Mark Strand on the Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

"I Am Not Certain I Will / Keep This Word" Victoria Parker Rhode Island College, Vparker [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2016 "I Am Not Certain I Will / Keep This Word" Victoria Parker Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Poetry Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Victoria, ""I Am Not Certain I Will / Keep This Word"" (2016). Honors Projects Overview. 121. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/121 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I AM NOT CERTAIN I WILL / KEEP THIS WORD”: LOUISE GLÜCK’S REVISIONIST MYTHMAKING By Victoria Parker An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors In The Department of English Faculty of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2016 Parker 2 “I AM NOT CERTAIN I WILL / KEEP THIS WORD”: LOUISE GLÜCK’S REVISIONIST MYTHMAKING An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Victoria Parker To Department of English Approved: ___________________________________ _______________ Project Advisor Date ___________________________________ _______________ Honors Committee Chair Date ___________________________________ _______________ Department Chair Date Parker 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Five Kingdoms

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Five Kingdoms Kelle Groom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Groom, Kelle, "Five Kingdoms" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3519 FIVE KINGDOMS by KELLE GROOM M.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 B.A. University of Central Florida, 1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing/Poetry in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 Major Professor: Don Stap © 2008 Kelle Groom ii ABSTRACT GROOM, KELLE . Five Kingdoms. (Under the direction of Don Stap.) Five Kingdoms is a collection of 55 poems in three sections. The title refers to the five kingdoms of life, encompassing every living thing. Section I explores political themes and addresses subjects that reach across a broad expanse of time—from the oldest bones of a child and the oldest map of the world to the bombing of Fallujah in the current Iraq war. Connections between physical and metaphysical worlds are examined. -

Guide to the Papers of the Summer Seminar of the Arts

Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Guide to the Papers of The Summer Seminar of the Arts Auburn University at Montgomery Library Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2 Biographical Information 3-4 Scope and Content Note 5 Arrangement 5-6 Inventory 6-24 1 Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Collection Summary Creator: Jack Mooney Title: Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Dates: ca. 1969-1983 Quantity: 9 boxes; 6.0 cu. ft. Identification: 2005/02 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: Jack Mooney donated the collection to the AUM Library in May 2005. Processing By: Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant (2005). Copyright Information: Copyright not assigned to the AUM Library. Restrictions Restrictions on access: There are no restrictions on access to these papers. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. 2 Summer Seminar of the Arts Papers Biographical/Historical Information The Summer Seminar of the Arts was an annual arts and literary festival held in Montgomery from 1969 until 1983. The Seminar was part of the Montgomery Arts Guild, an organization which was active in promoting and sponsoring cultural events. Held during July, the Seminar hosted readings by notable poets, offered creative writing workshops, held creative writing contests, and featured musical performances. -

California State University, Northridge Myth in The

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE MYTH IN THE POETRY OF CHARLES SIMIC'S DISMANTLING THE SILENCE, RETURN TO A PLACE LIT BY A GLASS OF MILK, AND WHITE A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in English by Jordan Douglas Jones May 1986 The Thesis of Jordan Douglas Jones is approved: Arthur Lane, PhD Benjamin Saltman, PhD Arlene Stiebel, PhD, Chairperson Committee on Honors California State University, Northridge ii ABSTRACT MYTH IN THE POETRY OF CHARLES SIMIC'S DISMANTLING THE SILENCE, RETURN TO A PLACE LIT BY A GLASS OF MILK, AND WHITE by Jordan Douglas Jones Bachelor of Arts with Honors in English Charles Simic in the poetry of his books Dismantling the Silence, Return to a Place Lit By a Glass of Milk, and White uses myth to reach beyond the autobiographical to the archetypal and thus negate the importance of the author. In these poems, the poetic vocation mirrors the vocation of the· shaman as it has been elucidated by Mircea Eliade. Both poet and shaman allow universal forces to work through them. Simic also discusses the myths of the origins and the return to the origins of objects and works of art; as well as the dangers one must encounter when allowing uni versal creative principles to work through one during the creation of art. An~ther aspect of myth which can be seen here is the Romantic concept of Einfuhlung, or loss of ego/ iii object distinction. The author describes his union with particular natural objects. -

Penguin Anthology = of = Twentieth- Century American Poetry

SUB Hamburg 111 THE A 2011/11828 PENGUIN ANTHOLOGY = OF = TWENTIETH- CENTURY AMERICAN POETRY EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY RITA DOVE PENGUIN BOOKS Contents Introduction by Rita Dove xxix Edgar Lee Masters (1868-1950) FROM Spoon River Anthology: The Hill • 1 Fiddler Jones • 2 Petit, the Poet • 3 Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869-1935) Miniver Cheevy • 4 Mr. Flood s Party • 5 James WeldonJohnson (1871-1938) The Creation • 7 Paul Laurence Dunbar (1872-1906) 10 The Poet • 10 Life's Tragedy • 10 Robert Frost (1874-1963) 12 The Death of the Hired Man • 12 Mending Wall • 17 Birches • 18 Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening • 20 Tree at My Window • 20 Directive • 21 CONTENTS Amy Lowell (1874-1925) 23 Patterns • 23 Gertrude Stein (1874-1946) 26 Susie Asado • 26 FROM Tender Buttons: A Box • 26 A Plate • 27 Alice Moore Dunbar-Nelson (1875-1935) 28 I Sit and Sew • 28 Carl Sandburg (1878-1967) 29 Grass • 29 Cahoots • 29 Wallace Stevens (1879-1955) 31 Peter Quince at the Clavier • 31 Disillusionment of Ten O'Clock • 33 Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird • 34 Anecdote of the Jar • 36 The Emperor of Ice-Cream • 36 Of Mere Being • 36 Angelina Weld Grimke (1880-1958) 38 Fragment • 38 William Carlos Williams (1883-1963) 39 Tract • 39 DanseRusse • 41 The Red Wheelbarrow • 41 The Yachts • 42 FROM Asphodel, That Greeny Flower (Book I, lines 1-92) • 43 SaraTeasdale (1884-1933,) 51 Moonlight • 51 There Will Come Soft Rains • 51 CONTENTS Ezra Pound (1885-1972) 53 The Jewel Stairs' Grievance • 53 The River-Merchant's Wife: A Letter • 53 In a Station of the -

San José State University Department of English and Comparative Literature ENGLISH 131: Writing Poetry, Sec. 1 Fall 2014

San José State University Department of English and Comparative Literature ENGLISH 131: Writing Poetry, sec. 1 Fall 2014 Instructor: Prof. Alan Soldofsky Office Location: FO 106 Telephone: 408-924-4432 Email: [email protected] Office Hours: M, T, W 1:30 – 3:00 PM, Th PM by appointment Class Days/Time: M W 12:00 – 1:15 PM Classroom: Clark Hall 111 (Incubator Classroom) Prerequisites: ENGL 71: Introduction to Creative Writing (or equivalent); or instructor’s consent. Course Description Workshop in verse forms and poetic craft. Study of traditional and contemporary models. (May be repeated for credit.) Methods and Procedures • Students in this course will write and revise original poems, which class members will critique during the weekly in-class workshops. • Class will be divided into four student writing-groups whose members will post drafts of poems to Canvas for other members to discuss (on the Student Groups setting in Canvas). • Student Writing-Groups (one group per week) will have their members’ poems discussed in the weekly in-class workshop. • The workshop’s principal text will be class members’ original poems posted on our workshop’s Canvas and Blogger sites. • Verse forms and poetic craft will be taught through assigned readings from the required textbooks and from links to poems and commentary on the Internet. comprised of published poems, an online prosody workbook with commentaries and craft exercises, and links to poems and commentaries (sometimes including audio and video files of poets reading. • The class will be divided into 4 student writing-groups (6 or 7 students per group) to discuss first/early drafts of poems. -

September 2003 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 64, No. 5 • September, 2003 President James Shuman, PSJ Louise Glück appointed new Poet Laureate First Vice President Librarian of Congress James H. Billington has announced the appointment of Louise Jeremy Shuman, PSJ Glück as the country’s12th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. She will take up her duties Second Vice President in the fall, opening the Library’s annual literary series on October 21 with a reading of her Katharine Wilson, RF work. Glück succeeds Robert Penn Warren, Richard Wilbur, Howard Nemerov, Mark Strand, Third Vice President Pegasus Buchanan, Tw Joseph Brodsky, Mona Van Duyn, Rita Dove, Robert Hass, Robert Pinsky, Stanley Kunitz Fourth Vice President and Billy Collins. Eric Donald, Or The literary series will continue on October 22 Treasurer with a Favorite Poem reading featuring Frank Bidart Meadowlands (1996); The Wild Iris (1992), which re- Ursula Gibson, Tw and former Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky. In addition ceived the Pulitzer Prize and the Poetry Society of Recording Secretary to programming the new reading series, Glück will America’s William Carlos Williams Award; Ararat Lee Collins, Tw participate in events in February and again in May at (1990), which received the Library of Congress’s Corresponding Secretary the Library of Congress. On making the appointment, Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Poetry; Dorothy Marshall, Tw the Librarian said, “Louise Glück will bring to the and The Triumph of Achilles (1985), which received Members-at-Large Chair Library of Congress a strong, vivid, deep poetic the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Boston Frances Yordan, FG voice, accomplished in a series of book-length po- Globe Literary Press Award, and the Poetry Society etic cycles. -

A New Selected Poetry Galway Kinnell • 811.54 KI Behind My Eyes

Poetry.A selection of poetry titles from the library’s collection, in celebration of National Poetry Month in April. ** indicates that the author is a United States Poet Laureate. A New Selected Poetry ** The Collected Poems of ** The Complete Poems, Galway Kinnell • 811.54 KI Robert Lowell 1927-1979 Robert Lowell; edited by Frank Elizabeth Bishop • 811.54 BI Behind My Eyes Bidart and David Gewanter • Li-Young Lee • 811.54 LE 811.52 LO The Complete Poems William Blake • 821 BL ** The Best Of It: New and ** The Collected Poems of Selected Poems William Carlos Williams The Complete Poems Kay Ryan • 811.54 RY Edited by A. Walton Litz and Walt Whitman • 811 WH Christopher MacGowan • The Best of Ogden Nash 811 WI The Complete Poems of Edited by Linell Nash Smith • Emily Dickinson 811.52 NA The Complete Collected Poems Edited by Thomas H. Johnson • of Maya Angelou 811.54 DI The Collected Poems of Maya Angelou • 811.54 AN Langston Hughes The Complete Poems of Arnold Rampersad, editor; David Complete Poems, 1904-1962 John Keats Roessel, associate editor • E.E. Cummings; edited by John Keats • 821.7 KE 811.52 HU George J. Firmage • 811.52 CU E.E. Cummings Elizabeth Bishop William Blake Emily Dickinson Ocean City Free Public Library 1735 Simpson Avenue • Ocean City, NJ • 08226 609-399-2434 • www.oceancitylibrary.org Natasha Trethewey Pablo Neruda Robert Frost W.B. Yeats Louise Glück The Essential Haiku: Versions of Plath: Poems ** Selected Poems Basho, Buson, and Issa Sylvia Plath, selected by Diane Mark Strand • 811.54 ST Edited and with verse translations Wood by Robert Hass • 895.6 HA Middlebrook • 811.54 PL Selected Poems James Tate • 811.54 TA The Essential Rumi The Poetry of Pablo Neruda Translated by Coleman Barks, Edited and with an introduction Selected Poems with John Moyne, A.A. -

Poetry for the People

06-0001 ETF_33_43 12/14/05 4:07 PM Page 33 U.S. Poet Laureates P OETRY 1937–1941 JOSEPH AUSLANDER FOR THE (1897–1965) 1943–1944 ALLEN TATE (1899–1979) P EOPLE 1944–1945 ROBERT PENN WARREN (1905–1989) 1945–1946 LOUISE BOGAN (1897–1970) 1946–1947 KARL SHAPIRO BY (1913–2000) K ITTY J OHNSON 1947–1948 ROBERT LOWELL (1917–1977) HE WRITING AND READING OF POETRY 1948–1949 “ LEONIE ADAMS is the sharing of wonderful discoveries,” according to Ted Kooser, U.S. (1899–1988) TPoet Laureate and winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. 1949–1950 Poetry can open our eyes to new ways of looking at experiences, emo- ELIZABETH BISHOP tions, people, everyday objects, and more. It takes us on voyages with poetic (1911–1979) devices such as imagery, metaphor, rhythm, and rhyme. The poet shares ideas 1950–1952 CONRAD AIKEN with readers and listeners; readers and listeners share ideas with each other. And (1889–1973) anyone can be part of this exchange. Although poetry is, perhaps wrongly, often 1952 seen as an exclusive domain of a cultured minority, many writers and readers of WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS (1883–1963) poetry oppose this stereotype. There will likely always be debates about how 1956–1958 transparent, how easy to understand, poetry should be, and much poetry, by its RANDALL JARRELL very nature, will always be esoteric. But that’s no reason to keep it out of reach. (1914–1965) Today’s most honored poets embrace the idea that poetry should be accessible 1958–1959 ROBERT FROST to everyone. -

Louise Elisabeth Glück TEACHING EXPERIENCE

Louise Elisabeth Glück TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Stanford University, Stanford, California, Winter, 2011; 2013; 2014; 2018: MOHR PROFESSOR OF POETRY Stanford University, Stanford, California: VISITING PROFESSOR, CLASS FOR STEGNER FELLOWS Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts, Spring, 2008 – 2011: LECTURER, MFA PROGRAM Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, September, 2004 – : ROSENKRANZ WRITER IN RESIDENCE, ADJUNCT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts, January – May, 1996: HURST PROFESSOR Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, January – May, 1995: VISITING PROFESSOR (replacing Seamus Heaney) Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, September, 1984 – May, 2004 PRESTON S. PARISH ’41 THIRD CENTURY LECTURER IN ENGLISH; July, 1998 – May, 2004. Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, September, 1984 – May, 2004 SENIOR LECTURER IN ENGLISH September, 1984 – June, 1998 University of California, Los Angeles, California, April 1987, 1986, 1985: REGENTS PROFESSOR Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, September – December, 1983: SCOTT PROFESSOR OF POETRY University of California, Irvine, California, January – May, 1984: VISITING PROFESSOR University of California, Davis, California, January – March, 1983: VISITING PROFESSOR University of California, Berkeley, California, April, 1982: HOLLOWAY LECTURER Warren Wilson College, Swannanoa, North Carolina, 1980-1984: FACULTY AND BOARD MEMBER, M.F.A. Program for Writers Columbia University, New York, New York, January – May, 1979: VISITING PROFESSOR -

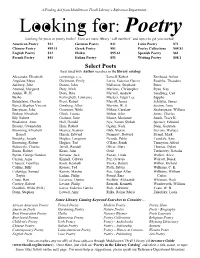

Poetry Looking for Poets Or Poetry Books? Here Are Some Library “Call Numbers” and Topics to Get You Started!

A Finding Aid from Middletown Thrall Library’s Reference Department… Looking for: Poetry Looking for poets or poetry books? Here are some library “call numbers” and topics to get you started! American Poetry 811 German Poetry 831 Latin Poetry 871 Chinese Poetry 895.11 Greek Poetry 881 Poetry Collections 808.81 English Poetry 812 Haiku 895.61 Spanish Poetry 861 French Poetry 841 Italian Poetry 851 Writing Poetry 808.1 Select Poets (best used with Author searches in the library catalog) Alexander, Elizabeth cummings, e. e. Lowell, Robert Rimbaud, Arthur Angelou, Maya Dickinson, Emily Lorca, Federico Garcia Roethke, Theodore Ashbery, John Donne, John Mallarme, Stephane Rumi Atwood, Margaret Doty, Mark Marlowe, Christopher Ryan, Kay Auden, W. H. Dove, Rita Marvell, Andrew Sandburg, Carl Basho Ferlinghetti, Lawrence Masters, Edgar Lee Sappho Baudelaire, Charles Frost, Robert Merrill, James Schuyler, James Benet, Stephen Vincent Ginsberg, Allen Merwin, W. S. Sexton, Anne Berryman, John Giovanni, Nikki Milosz, Czeslaw Shakespeare, William Bishop, Elizabeth Gluck, Louise Milton, John Simic, Charles Bly, Robert Graham, Jorie Moore, Marianne Smith, Tracy K. Bradstreet, Anne Hall, Donald Nye, Naomi Shihab Spenser, Edmund Brooks, Gwendolyn Hass, Robert Ogden, Nash Stein, Gertrude Browning, Elizabeth Heaney, Seamus Olds, Sharon Stevens, Wallace Barrett Hirsch, Edward Nemerov, Howard Strand, Mark Brodsky, Joseph Hughes, Langston Neruda, Pablo Teasdale, Sara Browning, Robert Hughes, Ted O'Hara, Frank Tennyson, Alfred Bukowski, Charles Jarrell, Randall Oliver, Mary Thomas, Dylan Burns, Robert Keats, John Ovid Trethewey, Natasha Byron, George Gordon Kerouac, Jack Pastan, Linda Walker, Alice Carson, Anne Kinnell, Galway Paz, Octavio Walcott, Derek Chaucer, Geoffrey Koch, Kenneth Pinsky, Robert Wilbur, Richard Collins, Billy Kooser, Ted Plath, Sylvia Williams, C.