Contact Dermatitis to Medications and Skin Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Patent 19 11 Patent Number: 5,449,515 Hamilton Et Al

USOO5449515A United States Patent 19 11 Patent Number: 5,449,515 Hamilton et al. 45 Date of Patent: Sep. 12, 1995 (54). ANTI-INFLAMMATORY COMPOSITIONS WO9005183 5/1990 WIPO : AND METHODS OTHER PUBLICATIONS 75 Inventors: John A. Hamilton, Kew; Prudence H. Schleimer, R. P. et al., "Regulation of Human Basophil Hart, Millswood, both of Australia mediator ... ', J. Immuno., vol. 143, (4), Aug. 15, 1989, 73 Assignee: University of Melbourne, Victoria, pp. 1310-1317. Australia Hart et al., “Augmentation of Glucocorhicoid Action 21 Appl. No.: 858,967 on Human...” Lymphokine Research, vol. 9 (2), 1990, pp. 147-153. 22, PCT Filed: Nov. 21, 1990 Hart, P. H. et al., "Potential antiinflammatory effects of 86 PCT No.: PCT/AU90/00558 IL-4, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 86, pp. 3803-3807, May 1989. S 371 Date: Jul. 14, 1992 Hart, et al., Proc. Natl. AcadSci, vol. 86 pp. 3803-3807, S 102(e) Date: Jul. 14, 1992 May (1989). 87 PCT Pub. No.: WO91/07186 Primary Examiner-Michael G. Wityshyn Assistant Examiner-C. Sayala PCT Pub. Date: May 30, 1991 Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Jan P. Brunelle; Walter H. 30 Foreign Application Priority Data Dreger Nov. 21, 1989 IAU Australia ............................... PJTSO3 57 ABSTRACT 51 Int. CI.'.............................................. A61K 45/05 Therapeutic compositions and methods for the treat 52 U.S.C. .................................... 424/85.2; 530/351 ment of inflammation are disclosed. The compositions 58) Field of Search ........................ 424/85.2; 530/351 comprise at least one anti-inflammatory drug in combi nation with the lymphokine interleukin-4 (IL-4), which 56) References Cited components interact synergistically in the treatmement U.S. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2008/0317805 A1 Mckay Et Al

US 20080317805A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2008/0317805 A1 McKay et al. (43) Pub. Date: Dec. 25, 2008 (54) LOCALLY ADMINISTRATED LOW DOSES Publication Classification OF CORTICOSTEROIDS (51) Int. Cl. A6II 3/566 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: William F. McKay, Memphis, TN A6II 3/56 (2006.01) (US); John Myers Zanella, A6IR 9/00 (2006.01) Cordova, TN (US); Christopher M. A6IP 25/04 (2006.01) Hobot, Tonka Bay, MN (US) (52) U.S. Cl. .......... 424/422:514/169; 514/179; 514/180 (57) ABSTRACT Correspondence Address: This invention provides for using a locally delivered low dose Medtronic Spinal and Biologics of a corticosteroid to treat pain caused by any inflammatory Attn: Noreen Johnson - IP Legal Department disease including sciatica, herniated disc, Stenosis, mylopa 2600 Sofamor Danek Drive thy, low back pain, facet pain, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid Memphis, TN38132 (US) arthritis, osteolysis, tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, or tarsal tunnel syndrome. More specifically, a locally delivered low dose of a corticosteroid can be released into the epidural (21) Appl. No.: 11/765,040 space, perineural space, or the foramenal space at or near the site of a patient's pain by a drug pump or a biodegradable drug (22) Filed: Jun. 19, 2007 depot. E Day 7 8 Day 14 El Day 21 3OO 2OO OO OO Control Dexamethasone DexamethasOne Dexamethasone Fuocinolone Fluocinolone Fuocinolone 2.0 ng/hr 1Ong/hr 50 ng/hr 0.0032ng/hr 0.016 ng/hr 0.08 ng/hr Patent Application Publication Dec. 25, 2008 Sheet 1 of 2 US 2008/0317805 A1 900 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 80.0 - 7OO – 6OO - 5OO - E Day 7 EDay 14 40.0 - : El Day 21 2OO - OO = OO – Dexamethasone Dexamethasone Dexamethasone Fuocinolone Fluocinolone Fuocinolone 2.0 ng/hr 1Ong/hr 50 ng/hr O.OO32ng/hr O.016 ng/hr 0.08 nghr Patent Application Publication Dec. -

This Fact Sheet Provides Information to Patients with Eczema and Their Carers. About Topical Corticosteroids How to Apply Topic

This fact sheet provides information to patients with eczema and their carers. About topical corticosteroids You or your child’s doctor has prescribed a topical corticosteroid for the treatment of eczema. For treating eczema, corticosteroids are usually prepared in a cream or ointment and are applied topically (directly onto the skin). Topical corticosteroids work by reducing inflammation and helping to control an over-reactive response of the immune system at the site of eczema. They also tighten blood vessels, making less blood flow to the surface of the skin. Together, these effects help to manage the symptoms of eczema. There is a range of steroids that can be used to treat eczema, each with different strengths (potencies). On the next page, the potencies of some common steroids are shown, as well as the concentration that they are usually used in cream or ointment preparations. Using a moisturiser along with a steroid cream does not reduce the effect of the steroid. There are many misconceptions about the side effects of topical corticosteroids. However these treatments are very safe and patients are encouraged to follow the treatment regimen as advised by their doctor. How to apply topical corticosteroids How often should I apply? How much should I apply? Apply 1–2 times each day to the affected area Enough cream should be used so that the of skin according to your doctor’s instructions. entire affected area is covered. The cream can then be rubbed or massaged into the Once the steroid cream has been applied, inflamed skin. moisturisers can be used straight away if needed. -

MG40118C 1199 2H10 SEIU PDL Bifold V4 5/6/10 12:26 PM Page A

MG40118C 1199 2H10 SEIU PDL BiFold_v4 5/6/10 12:26 PM Page a 1199SEIU Preferred Drug List Please take this guide with you the next time you visit your doctor. © 2010 Medco Health Solutions, Inc. All rights reserved. Medco is a registered trademark of Medco Health Solutions, Inc. If you have questions about your prescription drug benefit, visit www.medco.com or call Medco Member Services at (800) 818-6720. For questions about your 1199SEIU benefits, call the 1199SEIU Benefit Funds’ Member Services representatives at (646) 473-9200. FPO MG40118C FPO (Ed. 4/10) Medco manages your prescription drug benefit for the 1199SEIU Benefit Funds. MG40118C 1199 2H10 SEIU PDL BiFold_v4 5/6/10 12:26 PM Page 1 This Preferred Drug List includes classes of widely used drugs that are preferred by the 1199SEIU Benefit Funds. These medications have been carefully selected to provide safety and value. If you receive any generic drug or preferred brand, you will have no out-of-pocket expense (except for GNY Benefit Fund and Rochester-area members, who may have small co-payments for certain brand-name drugs). However, if you get a nonpreferred brand when a preferred drug is available, you will be responsible for the difference in cost between the preferred and nonpreferred drugs. (Please note that this list is subject to change.) Section II provides a listing of nonpreferred brands and their possible preferred alternatives. SAFETY CONSIDERATION SYMBOLS Here is a quick guide that explains our safety symbols. These symbols appear next to certain medications. A dose lower than the manufacturer’s guidelines is often recommended for people 65 and older. -

(CD-P-PH/PHO) Report Classification/Justifica

COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE CLASSIFICATION OF MEDICINES AS REGARDS THEIR SUPPLY (CD-P-PH/PHO) Report classification/justification of medicines belonging to the ATC group D07A (Corticosteroids, Plain) Table of Contents Page INTRODUCTION 4 DISCLAIMER 6 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THIS DOCUMENT 7 ACTIVE SUBSTANCES Methylprednisolone (ATC: D07AA01) 8 Hydrocortisone (ATC: D07AA02) 9 Prednisolone (ATC: D07AA03) 11 Clobetasone (ATC: D07AB01) 13 Hydrocortisone butyrate (ATC: D07AB02) 16 Flumetasone (ATC: D07AB03) 18 Fluocortin (ATC: D07AB04) 21 Fluperolone (ATC: D07AB05) 22 Fluorometholone (ATC: D07AB06) 23 Fluprednidene (ATC: D07AB07) 24 Desonide (ATC: D07AB08) 25 Triamcinolone (ATC: D07AB09) 27 Alclometasone (ATC: D07AB10) 29 Hydrocortisone buteprate (ATC: D07AB11) 31 Dexamethasone (ATC: D07AB19) 32 Clocortolone (ATC: D07AB21) 34 Combinations of Corticosteroids (ATC: D07AB30) 35 Betamethasone (ATC: D07AC01) 36 Fluclorolone (ATC: D07AC02) 39 Desoximetasone (ATC: D07AC03) 40 Fluocinolone Acetonide (ATC: D07AC04) 43 Fluocortolone (ATC: D07AC05) 46 2 Diflucortolone (ATC: D07AC06) 47 Fludroxycortide (ATC: D07AC07) 50 Fluocinonide (ATC: D07AC08) 51 Budesonide (ATC: D07AC09) 54 Diflorasone (ATC: D07AC10) 55 Amcinonide (ATC: D07AC11) 56 Halometasone (ATC: D07AC12) 57 Mometasone (ATC: D07AC13) 58 Methylprednisolone Aceponate (ATC: D07AC14) 62 Beclometasone (ATC: D07AC15) 65 Hydrocortisone Aceponate (ATC: D07AC16) 68 Fluticasone (ATC: D07AC17) 69 Prednicarbate (ATC: D07AC18) 73 Difluprednate (ATC: D07AC19) 76 Ulobetasol (ATC: D07AC21) 77 Clobetasol (ATC: D07AD01) 78 Halcinonide (ATC: D07AD02) 81 LIST OF AUTHORS 82 3 INTRODUCTION The availability of medicines with or without a medical prescription has implications on patient safety, accessibility of medicines to patients and responsible management of healthcare expenditure. The decision on prescription status and related supply conditions is a core competency of national health authorities. -

A Note on Medical Management of Uveitis Apurupa Nedunuri Department of Pharmacology, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India

OPEN ACCESS Freely available online e Journal of Pharmacovigilance ISSN: 2329-6887 Mini Review A Note on Medical Management of Uveitis Apurupa Nedunuri Department of Pharmacology, Osmania University, Hyderabad, India ABSTRACT Uveitis is a moving illness to treat. Corticosteroids have been utilized in the treatment of uveitis for a long time. Immunosuppressives are acquiring force lately in the treatment of uveitis. In this article we present an outline of current treatment of uveitis and the significant discoveries and advances in medications and visual medication conveyance frameworks in the treatment of uveitis. Keywords: Corticosteroids; Immunosuppressives; Medical Management; Uveitis. INTRODUCTION prednisolone acetic acid derivation is multiple times less powerful on a molar premise than betamethasone or dexamethasone, the Uveitis is a potentially sight threatening disease. It may occur due entrance into the cornea of prednisolone acetic acid derivation is to an infection or may be due to an autoimmune etiology. Specific significantly more than betamethasone or dexamethasone. Dosing antimicrobial therapies with or without corticosteroids are used recurrence and the time span the medicine stays in contact with in cases of infectious uveitis. Several drugs are available for the visual surface additionally impacts adequacy. Suspensions have a management of non-infectious uveitis including corticosteroids, immunosuppressive agents, and more recently biologics. The more serious level of calming impact. treatment of uveitis is evolving -

Steroids Topical

Steroids, Topical Therapeutic Class Review (TCR) September 18, 2020 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or via any information storage or retrieval system without the express written consent of Magellan Rx Management. All requests for permission should be mailed to: Magellan Rx Management Attention: Legal Department 6950 Columbia Gateway Drive Columbia, Maryland 21046 The materials contained herein represent the opinions of the collective authors and editors and should not be construed to be the official representation of any professional organization or group, any state Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee, any state Medicaid Agency, or any other clinical committee. This material is not intended to be relied upon as medical advice for specific medical cases and nothing contained herein should be relied upon by any patient, medical professional or layperson seeking information about a specific course of treatment for a specific medical condition. All readers of this material are responsible for independently obtaining medical advice and guidance from their own physician and/or other medical professional in regard to the best course of treatment for their specific medical condition. This publication, inclusive of all forms contained herein, is intended to be educational in nature and is intended to be used for informational purposes only. Send comments and suggestions to [email protected]. September -

Classification of Medicinal Drugs and Driving: Co-Ordination and Synthesis Report

Project No. TREN-05-FP6TR-S07.61320-518404-DRUID DRUID Driving under the Influence of Drugs, Alcohol and Medicines Integrated Project 1.6. Sustainable Development, Global Change and Ecosystem 1.6.2: Sustainable Surface Transport 6th Framework Programme Deliverable 4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Due date of deliverable: 21.07.2011 Actual submission date: 21.07.2011 Revision date: 21.07.2011 Start date of project: 15.10.2006 Duration: 48 months Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: UVA Revision 0.0 Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission x Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) DRUID 6th Framework Programme Deliverable D.4.4.1 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Page 1 of 243 Classification of medicinal drugs and driving: Co-ordination and synthesis report. Authors Trinidad Gómez-Talegón, Inmaculada Fierro, M. Carmen Del Río, F. Javier Álvarez (UVa, University of Valladolid, Spain) Partners - Silvia Ravera, Susana Monteiro, Han de Gier (RUGPha, University of Groningen, the Netherlands) - Gertrude Van der Linden, Sara-Ann Legrand, Kristof Pil, Alain Verstraete (UGent, Ghent University, Belgium) - Michel Mallaret, Charles Mercier-Guyon, Isabelle Mercier-Guyon (UGren, University of Grenoble, Centre Regional de Pharmacovigilance, France) - Katerina Touliou (CERT-HIT, Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, Greece) - Michael Hei βing (BASt, Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Germany). -

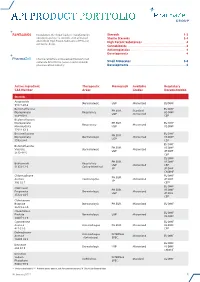

Api Product Portfolio

API PRODUCT PORTFOLIO Farmabios is the global leader in manufacturing Steroids . 1-3 nonsterile and sterile steroids, with a focused Sterile Steroids . 3-4 portfolio of High Potent Substances (HPS) and High Potent Substances . 4 anticancer drugs. Cannabinoids . 4 Antineoplastics . 4 Developments . 4 PharmaZell offers a focused portfolio of small molecule APIs for the generic and originator Small Molecules . 5-6 pharmaceutical industry. Developments . 6 Active Ingredient Therapeutic Monograph Available Regulatory CAS Number Areas Grades Documentation Steroids Amcinonide Dermatologic USP Micronized EU DMF 51022-69-6 Beclomethasone EU DMF PH.EUR. Standard Dipropionate Respiratory US DMF USP Micronized 5534-09-8 CEP Beclomethasone Dipropionate PH.EUR. EU DMF Respiratory Micronized Monohydrate USP US DMF 77011-63-3 Betamethasone EU DMF PH.EUR. Dipropionate Dermatologic Micronized US DMF USP 5593-20-4 CEP EU DMF Betamethasone PH.EUR. US DMF Valerate Dermatologic Micronized USP JP DMF 2152-44-5 CEP EU DMF PH.EUR. US DMF Budesonide Respiratory USP Micronized CEP 51333-22-3 Gastro-Intestinal JP JP DMF CN DMF Chlormadinone EU DMF PH.EUR. Acetate Contraceptive Micronized JP DMF JP 302-22-7 CEP* EU DMF Clobetasol PH.EUR. US DMF Propionate Dermatologic Micronized USP JP DMF 25122-46-7 CEP Clobetasone Butyrate Dermatologic PH.EUR. Micronized EU DMF 25122-57-0 Clocortolone EU DMF Pivalate Dermatologic USP Micronized US DMF 34097-16-0 Cyproterone EU DMF Acetate Anti-Androgen PH.EUR. Micronized US DMF 427-51-0 CEP Delmadinone Anti-Androgen INTERNAL Acetate Micronized EU DMF (Veterinary) SPEC. 13698-49-2 EU DMF Desonide Dermatologic USP Micronized US DMF 638-94-8 CN DMF Desonide Sodium INTERNAL Ophthalmic Standard EU DMF Phosphate SPEC. -

)&F1y3x PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX to THE

)&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE )&f1y3X PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 3 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. Product CAS No. Product CAS No. ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACTODIGIN 36983-69-4 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ADAFENOXATE 82168-26-1 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ADAMEXINE 54785-02-3 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ADAPALENE 106685-40-9 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ADAPROLOL 101479-70-3 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ADATANSERIN 127266-56-2 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ADEFOVIR 106941-25-7 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ADELMIDROL 1675-66-7 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 ADEMETIONINE 17176-17-9 ACAPRAZINE 55485-20-6 ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE 61-19-8 ACARBOSE 56180-94-0 ADIBENDAN 100510-33-6 ACEBROCHOL 514-50-1 ADICILLIN 525-94-0 ACEBURIC ACID 26976-72-7 ADIMOLOL 78459-19-5 ACEBUTOLOL 37517-30-9 ADINAZOLAM 37115-32-5 ACECAINIDE 32795-44-1 ADIPHENINE 64-95-9 ACECARBROMAL 77-66-7 ADIPIODONE 606-17-7 ACECLIDINE 827-61-2 ADITEREN 56066-19-4 ACECLOFENAC 89796-99-6 ADITOPRIM 56066-63-8 ACEDAPSONE 77-46-3 ADOSOPINE 88124-26-9 ACEDIASULFONE SODIUM 127-60-6 ADOZELESIN 110314-48-2 ACEDOBEN 556-08-1 ADRAFINIL 63547-13-7 ACEFLURANOL 80595-73-9 ADRENALONE -

Pdf; Chi 2015 DPP Air in Cars.Pdf; Dodson 2014 DPP Dust CA.Pdf; Kasper-Sonnenberg 2014 Phth Metabolites.Pdf; EU Cosmetics Regs 2009.Pdf

Bouge, Cathy (ECY) From: Nancy Uding <[email protected]> Sent: Friday, January 13, 2017 10:24 AM To: Steward, Kara (ECY) Cc: Erika Schreder Subject: Comments re. 2016 CSPA Rule Update - DPP Attachments: DPP 131-18-0 exposure.pdf; Chi 2015 DPP air in cars.pdf; Dodson 2014 DPP dust CA.pdf; Kasper-Sonnenberg 2014 phth metabolites.pdf; EU Cosmetics Regs 2009.pdf Please accept these comments from Toxic-Free Future concerning the exposure potential of DPP for consideration during the 2016 CSPA Rule update. Regards, Nancy Uding -- Nancy Uding Grants & Research Specialist Toxic-Free Future 206-632-1545 ext.123 http://toxicfreefuture.org 1 JES-00888; No of Pages 9 JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES XX (2016) XXX– XXX Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jes Determination of 15 phthalate esters in air by gas-phase and particle-phase simultaneous sampling Chenchen Chi1, Meng Xia1, Chen Zhou1, Xueqing Wang1,2, Mili Weng1,3, Xueyou Shen1,4,⁎ 1. College of Environmental & Resource Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China 2. Zhejiang National Radiation Environmental Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou 310011, China 3. School of Environmental and Resource Sciences, Zhejiang Agriculture and Forestry University, Hangzhou 310058, China 4. Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Organic Pollution Process and Control, Hangzhou 310058, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Based on previous research, the sampling and analysis methods for phthalate esters (PAEs) Received 24 December 2015 were improved by increasing the sampling flow of indoor air from 1 to 4 L/min, shortening the Revised 14 January 2016 sampling duration from 8 to 2 hr. -

NINDS Custom Collection II

ACACETIN ACEBUTOLOL HYDROCHLORIDE ACECLIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE ACEMETACIN ACETAMINOPHEN ACETAMINOSALOL ACETANILIDE ACETARSOL ACETAZOLAMIDE ACETOHYDROXAMIC ACID ACETRIAZOIC ACID ACETYL TYROSINE ETHYL ESTER ACETYLCARNITINE ACETYLCHOLINE ACETYLCYSTEINE ACETYLGLUCOSAMINE ACETYLGLUTAMIC ACID ACETYL-L-LEUCINE ACETYLPHENYLALANINE ACETYLSEROTONIN ACETYLTRYPTOPHAN ACEXAMIC ACID ACIVICIN ACLACINOMYCIN A1 ACONITINE ACRIFLAVINIUM HYDROCHLORIDE ACRISORCIN ACTINONIN ACYCLOVIR ADENOSINE PHOSPHATE ADENOSINE ADRENALINE BITARTRATE AESCULIN AJMALINE AKLAVINE HYDROCHLORIDE ALANYL-dl-LEUCINE ALANYL-dl-PHENYLALANINE ALAPROCLATE ALBENDAZOLE ALBUTEROL ALEXIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE ALLANTOIN ALLOPURINOL ALMOTRIPTAN ALOIN ALPRENOLOL ALTRETAMINE ALVERINE CITRATE AMANTADINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMBROXOL HYDROCHLORIDE AMCINONIDE AMIKACIN SULFATE AMILORIDE HYDROCHLORIDE 3-AMINOBENZAMIDE gamma-AMINOBUTYRIC ACID AMINOCAPROIC ACID N- (2-AMINOETHYL)-4-CHLOROBENZAMIDE (RO-16-6491) AMINOGLUTETHIMIDE AMINOHIPPURIC ACID AMINOHYDROXYBUTYRIC ACID AMINOLEVULINIC ACID HYDROCHLORIDE AMINOPHENAZONE 3-AMINOPROPANESULPHONIC ACID AMINOPYRIDINE 9-AMINO-1,2,3,4-TETRAHYDROACRIDINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMINOTHIAZOLE AMIODARONE HYDROCHLORIDE AMIPRILOSE AMITRIPTYLINE HYDROCHLORIDE AMLODIPINE BESYLATE AMODIAQUINE DIHYDROCHLORIDE AMOXEPINE AMOXICILLIN AMPICILLIN SODIUM AMPROLIUM AMRINONE AMYGDALIN ANABASAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANABASINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANCITABINE HYDROCHLORIDE ANDROSTERONE SODIUM SULFATE ANIRACETAM ANISINDIONE ANISODAMINE ANISOMYCIN ANTAZOLINE PHOSPHATE ANTHRALIN ANTIMYCIN A (A1 shown) ANTIPYRINE APHYLLIC