Going Native in Sicily Christy Canterbury / December 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Cellar List

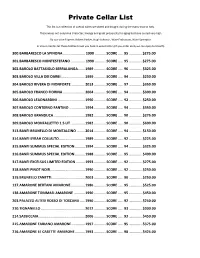

Private Cellar List This list is a collection of special wines we tasted and bought during the many trips to Italy. These wines not only have character, lineage and great propensity for aging but have scored very high By our wine Experts: Robert Parker, Hugh Johnson, Wine Enthusiast, Wine Spectator In Vinum Veritas let these bottles travel you back in wine history (if you order early we can open to breath) 300.BARBARESCO LA SPINONA ..................... 1990 ...........SCORE ..... 95 ............. $275.00 301.BARBARESCO MONTESTEFANO .............. 1990 ...........SCORE ..... 95 ............. $275.00 302.BAROLO BATTASIOLO SERRALUNGA .......1989 ............SCORE ..... 96 ............. $325.00 303.BAROLO VILLA DEI DARBI .......................1999 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $250.00 304.BAROLO RIVERA DI MONFORTE .............2013 ............SCORE ..... 97 ............. $350.00 305.BAROLO FRANCO FIORINA .....................2004 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $300.00 306.BAROLO LEAONARDINI ..........................1990 ............SCORE ..... 92 ............. $250.00 307.BAROLO CONTERNO FANTINO ...............1994 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $350.00 308.BAROLO GRANDUCA ..............................1982 ............SCORE ..... 90 ............. $275.00 309.BAROLO MONFALLETTO 1.5 LIT. .............1982 ............SCORE ..... 90 ............. $600.00 313.BANFI BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO ........2014 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $150.00 314.BANFI SYRAH COLLALTO .........................1989 ............SCORE -

An Investigation Into the Attitudes of UK Independent Wine Merchants Towards the Wines of Sardinia

An investigation into the attitudes of UK independent wine merchants towards the wines of Sardinia. © The Institute of Masters of Wine 2016. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission. This publication was produced for private purpose and its accuracy and completeness is not guaranteed by the Institute. It is not intended to be relied on by third parties and the Institute accepts no liability in relation to its use. CONTENTS 1. ABSTRACT 1 2. INTRODUCTION 2 3. RESEARCH CONTEXT AND LITERATURE REVIEW 4 3.1: UK Independent Shops 4 3.2: UK Wine Market 5 3.3: UK Independent Wine Merchants 5 3.4: Wines of Sardinia 7 3.5: Wines of Sardinia in the UK market 8 3.6: Surveys of IWMs 9 3.7: UK consumer studies 9 3.8: Retailer and consumer attitudes 10 4. METHODOLOGY 11 4.1: Overview 11 4.2: Definition of IWMs and Population 11 4.3: Sample Selection 12 4.4: Interviews 12 4.5: Survey Design 13 4.6: Survey Implementation 15 4.7: Analysis 15 5. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS 16 5.1: Overview 16 5.2: Response Rate 16 5.3: The Respondents 17 5.3.1: Specialisation 18 5.3.2: Listings 19 5.3.3: Factors in selling Sardinian Wine 22 5.4: Understanding of Sardinian Wine 25 5.4.1: Engagement 25 5.4.2: Knowledge 26 5.5: Attitudes towards Sardinian Wine 28 5.5.1: Price and Value 30 5.5.2: Grape Varieties 32 5.5.3: Brands 34 5.5.4: Packaging 34 5.5.5: Style 35 5.5.6: Sicily 35 5.6: Other Observations 36 6. -

Moscato Cerletti, a Rediscovered Aromatic Cultivar with Oenological Potential in Warm and Dry Areas

Received: 27 January 2021 y Accepted: 2 July 2021 y Published: 29 July 2021 DOI:10.20870/oeno-one.2021.55.3.4605 Moscato Cerletti, a rediscovered aromatic cultivar with oenological potential in warm and dry areas Antonio Sparacio1, Francesco Mercati2, Filippo Sciara1,3, Antonino Pisciotta3, Felice Capraro1, Salvatore Sparla1, Loredana Abbate2, Antonio Mauceri4, Diego Planeta3, Onofrio Corona3, Manna Crespan5, Francesco Sunseri4* and Maria Gabriella Barbagallo3* 1 Istituto Regionale del Vino e dell’Olio, Via Libertà 66 – I-90129 Palermo, Italy 2 CNR - National Research Council of Italy - Institute of Biosciences and Bioresources (IBBR) - Corso Calatafimi 414, I-90129 Palermo, Italy 3 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, Università degli Studi di Palermo, Viale delle Scienze 11 ed. H, I-90128 Palermo, Italy 4 Department AGRARIA - Università Mediterranea of Reggio Calabria - Feo di Vito, I-89124 Reggio Calabria, Italy 5 CREA - Centro di ricerca per la viticoltura e l’enologia – Viale XXVIII Aprile 26, Conegliano (Treviso), Italy *corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] Associate editor: Laurent Jean-Marie Torregrosa ABSTRACT Baron Antonio Mendola was devoted to the study of grapevine, applying ampelography and dabbling in crosses between cultivars in order to select new ones, of which Moscato Cerletti, obtained in 1869, was the most interesting. Grillo, one of the most important white cultivars in Sicily, was ascertained to be an offspring of Catarratto Comune and Zibibbo, the same parents which Mendola claimed he used to obtain Moscato Cerletti. Thus the hypothesis of synonymy between Moscato Cerletti and Grillo or the same parentage for both sets of parents needs to be verified. -

WHITE WINE Grillo Terre Siciliane 2016 Angelo 10 Favorita 2015

WHITE WINE by the glass RED WINE by the glass Grillo Terre Siciliane 2016 Angelo 10 Chianti Classico Castelgreve 2014 Castelli del Grepevesa 10 Favorita 2015 Ressia Langhe 12 Nero D’Avola 2016 Angelo 10 Chardonnay Tellus 2015 Falesco 12 Sangiovese Podere del Giuggiolo 2014 Carte alla Flora 11 Spumante Sorrentino Dore 14 Rosso di Toscana 2010 Clemente VII 14 Rosato Toscano 2017 Istine 15 Monferrato Rosso Il Baciale 2015 Braida 15 Pinot Grigio 2015 Collio Schiopetto 15 Pinot Nero 2015 Masut Da Rive 18 Gavi di Gavi 2016 Broglia La Meirana 15 Supertuscan 2015 Il Bruciato Bolgheri 19 Pecorino 2016 Ciavolich 15 Barbaresco Riserva 2011 Terre del Barolo 22 PRESTIGIOUS WHITE WINE by the glass 2 oz 4 oz 6 oz PRESTIGIOUS RED WINE by the glass 2 oz 4 oz 6 oz Ribolla/Verduzzo/Picolit 2014 Ronchi di Cialla 7 14 21 Brunello di Montalcino 2012 La Magia 10 20 30 Chardonnay 2014 Valcanzjria 9 18 27 Barolo 2010 Deltetto 15 30 45 WHITE WINE by the bottle RED WINE by the bottle Grillo Terre Siciliane 2016 Angelo 40 Nero D’Avola 2016 Angelo 40 Vermentino Lugore 2016 Sardus Pater 40 Chianti Classico Castelgreve 2014 Castelli del Grepevesa 40 Favorita 2015 Ressia Langhe 45 Sangiovese Podere del Giuggiolo 2014 Corte alla Flora 44 Spumante Sorrentino Dore 46 Rosso Di Toscana 2010 Clemente VII 54 Chardonnay Tellus 2015 Falesco 48 Nebbiolo D’Alba 2015 Selle 60 Rosato Toscano 2017 Istine 55 Monferrato Rosso Il Baciale 2015 Braida 60 Vermentino Dueluglio 2015 La Corsa 56 Rosso di Montalcino 2015 La Fornace 60 Greco di Tufo Oro 2015 De Concilis 56 Pinot Nero 2015 Masut -

Picolit D.O.C

PICOLIT D.O.C. COLLI ORIENTALI DEL FRIULI − Controlled and Guaranteed Designation of Origin Sweet white wine prized of a straw yellow, delicate scent reminiscent of honey and wildflowers, taste warm, harmonious, sweet with a pleasantly bitter aftertaste. GRAPES: 100% Picolit VINE: Indigenous variety from Friuli, undoubtedly ancient, already cultivated in the Roman imperial period, had the honor to delight the palates of popes and emperors. Among the admirers of Picolit, it also includes Carlo Gol doni, who defines this wine the brightest gem of Friuli wine. Vine arrived today thanks to the work of Count Fabio Asquini of Fagagna who in 1700 saved this precious vine f rom certain death. It was the same Asquini that made him known to the "foreigners" in high−prestige markets su ch as London, Paris, Genoa, Milan, Ancona. The Picolit was appreciated and consumed not only in Italy, but he found among his great admirers even the Court of France, the Papal Court and even the King of Sardinia, the E mperor of Austria and the Czar of Russia. The Picolit is characterized by very limited production due to a peculiarity in the development of the grapes that undergo a partial floral abortion, leaving the loose bunch with smaller and sweeter grapes. Today it is cultivated in the hills of Friuli Venezia Giulia, in the provinces of Udine and Gorizia. The 2006 vintage is the first as Denomi nation of controlled and guaranteed origin and thanks to his particular value, Picolit is the second denomination of controlled and guaranteed origin of the whole Friuli Venezia Giulia. -

Sparkling Wine White Wine Sommelier's Cellar Picks

Sommelier's Cellar Picks Listed below are bottles from outside the borders of Italy. These selections were curated by our sommelier to enhance your meal at Tavola. The following opportunities highlight some of the best kept secrets on our Cloister list. Bin Vintage White and Sparkling Glass Price Format 879 Brut, Charles Heidsieck, Reserve, Champagne, France 30 150 c1566 2018 Sauvignon Blend, Picque Caillou, Pessac-Leognan, Bordeaux 90 Chardonnay, Vincent Girardin, Burgundy 20 80 c1961 2017 Chardonnay, Jouard, Les Vides Bourses, Premier Cru, Burgundy 294 Red c2940 2017 Pinot Noir, Ceritas, Elliott Vineyard, Sonoma Coast, California 164 3197 Pinot Noir, Pascale Matrot, Burgundy 20 80 c3261 2017 Pinot Noir, Tollot-Beaut, Beaune-Greves, Premier Cru, Burgundy 230 c5271 2008 Tempranillo, Lopez de Heredia, Vina Tondonia , Rioja, Reserva 135 c7139 2015 Cabernet Blend, Lions de Batailley, Pauillac, Bordeaux 158 Italy Sparkling Wine 95 Metodo Classico Brut Rose, Ferrari, Trento 18 36 375mL 973 Metodo Classico Brut, Ca' del Bosco, Franciacorta 25 125 Prosecco, Maschio dei Cavalieri, Valdobbiadene, Veneto 14.5 72.5 White Wine Trentino-Alto Adige 1314 2017 Kerner, Abbazia di Novacella 65 1408 Sauvignon Blanc, Andrian, Floreado 17 68 1254 2019 Pinot Grigio, Terlan 60 c1848 2018 Chardonnay Blend, Elena Walch, Beyond the Clouds 168 Piemonte 1316 2018 Arneis, Vietti 67 1850 2014 Chardonnay, Gaja, Gaia & Rey , Langhe 615 1845 2016 Chardonnay, Aldo Conterno, Bussiador , Langhe 180 1290 2017 Sauvignon Blanc, Marchesi di Gresy, Langhe 72 White Wine Friuli-Venezia -

Poggio Anima 'Uriel' Grillo

POGGIO ANIMA poggioanima.com Poggio Anima ‘Uriel’ Grillo Sicily - Italy 2017 A collaboration between famed Brunello di Montalcino producer Riccardo Campinoti and his importer from Vine Street Imports, Ronnie Sanders, whose wines attract as much attention for what's on the label as what's in the bottle. Poggio Anima is designed to over-deliver for its modest price point. Uriel, the archangel of repentance. Uriel played a very important role in ancient texts as the rescuer of Jesus' cousin John the Baptist from the Massacre of the Innocents ordered by King Herod. The translation of Uriel is ‘God of Light.’ Uriel was the angel who checked each of the doors during the Passover in order to ensure safety for God’s people. Grillo is a very resilient grape and one that withstands a lot of heat and wind on Sicily. It is probably best known as the foundation for Marsala but in its ‘dry’ form has many interesting characteristics. It is the most important white grape on Sicily and therefore the ‘principal light.’ Grillo, also known as Riddu, is a white wine grape variety which withstands high temperatures and is widely used in Sicilian wine-making and, in particular, for Marsala. Grillo is crisp and light in texture, with moderate acidity and notable sweetness. 2017 was one of the hottest vintages on record and yet commenced with some of the nastiest frosts that the island, and mainland, have ever seen; the Ice Maiden and Lucifer as it has been referred! It is well-known that 2017 marked the smallest harvest in Italy in more than 60 years, thankfully the hillside plantings higher up the hill at this vineyard saved the yields during the frost but when the heat came, and boy did it, with temperatures routinely topping 40°C (104°F). -

By the Glass

BY THE GLASS WHITE WINES 2017 Chardonnay Benziger, Carneros, California 9/36 2017 Viognier-Roussanne Blend, Jean-Luc Colombo, Côtes du Rhône 10/40 2017 Pinot Grigio Benvolio, Friuli, Italy 9/36 2017 Riesling Dr. Loosen, Mosel, Germany 8/32 2017 Semillon Blend Château Graville-Lacoste, Bordeaux 10/40 2018 Sauvignon Blanc Babich, Marlbrough, New Zealand 10/40 2016 Pinot Blanc Gustave Lorentz, Alsace, France 9/36 2018 Moscato Piquitos, Valencia, Spain 8/32 N/V Vinho Verde Octave, Portugal 8/32 ROSÉ 2018 Bonny Doon, Vin Gris de Cigare, Central Coast 10/40 RED WINES 2018 Cabernet Sauvignon McManis, California 8/32 2017 Cabernet Sauvignon Quilt, Napa 15/60 2016 Cabernet Sauvignon Pine Ridge Vineyards 25/100 2017 Zinfandel 1000 Stories Medocino, California 10/40 2016 Malbec Catena Vista Flores, Mendoza, Argentina 10/40 2017 Sangiovese Blend Remole Frescobaldi Toscana 8/32 2015 Merlot Rodney Strong, Sonoma County 10/40 2016 Pinot Noir Migration, Sonoma Coast 13/52 2014 Bordeaux Blend Château Loudenne, Médoc, France 15/60 2016 Chinon Château du Coudray Montpensier, France 11/44 2016 Shiraz Barossa Ink, Australia 10/40 2017 Vinho Tinto Casa Ferrerinha, Papa Figus Douro Portugal 10/40 SPARKLING WINES & CHAMPAGNE M/V Mionetto Prosecco, Treviso DOC 10/40 M/V Moet & Chandon Imperial, à Epernay AOC 25 WINE FLIGHTS Enjoy three glasses of wine, 3 oz each, or have us pair a wine with each course 16 1 CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING WINES SPARKLING 2008 Gramona Grand Cuvee, Sant Sadurni D’Anoia 45 M/V Kenwood Cuvee Brut 28 M/V Roederer Estate Brut, Anderson Valley, California 60 2010 Taltarni Taché, South Eastern Australia 45 M/V Steorra Brut, Russian River, Sonoma, California 50 M/V Toso Brut Mendoza 35 FRANCE- BRUT VINTAGE CHAMPAGNE 2008 Cuvée Dom Perignon AOC, à Eperry 300 2008 Louis Roederer Cristal 450 BRUT MULTIPLE VINTAGE CHAMPAGNE M/V Tattinger La Francaise AOC, Reims 120 M/V Veuve Clicquot, Ponsardin AOC, Reims 120 M/V Perrier-Jouët, Blason Rosé, Eperney 175 M/V G.H. -

2018-Donnafugata-Digital-Brochure

gambina Donnafugata is a ©fabio family business now at the 5th generation The name The name Donnafugata refers to the novel by Tomasi di Lampedusa entitled Il Gattopardo (The Leopard). A name that means “donna in fuga” (woman in flight) and refers to the story of a queen who found refuge in the part of Sicily where the company’s vineyards are located today. An adventure that inspired the corporate logo: the image of a woman’s head with windblown hair that dominates every bottle. II 1 Antonio Rallo, president of Consorzio DOC Sicilia, was Timeline 2016 Donnafugata also head of Unione Italiana Vini. Presentation of the debut wines under vigneti e cantine in 5 territori 2018 1995 the Etna DOC The family’s gambina denominations historic winery (1851): ©fabio (steel, cement or wood) and bottling. The first vintage of Mille e Una 1995 The Rallo family Notte conceived Giacomo Rallo, 1851 entered the wine by Giacomo Rallo pioneer of the 15 hectares (37 acres) world in Sicily in together with the Donnafugata Music & Wine worldwide in production in 5 districts the wake of English great enologist with José Rallo singing at success of Sicily, ageing White grapes: Carricante entrepreneurs. Giacomo Tachis. 2005 the Blue Note in New York. passed away. Red grapes: Nerello Mascalese Winery: Randazzo Giacomo and Donnafugata started The first Creation of Gabriella operating on the nighttime harvest experimental 1983 1989 1998 2017 created island of Pantelleria of Chardonnay at fields in Donnafugata, where it cultivated Contessa Entellina. 2009/10 Contessa a name bush-trained Zibibbo A way to Entellina and with artistic vines on terraces and preserve the Pantelleria for connections. -

New Wine List

Sparkling by the glass Glass 125ml 1 Prosecco di Vallate DOC Vallate £ 7.60 2 Veuve de cliquot Champagne £ 17.50 White wines by the glass Glass Carafe 175ml 250ml 3 Le Pianure bianco, Andrea stocco £ 7.00 £ 9.00 4 Grillo "kore" Colomba Bianca £ 8.50 £ 11.00 5 Verdicchio dei castelli di jesi "San Lorenzo" £ 12.50 £ 16.60 Rose' wines by the glass 6 Remole rosato, Frescobaldi £ 9.00 £ 12.00 Red wines by the glass glass Carafe 175ml 250ml 7 Merlot Victoria,Castellargo £ 7.00 £ 9.00 8 Aglianico Trigaio £ 8.50 £ 11.50 9 Chianti Classico Banfi £ 14.00 £ 18.00 Prosecco and Champagne 10 Prosecco "Extra Dry" DOC, Vallate £ 38.00 Glera grapes, Clean, fresh and elegant, with delicate, persistent bubbles 11 Champagne Rosé 1er Cru, Marc Hebrart £ 64.00 80% Pinot noir, 20% Chardonnay grapes "Light salmon rosé colour. 12 Veuve de Clicquot £ 105.00 50 to 55% Pinot Noir,15 to 20% Pinot Meunier and 28 to 33% Chardonnay from the area of "Montagne de Reims". Rose' wine 13 Rémole Rosato IGT, Frescobaldi £ 37.00 Merlot Grapes. Delicate, lively and fruity with fresh and fragrant taste. White wines Toscana 14 Remole bianco IGT, Frescobaldi £ 30.00 50% Trebbiano and 50% Vermentino grapes 15 Chardonnay, Le Rime, Banfi £ 41.00 Chardonnay and Pinot Grigio grapes Piemonte 16 Gavi di Gavi collina Serragrilli DOCG £ 51.00 100% Cortese grapes. A delicious, lively and citrusy nose is matched Valle D'Aosta 17 Chardonnay "Cuvee Frissoniere" DOC, Les Cretes £ 63.00 100% Chardonnay grapes. The wine shows a brilliant straw yellow Friuli Venezia Giulia 18 Sauvignon Blanc DOC, Ronco delle Betulle £ 48.00 100% Sauvignon blanc grapes. -

Winter Cocktails $16

DRINKS WINTER COCKTAILS $16 NON CLASSICO SPRITZ Contratto Aperitif, Grey Goose, Grapefruit, St. Germain, Prosecco SICILIAN SOL Caffo Amaretto, Avua Amburana Cachaça, lemon, Angostura bitter, Prosecco L’AMICO NEGRONI Fords Gin, Carpano Antica & Cocchi Americano Vermouths, Cappelletti bitter UN FIZZ ITALIANO Montenegro Amaro, lemon, lime, Prosecco BROOKLYN BOUND Rittenhouse Rye, Carpano Punt e Mes, Ramazzotti Amaro, Star Anise infused Luxardo Maraschino MIELLISSIMO Plymouth Gin, Marolo Camomile Grappa, lemon, honey, egg white & Absinthe PRIMO UOMO La Diablada Pisco, Dolin Blanc, lime, blood orange, sage BOTTLED BEER HOFBRÄU ORIGINAL LAGER, Germany 10 BODDINGTON’S PUB ALE, England 10 SCHNEIDER WEISEN EDEL-WEISS, Germany 12 GUN HILL ROLL CALL 3 IPA, Bronx 12 FOLLINA GIANNA DOUBLE MALT, Italy 12 EVIL TWIN/TWO ROADS PACHAMAMA PORTER, CT 12 OMNIPOLLO ANIARA PALE ALE W/ LEMON, Sweden 22 GIGANTIC ‘KISS THE GOAT’ DOPPLEBOCK, Oregon 25 PARADOX SKULLY #40 SOUR, Colorado 35 BRUERY ‘CONFESSION’ SOUR BLONDE ALE, California 50 DESCENDANT POM POMME SPARKLING CIDER, Queens 30 EVE’S CIDERY PERRY PEAR SPARKLING CIDER, Finger Lakes 30 Consumption of raw or undercooked eggs may increase risk of food borne illness WINE BY GLASS SPARKLING PROSECCO FANTINEL Veneto, NV | 12 LAMBRUSCO ‘AMABILE’ CLETO CHIARLI Emilia-Romagna, 2014 | 12 FRANCIACORTA LANTIERI EXTRA BRUT Lombardy, NV | 16 WHITE LANGHE ARNEIS MONTEZEMOLO Piedmont, 2014 | 14 PINOT GRIGIO ‘I VIGNETTI’ PETER SOLVA Trentino-Alto Adige, 2013 | 15 SYLVANER PACHERHOF Trentino-Alto Adige, 2014 | 17 MÜLLER-THURGAU -

Evaluation of Winegrape Varieties for Warm Climate Regions San

Evaluation of Winegrape Varieties for Warm Climate Regions San Joaquin Valley Viticulture Technical Group Jan 11, 2012 James A. Wolpert Extension Viticulturist Department of Viticulture and Enology UC Davis Factors affecting selection of varieties Your location – Cool vs. warm vs. hot – Highly regarded vs. less well known appellation The Marketplace – Supply and demand – Mainstream vs. niche markets Talk Outline • California Variety Status • Variety Trial Data From Warm Region • World Winegrape Variety Opportunities Sources of Variety Information in California California Grape Acreage – http://www.nass.usda.gov/ca/ Grape Crush Report – http://www.nass.usda.gov/ca/ Gomberg-Fredrikson Report – http://www.gfawine.com/ Market Update Newsletter (Turrentine Wine Brokerage) – http://www.turrentinebrokerage.com/ Unified Symposium (late January annually) – http://www.unifiedsymposium.org/ U.S. Wines • 10 varieties comprise about 80% of all bottled varietal wine: – Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Zinfandel (incl White Zin), Sauvignon blanc, Pinot noir, Pinot gris/grigio, Syrah/Shiraz, Petite Sirah, Viognier • First three are often referred to as the “International Varieties” New Varieties: Is There a Role? • Interest in “New Varieties” – Consumer interest – excitement of discovery of new varieties/regions • Core consumers say ABC: “Anything but Chardonnay” – Winemaker interest • Capture new consumers • Offer something unique to Club members • Blend new varieties with traditional varieties to add richness and interest: flavor, color,