Four Quarters Volume 21 Article 1 Number 4 Four Quarters: May 1972 Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

April 2005 Updrafts

Chaparral from the California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving Californiaupdr poets for over 60 yearsaftsVolume 66, No. 3 • April, 2005 President Ted Kooser is Pulitzer Prize Winner James Shuman, PSJ 2005 has been a busy year for Poet Laureate Ted Kooser. On April 7, the Pulitzer commit- First Vice President tee announced that his Delights & Shadows had won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. And, Jeremy Shuman, PSJ later in the week, he accepted appointment to serve a second term as Poet Laureate. Second Vice President While many previous Poets Laureate have also Katharine Wilson, RF Winners of the Pulitzer Prize receive a $10,000 award. Third Vice President been winners of the Pulitzer, not since 1947 has the Pegasus Buchanan, Tw prize been won by the sitting laureate. In that year, A professor of English at the University of Ne- braska-Lincoln, Kooser’s award-winning book, De- Fourth Vice President Robert Lowell won— and at the time the position Eric Donald, Or was known as the Consultant in Poetry to the Li- lights & Shadows, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2004. Treasurer brary of Congress. It was not until 1986 that the po- Ursula Gibson, Tw sition became known as the Poet Laureate Consult- “I’m thrilled by this,” Kooser said shortly after Recording Secretary ant in Poetry to the Library of Congress. the announcement. “ It’s something every poet dreams Lee Collins, Tw The 89th annual prizes in Journalism, Letters, of. There are so many gifted poets in this country, Corresponding Secretary Drama and Music were announced by Columbia Uni- and so many marvelous collections published each Dorothy Marshall, Tw versity. -

When Is an Agrarian Not an Agrarian? a Reading of Robert Penn Warren’S “The Rb Iar Patch” Clare Byrne

Robert Penn Warren Studies Volume 10 Robert Penn Warren Studies Article 2 2016 When Is an Agrarian Not an Agrarian? A Reading of Robert Penn Warren’s “The rB iar Patch” Clare Byrne Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies Part of the American Literature Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Byrne, Clare (2016) "When Is an Agrarian Not an Agrarian? A Reading of Robert Penn Warren’s “The rB iar Patch”," Robert Penn Warren Studies: Vol. 10 , Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/rpwstudies/vol10/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Penn Warren Studies by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When Is an Agrarian Not an Agrarian? A Reading of Robert Penn Warren’s “The Briar Patch” Clare Byrne King’s College, London Critics have tended to fall into one of two camps on the matter of Robert Penn Warren’s participation in the Southern Agrarian movement. They have either agreed with Hugh Ruppersburg that “Agrarianism is…the essential premise on which [Warren’s] American explorations have rested” (30), or with Paul Conkin that “never” did Warren “ever write a single essay in which he committed himself, philosophically, to any version of Agrarian ideology” (105). As a result, his literary output has often either been read as a direct expression of Southern Agrarianism, or exonerated from any connection to it. I propose that Warren’s relationship to Agrarianism was much more complex and conflicted than either of these positions allows, and that this is evident even in the essays he explicitly contributed to the movement. -

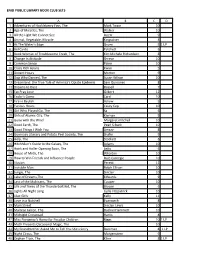

Web Book Club Sets

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

"I Am Not Certain I Will / Keep This Word" Victoria Parker Rhode Island College, Vparker [email protected]

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC Honors Projects Overview Honors Projects 2016 "I Am Not Certain I Will / Keep This Word" Victoria Parker Rhode Island College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects Part of the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Poetry Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Victoria, ""I Am Not Certain I Will / Keep This Word"" (2016). Honors Projects Overview. 121. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/honors_projects/121 This Honors is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Projects at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects Overview by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “I AM NOT CERTAIN I WILL / KEEP THIS WORD”: LOUISE GLÜCK’S REVISIONIST MYTHMAKING By Victoria Parker An Honors Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors In The Department of English Faculty of Arts and Sciences Rhode Island College 2016 Parker 2 “I AM NOT CERTAIN I WILL / KEEP THIS WORD”: LOUISE GLÜCK’S REVISIONIST MYTHMAKING An Undergraduate Honors Project Presented By Victoria Parker To Department of English Approved: ___________________________________ _______________ Project Advisor Date ___________________________________ _______________ Honors Committee Chair Date ___________________________________ _______________ Department Chair Date Parker 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS -

Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: the Growth of Consciousness

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1979 Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: The Growth of Consciousness. Alexander George Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation George, Alexander, "Philip Roth's Confessional Narrators: The Growth of Consciousness." (1979). Dissertations. 1823. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1823 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1979 Alexander George PHILIP ROTH'S CONFESSIONAL NARRATORS: THE GROWTH OF' CONSCIOUSNESS by Alexander George A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1979 ACKNOWLEDGE~£NTS It is a singular pleasure to acknowledge the many debts of gratitude incurred in the writing of this dissertation. My warmest thanks go to my Director, Dr. Thomas Gorman, not only for his wise counsel and practical guidance, but espec~ally for his steadfast encouragement. I am also deeply indebted to Dr. Paul Messbarger for his careful reading and helpful criticism of each chapter as it was written. Thanks also must go to Father Gene Phillips, S.J., for the benefit of his time and consideration. I am also deeply grateful for the all-important moral support given me by my family and friends, especially Dr. -

Hip to Post45

DAVID J. A L WORTH Hip to Post45 Michael Szalay, Hip Figures: A Literary History of the Democratic Party. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012. 324 pp. $24.95. here are we now?” About five years [ ] have passed since Amy Hungerford “ W asked this question in her assess- ment of the “revisionary work” that was undertaken by literary historians at the dawn of the twenty- first century.1 Juxtaposing Wendy Steiner’s contribution to The Cambridge History of American Literature (“Postmodern Fictions, 1970–1990”) with new scholarship by Rachel Adams, Mark McGurl, Deborah Nelson, and others, Hungerford aimed to demonstrate that “the period formerly known as contemporary” was being redefined and revitalized in exciting new ways by a growing number of scholars, particularly those associated with Post45 (410). Back then, Post45 named but a small “collective” of literary historians, “mainly just finishing first books or in the middle of second books” (416). Now, however, it designates something bigger and broader, a formidable institution dedi- cated to the study of American culture during the second half of the twentieth century and beyond. This institution comprises an ongoing sequence of academic conferences (including a large 1. Amy Hungerford, “On the Period Formerly Known as Contemporary,” American Literary History 20.1–2 (2008) 412. Subsequent references will appear in the text. Contemporary Literature 54, 3 0010-7484; E-ISSN 1548-9949/13/0003-0622 ᭧ 2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System ALWORTH ⋅ 623 gathering that took place at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2011), a Web-based journal of peer-reviewed scholarship and book reviews (Post45), and a monograph series published by Stanford University Press (Post•45). -

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3. -

Five Kingdoms

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 Five Kingdoms Kelle Groom University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Groom, Kelle, "Five Kingdoms" (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3519. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3519 FIVE KINGDOMS by KELLE GROOM M.A. University of Central Florida, 1995 B.A. University of Central Florida, 1989 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing/Poetry in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2008 Major Professor: Don Stap © 2008 Kelle Groom ii ABSTRACT GROOM, KELLE . Five Kingdoms. (Under the direction of Don Stap.) Five Kingdoms is a collection of 55 poems in three sections. The title refers to the five kingdoms of life, encompassing every living thing. Section I explores political themes and addresses subjects that reach across a broad expanse of time—from the oldest bones of a child and the oldest map of the world to the bombing of Fallujah in the current Iraq war. Connections between physical and metaphysical worlds are examined. -

University of Regina Archives and Special Collections The

UNIVERSITY OF REGINA ARCHIVES AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS THE DR JOHN ARCHER LIBRARY 2012-35 JOAN GIVNER RESARCH AND WRITING ON KATHERINE ANNE PORTER JULY 2012 BY CHELSEA SCHESKE, LYDIA MILIOKAS, ELIZABETH SEITZ AND MICHELLE OLSON REVISED MARCH 2016 BY ELIZABETH SEITZ 2012-35 JOAN GIVNER 2 / 12 Biographical Sketch: Joan Givner (nee Short) graduated from the University of London with a Bachelor of Arts Honours degree in 1958 and a Ph.D. in 1972. She earned a Masters degree in Arts from Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri in 1965. While in the United States she taught high school from 1959 until 1961. She then taught English at Port Huron Junior College (now St Clair County Community College) from 1961 until 1965. Givner joined the predecessor of the University of Regina, the University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus, as a Lecturer of English in 1965 and in 1972 became an Assistant Professor, in 1975 an Associate Professor and in 1981 she became a Professor of English. Joan retired from the University of Regina in 1995 to Victoria, British Columbia and taught creative writing at Malaspina College – Cowichan Campus during the spring of 1997. Joan Givner’s Ph.D. thesis is titled A Critical Study of the Worlds of Katherine Anne Porter (1972), since then, Joan was chosen by Katherine Anne Porter to undertake the task of writing Porter’s biography. Katherine Anne Porter: A Life was published in 1982. Other publications by Givner are Tentacles of Unreason (1985), Katherine Anne Porter: Conversations (1987); Unfortunate Incidents (1988), Mazo de la Roche: The Hidden Life (1989), Katherine Anne Porter: A Life (Revised Edition) (1991), Scenes from Provincial Life (1991), The Self-Portrait of a Literary Biographer (1993), In the Garden of Henry James (1996), Thirty-four Ways of Looking at Jane Eyre: Essays and Fiction (1998) and Half Known Lives (2000). -

Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Technology Faculty Publications Jan. 2015) 2013 Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix Chara Haeussler Bohan Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_facpub Part of the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Nix, J. & Bohan, C. H. (2013). Reaching across the color line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an uncommon friendship. Social Education, 77(3), 127–131. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Jan. 2015) at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Education 77(3), pp 127–131 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Reaching across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix and Chara Haeussler Bohan In 1940, Atlanta was a bustling town. It was still dazzling from the glow of the previous In Atlanta, the color line was clearly year’s star-studded premiere of Gone with the Wind. The city purchased more and drawn between black and white citizens.