Effects on Varietal Aromas During Wine Making: a Review of the Impact of Varietal 1 2 Aromas on the Flavor of Wine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discrimination of Brazilian Red Varietal Wines According to Their Sensory

1172 DISCRIMINATION OFMIELE, BRAZILIAN A. & RIZZON, REDL. A. VARIETAL WINES ACCORDING TO THEIR SENSORY DESCRIPTORS Discriminação de vinhos tintos Brasileiros varietais de acordo com suas características sensoriais Alberto Miele1, Luiz Antenor Rizzon2 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper was to establish the sensory characteristics of wines made from old and newly introduced red grape varieties. To attain this objective, 16 Brazilian red varietal wines were evaluated by a sensory panel of enologists who assessed wines according to their aroma and flavor descriptors. A 90 mm unstructured scale was used to quantify the intensity of 26 descriptors, which were analyzed by means of the Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The PCA showed that three important components represented 74.11% of the total variation. PC 1 discriminated Tempranillo, Marselan and Ruby Cabernet wines, with Tempranillo being characterized by its equilibrium, quality, harmony, persistence and body, as well as by, fruity, spicy and oaky characters. The other two varietals were defined by vegetal, oaky and salty characteristics; PC 2 discriminated Pinot Noir, Sangiovese, Cabernet Sauvignon and Arinarnoa, where Pinot Noir was characterized by its floral flavor; PC 3 discriminated only Malbec, which had weak, floral and fruity characteristics. The other varietal wines did not show important discriminating effects. Index terms: Sensory analysis, enology, Vitis vinifera. RESUMO Conduziu-se este trabalho, com o objetivo de determinar as características sensoriais de vinhos tintos brasileiros elaborados com cultivares de uva introduzidos no país há algum tempo e outros, mais recentemente. Para tanto, as características de 16 vinhos tintos varietais brasileiros foram determinadas por um painel formado por enólogos que avaliaram os vinhos de acordo com suas características de aroma e sabor. -

WINE YEAST: the CHALLENGE of LOW TEMPERATURE Zoel Salvadó Belart Dipòsit Legal: T.1304-2013

WINE YEAST: THE CHALLENGE OF LOW TEMPERATURE Zoel Salvadó Belart Dipòsit Legal: T.1304-2013 ADVERTIMENT. L'accés als continguts d'aquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials d'investigació i docència en els termes establerts a l'art. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix l'autorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No s'autoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes d'explotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des d'un lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc s'autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Investigation of Bacteria Associated with Australian Wine Grapes Using Cultural and Molecular Methods

Investigation of bacteria associated with Australian wine grapes using cultural and molecular methods Sung Sook Bae A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales Food Science and Technology School of Chemical Engineering and Industrial Chemistry Sydney, Australia 2005 i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of materials which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other education institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Sung Sook Bae ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to numerous individuals who have contributed to the completion of this work, and I wish to thank them for their contribution. Firstly and foremost, my sincere appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Graham Fleet. He has given me his time, expertise, constant guidance and inspiration throughout my study. I also would like to thank my co-supervisor, Dr. Gillian Heard for her moral support and words of encouragement. I am very grateful to the Australian Grape and Wine Research Development and Corporation (GWRDC) for providing funds for this research. -

New Zealand Wine Fair Sa N Francisco 2013 New Zealand Wine Fair Sa N Francisco / May 16 2013

New Zealand Wine Fair SA N FRANCISCO 2013 New Zealand Wine Fair SA N FRANCISCO / MAY 16 2013 CONTENTS 2 New Zealand Wine Regions New Zealand Winegrowers is delighted to welcome you to 3 New Zealand Wine – A Land Like No Other the New Zealand Wine Fair: San Francisco 2013. 4 What Does ‘Sustainable’ Mean For New Zealand Wine? 5 Production & Export Overview The annual program of marketing and events is conducted 6 Key Varieties by New Zealand Winegrowers in New Zealand and export 7 Varietal & Regional Guide markets. PARTICIPATING WINERIES When you choose New Zealand wine, you can be confident 10 Allan Scott Family Winemakers you have selected a premium, quality product from a 11 Babich Wines beautiful, sophisticated, environmentally conscious land, 12 Coopers Creek Vineyard where the temperate maritime climate, regional diversity 13 Hunter’s Wines and innovative industry techniques encourage highly 14 Jules Taylor Wines distinctive wine styles, appropriate for any occasion. 15 Man O’ War Vineyards 16 Marisco Vineyards For further information on New Zealand wine and to find 17 Matahiwi Estate SEEKING DISTRIBUTION out about the latest developments in the New Zealand wine 18 Matua Valley Wines industry contact: 18 Mondillo Vineyards SEEKING DISTRIBUTION 19 Mt Beautiful Wines 20 Mt Difficulty Wines David Strada 20 Selaks Marketing Manager – USA 21 Mud House Wines Based in San Francisco 22 Nautilus Estate E: [email protected] 23 Pacific Prime Wines – USA (Carrick Wines, Forrest Wines, Lake Chalice Wines, Maimai Vineyards, Seifried Estate) Ranit Librach 24 Pernod Ricard New Zealand (Brancott Estate, Stoneleigh) Promotions Manager – USA 25 Rockburn Wines Based in New York 26 Runnymede Estate E: [email protected] 27 Sacred Hill Vineyards Ltd. -

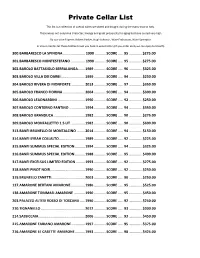

Private Cellar List

Private Cellar List This list is a collection of special wines we tasted and bought during the many trips to Italy. These wines not only have character, lineage and great propensity for aging but have scored very high By our wine Experts: Robert Parker, Hugh Johnson, Wine Enthusiast, Wine Spectator In Vinum Veritas let these bottles travel you back in wine history (if you order early we can open to breath) 300.BARBARESCO LA SPINONA ..................... 1990 ...........SCORE ..... 95 ............. $275.00 301.BARBARESCO MONTESTEFANO .............. 1990 ...........SCORE ..... 95 ............. $275.00 302.BAROLO BATTASIOLO SERRALUNGA .......1989 ............SCORE ..... 96 ............. $325.00 303.BAROLO VILLA DEI DARBI .......................1999 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $250.00 304.BAROLO RIVERA DI MONFORTE .............2013 ............SCORE ..... 97 ............. $350.00 305.BAROLO FRANCO FIORINA .....................2004 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $300.00 306.BAROLO LEAONARDINI ..........................1990 ............SCORE ..... 92 ............. $250.00 307.BAROLO CONTERNO FANTINO ...............1994 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $350.00 308.BAROLO GRANDUCA ..............................1982 ............SCORE ..... 90 ............. $275.00 309.BAROLO MONFALLETTO 1.5 LIT. .............1982 ............SCORE ..... 90 ............. $600.00 313.BANFI BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO ........2014 ............SCORE ..... 94 ............. $150.00 314.BANFI SYRAH COLLALTO .........................1989 ............SCORE -

Introducing California Wines

Chapter 1 Introducing California Wines In This Chapter ▶ The gamut of California’s wine production ▶ California wine’s international status ▶ Why the region is ideal for producing wines ▶ California’s colorful wine history ll 50 U.S. states make wine — mainly from grapes but in some Acases from berries, pineapple, or other fruits. Equality and democracy end there. California stands apart from the whole rest of the pack for the quantity of wine it produces, the international reputation of those wines, and the degree to which wine has per- meated the local culture. To say that in the U.S., wine is California wine is not a huge exaggeration. If you want to begin finding out about wine, the wines of California are a good place to start. If you’re already a wine lover, chances are that California’s wines still hold a few surprises worth discov- ering. To get you started, we paint the big picture of California wine in this chapter. Covering All the Bases in WineCOPYRIGHTED Production MATERIAL Wine, of course, is not just wine. The shades of quality, price, color, sweetness, dryness, and flavor among wines are so many that you can consider wine a whole world of beverages rather than a single product. Can a single U.S. state possibly embody this whole world of wine? California can and does. Whatever your notion of wine is — even if that changes with the seasons, the foods you’re preparing, or how much you like the people you’ll be dining with — California has that base covered. -

An Investigation Into the Attitudes of UK Independent Wine Merchants Towards the Wines of Sardinia

An investigation into the attitudes of UK independent wine merchants towards the wines of Sardinia. © The Institute of Masters of Wine 2016. No part of this publication may be reproduced without permission. This publication was produced for private purpose and its accuracy and completeness is not guaranteed by the Institute. It is not intended to be relied on by third parties and the Institute accepts no liability in relation to its use. CONTENTS 1. ABSTRACT 1 2. INTRODUCTION 2 3. RESEARCH CONTEXT AND LITERATURE REVIEW 4 3.1: UK Independent Shops 4 3.2: UK Wine Market 5 3.3: UK Independent Wine Merchants 5 3.4: Wines of Sardinia 7 3.5: Wines of Sardinia in the UK market 8 3.6: Surveys of IWMs 9 3.7: UK consumer studies 9 3.8: Retailer and consumer attitudes 10 4. METHODOLOGY 11 4.1: Overview 11 4.2: Definition of IWMs and Population 11 4.3: Sample Selection 12 4.4: Interviews 12 4.5: Survey Design 13 4.6: Survey Implementation 15 4.7: Analysis 15 5. RESULTS AND ANALYSIS 16 5.1: Overview 16 5.2: Response Rate 16 5.3: The Respondents 17 5.3.1: Specialisation 18 5.3.2: Listings 19 5.3.3: Factors in selling Sardinian Wine 22 5.4: Understanding of Sardinian Wine 25 5.4.1: Engagement 25 5.4.2: Knowledge 26 5.5: Attitudes towards Sardinian Wine 28 5.5.1: Price and Value 30 5.5.2: Grape Varieties 32 5.5.3: Brands 34 5.5.4: Packaging 34 5.5.5: Style 35 5.5.6: Sicily 35 5.6: Other Observations 36 6. -

Impact of High Sugar Content on Metabolism and Physiology of Indigenous Yeasts

IMPACT OF HIGH SUGAR CONTENT ON METABOLISM AND PHYSIOLOGY OF INDIGENOUS YEASTS Federico Tondini A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Agriculture, Food and Wine Faculty of Sciences The University of Adelaide July 2018 1 2 I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I acknowledge that copyright of published works contained within this thesis resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University’s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. I acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of an Australian Government Research TrainingProgram Scholarship. 3 Abstract This PhD project is part of an ARC Training Centre for Innovative Wine Production larger initiative to tackle the main challenges for the Australian wine industry. -

Moscato Cerletti, a Rediscovered Aromatic Cultivar with Oenological Potential in Warm and Dry Areas

Received: 27 January 2021 y Accepted: 2 July 2021 y Published: 29 July 2021 DOI:10.20870/oeno-one.2021.55.3.4605 Moscato Cerletti, a rediscovered aromatic cultivar with oenological potential in warm and dry areas Antonio Sparacio1, Francesco Mercati2, Filippo Sciara1,3, Antonino Pisciotta3, Felice Capraro1, Salvatore Sparla1, Loredana Abbate2, Antonio Mauceri4, Diego Planeta3, Onofrio Corona3, Manna Crespan5, Francesco Sunseri4* and Maria Gabriella Barbagallo3* 1 Istituto Regionale del Vino e dell’Olio, Via Libertà 66 – I-90129 Palermo, Italy 2 CNR - National Research Council of Italy - Institute of Biosciences and Bioresources (IBBR) - Corso Calatafimi 414, I-90129 Palermo, Italy 3 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, Università degli Studi di Palermo, Viale delle Scienze 11 ed. H, I-90128 Palermo, Italy 4 Department AGRARIA - Università Mediterranea of Reggio Calabria - Feo di Vito, I-89124 Reggio Calabria, Italy 5 CREA - Centro di ricerca per la viticoltura e l’enologia – Viale XXVIII Aprile 26, Conegliano (Treviso), Italy *corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] Associate editor: Laurent Jean-Marie Torregrosa ABSTRACT Baron Antonio Mendola was devoted to the study of grapevine, applying ampelography and dabbling in crosses between cultivars in order to select new ones, of which Moscato Cerletti, obtained in 1869, was the most interesting. Grillo, one of the most important white cultivars in Sicily, was ascertained to be an offspring of Catarratto Comune and Zibibbo, the same parents which Mendola claimed he used to obtain Moscato Cerletti. Thus the hypothesis of synonymy between Moscato Cerletti and Grillo or the same parentage for both sets of parents needs to be verified. -

The Positive Effect of Aging in the Case of Wine

mathematics Article The Positive Effect of Aging in the Case of Wine Limor Dina Gonen 1,*, Tchai Tavor 2 and Uriel Spiegel 3,4 1 Department of Economics and Business Administration, Ariel University, Ariel 40700, Israel 2 Department of Economics and Management, The Max Stern Yezreel Valley College, Yezreel Valley 19300, Israel; [email protected] 3 Department of Management, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] 4 Zefat College, Zefat 1320611, Israel * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract: This paper examines the positive aspects of aging. Some items, such as valuable and rare stamps, old coins, works of art, and antiques, become more expensive over time. More popular examples demonstrating the positive effect of aging that influences price are the aging of boutique wine and artisan cheese. The present paper examines the wine aging process that brings about quality improvement. This process also leads to determining (i) optimal aging periods for different wines; (ii) optimal grape juice inventory allocations and prices for different wines; (iii) optimal quantities of different kinds of wine; and (iv) the time durations of wine production and consumption from each vintage. These aspects are considered in an environment in which the demand increases over time due to the aging and rarity of the product. Keywords: wine aging; production duration; consumption duration JEL Classification: D2; D21; D4; L12 1. Introduction Citation: Gonen, L.D.; Tavor, T.; The issue of optimal pricing and inventory policy for perishable products has been Spiegel, U. The Positive Effect of considered for decades. -

September 2000 Edition

D O C U M E N T A T I O N AUSTRIAN WINE SEPTEMBER 2000 EDITION AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD AT: WWW.AUSTRIAN.WINE.CO.AT DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition Foreword One of the most important responsibilities of the Austrian Wine Marketing Board is to clearly present current data concerning the wine industry. The present documentation contains not only all the currently available facts but also presents long-term developmental trends in special areas. In addition, we have compiled important background information in abbreviated form. At this point we would like to express our thanks to all the persons and authorities who have provided us with documents and personal information and thus have made an important contribution to the creation of this documentation. In particular, we have received energetic support from the men and women of the Federal Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management, the Austrian Central Statistical Office, the Chamber of Agriculture and the Economic Research Institute. This documentation was prepared by Andrea Magrutsch / Marketing Assistant Michael Thurner / Event Marketing Thomas Klinger / PR and Promotion Brigitte Pokorny / Marketing Germany Bertold Salomon / Manager 2 DOCUMENTATION Austrian Wine, September 2000 Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Austria – The Wine Country 1.1 Austria’s Wine-growing Areas and Regions 1.2 Grape Varieties in Austria 1.2.1 Breakdown by Area in Percentages 1.2.2 Grape Varieties – A Brief Description 1.2.3 Development of the Area under Cultivation 1.3 The Grape Varieties and Their Origins 1.4 The 1999 Vintage 1.5 Short Characterisation of the 1998-1960 Vintages 1.6 Assessment of the 1999-1990 Vintages 2. -

Dessert Wines 1

Dessert Wines 1 AMERICA 7269 Macari 2002 Block E, North Fork, Dessert Wines Long Island tenth 75.00 1158 Mayacamas 1984 Zinfandel Late Harvest 50.00 (2oz pour) 7218 Robert Mondavi 1998 Sauvignon Blanc 27029 Kendall-Jackson Late Harvest Chardonnay 7.50 Botrytis, Napa tenth 100.00 26685 Château Ste. Michelle Reisling 7257 Robert Mondavi 2014 Moscato D’Oro, Late Harvest Select 8.00 Napa 500ml 35.00 26792 Garagiste, ‘Harry’ Tupelo Honey Mead, 6926 Rosenblum Cellars Désirée Finished with Bern’s Coffee Blend 12.00 Chocolate Dessert Wine tenth 45.00 27328 Ferrari Carano Eldorado Noir Black Muscat 13.00 5194 Silverado Vineyards ‘Limited Reserve’ 26325 Dolce Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc Late Harvest 115.00 by Far Niente, Napa 19.00 7313 Steele 1997 ‘Select’ Chardonnay 27203 Joseph Phelps ‘Delice’ Scheurebe, St Helena 22.50 Late Harvest, Sangiacomo Vineyard tenth 65.00 6925 Tablas Creek 2007 Vin De Paille, Sacerouge, Paso Robles tenth 105.00 - Bottle - 7258 Ca’Togni 2009 Sweet Red Wine 7066 Beringer 1998 Nightingale, Napa tenth 65.00 by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 99.00 7289 Château M 1991 Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc 7090 Ca’Togni 2003 Sweet Red Wine by Monticello, Napa tenth 65.00 by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 150.00 6685 Château Ste. Michelle Reisling 7330 Ca’Togni 2001 Sweet Red Wine Late Harvest Select by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 150.00 7081 Château St. Jean 1988 Johannisberg Riesling, 6944 Ca’Togni 1999 Sweet Red Wine Late Harvest, Alexander Valley tenth 85.00 by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 105.00 7134 Ca’Togni 1995 Sweet Red Wine 6325 Dolce 2013 Semillon-Sauvignon Blanc by Philip Togni, Napa tenth 125.00 by Far Niente, Napa tenth 113.00 27328 Ferrari Carano Eldorado Noir Black Muscat 13.00 7000 Elk Cove Vineyard Ultima Riesling, 15.5% Residual Sugar, Willamette tenth 80.00 6777 Eroica 2000, Single Berry Select Riesling, by Chateau Ste.