Journalists in Film: Heroes and Villains Brian Mcnair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Interviews Stone on Stone Between 2010 and 2014 we interviewed Oliver Stone on a number of occasions, either personally or in correspondence by email. He was always ready to engage with us, quite literally. Stone thrives on the cut- and- thrust of debate about his films, about himself and per- ceptions of him that have adorned media outlets around the world throughout his career – and, of course, about the state of America. What follows are transcripts from some of those interviews, with- out redaction. Stone is always at his most fascinating when a ques- tion leads him down a line of theory or thinking that can expound on almost any topic to do with his films, or with the issues in the world at large. Here, that line of thinking appears on the page as he spoke, and gives credence to the notion of a filmmaker who, whether loved or loathed, admired or admonished, is always ready to fight his corner and battle for what he believes is a worthwhile, even noble, cause. Oliver Stone’s career has been defined by battle and the will to overcome criticism and or adversity. The following reflections demonstrate why he remains the most talked about, and combative, filmmaker of his generation. Interview with Oliver Stone, 19 January 2010 In relation to the Classification and Ratings Administration Interviewer: How do you see the issue of cinematic censorship? Oliver Stone: The ratings thing is very much a limited game. If you talk to Joan Graves, you’ll get the facts. The rules are the rules. -

Exhibits Registrations

July ‘09 EXHIBITS In the Main Gallery MONDAY TUESDAY SATURDAY ART ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBERS’ 6 14 “STREET ANGEL” (1928-101 min.). In HYPERTENSION SCREENING: Free 18 SHOW, throughout the summer. AAC MANHASSET BAY BOAT TOURS: Have “laughter-loving, careless, sordid Naples,” screening by St. Francis Hospital. 11 a.m. a look at Manhasset Bay – from the water! In the Photography Gallery a fugitive named Angela (Oscar winner to 2 p.m. A free 90-minute boat tour will explore Janet Gaynor) joins a circus and falls in Legendary Long the history and ecology of our corner of love with a vagabond painter named Gino TOPICAL TUESDAY: Islanders. What do Billy Joel, Martha Stew- Long Island Sound. Tour dates are July (Charles Farrell). Philip Klein and Henry art, Kiri Te Kanawa and astronaut Dr. Mary 18; August 8 and 29. The tour is free, but Roberts Symonds scripted, from a novel Cleave have in common? They have all you must register at the Information Desk by Monckton Hoffe, for director Frank lived on Long Island and were interviewed for the 30 available seats. Registration for Borzage. Ernest Palmer and Paul Ivano by Helene Herzig when she was feature the July 18 tour begins July 2; Registration provided the glistening cinematography. editor of North Shore Magazine. Herzig has for the August tours begins July 21. Phone Silent with orchestral score. 7:30 p.m. collected more than 70 of her interviews, registration is acceptable. Tours at 1 and written over a 20-year period. The celebri- 3 p.m. Call 883-4400, Ext. -

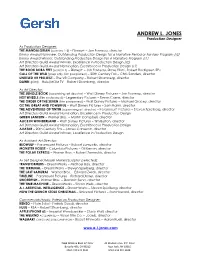

JONES-A.-RES-1.Pdf

ANDREW L. JONES Production Designer As Production Designer: THE MANDALORIAN (seasons 1-3) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, director Emmy Award Nominee, Outstanding Production Design for a Narrative Period or Fantasy Program (s2) Emmy Award Winner, Outstanding Production Design For A Narrative Program (s1) Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design (s2) Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design (s1) THE BOOK BOBA FETT (season 1) – Disney+ – Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, Robert Rodriguez, EPs CALL OF THE WILD (prep only, film postponed) – 20th Century Fox – Chris Sanders, director UNTITLED VR PROJECT – The VR Company – Robert Stromberg, director DAWN (pilot) – Hulu/MGM TV – Robert Stromberg, director As Art Director: THE JUNGLE BOOK (supervising art director) – Walt Disney Pictures – Jon Favreau, director HOT WHEELS (film postponed) – Legendary Pictures – Simon Crane, director THE ORDER OF THE SEVEN (film postponed) – Walt Disney Pictures – Michael Gracey, director OZ THE GREAT AND POWERFUL – Walt Disney Pictures – Sam Raimi, director THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN (supervising art director) – Paramount Pictures – Steven Spielberg, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design GREEN LANTERN – Warner Bros. – Martin Campbell, director ALICE IN WONDERLAND – Walt Disney Pictures – Tim Burton, director Art Directors Guild Award Nomination, Excellence in Production Design AVATAR – 20th Century Fox – James Cameron, director Art Directors Guild Award Winner, Excellence in Production Design As Assistant Art Director: BEOWULF – Paramount Pictures – Robert Zemeckis, director MONSTER HOUSE – Columbia Pictures – Gil Kenan, director THE POLAR EXPRESS – Warner Bros. – Robert Zemeckis, director As Set Designer/Model Maker/Sculptor (selected): TRANSFORMERS – DreamWorks – Michael Bay, director THE TERMINAL – DreamWorks – Steven Spielberg, director THE LAST SAMURAI – Warner Bros. -

Audio Describing the Exposition Phase of Films

TRANS · núm. 11 · 2007 La audiodescripción se está introduciendo progresivamente en los productos DOSSIER · 73-93 audiovisuales y esto tiene como resultado por una parte la necesidad de formar a los futuros audiodescriptores y, por otra parte, formar a los formadores con unas herramientas adecuadas para enseñar cómo audiodescribir. No cabe la menor que como documento de partida para la formación las guías y normas de audiodescripción existentes son de una gran utilidad, sin embargo, éstas no son perfectas ya que no ofrecen respuestas a algunas cuestiones esenciales como qué es lo que se debe describir cuando no se cuenta con el tiempo suficiente para describir todo lo que sucede. El presente artículo analiza una de las cuestiones que normalmente no responden las guías o normas: qué se debe priorizar. Se demostrará cómo una profundización en la narrativa de películas y una mejor percepción de las pistas visuales que ofrece el director puede ayudar a decidir la información que se recoge. Los fundamentos teóricos expuestos en la primera parte del artículo se aplicarán a la secuencia expositiva de la película Ransom. PALABRAS CALVE: audiodescripción, accesibilidad, traducción audiovisual. Audio describing the exposition phase of films. Teaching students what to choose Ever more countries are including audio description (AD) in their audiovisual products, which results on the one hand in a need for training future describers and on the other in a need to provide trainers with adequate tools for teaching. Existing AD guidelines are undoubtedly valuable instruments for beginning audio describers, but they are not perfect in that they do not provide answers to certain essential questions, such as what should be described in situations where it is impossible to describe everything that can be seen. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Oliver Stone Et Woody Allen Sèment Le Bonheur Sur La Croisette

Culture / Culture FESTIVAL DE CANNES Oliver Stone et Woody Allen sèment le bonheur sur la Croisette Les deux cinéastes américains, Oliver Stone et Woody Allen, qui ont présenté leur dernier film, respectivement, Wall Street : l'argent ne dort jamais, suite du filmWall Street, sorti en 1988, et You will meet a tall dark stranger, les deux présentés en Hors Compétition, ont ravi la vedette aux cinéastes en lice pour la plus haute distinction du festival : la Palme d'or. Commençons par Oliver Stone. Fidèle à lui-même, et toujours à l'avant-garde, il a exploré et dénoncé la dictature impitoyable de l'argent, imposée par les spéculateurs et grands banquiers de Wall Street. “Aléa moral, subprimes, intérêt, taux, bulle…” sont autant de mots barbares qui reviennent sans cesse dans le film. Pour rendre accessible ce monde complexe, il a imaginé une trame narrative simple et captivante. Il a mis en scène un jeune trader qui tente d'alerter le monde au sujet des dangers irréversibles de la spéculation financière. Dans le même temps, il cherche à venger la mort de son mentor, ruiné et poussé au suicide. L'une des remarques importantes que l'on puisse souligner est l'omniprésence des écrans, télévision et ordinateurs compris, quasiment propulsés au rang de personnages. Une présence qui permet la dénonciation de la sainte alliance entre le monde de la communication et celui de la finance qui rend le monde réduit à des bulles éphémères, davantage fragile et instable. Certains ont reproché au film sa fin quelque peu heureuse à la manière d'un conte. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Howard's Comedy "Gung Ho” Isn't Funny

iviovit; Keview Howard's comedy "Gung Ho” isn’t funny lue of the individual. It never Too many of the gags are easily actor behaves like an idiot most By Matt Diedrich really gets any more compli predictable, based on Japanese of the time doesn’t help matters Reporter cated than that, or any more in stereotypes, or just not funny. either. teresting. Gedde Watanabe, who ap The viewer does find himself peared in “Sixteen Candles” and becoming more involved in the To make matters worse, the “Volunteers,” achieves some With the back-to-back suc movie’s second half, mainly be writers insist upon giving Kea success as the leader of the cesses of “Splash” and “Co cause the filmmakers decide to ton an endless string of “rous management team. His charac coon” under his belt, director ter is certainly more believable Ron Howard is starting to look and more likable than Keaton’s, like the next Steven Spielberg. and he frequently steals scenes Like Spielberg, he has received Whenever Keaton tries to crack a joke, the from his co-star. high praise for his ability to Japanese respond with blank, unamused make hit movies that display a iWimi Rogers gives an unim lot of heart. stares. Unfortunately, the audience will Yet even Spielberg had his likely react the same way. pressive non-performance as “1941,” and now Howard con Keaton’s girlfriend, in a role tinues the tradition with his which requires her to dump new movie “Gung Ho,” a lame him when he’s a jerk and take comedy that simply isn’t funny. -

Reading for Fictional Worlds in Literature and Film

Reading for Fictional Worlds in Literature and Film Danielle Simard Doctor of Philosophy University of York English and Related Literature March, 2020 2 Abstract The aim of this thesis is to establish a critical methodology which reads for fictional worlds in literature and film. Close readings of literary and cinematic texts are presented in support of the proposition that the fictional world is, and arguably should be, central to the critical process. These readings demonstrate how fictional world-centric readings challenge the conclusions generated by approaches which prioritise the author, the reader and the viewer. I establish a definition of independent fictional worlds, and show how characters rather than narrative are the means by which readers access the fictional world in order to analyse it. This interdisciplinary project engages predominantly with theoretical and critical work on literature and film to consider four distinct groups of contemporary novels and films. These texts demand readings that pose potential problems for my approach, and therefore test the scope and viability of my thesis. I evaluate character and narrative through Fight Club (novel, Chuck Palahniuk [1996] film, David Fincher [1999]); genre, context, and intertextuality in Solaris (novel, Stanisław Lem [1961] film, Andrei Tarkovsky [1974] film, Steven Soderbergh [2002]); mythic thinking and character’s authority with American Gods (novel, Neil Gaiman [2001]) and Anansi Boys (novel, Neil Gaiman [2005]); and temporality and nationality in Cronos (film, Guillermo -

Film Streams Programming Calendar Westerns

Film Streams Programming Calendar The Ruth Sokolof Theater . July – September 2009 v3.1 Urban Cowboy 1980 Copyright: Paramount Pictures/Photofest Westerns July 3 – August 27, 2009 Rio Bravo 1959 The Naked Spur 1953 Red River 1948 Pat Garrett & High Noon 1952 Billy the Kid 1973 Shane 1953 McCabe and Mrs. Miller 1971 The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance 1962 Unforgiven 1992 The Magnificent Seven 1960 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward The Good, the Bad Robert Ford 2007 and the Ugly 1966 Johnny Guitar 1954 There’s no movie genre more patently “American” True Westerns —the visually breathtaking work of genre auteurs like Howard than the Western, and perhaps none more Hawks, John Ford, Sam Peckinpah, and Sergio Leone—are more like Greek generally misunderstood. Squeaky-clean heroes mythology set to an open range, where the difference between “good” and versus categorical evil-doers? Not so much. “bad” is often slim and sometimes none. If we’re missing one of your favorites here, rest assured this is a first installment of an ongoing salute to this most epic of all genres: the Western. See reverse side for full calendar of films and dates. Debra Winger August 28 – October 1, 2009 A Dangerous Woman 1993 Cannery Row 1982 The Sheltering Sky 1990 Shadowlands 1993 Terms of Endearment 1983 Big Bad Love 2001 Urban Cowboy 1980 Mike’s Murder 1984 Copyright: Paramount Pictures/Photofest From her stunning breakthrough in 1980’s URBAN nominations to her credit. We are incredibly honored to have her as our COWBOY to her critically acclaimed performance special guest for Feature 2009 (more details on the reverse side), and for in 2008’s RACHEL GETTING MARRIED, Debra her help in curating this special repertory series featuring eight of her own Winger is widely regarded as one of the finest films—including TERMS OF ENDEARMENT, the Oscar-winning picture actresses in contemporary cinema, with more that first brought her to Nebraska a quarter century ago. -

The Cinema of Oliver Stone

Conclusion Although we are clearly overreaching, it’s too easy to talk about the USA losing its grip because we happen to be rooting for another approach. It’s not going to go away that easily. This empire is Star Wars in the ‘evil empire’ sense of the words … We are virtually becoming a tyranny against the rest of the world. It’s not evident to people at home, because they don’t see the consensus in the media and they don’t see the harm the USA does abroad. We are not in decline. We are decayed and corrupt and immoral, but not in decline. The USA exerts its will in Europe, Asia, much of the Middle East, and still much of Latin America. The recent revela- tions that the NSA’s and the UK’s surveillance programmes are linked is big news.1 Oliver Stone has been a fixture in the Hollywood landscape since his Oscar- winning script for Midnight Express (Alan Parker, 1978). That high-profile foothold gave him the opportunity to build slowly towards his ambition of capturing on film what he had lived through in Vietnam during 1967 and 1968. The young Yale man who had entered the army was a cerebral romantic in search of adventure; but his experience, not just of combat but also of his return to a country that was already openly divided about the war, altered his perspective and the direction of his life. Enrolment at film school under the GI Bill seemed to offer a way of expressing his anger and disillusionment, and the same determination that had kept him alive in South-East Asia now drove him on to try and tell something of that experience on film. -

Greatest Year with 476 Films Released, and Many of Them Classics, 1939 Is Often Considered the Pinnacle of Hollywood Filmmaking

The Greatest Year With 476 films released, and many of them classics, 1939 is often considered the pinnacle of Hollywood filmmaking. To celebrate that year’s 75th anniversary, we look back at directors creating some of the high points—from Mounument Valley to Kansas. OVER THE RAINBOW: (opposite) Victor Fleming (holding Toto), Judy Garland and producer Mervyn LeRoy on The Wizard of Oz Munchkinland set on the MGM lot. Fleming was held in high regard by the munchkins because he never raised his voice to them; (above) Annie the elephant shakes a rope bridge as Cary Grant and Sam Jaffe try to cross in George Stevens’ Gunga Din. Filmed in Lone Pine, Calif., the bridge was just eight feet off the ground; a matte painting created the chasm. 54 dga quarterly photos: (Left) AMpAs; (Right) WARneR BRos./eveRett dga quarterly 55 ON THEIR OWN: George Cukor’s reputation as a “woman’s director” was promoted SWEPT AWAY: Victor Fleming (bottom center) directs the scene from Gone s A by MGM after he directed The Women with (left to right) Joan Fontaine, Norma p with the Wind in which Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh) ascends the staircase at Shearer, Mary Boland and Paulette Goddard. The studio made sure there was not a Twelve Oaks and Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) sees her for the first time. The set single male character in the film, including the extras and the animals. was built on stage 16 at Selznick International Studios in Culver City. ight) AM R M ection; (Botto LL o c ett R ve e eft) L M ection; (Botto LL o c BAL o k M/ g znick/M L e s s A p WAR TIME: William Dieterle (right) directing Juarez, starring Paul Muni (center) CROSS COUNTRY: Cecil B.