Topsym ymorphism. Practically insoluble in water and in ether; very Sinaflan (Синафлан); S.Afr.: Cortoderm; Fluoderm; Synalar; Singapore: polyvalent; Hung.: Vipsogal†; Israel: Comagis; Mex.: Topsyn-Y; Philipp.: Flunolone-V; Spain: Co Fluocin Fuerte; Cortiespec; Fluocid Forte; Fluoder- Lidex NGN; Spain: Novoter Gentamicina; Switz.: Mycolog N; Topsym slightly soluble in alcohol and in methyl alcohol; slightly soluble mo Fuerte; Flusolgen; Gelidina; Intradermo Corticosteroi†; Synalar; Synalar polyvalent; UK: Vipsogal. in acetone and in dioxan; sparingly soluble in chloroform. Pro- Rectal Simple; Swed.: Synalar; Switz.: Synalar; Thai.: Cervicum; Flu- ciderm†; Flunolone-V; Fulone; Supralan; Synalar; UK: Synalar; USA: Capex; tect from light. Derma-Smoothe/FS; DermOtic; Fluonid; Flurosyn†; Retisert; Synalar; Syn- emol; Venez.: Bratofil; Fluquinol Simple†; Neo-Synalar; Neoflu†. Fluocortin Butyl (BAN, USAN, rINNM) ⊗ Fluocortolone Pivalate (BANM, rINNM) ⊗ Multi-ingredient: Arg.: Adop-Tar†; Tri-Luma; Austria: Myco-Synalar; Procto-Synalar; Synalar N; Belg.: Procto-Synalar; Synalar Bi-Otic; Braz.: Butil éster de la fluocortina; Butylis Fluocortinas; Fluocortine Fluocortolone, pivalate de; Fluocortolone Trimethylacetate; Dermobel†; Dermoxin; Elotin; Fluo-Vaso; Neocinolon; Otauril†; Otocort†; Butyle; SH-K-203. -

Roger M. Katz, M.D. 11500W.Olympicblvd.,Suite630 Phone:(310)393-1550 Losangeles,CA90064 Fax:(310)478-3601

Roger M. Katz, M.D. 11500W.OlympicBlvd.,Suite630 Phone:(310)393-1550 LosAngeles,CA90064 Fax:(310)478-3601 PERSONAL Date of Birth: February 23, 1938 Place of Birth: Menominee, Michigan / Marinette, Wisconsin EDUCATION 1956 Marinette High School Marinette, WI 1956 - 1960 Bachelors of Science, University of Wisconsin Madison, WI 1960 - 1961 Masters Program, University of Louisville Louisville, KY 1961 - 1965 Doctor of Medicine, University of Louisville Medical School Louisville, KY 1965 - 1967 Michael Reese Medical Center - Internship / Residency: Pediatrics Chicago, IL 1967 - 1968 David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA - Chief Resident: Los Angeles, CA Department of Pediatrics 1968 - 1970 Harbor/UCLA General Hospital - Allergy/Immunology Fellowship Los Angeles, CA 1969 - 1970 UCLA School of Public Health - Masters Program Public Health Los Angeles, CA 1969 - 1970 UCLA School of Public Health - Management Development Program Los Angeles, CA for Physicians 1996 University of Southern California - School of Business Administration Los Angeles, CA BOARD CERTIFICATION 1970 Pediatrics Certificate No. 13810 1970 Sub Board of Pediatric Allergy Certificate No. 295 1972 Allergy / Immunology Certificate No. 201 1977 Allergy / Immunology Re-Certified 1980 Pediatrics Re-Certified 1980 Pediatrics Sub Board Allergy Re-Certified HONORS Sep 1967 - Jan 1968 Chief Resident, Pediatrics David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA 1969 Travel Grant - American Academy of Allergy, 25th Annual Meeting, Bal Harbor, FL 1970 Manuscript Award: Clemens Von Perquet, "Status -

Cell Culture Spinner Flasks

Europäisches Patentamt & (19) European Patent Office Office européen des brevets (11) EP 1 736 536 A2 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 27.12.2006 Bulletin 2006/52 C12M 3/04 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 06117829.9 (22) Date of filing: 22.09.2000 (84) Designated Contracting States: • Flickinger, John AT BE CH CY DE DK ES FI FR GB GR IE IT LI LU Beverly MC NL PT SE MA 01915 (US) (30) Priority: 24.09.1999 US 405477 (74) Representative: Gill, Siân Victoria et al Venner Shipley LLP (62) Document number(s) of the earlier application(s) in 20 Little Britain accordance with Art. 76 EPC: London EC1A 7DH (GB) 00963738.0 / 1 222 248 Remarks: (71) Applicant: Cytomatrix, LLC This application was filed on 25-07-2006 as a Woburn, MA 01801 (US) divisional application to the application mentioned under INID code 62. (72) Inventors: • Upton, Todd Chestnut Hill MA 02467 (US) (54) Cell culture spinner flasks (57) The present invention relates to culturing devic- es that are compact, utilize small amounts of cell culture media to establish and maintain cell cultures, and pro- duce a large number of cells in a short period of time when compared to other cell culturing devices and tech- niques. Such devices are useful in the culture of all cell types, but are particularly useful in the culture of cells that are known in the art to be difficult to culture, including cells that lose one or more of their particular attributes/ characteristics (e.g., pluripotentiality), or cells that are difficult to establish cultures of (e.g. -

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX 4: Search Strategies Syntax Guide For

SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX 4: Search Strategies Pubmed, Embase Perioperative Management - PubMed Search Strategy – March 6, 2016 Syntax Guide for PubMed [MH] = Medical Subject Heading, also [TW] = Includes all words and numbers in known as MeSH the title, abstract, other abstract, MeSH terms, MeSH Subheadings, Publication Types, Substance Names, Personal Name as Subject, Corporate Author, Secondary Source, Comment/Correction Notes, and Other Terms - typically non-MeSH subject terms (keywords)…assigned by an organization other than NLM [SH] = a Medical Subject Heading [TIAB] = Includes words in the title and subheading, e.g. drug therapy abstracts [MH:NOEXP] = a command to retrieve the results of the Medical Subject Heading specified, but not narrower Medical Subject Heading terms Boolean Operators OR = retrieves results that include at least AND = retrieves results that include all the one of the search terms search terms NOT = excludes the retrieval of terms from the search Perioperative Management PubMed Search Strategy – March 6, 2016 Search Query #1 ((((ARTHROPLASTY, REPLACEMENT, HIP[MH] OR HIP PROSTHES*[TW] OR HIP REPLACEMENT*[TIAB] OR HIP ARTHROPLAST*[TIAB] OR HIP TOTAL REPLACEMENT*[TIAB] OR FEMORAL HEAD PROSTHES*[TIAB]) OR (ARTHROPLASTY, REPLACEMENT, KNEE[MH] OR KNEE PROSTHES*[TW] OR KNEE REPLACEMENT*[TW] OR KNEE ARTHROPLAST*[TW] OR KNEE TOTAL REPLACEMENT*[TIAB]) OR (ARTHROPLAST*[TW] AND (HIP[TIAB] OR HIPS[TIAB] OR KNEE*[TIAB])) AND (("1980/01/01"[PDAT] : "2016/03/06"[PDAT]) AND ENGLISH[LANG])) NOT (((("ADOLESCENT"[MESH]) OR "CHILD"[MESH]) -

Contact Dermatitis to Medications and Skin Products

Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology (2019) 56:41–59 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-018-8705-0 Contact Dermatitis to Medications and Skin Products Henry L. Nguyen1 & James A. Yiannias2 Published online: 25 August 2018 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Consumer products and topical medications today contain many allergens that can cause a reaction on the skin known as allergic contact dermatitis. This review looks at various allergens in these products and reports current allergic contact dermatitis incidence and trends in North America, Europe, and Asia. First, medication contact allergy to corticosteroids will be discussed along with its five structural classes (A, B, C, D1, D2) and their steroid test compounds (tixocortol-21-pivalate, triamcinolone acetonide, budesonide, clobetasol-17-propionate, hydrocortisone-17-butyrate). Cross-reactivities between the steroid classes will also be examined. Next, estrogen and testosterone transdermal therapeutic systems, local anesthetic (benzocaine, lidocaine, pramoxine, dyclonine) antihistamines (piperazine, ethanolamine, propylamine, phenothiazine, piperidine, and pyrrolidine), top- ical antibiotics (neomycin, spectinomycin, bacitracin, mupirocin), and sunscreen are evaluated for their potential to cause contact dermatitis and cross-reactivities. Finally, we examine the ingredients in the excipients of these products, such as the formaldehyde releasers (quaternium-15, 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3 diol, diazolidinyl urea, imidazolidinyl urea, DMDM hydantoin), the non- formaldehyde releasers (isothiazolinones, parabens, methyldibromo glutaronitrile, iodopropynyl butylcarbamate, and thimero- sal), fragrance mixes, and Myroxylon pereirae (Balsam of Peru) for contact allergy incidence and prevalence. Furthermore, strategies, recommendations, and two online tools (SkinSAFE and the Contact Allergen Management Program) on how to avoid these allergens in commercial skin care products will be discussed at the end. -

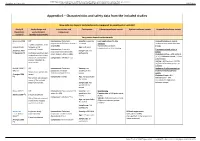

Appendix 6 – Characteristics and Safety Data from the Included Studies

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) BMJ Open Appendix 6 – Characteristics and safety data from the included studies How safe are topical corticosteroids compared to emollient or vehicle? Study ID Study design and Intervention and Participants Cutaneous adverse events Systemic adverse events Unspecified adverse events (Systematic study duration comparator review*) (Quality assessment) Very potent topical corticosteroids Breneman 2003 RCT Intervention: Clobetasol Severity: moderate Local application site skin Unspecified adverse events (1) propionate 0.05% lotion (twice a to severe reactions Incidence comparable between 2 weeks treatment, then day) (n=96) No clinically significant groups. (unpublished) followed up for Age: ≥ 12 years telangiectasia or skin thinning additional 2 weeks Intervention: Clobetasol Treatment-related adverse (Feldman 2005 Sample size: 229 propionate 0.05% emollient events (2) Nankervis (3)) Cochrane risk of bias tool: participants cream (twice a day) (n=100) Clobetasol lotion = 4/96 patients randomisation described, (4.2%); Clobetasol cream = 1/100 allocation concealment Comparator: Vehicle (n=33) patients (1%) unclear, intention-to- Vehicle = 6/33 patients (18.2%) treat unclear. (Difference between groups: p= 0.0006a) Kimball 2008 (4) RCT Intervention: Clobetasol Severity: not Incidence of adverse events or (trial a) propionate emulsion specified in the treatment related adverse Duration not specified in formulation foam 0.05% review events (Frangos 2008 review Clobetasol foam = 8% (5)) Comparator: Vehicle Age: not specified in Risk of bias not assessed Vehicle foam = 10% the review in any of the included (no significant differences systematic reviews. -

Basic Skin Care and Topical Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis

REVIEWS Basic Skin Care and Topical Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis: Essential Approaches and Beyond Sala-Cunill A1*, Lazaro M2*, Herráez L3, Quiñones MD4, Moro-Moro M5, Sanchez I6, On behalf of the Skin Allergy Committee of Spanish Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (SEAIC) 1Allergy Section, Internal Medicine Department, Hospital Universitario Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain 2Allergy Department, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Alergoasma, Salamanca, Spain 3Allergy Department, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain 4Allergy Section, Hospital Monte Naranco, Oviedo, Spain 5Allergy Department, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón, Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain 6Clínica Dermatología y Alergia, Badajoz, Spain *Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2018; Vol. 28(6): 379-391 doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0293 Abstract Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a recurrent and chronic skin disease characterized by dysfunction of the epithelial barrier, skin inflammation, and immune dysregulation, with changes in the skin microbiota and colonization by Staphylococcus aureus being common. For this reason, the therapeutic approach to AD is complex and should be directed at restoring skin barrier function, reducing dehydration, maintaining acidic pH, and avoiding superinfection and exposure to possible allergens. There is no curative treatment for AD. However, a series of measures are recommended to alleviate the disease and enable patients to improve their quality of life. These include adequate skin hydration and restoration of the skin barrier with the use of emollients, antibacterial measures, specific approaches to reduce pruritus and scratching, wet wrap applications, avoidance of typical AD triggers, and topical anti-inflammatory drugs. Anti-inflammatory treatment is generally recommended during acute flares or, more recently, for preventive management. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,544,192 B2 Eaton Et Al

US007544192B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,544,192 B2 Eaton et al. (45) Date of Patent: Jun. 9, 2009 (54) SINUS DELIVERY OF SUSTAINED RELEASE 5,443,498 A 8, 1995 Fontaine THERAPEUTICS 5,512,055 A 4/1996 Domb et al. 5,664,567 A 9, 1997 Linder (75) Inventors: Donald J. Eaton, Woodside, CA (US); 5,693,065. A 12/1997 Rains, III Mary L. Moran, Woodside, CA (US); 5,792,100 A 8/1998 Shantha Rodney Brenneman, San Juan Capistrano, CA (US) (73) Assignee: Sinexus, Inc., Palo Alto, CA (US) (Continued) (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 992 days. WO WOO1/02024 1, 2001 (21) Appl. No.: 10/800,162 (22) Filed: Mar 12, 2004 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data OTHER PUBLICATIONS US 2005/OO437O6A1 Feb. 24, 2005 Hosemann, W. et al. (Mar. 2003, e-pub. Oct. 10, 2002). “Innovative s Frontal Sinus Stent Acting as a Local Drug-Releasing System.' Eur: Related U.S. Application Data Arch. Otorhinolarynolo. 260:131-134. (60) Provisional application No. 60/454,918, filed on Mar. (Continued) 14, 2003. Primary Examiner Kevin C Sirmons (51) Int. Cl Assistant Examiner Catherine NWitczak A. iM sI/00 (2006.01) (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Morrison & Foerster LLP (52) U.S. Cl. ........................ 604/506; 604/510; 604/514 (57) ABSTRACT (58) Field of Classification Search .............. 604/93.01, 604/891.1. 890.1, 57, 59-64, 510, 514,506; S lication file f 606/196 The invention provides biodegradable implants for treating ee application file for complete search history. -

Wo 2008/127291 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (43) International Publication Date PCT (10) International Publication Number 23 October 2008 (23.10.2008) WO 2008/127291 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: Jeffrey, J. [US/US]; 106 Glenview Drive, Los Alamos, GOlN 33/53 (2006.01) GOlN 33/68 (2006.01) NM 87544 (US). HARRIS, Michael, N. [US/US]; 295 GOlN 21/76 (2006.01) GOlN 23/223 (2006.01) Kilby Avenue, Los Alamos, NM 87544 (US). BURRELL, Anthony, K. [NZ/US]; 2431 Canyon Glen, Los Alamos, (21) International Application Number: NM 87544 (US). PCT/US2007/021888 (74) Agents: COTTRELL, Bruce, H. et al.; Los Alamos (22) International Filing Date: 10 October 2007 (10.10.2007) National Laboratory, LGTP, MS A187, Los Alamos, NM 87545 (US). (25) Filing Language: English (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AT,AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY,BZ, CA, CH, (30) Priority Data: CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, 60/850,594 10 October 2006 (10.10.2006) US ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, (71) Applicants (for all designated States except US): LOS LR, LS, LT, LU, LY,MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, ALAMOS NATIONAL SECURITY,LLC [US/US]; Los MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PG, PH, PL, Alamos National Laboratory, Lc/ip, Ms A187, Los Alamos, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, SV, SY, NM 87545 (US). -

A Systematic Review of the Safety of Topical Therapies for Atopic Dermatitis J

REVIEW ARTICLE DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07538.x A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis J. Callen, S. Chamlin,* L.F. Eichenfield, C. Ellis,à M. Girardi,§ M. Goldfarb,à J. Hanifin,– P. Lee, D. Margolis,** A.S. Paller,* D. Piacquadio, W. Peterson, K. Kaulback,àà M. Fennerty– and B.U. Wintroub§§ Department of Dermatology, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, U.S.A. *Department of Dermatology, Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL, U.S.A. Department of Dermatology, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, U.S.A. àDepartment of Dermatology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, U.S.A. §Department of Dermatology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, U.S.A. –Department of Dermatology, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, OR, U.S.A. **Departments of Dermatology and Gastroenterology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A. Department of Gastroenterology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A. ààMedical Advisory Secretariat, Ministry of Health and Long Term Care, Toronto, ON, Canada §§Department of Dermatology, University of California San Francisco, 1701 Division Street, Room 338, San Francisco, CA 94143-0316, U.S.A. Summary Correspondence Background The safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis (AD), a common Bruce U. Wintroub. and morbid disease, has recently been the focus of increased scrutiny, adding E-mail: [email protected] confusion as how best to manage these patients. Objectives The objective of these systematic reviews was to determine the safety of Accepted for publication 9 June 2006 topical therapies for AD. -

BDS: CALUX Bioassays

Water safety assessment by Bioassays Cell based toxicity screening by a panel of CALUX bioassays Dr. Peter A. Behnisch Director BioDetection Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Email: [email protected] ©BDS all rights reserved Who we are BioDetection Systems B.V. (“BDS”) is a Dutch company and ISO 17025 accredited service laboratory providing biological detection systems, such as the innovative CALUX bioassays for the determination of ultra low levels of a variety of highly potent materials. Mission To provide innovative bioassays and implement their use to the highest international standards. Partner in many international projects related to water: • EC FP6 “TECHNEAU ” • Rhine Monitoring Project (RIWA) • EC FP7 ChemScreen for REACH/3Rs • Dutch Projects, z. Bsp. LEOS, ZORG, Genes4Water ©BDS all2 rights reserved CALUX ® Principles Add substrate (luciferin) LightLight measurement Toxicity via luminometer Luciferase Dioxin Proteins Endocrine Enzymes Disrupting Chemicals Transport protein Dioxin receptor Dioxin Hormonebinding Binding Hsp Dioxin Responsive Transcription Element (CRE) Nucleus Cytosol ©BDS all rights reserved 1 Panel of CALUX ® biotests • Endocrine ER AR PR KappaB nrf2 cytox p53 TR GR RAR • Acute DR KappaB p21 cytox PPAR • Repro ER AR PR TR GR RAR • Immuno DR KappaB nrf2 cytox PPAR p53 ER AR PR p21 GR RAR DR KappaB nrf2 cytox PPAR • Development ER AR PR TR GR RAR ER AR TR DR KappaB GR RAR DR nrf2 cytox KappaB PPAR p53 cytox PPAR • Muta/carcinogen p21 ©BDS all rights reserved BDS’s CALUX and typical applications (1) • DR-CALUX (dioxins, furans, PCBs, POPs, PAKs, Ah receptor ligands) • ERα-CALUX (natural, synthetic and plant-like estrogens, pseudo-estrogens, DES, endocrine disrupters, tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens) • ERβ-CALUX (like ERα-CALUX, but more for plant-like estrogens ) • AR-CALUX (androgens, anabolic steroids, pseudo- androgens, antibiotic growth promoters, nandrolone, flutamide e.a.